National Vital

Statistics Reports

Volume 69, Number 2 January 30, 2020

This report was revised

on July 15, 2020, to

impute missing values

for race and Hispanic

origin for consistency

with other publications,

slightly changing

non-Hispanic maternal

deaths in Figure 2,

Tables D and 1, and

pages 1 and 5 text.

Maternal mortality is a high-profile health indicator used in

domestic and international settings (1–3). In the United States,

the National Center for Health Statistics’ (NCHS) National Vital

Statistics System (NVSS) is the source for official mortality

statistics, including those on maternal mortality. NCHS uses

the World Health Organization (WHO) definition for maternal

mortality: deaths of women while pregnant or within 42 days

of being pregnant, from any cause related to or aggravated by

the pregnancy or its management, but not from accidental or

incidental causes (i.e., neither caused nor complicated by the

woman being pregnant at the time of or within 1 year of death).

The classification of deaths involving pregnancy, childbirth and

puerperium specifically excludes external causes (i.e., accidents,

homicides, and suicides) as incidental. Late maternal deaths

(occurring between 43 days and 1 year of death) are also not

included as part of the WHO definition of maternal mortality.

NVSS has produced maternal mortality statistics for more

than a century based on causes of death reported on death

certificates. Over time, other data collection efforts emerged,

such as the Pregnancy Mortality Surveillance System in 1986,

and evidence demonstrated that the NVSS data underestimated

maternal mortality (4–9). To address the underreporting of

maternal deaths in vital statistics, a separate pregnancy checkbox

item was added to the U.S. Standard Certificate of Death in 2003;

see other reports that describe the checkbox implementation

in more detail (10,11). NCHS initially paused publication of

maternal mortality trends as states were transitioning to the

checkbox format. However, as implementation of the standard

checkbox took longer than expected, NCHS paused publication

of annual maternal mortality rates as well. As a result, NCHS has

not published an official estimate of the U.S. maternal mortality

rate since 2007. Now that all states have implemented a checkbox

as of the 2018 data year (noting that California implemented a

different checkbox from that on the U.S. Standard Certificate of

Death), NCHS is resuming publication of the maternal mortality

rate starting with 2018 data.

Maternal Mortality in the United States: Changes

in Coding, Publication, and Data Release, 2018

by Donna L. Hoyert, Ph.D., and Arialdi M. Miniño, M.P.H., Division of Vital Statistics

Abstract

This report describes changes in how the National Center for

Health Statistics (NCHS) will code, publish, and release maternal

mortality data and presents official 2018 maternal mortality

estimates using a new coding method. Due to the incremental

implementation of the pregnancy status checkbox item on the 2003

revised U.S. Standard Certificate of Death, NCHS last published

an official estimate of the U.S. maternal mortality rate in 2007.

As of 2018, implementation of the revised certificate, including

its pregnancy checkbox, is complete for all 50 states (noting that

California implemented a different checkbox than that on the U.S.

Standard Certificate of Death), allowing NCHS to resume the routine

publication of maternal mortality statistics. However, an evaluation

of data quality indicated some errors with the reporting of maternal

deaths (deaths within 42 days of pregnancy) following adoption of

the checkbox, including overreporting of maternal deaths among

older women. Therefore, NCHS has adopted a new method (to be

called the 2018 method) for coding maternal deaths to mitigate

these probable errors. The 2018 method involves further restricting

application of the pregnancy checkbox to decedents aged 10–44

years from the previous age group of 10–54. In addition, the 2018

method restricts assignment of maternal codes to the underlying

cause alone when the checkbox is the only indication of pregnancy

on the death certificate, and such coding would be applied only to

decedents aged 10–44 based solely on the checkbox when no other

pregnancy information is provided in the cause-of-death statement.

Based on the new method, a total of 658 deaths were identified in

2018 as maternal deaths. The maternal mortality rate for 2018 was

17.4 deaths per 100,000 live births, and the rate for non-Hispanic

black women (37.3) was 2.5 to 3.1 times the rates for non-Hispanic

white (14.9) and Hispanic (11.8) women. Rates also increased with

age. Maternal mortality rates calculated without using information

obtained from the checkbox are also presented for 2002, 2015,

2016, 2017, and 2018 to provide comparisons over time using a

comparable coding approach across all states.

Keywords: death certificate • pregnancy status checkbox •

National Vital Statistics System

Introduction

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

National Center for Health Statistics

National Vital Statistics System

NCHS reports can be downloaded from: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/index.htm.

2 National Vital Statistics Reports, Vol. 69, No. 2, January 30, 2020

Implementation of the pregnancy checkbox item accounts

for a substantial increase in both the number of deaths identified

as maternal and the resulting maternal mortality rates (10–12),

with the impact varying by age, race and Hispanic origin, and

state. When combining data for all states where the number of

states adopting the checkbox increased differentially over time,

the observed trend in maternal mortality appears to indicate

an increase. However, it has been shown that this is mainly a

reflection of the states’ incremental implementation of the

checkbox over a 14-year period. It could not be determined

whether this effect is due to better ascertainment of true maternal

deaths, or to increases in deaths coded as maternal in error, or

some combination of both (11,13).

Coding procedures adopted with the checkbox

implementation in 2003 and used through 2017 (referred to

throughout this report as the 2003–2017 method) are based on

causes of death reported on death certificates and information

on pregnancy status reported in the checkbox item. The

coding instructions specify assigning a maternal code from the

International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision (ICD–10)

to all medical conditions reported if there is any indication of

pregnancy on a death certificate. Such indications include when

causes specific to pregnancy, delivery, or the puerperium are

reported in the cause-of-death section of the death certificate;

pregnancy is mentioned among the medical conditions reported

on the death certificate; or a response in the checkbox item that

indicates the woman had been pregnant at the time of death

or in the preceding year. If the checkbox response is the only

indication of a pregnancy in the past year on the death certificate,

the term “checkbox-only” is used to refer to these deaths. The

2003–2017 method restricted application of the checkbox item to

ages 10–54 years (see the next section on “Evidence and Effects

of Checkbox Errors” for more details on reporting patterns for

women aged 55 and over).

Based on research on the quality of maternal mortality data

using information obtained from the checkbox (10,11), NCHS has

adopted a new method for coding maternal deaths to mitigate

some of the quality concerns identified by multiple evaluations

of information on pregnancy status provided in the checkbox.

NCHS has also adopted a new method for displaying the coded

causes of death for maternal deaths in the mortality data file.

This report describes the changes in how NCHS will code and

release maternal mortality data and provides maternal mortality

rates for 2018 using the new coding method. The 2018 maternal

mortality rates using the new method are compared with rates

calculated using the 2003–2017 method to highlight differences

that result from applying the two coding methods. Maternal deaths

for 2015–2018 were also recoded without using the information

in the checkbox, as would have been the case before 2003. The

rates for 2015–2018 were then compared with the rate for 2002

to provide comparable information on trends in maternal deaths.

Considerations for assessing trends are also discussed.

Evidence and Effects of Checkbox Errors

Recent research has demonstrated that errors are common

in the reporting of pregnancy status using the checkbox. Rossen

et al. reviewed the literature on reporting errors in the checkbox

and reported a range of false-positive rates (i.e., indication of

pregnancy or pregnancy in the past year when the decedent was

not actually pregnant or pregnant in the last year) as high as

50% (11). An analysis conducted internally by NCHS that linked

hospital records with death certificates for selected hospitals

suggested potential false positive rates of 54% and 56% for the

checkbox in 2014 and 2016, respectively. Note, however, that

these results are not based on nationally representative data

(see Technical Notes, “Checkbox item analysis based on National

Hospital Care Survey data linked to National Death Index,” for

further information).

Davis et al. (12) examined patterns by age and discussed the

likelihood of misclassification with increasing age. Subsequent

research supported the thought that false positives resulting from

errors in the checkbox item were concentrated among decedents

in their 40s and 50s (14). Research on data from four states

(Georgia, Louisiana, Michigan, and Ohio) found that a pregnancy

indicated by the checkbox for those under age 40 was more likely

to be corroborated, and a pregnancy for those aged 45 and over

was more likely to not be corroborated—for example, 19% of

decedents aged 45–49 with a positive checkbox response (i.e.,

pregnant or pregnant in the last year) had actual evidence of a

pregnancy (14).

To evaluate the use of the checkbox for women aged 40

and over, checkbox entries were tabulated by age of decedent

and compared with the number of births for these age groups.

In the NVSS mortality data for 2013 (including all states except

Alabama, Alaska, Colorado, Hawaii, Massachusetts, North

Carolina, Virginia, and West Virginia, which did not use the

standard checkbox in 2013), 797 deaths of women aged 40 and

over had a checkbox entry indicating they were pregnant at the

time of death or pregnant in the last year from any cause; 652

of these pregnancies were reported as occurring among those

aged 45 and over; and 147 of these pregnancies were reported

as occurring over age 85. The number of decedents reported

as pregnant or pregnant in the last year is unrealistically large

at older ages and, by ages 60–64, far surpasses the reported

number of women giving birth in those age groups (Table A).

The exact cause of these errors is unclear. If the checkbox

errors are random (i.e., certifiers are selecting the wrong

checkbox item with the same regularity across all ages, or even

with a lower error rate at the older ages), the absolute number

of errors would be larger at the older ages simply because the

volume of all deaths increases as age increases. To illustrate this,

Table B uses data from before the checkbox was implemented

to show the number of female deaths for decedents under age

25 through 54 from all causes, the number of maternal deaths

identified from the cause-of-death section of the certificate,

and the number of maternal deaths that potentially would be

added assuming that the checkbox would have introduced a

hypothetical constant error rate of 0.03%. The number of deaths

potentially added in error increases with age. For those aged

45–54, an error rate in the checkbox item of 0.03% could result

National Vital Statistics Reports, Vol. 69, No. 2, January 30, 2020 3

in an additional 74 deaths, inflating the actual number of maternal

deaths by 452%. For the data years used for Table B (1999–2002,

before the checkbox was implemented), no maternal deaths were

reported beyond age 54.

When information on pregnancy is found only in the

checkbox with no mention of maternal causes in the cause-of-

death section, the net result of errors in reporting pregnancy

status is a substantial overreporting of maternal mortality,

especially for older women (12,15,16). In the study by Catalano

et al., ages 45 and over were identified as those for which a

response in the pregnancy checkbox is more likely to be an error

(14). The results from Table B align with this finding.

New Approach for Coding Maternal

Deaths: Description of 2018 Method

A new method (referred to as the 2018 method) for coding

maternal deaths has been adopted to mitigate the effect of

reporting errors in the checkbox item and to retain cause-of-

death detail lost in the application of the 2003–2017 method.

Table A. Number of births and deaths with positive pregnancy

responses in the checkbox: United States, 2013

[Deaths could include any cause (International Classification of Diseases, 10th

Revision codes A00–Y89) but checkbox entry indicates pregnant at time of death,

pregnant within 42 days of death, or pregnant between 43 days and 1 year of

death]

Age Births Deaths

40–44 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 134,540 145

45–49 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 10,329 89

50–54 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 780 148

55–59 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 74 33

60–64 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 7 51

65–69 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . – 45

70–74 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . – 51

75–79 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . – 46

80–84 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . – 42

85 and over . . . . . . . . . . . . . . – 147

– Quantity zero.

NOTE: Alabama, Alaska, Colorado, Hawaii, Massachusetts, North Carolina, Virginia, and

West Virginia did not have the standard checkbox in 2013.

SOURCE: NCHS, National Vital Statistics System.

This new method will be used for all jurisdictions (see Technical

Notes, “California data and coding methods”). Procedures will

generally remain the same for records with reported terms or

phrases indicating pregnancy and obstetric causes in the cause-

of-death statement for all ages. The 2018 method introduces two

changes to the 2003–2017 method in the coding of maternal

deaths. The first change is that coding of maternal (and late

maternal) deaths will further restrict application of the checkbox

item to decedents aged 10–44 instead of 10–54 as is done with

the 2003–2017 method. The checkbox will not be used for

decedents aged 45 and over in light of the findings discussed

above on the checkbox quality for women in this age group

(14). The result is that for female decedents aged 45 and over,

maternal codes will not be assigned if the only indication of a

pregnancy was in the checkbox using the 2018 coding method.

This change does not affect coding procedures for decedents

aged 10–44.

The second change involves how causes of death for

maternal (and late maternal) deaths are reported on the mortality

file. When the pregnancy checkbox item indicated that the

decedent was pregnant or pregnant within the preceding year,

application of the 2003–2017 method assigned all medical

conditions reported on the death certificate for decedents aged

10–54 to maternal codes, rather than to nonmaternal codes for

the causes listed on the certificate. However, doing so provided

no means of identifying the record as a checkbox-only case

without additional information beyond what is normally available

in the standard data files (e.g., literal text), and no way to

identify potential errors for specific records. In addition, for the

checkbox-only records, the maternal codes assigned often retain

less detail about the causes reported. The change implemented

with the 2018 coding method for decedents aged 10–44 only

codes the underlying cause of death to a maternal code when

the checkbox is the only indicator of a pregnancy in the last year

(i.e., only the underlying cause will be modified, except in cases

where the underlying cause is an external or incidental cause,

which is the practice regardless of method). The result of this

change is that most of the original detail lost when applying the

2003–2017 method is retained, and the record better reflects

what was actually reported on the death certificate. In addition,

when using this new format, checkbox-only records will be

flagged with an indicator on the mortality files.

Table B. Number of deaths potentially added if 0.03% of certificates have a checkbox in error

Age All female deaths Maternal deaths

Maternal

mortality rate

(deaths per 100,000

live births)

Number of deaths

potentially added if

0.03% of certificates

have a checkbox in error

Maternal mortality

rate including those

potentially added in

error (deaths per

100,000 live births)

Under 25 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 39,796 384 6.5 12 6.7

25–39 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 102,796 1,018 10.4 31 10.7

40–54 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 324,934 141 37.0 97 62.4

40–44 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 79,796 120 33.2 24 39.8

45–54 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 245,138 21 107.6 74 486.6

NOTES: Using counts from the National Vital Statistics System, mortality data for 1999–2002 for all female and maternal deaths for the ages are shown for illustration. These numbers were

previously published according to how maternal deaths were determined before 2003. The error rate of 0.03% was selected based on the percentage of female decedents in 2013 aged 55 and

over with a positive pregnancy checkbox.

SOURCE: NCHS, National Vital Statistics System, Mortality.

4 National Vital Statistics Reports, Vol. 69, No. 2, January 30, 2020

Generally, more information is reported on death certificates

than is directly reflected in the underlying cause of death. This

additional information is captured in multiple cause-of-death

data that are available on the data files. Multiple cause-of-death

data are retained in two forms: entity axis and record axis. The

entity axis preserves details on where causes associated with

the codes were reported on the death certificate. The record

axis reflects some transformation of the entity axis codes to

facilitate analysis, eliminates duplicate codes, and includes the

underlying cause code. Record axis and entity axis generally

would differ somewhat between coding methods (for examples,

see Technical Notes). Using the 2018 method, for checkbox-only

records, those aged 10–44 would have only one maternal code,

which would appear in the record axis as the underlying cause.

The entity axis would consist entirely of nonmaternal codes. Also

using the 2018 method, checkbox-only records for those aged

45–54 would consist only of nonmaternal codes in both entity

and record axis. For the records with terms or phrases related to

pregnancy or obstetric conditions, in the cause-of-death section

of the certificate, the multiple-cause data would be the same as

before.

The changes incorporated with the 2018 method (see

Technical Notes for examples) are summarized as:

• Coding of maternal deaths will restrict application of the

checkbox item to decedents aged 10–44. The checkbox will

not be applied in the coding of cause of death for decedents

aged 45 and over when no other cause-of-death information

related to pregnancy is indicated on the certificate; however,

the original checkbox entries will be retained on the file for

this age group.

• If the checkbox is the only indication of a pregnancy for female

decedents aged 10–44, a maternal code will be assigned as

the underlying cause, except in cases where the underlying

cause is an external or incidental cause, which would not be

coded as maternal regardless of coding method. A maternal

code will be assigned only to the underlying cause and not

to other conditions reported on the certificate. The other

original causes will be retained on the record.

Cases in which a pregnancy or obstetric condition is

reported in the cause-of-death section will continue to be coded

as maternal deaths regardless of age.

Maternal Mortality in 2018

In 2018, a total of 658 women were identified as having

died of maternal causes in the United States (Table 1) using the

2018 coding method. The maternal mortality rate for 2018 was

17.4 deaths per 100,000 live births. The maternal mortality rate

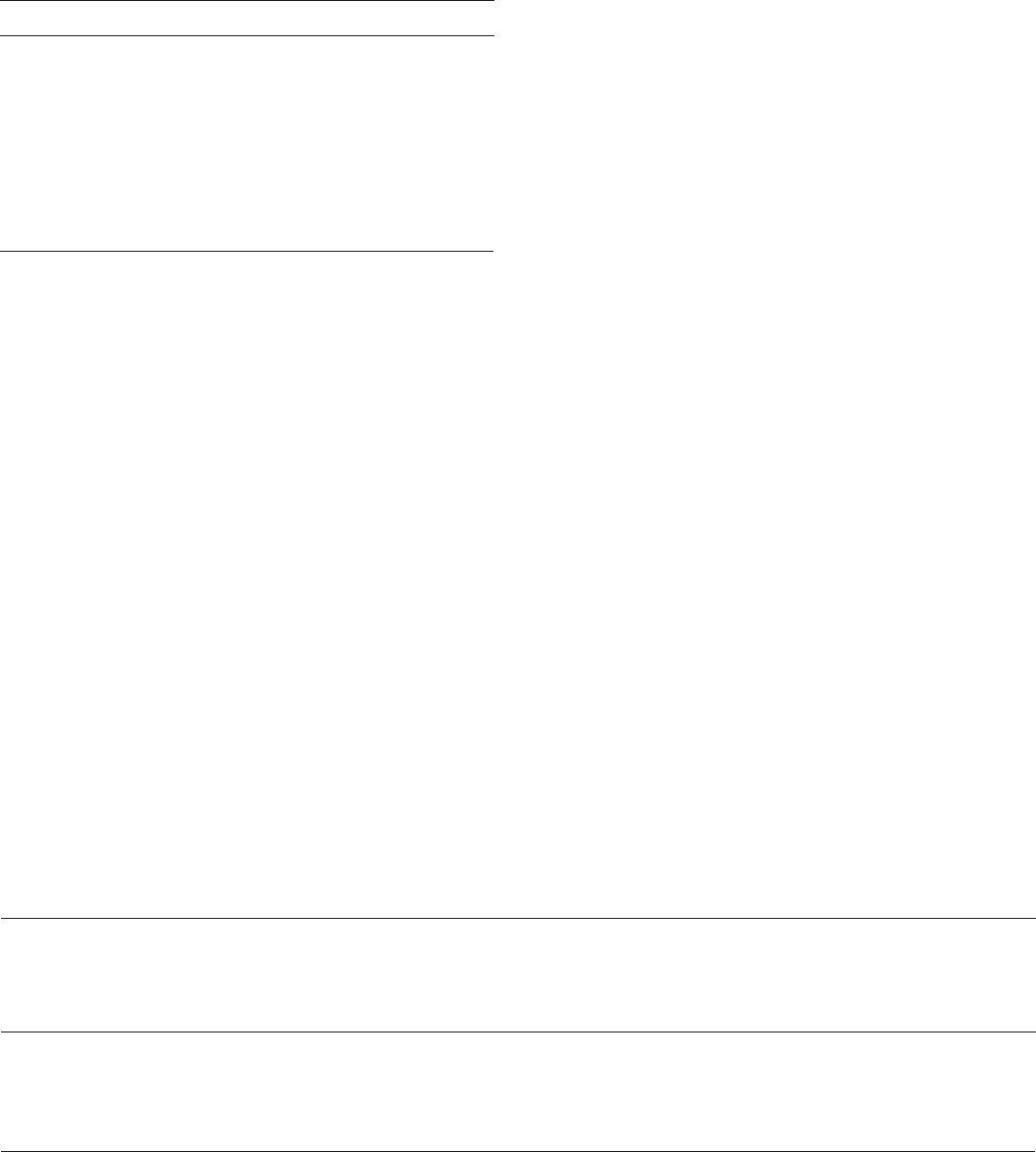

increases with successively older age groups (Figure 1), with the

rate for women aged 40 and over (81.9) equal to 7.7 times that

for women under age 25 (10.6).

Figure 1. Maternal mortality rates, by age: United States, 2018

Deaths per 100,000 live births

SOURCE: National Vital Statistics System, Mortality.

17.4

10.6

16.6

81.9

0 20 40 60 80 100

All ages

Under 25

25–39

40 and over

National Vital Statistics Reports, Vol. 69, No. 2, January 30, 2020 5

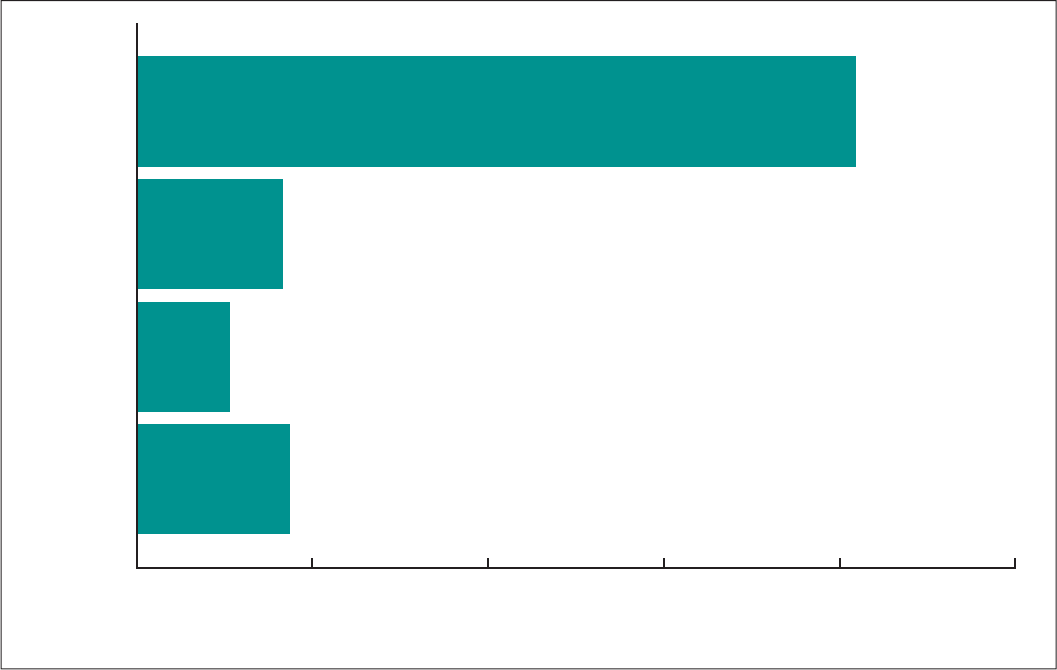

As shown in Figure 2, the maternal mortality rate for non-

Hispanic black women (37.3 deaths per 100,000 live births) was

2.5 times the rate for non-Hispanic white (14.9) and 3.1 times the

rate for Hispanic women (11.8) (Note: Rates are shown by single

race group; see Technical Notes for information on bridged-race

results and more information on the differences between single

and bridged race). In 2018, the ratio for non-Hispanic white

women to Hispanic women was 1.3.

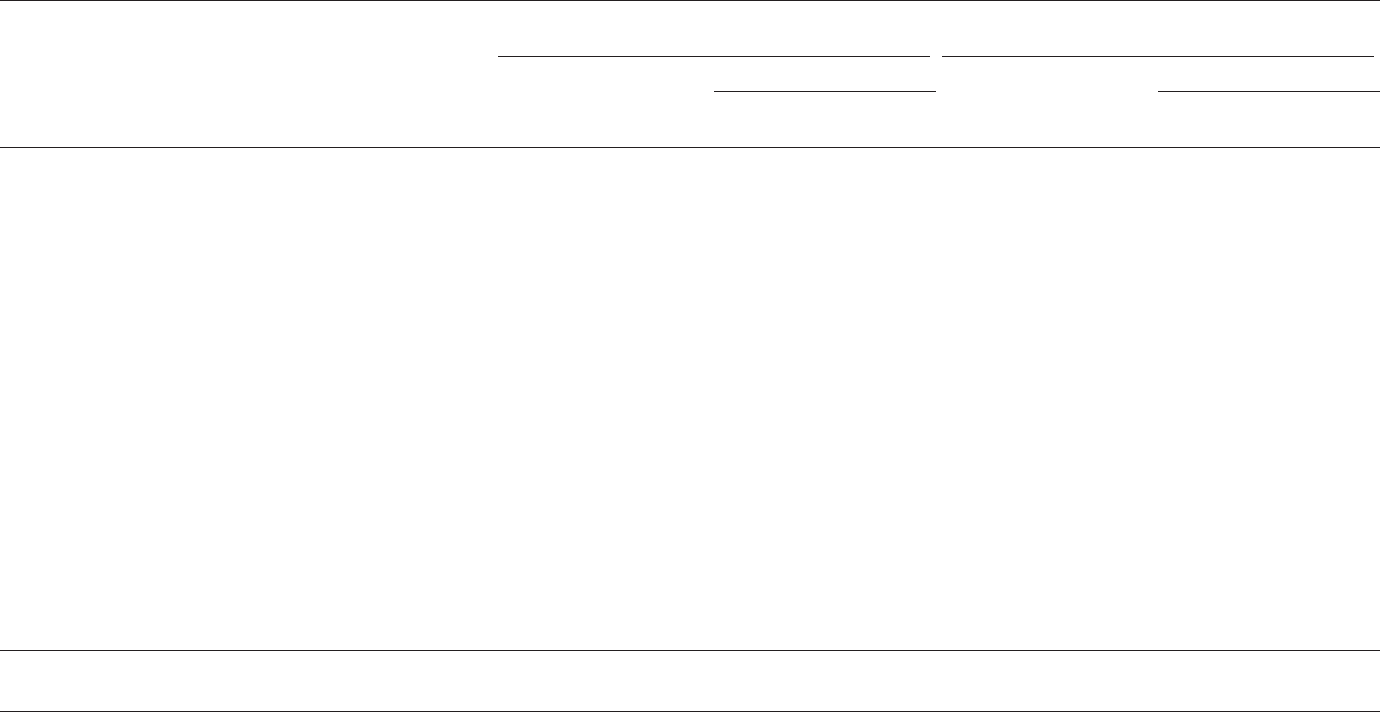

Maternal deaths may be viewed using more detailed causes

of death, which are broadly divided into direct and indirect

obstetric causes (Table 2; note that some of the more detailed

cause categories have vague titles or small numbers). Using the

2018 method, more deaths were classified to direct obstetric

causes (A34, O00–O95) (77%) than to indirect obstetric causes

(O98–O99) (23%) in 2018. Figure 3 shows the percent distribution

of selected maternal death causes (which each account for

4%–6% of maternal deaths), a category for indirect causes

(accounts for 23% of deaths), and the category “Remaining direct

obstetric causes,” which encompasses many codes (e.g., O10,

O12, O21–O43, O47–O66, O68–O71, O73–O75, and O95) and

accounts for about one-half of the deaths. Described in terms

of maternal mortality rates, Abortive outcomes, which primarily

are ectopic pregnancies, and Hemorrhage of pregnancy and

childbirth and placenta previa both occurred at a rate of 0.8

deaths per 100,000 live births in 2018. The rate for Eclampsia

and pre-eclampsia was 0.9 deaths per 100,000 live births, and

the rate for Obstetric embolism was 1.1 deaths per 100,000 live

births.

Not included in Figures 1–3 are the 277 deaths that were

reported as occurring more than 42 days but less than 1 year after

delivery in 2018, for a late maternal mortality rate of 7.3 deaths

per 100,000 live births. Late maternal deaths are not included as

part of the official maternal mortality rate (see Technical Notes,

“Late maternal deaths”).

Results From 2018 Method Compared

With 2003–2017 Method

Tables 1 and C show maternal mortality rates for 2018

calculated based on both the 2003–2017 method and the 2018

method. Given that the change in use of the checkbox with the

2018 method is applied to women aged 45–54, the maternal

mortality rates are the same for age groups under 25, 25–39,

and 40–44 for both methods (Table 1). The ratio of the maternal

mortality rates for those aged 40 and over to under age 25

(Table C) is 16.6 when using the 2003–2017 method and 7.7

when using the 2018 method, reflecting the higher error rate

in identifying maternal deaths at older ages in the 2003–2017

method and the decision to restrict the use of the checkbox to

those under age 45. For women aged 45 and over, there are

only seven deaths when using the 2018 method’s expanded

SOURCE: National Vital Statistics System, Mortality.

Deaths per 100,000 live births

0

10

20

30

40

11.8

Hispanic

37.3

Non-Hispanic black

14.9

Non-Hispanic white

Race and Hispanic origin

Figure 2. Maternal mortality rates, by single race and Hispanic origin: United States, 2018

6 National Vital Statistics Reports, Vol. 69, No. 2, January 30, 2020

restriction on age, which results in a rate that does not meet

NCHS standards of reliability (73.1). Using the 2003–2017

checkbox method, the ratio of the maternal mortality rates

among those aged 45 and over to those under age 25 is 124.1,

and 6.9 when using the 2018 method, but these again are based

on rates that are statistically unreliable.

Maternal mortality rates for non-Hispanic black

women (Tables 1 and D) were consistently higher than for

non-Hispanic white (Note: Rates are shown by single race group;

see Technical Notes for information on bridged-race results and

more information on the differences between single and bridged

race) and Hispanic women based on both methods. The ratio

of the rates for non-Hispanic black women to non-Hispanic

white women was 2.4 with the 2003–2017 method and 2.5 with

the 2018 method. The ratio for non-Hispanic black to Hispanic

women was 3.2 using the 2003–2017 method and 3.1 using the

2018 method.

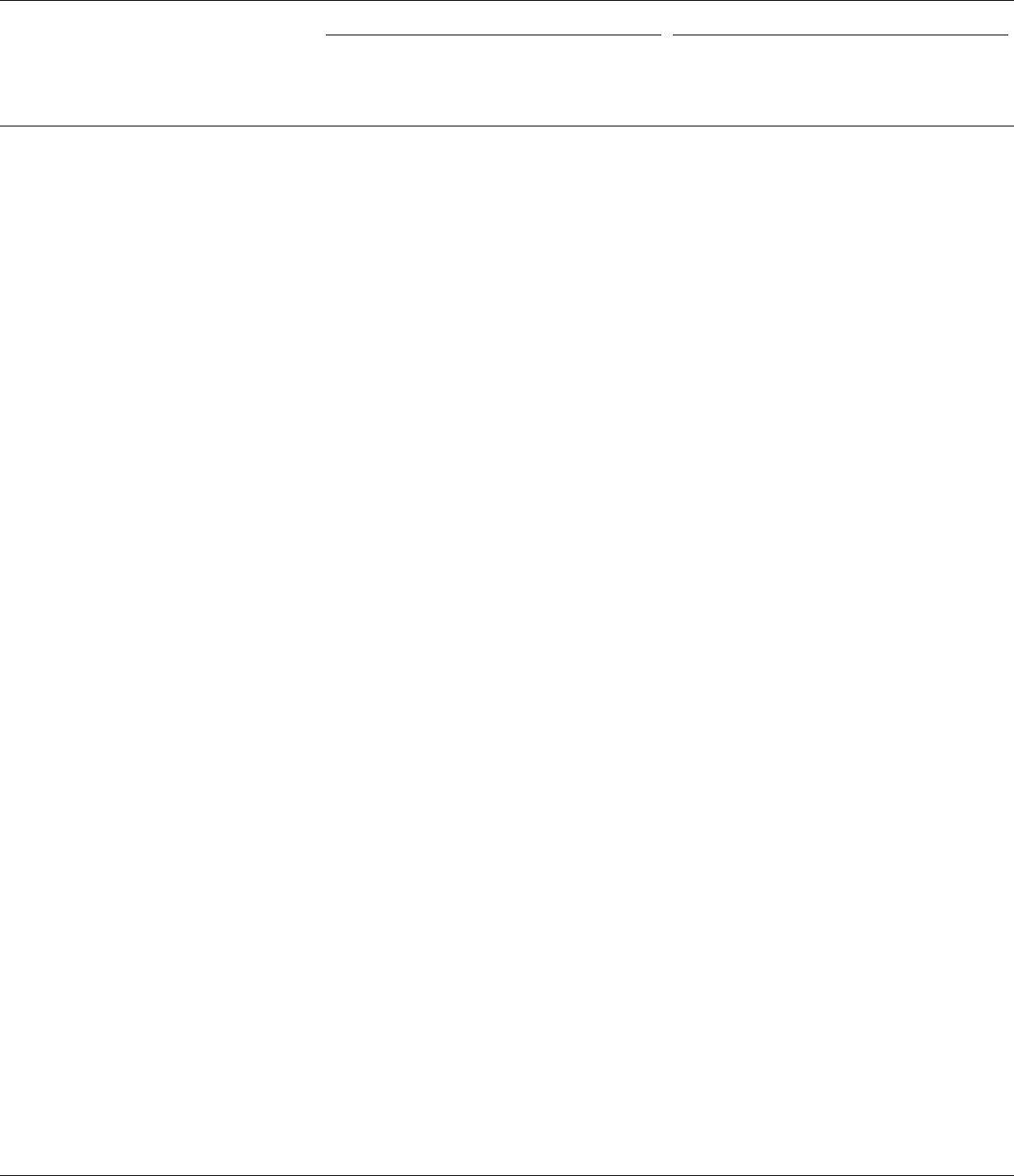

Table 2 shows numbers and maternal mortality rates by

cause based on the different coding methods. The distribution of

the causes of death is similar for these two methods (Figure 4).

In 2018, the maternal mortality rate for indirect obstetric causes

was 5.1 deaths per 100,000 live births using the 2003–2017

method, whereas when using the 2018 method, the rate was 3.9.

For direct obstetric causes, the rate was 15.4 deaths per 100,000

live births using the 2003–2017 method, compared with 13.4

when using the 2018 method. Within the direct causes, rates

were 0.8 deaths per 100,000 live births for Other complications

predominantly related to the puerperium using the 2003–2017

method, and 0.7 using the 2018 method; 1.0 for Eclampsia and

pre-eclampsia using the 2003–2017 method, and 0.9 using

the 2018 method; and 1.2 for Obstetric embolism using the

2003–2017 method, and 1.1 using the 2018 method. Maternal

mortality rates increase with increasing age for the different

causes of death regardless of method.

Comparison of Rates With Those of

Pre-checkbox Era

NCHS last published information on the U.S. maternal

mortality trend in 2002. It is not appropriate to compare maternal

mortality for 2018 with previous years when the checkbox had

not been adopted by all states and the number of states adopting

the checkbox increased each year. Observed changes in the rate

reflect the increasing number of states adopting the checkbox

rather than a change in the risk of maternal death. The maternal

Figure 3. Percent distribution of maternal deaths, by

cause of death: United States, 2018

0

20

40

60

80

100

2018 method

SOURCE: National Vital Statistics System, Mortality.

22.6

52.3

4.3

6.5

4.6

5.3

4.4

Remaining direct obstetric

causes

Total indirect obstetric causes

Other complications

predominantly related to

the puerperium

Obstetric embolism

Hemorrhage and placenta previa

Eclampsia and pre-eclampsia

Abortive outcome

Percent

Indirect

obstetric

causes

Direct

obstetric

causes

Table C. Maternal mortality rates and ratio of maternal

mortality rates, by coding method and maternal age:

United States, 2018

[Rates are per 100,000 live births. Ratio of maternal mortality rates is for

specified maternal age to those under age 25]

With checkbox

(2003–2017

coding method)

With checkbox for

ages 44 and under;

without checkbox

for 45 and over

(2018 coding method)

Age Rate Ratio Rate Ratio

Under 25 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 10.6 1.0 10.6 1.0

25–39 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 16.6 1.6 16.6 1.6

40 and over . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 175.7 16.6 81.9 7.7

40–44 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 82.6 7.8 82.6 7.8

45 and over . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1,315.9 124.1 *73.1 *6.9

* Figure does not meet NCHS standards of reliability.

SOURCE: NCHS, National Vital Statistics System.

Table D. Maternal mortality rates and ratio of maternal

mortality rates, by coding method and single race and

Hispanic origin: United States, 2018

[Rates are per 100,000 live births. Ratio of maternal mortality rates is for

non-Hispanic black women compared with non-Hispanic white and Hispanic

women]

Race and Hispanic origin

With checkbox

(2003–2017

coding method)

With checkbox for

ages 44 and under;

without checkbox

for 45 and over

(2018 coding method)

Rate Ratio Rate Ratio

Non-Hispanic white . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 18.2 2.4 14.9 2.5

Non-Hispanic black . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 43.5 1.0 37.3 1.0

Hispanic . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 13.7 3.2 11.8 3.1

SOURCE: NCHS, National Vital Statistics System.

National Vital Statistics Reports, Vol. 69, No. 2, January 30, 2020 7

mortality rate calculated without using the checkbox, as would

have been done before 2003 (referred to as the pre-2003

method), provides statistics calculated in the most equivalent

way possible (i.e., without the checkbox) for the entire United

States over time (10). These comparisons are provided in this

report to show comparisons using the most recent data and

as many recent time points as possible. As of this report, data

have been recoded without using the checkbox for only the

2015–2018 data years.

Table E shows maternal mortality rates for 2002 (8.9),

2015 (8.7), 2016 (8.7), 2017 (11.5), and 2018 (8.7). Except for

2017 (11.5), the rates were not statistically different from the

rate in 2002 (8.9). These results are similar to the other reports

previously mentioned, which also demonstrate that the maternal

mortality rate did not increase significantly either after accounting

for the staggered implementation of the checkbox by states

(using the modeled approach) (11) or as if the checkbox had

never been implemented (10). It is possible that recoding cause

of death without using the checkbox can miss some deaths that

would have been identified had the checkbox not been present,

such as if the certifier did not list a maternal cause in the cause-

of-death section of the death certificate because pregnancy was

indicated in the checkbox.

Figure 4. Percent distribution of maternal deaths, by cause of death using two coding methods: United States, 2018

Maternal Mortality Data Release Moving

Forward

Starting with the 2018 data year, the 2018 method will be

incorporated as part of NCHS’ standard production of the public-

use mortality data. The 2018 mortality data are being released

at the same time as this report and will include maternal deaths

coded according to the 2018 method. All official statistics on

maternal mortality from 2018 and subsequent years will be

based on the 2018 method.

Starting with the 2018 data file, the underlying-cause and

multiple-cause (both entity axis and record axis) fields will be

the same as originally coded for the records reporting terms

and phrases indicating pregnancy or obstetric conditions

0

20

40

60

80

100

2018 method2003–2017 method

NOTE: Totals may not add to 100 due to rounding.

SOURCE: National Vital Statistics System, Mortality.

Remaining direct obstetric causes

Total indirect obstetric causes

Other complications predominantly

related to the puerperium

Obstetric embolism

Hemorrhage and placenta previa

Eclampsia and pre-eclampsia

Abortive outcome

Percent

22.6

52.3

4.3

6.5

4.6

5.3

4.4

24.8

53.0

3.7

5.7

4.1

4.9

3.7

Indirect

obstetric

causes

Direct

obstetric

causes

Table E. Maternal mortality rates using the pre-2003 method:

United States, 2002 and 2015–2018

[Rates are per 100,000 live births]

Year Number of deaths Rate

2002 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 357 8.9

2015 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 345 8.7

2016 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 345 8.7

2017 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 442 11.5

2018 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 331 8.7

NOTE: Data for 2002 are included for comparison with the 2015–2018 values.

SOURCE: NCHS, National Vital Statistics System.

8 National Vital Statistics Reports, Vol. 69, No. 2, January 30, 2020

for decedents of all ages. For checkbox-only records, not all

conditions on the record will be assigned maternal codes as

was previously done. Instead, only the underlying cause will be

modified. Entity axis fields will not be modified. In addition, in

the record axis fields, the nonmaternal code that would have

been selected as the underlying cause if no checkbox item had

been available will be flagged (see data documentation for the

2018 mortality file for details). For decedents aged 45–54 with

a positive checkbox item and no reported information related to

pregnancy in the cause-of-death section, the underlying-cause

and multiple-cause fields will reflect coding done without using

the checkbox item; see Technical Notes for an illustration with a

couple of examples. The checkbox value will still be available in

the mortality files as a separate field.

For the data files that have been released previously

(2003–2017), maternal records are being recoded without

using the checkbox item (pre-2003 method) and will also be

recoded according to the 2018 method. These data, along with

the original coding (2003–2017 method) and the pregnancy

checkbox item, will be incorporated into an additional, separate

restricted-use data file that will be available to researchers

through the NCHS Research Data Center. The official data files

for 2003–2017 already released will not be changed. Reclassified

data for 2015–2017 are being released along with this report.

Data for 2003–2014 will be added to this file as the recoding for

each year is completed. These data will provide researchers with

access to cause-of-death codes using alternate coding methods

and provide maximum flexibility for analysis using different

methods and assumptions. As addressed earlier, the pre-2003

method underestimated maternal deaths, the 2003–2017

method overestimated maternal deaths for older women, and

the 2018 method is designed to lessen the effect of likely errors

in the checkbox. Trend analyses for data pre-2018 using either

the 2003–2017 or 2018 method are limited by the incremental

implementation of the checkbox.

Implications Related to Use of 2018

Method

The checkbox item was added to correct for underestimation,

and initial results showed an increase in reporting of maternal

deaths. With time, however, questions arose about whether

the increase stemmed from an unknown mixture of improved

measurement and increased misclassification (12,13,15). The

2018 method is intended to mitigate errors (14) in the pregnancy

checkbox item and provide an improved estimate of maternal

mortality. However, it does not correct all errors, nor does it

address all issues with the data. The 2018 method may result

in an underestimate of maternal mortality at ages 45 and over

and may still overestimate maternal mortality for ages 10–44. If

certifiers alter what they report in the cause-of-death statement

because of the availability of the checkbox, that might affect the

adequacy of the 2018 method. The 2018 method will not have

an impact on records where pregnancy may have contributed

to death but the certifier failed to report it in either the cause-

of-death statement or the checkbox item. Other modifications—

such as changes in ways certifiers completed cause-of-death

information on the death certificate, changes in guidance

provided to certifiers, shifts in completing death certification on

paper compared with electronic death registration, or changes

in outreach to query the quality of the information over time—

may be other factors that could potentially have influenced the

balance between improvement and misclassification captured

in the checkbox item but cannot be easily quantified. With the

exception of external causes, the 2018 coding method also does

not address cases in which the cause of death was incidental

to pregnancy (i.e., the decedent was pregnant in the last year,

but pregnancy was not a factor contributing to death). The

expectation is that more deaths are identified as maternal deaths

than appropriate in this scenario, because information on the

death certificate is typically insufficient to exclude causes that

may, in fact, be incidental.

Additional efforts will be needed to identify and correct

errors and improve reporting. Linking deaths for women of

reproductive age to birth and fetal death records as part of routine

vital statistics reporting in NVSS can help detect cases that fail

to report pregnancies in the past year as well as help investigate

checkbox-only cases that do not seem to have corroborating

indications of a pregnancy in the past year. Guidance on death

certificate reporting for certifiers can be effective, especially for

certifiers who are not familiar with the task of completing a death

certificate. A key step in any effective improvement is to ensure

that the accuracy and quality of information is incorporated into

vital statistics data as it is originally recorded.

References

1. World Health Organization. World health statistics, 2018:

Monitoring health for the SDGs, sustainable development goals.

Geneva, Switzerland. 2018. Available from: https://apps.who.int/

iris/bitstream/handle/10665/272596/9789241565585-eng.pdf.

2. Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Healthy People

2020. Maternal, infant, and child health objectives. Available from:

https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/

maternal-infant-and-child-health/objectives.

3. World Health Organization, United Nations International Children’s

Emergency Fund, United Nations Fund for Population Activities,

World Bank Group, United Nations Population Division. Trends

in maternal mortality: 1990 to 2015. 2015. Available from:

https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/194254/

9789241565141_eng.pdf;jsessionid=59889EA1DABF6E

8A9D61747C035432B7?sequence=1.

4. Creanga AA. Maternal mortality in the United States: A review

of contemporary data and their limitations. Clin Obstet Gynecol

61(2):296–306. 2018.

5. MacDorman MF, Declercq E, Thoma ME. Trends in maternal

mortality by sociodemographic characteristics and cause of

death in 27 states and the District of Columbia. Obstet Gynecol

129(5):811–8. 2017.

6. MacKay AP, Rochat R, Smith JC, Berg CJ. The check box:

Determining pregnancy status to improve maternal mortality

surveillance. Am J Prev Med 19(1 Suppl):35–9. 2000.

7. Horon IL, Cheng D. Enhanced surveillance for pregnancy-

associated mortality—Maryland, 1993–1998. JAMA 285(11):

1455–9. 2001.

National Vital Statistics Reports, Vol. 69, No. 2, January 30, 2020 9

8. Building U.S. capacity to review and prevent maternal deaths.

Report from maternal mortality review committees: A view into

their critical role. 2017. Available from: https://www.cdcfoundation.

org/sites/default/files/files/MMRIAReport.pdf.

9. Zaharatos J, St Pierre A, Cornell A, Pasalic E, Goodman D. Building

U.S. capacity to review and prevent maternal deaths. J Womens

Health (Larchmt) 27(1):1–5. 2018.

10. Hoyert DL, Uddin SFG, Miniño AM. Evaluation of the pregnancy

status checkbox on the identification of maternal deaths. National

Vital Statistics Reports; vol 69 no 1. Hyattsville, MD. National

Center for Health Statistics. 2020.

11. Rossen LM, Womack LS, Hoyert DL, Anderson RN, Uddin SFG.

The impact of the pregnancy checkbox and misclassification

on maternal mortality trends in the United States, 1999–2017.

National Center for Health Statistics. Vital Health Stat 3(44). 2020.

12. Davis NL, Hoyert DL, Goodman DA, Hirai AH, Callaghan WM.

Contribution of maternal age and pregnancy checkbox on maternal

mortality ratios in the United States, 1978–2012. Am J Obstet

Gynecol 217(3):352.e1–352.e7. 2017.

13. Joseph KS, Lisonkova S, Muraca GM, Razaz N, Sabr Y, Mehrabadi

A, Schisterman EF. Factors underlying the temporal increase in

maternal mortality in the United States. Obstet Gynecol 129(1):91–

100. 2017.

14. Catalano A, Davis NL, Petersen EE, Harrison C, Kieltyka L, You

M, et al. Pregnant? Validity of the pregnancy checkbox on death

certificates in four states, and characteristics associated with

pregnancy checkbox errors. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019 [Epub

ahead of print].

15. MacDorman MF, Declercq E, Cabral H, Morton C. Recent increases

in the U.S. maternal mortality rate: Disentangling trends from

measurement issues. Obstet Gynecol 128(3):447–55. 2016.

16. Baeva S, Archer NP, Ruggiero K, Hall M, Stagg J, Interis EC, et al.

Maternal mortality in Texas. Am J Perinatol 34(6):614–20. 2017.

17. Kochanek KD, Murphy SL, Xu JQ, Arias E. Deaths: Final data for

2017. National Vital Statistics Reports; vol 68 no 9. Hyattsville,

MD: National Center for Health Statistics. 2019.

List of Detailed Tables

1. Maternal mortality rates and number of maternal deaths, by

race and Hispanic origin and age: United States, 2018 ...... 10

2. Maternal mortality rates and number of maternal deaths by

coding method for selected causes, by age: United States,

2018 ............................................ 11

10 National Vital Statistics Reports, Vol. 69, No. 2, January 30, 2020

Table 1. Maternal mortality rates and number of maternal deaths, by race and Hispanic origin and age: United States, 2018

[Maternal causes are those assigned to categories of the International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision, 1992. Maternal deaths occur while pregnant or within

42 days of being pregnant. Race values are not bridged. Rates are per 100,000 live births]

Race and Hispanic origin and age

Maternal mortality (A34, O00–O95, O98–O99) Late maternal mortality (O96)

With checkbox

1

(2003–2017

coding method)

With checkbox for ages

44 and under

1

; without

checkbox for 45 and over

(2018 coding method)

With checkbox

1

(2003–2017

coding method)

With checkbox for ages

44 and under

1

; without

checkbox for 45 and over

(2018 coding method)

Rate

All persons

2

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 20.5 17.4 7.9 7.3

Under 25 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 10.6 10.6 5.6 5.6

25–39 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 16.6 16.6 7.0 7.0

40 and over . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 175.7 81.9 44.1 25.2

40–44 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 82.6 82.6 26.4 26.4

45 and over . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1,315.9 * 261.1 *

Non-Hispanic white . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 18.2 14.9 8.0 7.3

Under 25 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 10.5 10.5 5.6 5.6

25–39 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 13.8 13.8 6.8 6.8

40 and over . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 182.6 72.0 53.6 *

40–44 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 70.4 70.4 * *

45 and over . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1,635.9 * * *

Non-Hispanic black . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 43.5 37.3 14.5 13.9

Under 25 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 15.3 15.3 * *

25–39 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 38.2 38.2 14.5 14.5

40 and over . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 434.0 239.9 * *

40–44 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 243.9 243.9 * *

45 and over . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 2,431.0 * * *

Hispanic . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 13.7 11.8 5.1 4.5

Under 25 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 7.6 7.6 * *

25–39 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 12.4 12.4 4.5 4.5

40 and over . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 90.0 * * *

40–44 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . * * * *

45 and over . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . * * * *

Number

All persons

2

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 777 658 301 277

Under 25 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 96 96 51 51

25–39 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 458 458 194 194

40 and over . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 223 104 56 32

40–44 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 97 97 31 31

45 and over . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 126 7 25 1

Non-Hispanic white . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 357 291 157 142

Under 25 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 41 41 22 22

25–39 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 207 207 103 103

40 and over . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 109 43 32 17

40–44 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 39 39 16 16

45 and over . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 70 4 16 1

Non-Hispanic black . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 240 206 80 77

Under 25 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 27 27 15 15

25–39 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 137 137 52 52

40 and over . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 76 42 13 10

40–44 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 39 39 10 10

45 and over . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 37 3 3 –

Hispanic . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 121 105 45 40

Under 25 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 21 21 11 11

25–39 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 72 72 26 26

40 and over . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 28 12 8 3

40–44 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 12 12 3 3

45 and over . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 16 – 5 –

* Rate does not meet NCHS standards of reliability.

– Quantity zero.

1

California did not have the standard checkbox item.

2

Total includes more race and Hispanic groups than shown, including more than one race.

SOURCE: NCHS, National Vital Statistics System, Mortality.

National Vital Statistics Reports, Vol. 69, No. 2, January 30, 2020 11

Table 2. Maternal mortality rates and number of maternal deaths by coding method for selected causes, by age: United States, 2018

[Maternal causes are those assigned to categories of the International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision (ICD–10), 1992. Maternal deaths occur while pregnant or within 42 days of being pregnant]

Cause of death (based on ICD–10)

With checkbox

1

(2003–2017 coding method)

With checkbox for ages 44 and under

1

; without checkbox for

45 and over (2018 coding method)

All

persons Under 25 25–39

40 and over

All

persons Under 25 25–39

40 and over

Total 40–44

45 and

over Total 40–44

45 and

over

Rate per 100,000 live births

Maternal causes . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . (A34,O00–O95,O98–O99) 20.5 10.6 16.6 175.7 82.6 1,315.9 17.4 10.6 16.6 81.9 82.6 *

Direct obstetric causes . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . (A34, O00–O95) 15.4 7.6 12.8 126.8 68.2 846.0 13.4 7.6 12.8 67.7 68.2 *

Pregnancy with abortive outcome . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .(O00–O07) 0.8 * 0.8 * * * 0.8 * 0.8 * * *

Ectopic pregnancy . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .(O00) 0.6 * * * * * 0.6 * * * * *

Spontaneous abortion . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .(O03) * * * * * * * * * * * *

Medical abortion . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .(O04) * * * * * * * * * * * *

Other abortion . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .(O05) * * * * * * * * * * * *

Other and unspecified pregnancy with

abortive outcome . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . (O01–O02,O06–O07) * * * * * * * * * * * *

Other direct obstetric causes . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . (A34,O10–O92) 14.1 6.6 11.7 119.7 60.5 846.0 12.1 6.6 11.7 60.7 60.5 *

Eclampsia and pre-eclampsia . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . (O11,O13–O16) 1.0 * 1.0 * * * 0.9 * 1.0 * * *

Hemorrhage of pregnancy and childbirth

and placenta previa . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . (O20,O44–O46,O67,O72) 0.8 * 0.9 * * * 0.8 * 0.9 * * *

Complications predominantly related to

the puerperium . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . (A34,O85–O92) 1.9 * 1.9 * * * 1.9 * 1.9 * * *

Obstetrical tetanus . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . (A34) * * * * * * * * * * * *

Obstetric embolism . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .(O88) 1.2 * 1.2 * * * 1.1 * 1.2 * * *

Other complications predominantly related to

the puerperium . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . (O85–O87,O89–O92) 0.8 * 0.7 * * * 0.7 * 0.7 * * *

All other direct obstetric causes . . . . . . . . .(O10,O12,O21–O43,O47–O66,

O68–O71,O73–O75) 10.3 5.1 7.9 99.2 46.9 741.5 8.5 5.1 7.9 45.7 46.9 *

Obstetric death of unspecified cause . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .(O95) 0.6 * * * * * 0.6 * * * * *

Indirect obstetric causes . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .(O98–O99) 5.1 3.0 3.8 48.8 * 470.0 3.9 3.0 3.8 * * *

Death from any obstetric cause occurring more than 42 days

but less than 1 year after delivery . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . (O96)

2

7.9 5.6 7.0 44.1 26.4 261.1 7.3 5.6 7.0 25.2 26.4 *

See footnotes at end of table.

12 National Vital Statistics Reports, Vol. 69, No. 2, January 30, 2020

Table 2. Maternal mortality rates and number of maternal deaths by coding method for selected causes, by age: United States, 2018—Con.

[Maternal causes are those assigned to categories of the International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision (ICD–10), 1992. Maternal deaths occur while pregnant or within 42 days of being pregnant]

Cause of death (based on ICD–10)

With checkbox

1

(2003–2017 coding method)

With checkbox for ages 44 and under

1

; without checkbox for

45 and over (2018 coding method)

All

persons Under 25 25–39

40 and over

All

persons Under 25 25–39

40 and over

Total 40–44

45 and

over Total 40–44

45 and

over

Number

Maternal causes . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .(A34,O00–O95,O98–O99) 777 96 458 223 97 126 658 96 458 104 97 7

Direct obstetric causes . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . (A34, O00–O95) 584 69 354 161 80 81 509 69 354 86 80 6

Pregnancy with abortive outcome . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .(O00–O07) 29 3 21 5 5 – 29 3 21 5 5 –

Ectopic pregnancy . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .(O00) 24 3 19 2 2 – 24 3 19 2 2 –

Spontaneous abortion . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .(O03) 2 – 1 1 1 – 2 – 1 1 1 –

Medical abortion . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .(O04) – – – – – – – – – – – –

Other abortion . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .(O05) 1 – – 1 1 – 1 – – 1 1 –

Other and unspecified pregnancy with

abortive outcome . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . (O01–O02,O06–O07) 2 – 1 1 1 – 2 – 1 1 1 –

Other direct obstetric causes . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . (A34,O10–O92) 534 60 322 152 71 81 459 60 322 77 71 6

Eclampsia and pre-eclampsia . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . (O11,O13–O16) 38 2 27 9 5 4 35 2 27 6 5 1

Hemorrhage of pregnancy and childbirth

and placenta previa . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . (O20,O44–O46,O67,O72) 32 2 24 6 3 3 30 2 24 4 3 1

Complications predominantly related to

the puerperium . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . (A34,O85–O92) 73 10 52 11 8 3 71 10 52 9 8 1

Obstetrical tetanus . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . (A34) – – – – – – – – – – – –

Obstetric embolism . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .(O88) 44 5 33 6 5 1 43 5 33 5 5 –

Other complications predominantly related to

the puerperium . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . (O85–O87,O89–O92) 29 5 19 5 3 2 28 5 19 4 3 1

All other direct obstetric causes . . . . . . . . .(O10,O12,O21–O43,O47–O66,

O68–O71,O73–O75) 391 46 219 126 55 71 323 46 219 58 55 3

Obstetric death of unspecified cause . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .(O95) 21 6 11 4 4 – 21 6 11 4 4 –

Indirect obstetric causes . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .(O98–O99) 193 27 104 62 17 45 149 27 104 18 17 1

Death from any obstetric cause occurring more than 42 days

but less than 1 year after delivery . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . (O96)

2

301 51 194 56 31 25 277 51 194 32 31 1

* Rate does not meet NCHS standards of reliability.

– Quantity zero.

1

California did not have the standard checkbox item.

2

Late maternal death.

SOURCE: NCHS, National Vital Statistics System, Mortality.

National Vital Statistics Reports, Vol. 69, No. 2, January 30, 2020 13

Technical Notes

Tabulations of cause-of-death statistics in this report are

based solely on the underlying cause of death. The underlying

cause is defined by the World Health Organization as “the

disease or injury which initiated the train of morbid events

leading directly to death, or the circumstances of the accident or

violence which produced the fatal injury.” The underlying cause

is selected from the conditions entered by the medical certifier

in the cause-of-death section of the death certificate. When

more than one cause or condition is entered by the medical

certifier, the underlying cause is determined by the sequence

of conditions on the certificate, provisions of the International

Classification of Diseases (ICD), and associated selection rules

and modifications. Generally, more medical information is

reported on death certificates than is directly reflected in the

underlying cause of death. This is captured in National Center for

Health Statistics’ (NCHS) multiple cause-of-death data as entity

axis and record axis data.

For the years for which data has already been released,

Figures I and II provide some examples of how the recoded data

would be presented on a data file.

Checkbox item analysis based on National

Hospital Care Survey data linked to National

Death Index

The National Hospital Care Survey (NHCS) data linked

to the National Death Index (NDI) were analyzed by NCHS as

a case study to explore the potential accuracy of use of the

pregnancy checkbox item according to maternal mortality coding

procedures in U.S. death certificates. This analysis sought to

determine potential false positive (overuse) or false negative

(underuse) uses of the pregnancy checkbox. The linked NHCS–

NDI data contain information about hospital visits (inpatient and

emergency department encounters) in the year before death for

those patients who died. The analysis was based on the premise

that for a decedent currently pregnant or pregnant in the year

before death, the pregnancy checkbox would be used as it was

intended to indicate that the decedent was currently pregnant

(checkbox value of 2), pregnant within 42 days (value of 3), or

pregnant within 43 days to 1 year (value of 4). Assuming that the

person responsible for filling out the death certificate is aware of

the decedent’s recent medical history, including pregnancy, then

the expectation is that the checkbox would be correctly used. If

no evidence existed of a current pregnancy or pregnancy within

the year prior to death, or no information about pregnancy is

available, the expectation is that the checkbox would not be

used, and a value of 1 (not pregnant), 7 (not on certificate),

8 (not applicable), or 9 (unknown if pregnant within the past

year) would be used accordingly.

This analysis assessed whether overuse or underuse of the

checkbox occurred, using this unique source of linked hospital

care and death data. Overuse was assessed by first identifying

all death records in the linked file that had a pregnancy checkbox

value indication of 2, 3, or 4. Given that these decedents were

linked to hospitalization data in the previous year, the goal

Figure I. Example of record with checkbox and mention

of pregnancy or obstetric condition in cause-of-death

statement

I a) Rupture ectopic O00.9

pregnancy

b)

c)

II

Underlying cause O00.9

Entity axis codes—First two positions indicate where the

condition was reported (i.e., which line and where on the line)

11O009

Record axis codes—Underlying cause is listed first, followed

by other codes listed alphanumerically

O009

NOTES: For this example, the record would be coded the same with or without the

checkbox. The entity and record axis codes would be the same for both the 2003–2017

and 2018 methods.

SOURCE: NCHS, National Vital Statistics System, Mortality.

Pregnancy checkbox =

Pregnant at time of

death

Figure II. Example of checkbox-only record for decedent

aged 10–44

Coding using 2003–2017 method

I a) Brain stem herniation O99.3

b) Intracerebral hemorrhage O99.4

c) Brain arteriovenous

malformation O99.8

II

Underlying cause O99.8 (Other specified

diseases and

conditions

complicating

pregnancy, childbirth

and the puerperium)

Entity axis codes—First two positions indicate where the

condition was reported (i.e., which line and where on the line)

11O993 21O994 31O998

Record axis codes—Underlying cause is listed first, followed

by other codes listed alphanumerically)

O998 O993 O994

NOTES: For this example, the record would be coded differently with or without the

checkbox. Using the 2003–2017 method, all of the codes are O codes, whereas with the

2018 method, only the underlying cause is converted to an O code.

SOURCE: NCHS, National Vital Statistics System, Mortality.

Coding using 2018 method

I a) Brain stem herniation R58

b) Intracerebral hemorrhage I71.0

c) Brain arteriovenous

malformation I70.9

II

Underlying cause I71.0 O99.4 (Diseases of

the circulatory

system complicating

pregnancy, childbirth

and the puerperium)

Entity axis codes—First two positions indicate where the

condition was reported (i.e., which line and where on the line)

11R58 21I710 31I709

Record axis codes—Underlying cause is listed first, followed

by code that would have been the underlying cause without the

checkbox, followed by other codes listed alphanumerically

O994 I7101

1

I709 R58

1

The numeral 1 in the fifth position indicated the code that would be the underlying cause

without the checkbox.

Pregnancy checkbox =

Pregnant at time of

death

Pregnancy checkbox =

Pregnant at time of

death

14 National Vital Statistics Reports, Vol. 69, No. 2, January 30, 2020

was to see if the records would have some indication of a

pregnancy-related hospital encounter, including delivery, or that

a pregnancy would be noted in their record of care for a given

inpatient or emergency department visit. Pregnancy-related

hospital encounters were defined based on any diagnosis codes

using International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision or

10th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD–9–CM or ICD–10–CM)

or SNOMED for that encounter. If no indication of a pregnancy-

related diagnosis in the previous year was listed for these

decedents, then these records would be considered a potential

overuse of the pregnancy indication on the checkbox, or a

false positive use of the checkbox (i.e., the checkbox indicated

pregnancy when it should not have).

Underuse of the pregnancy indication on the checkbox

was assessed by first identifying all records of pregnancy-

related hospitalizations for persons who died within the year of

their hospitalization and then determining those records with

a pregnancy checkbox value of 1, 7, 8, or 9. Given that these

decedents had a record of a pregnancy-related hospitalization

in the previous year, the expectation is that the checkbox value

would indicate a current or recent pregnancy. Otherwise, if

no value indicating current or recent pregnancy existed in the

checkbox item, these records were considered an underuse of

the pregnancy indication of the checkbox, or a false negative

use of the checkbox (i.e., the checkbox should have indicated a

pregnancy when it did not).

The 2014 NHCS data were linked to the 2014–2015 NDI, and

2016 NHCS data were linked to the 2016–2017 NDI, to allow for an

assessment of mortality at intervals of interest (e.g., death at 30,

60, or 90 days postdischarge or 1-year survival postdischarge).

The linkage process has been detailed elsewhere: https://

www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/datalinkage/NHCS14_NDI14_15_

Methodology_Analytic_Consider.pdf and https://www.cdc.

gov/nchs/data/datalinkage/NHCS16_NDI16_17_Methodology_

Analytic_Consider.pdf.

Note that NHCS data for both 2014 and 2016 are based only

on the relatively small percentage of hospitals that responded to

the survey (16% in 2014 and 27% in 2016) and are not nationally

representative. Therefore, this case study is not intended to be

a nationally representative assessment of checkbox usage.

In addition, this analysis only includes visits that occurred at

sampled hospitals, and the possibility exists that the patient may

have been seen primarily at a nonsampled hospital during the year

before birth or that the mention of a pregnancy was omitted from

the record. Lastly, this analysis may miss cases of pregnancies

for which no event occurred necessitating a hospitalization or

emergency department visit (e.g., abortive outcomes).

Potential overuse of checkbox—false positives

To create the analytic sample to assess overuse of the

pregnancy checkbox, 150 women in the 2014 linked NHCS–NDI

and 220 women in the 2016 linked NHCS–NDI file were identified

with a checkbox value of 2, 3, or 4. In the 2014 NHCS, 81 of

the 150 decedents who were identified as pregnant within the

year before death by the checkbox (values 2, 3, or 4) had no

pregnancy-related hospital encounter within 1 year of death,

including no record of delivery. Of these 81 decedents, 32 were

under age 30, 15 were aged 30–39, and 34 were aged 40 and

over. Based on this analysis, 54% of records with a pregnancy

checkbox value indicating a current or recent pregnancy had no

pregnancy-related hospitalization nor any mention of pregnancy

in the hospitalization record in the previous year and were

considered false positives.

In the 2016 linked NHCS–NDI data, 124 of the 220 decedents

who were identified as pregnant within the year before death by

the pregnancy checkbox (values 2, 3, or 4) had no pregnancy-

related hospital encounter within 1 year of death. Of the 124

decedents, 47 were aged under 30, 36 were aged 30–39, and 41

were aged 40 and over. Based on this analysis, 56% of records

with a pregnancy checkbox value indicating a current or recent

pregnancy had no pregnancy-related hospitalization nor mention

of pregnancy in the record of hospitalization in the previous year

and were considered false positives.

Potential underuse of checkbox—false negatives

In the 2014 NHCS, 236 decedents with a pregnancy-related

hospitalization in the previous year were identified. Of these,

157 decedents had both a pregnancy-related hospital encounter

within 1 year of death and a pregnancy checkbox value of 1, 7, 8,

or 9 (not indicating pregnancy). Of the 157 decedents, 62 were

aged under 30, 62 were aged 30–39, and 33 were aged 40 and

over. Based on this analysis, 67% of 236 records of a pregnancy-

related hospitalization in the previous year did not have current

or recent pregnancy indicated by the pregnancy checkbox on the

death certificate and were considered false negatives.

In the 2016 NHCS, 253 decedents with a pregnancy-related

hospitalization in the previous year were identified. Of these,

158 had both a pregnancy-related encounter within 1 year of

death and a pregnancy checkbox value of 1, 7, 8, or 9. Of the

158 decedents, 64 were under age 30, 62 were aged 30–39, and

32 were aged 40 and over. Based on this analysis, 62% of 236

records with a pregnancy-related hospitalization in the previous

year did not have current or recent pregnancy indicated by the

pregnancy checkbox and were considered false negatives.

Summary

This analysis attempts to discern use of the pregnancy

checkbox from a data source linking hospitalization encounters

and deaths among patients. The purpose was to assess the use

of the checkbox according to whether a record of pregnancy in a

hospitalization event occurred in the period of time defined by the

checkbox (i.e., within 1 year). For both the 2014 and 2016 linked

files, approximately 53% of records were false positive cases of

pregnancy indication on the checkbox, while approximately 65%

of records were false negative cases of pregnancy indication

on the checkbox. The ability to examine use of the pregnancy

checkbox on the death certificate linked with hospitalization data

predating death provided a unique way to examine and highlight

potential misreporting of the checkbox, which may, in turn, affect

estimates of maternal mortality.

National Vital Statistics Reports, Vol. 69, No. 2, January 30, 2020 15

Late maternal deaths

Late maternal deaths (occurring between 43 days and 1 year

of death) are not included in the calculation of the official maternal

mortality rates, which are based on maternal deaths occurring

while pregnant or within 42 days of being pregnant. Late maternal

deaths are included in other maternal death measures, such as

in the calculation of pregnancy-related deaths, defined as the

death of a woman while pregnant or within 1 year of the end of a

pregnancy, as measured by the Centers for Disease Control and

Prevention’s Pregnancy Mortality Surveillance System (4). In the

National Vital Statistics System, identification of late maternal

deaths is similar to that for maternal deaths, in that the coding

procedures are based on causes of death reported on death

certificates and information on pregnancy status reported in the

checkbox item. Therefore, late maternal deaths are also affected

by the change in the coding methods.

Some late maternal deaths are identified via checkbox-only

records. In this situation, the checkbox is the only indication

of pregnancy, and the checkbox indicates that the pregnancy

occurred between 43 days and 1 year of death. In the 2018 coding

method, coding of late maternal deaths will restrict application of

the checkbox item to decedents aged 10–44 years. The checkbox

will not be applied in coding cause of death for decedents aged

45 and over. If the checkbox is the only indication of a pregnancy

for female decedents aged 10–44, a late maternal code will be

assigned as the underlying cause. However, a late maternal code

will be assigned only to the underlying cause and not to other

conditions reported on the certificate.

California data and coding methods

California has included a checkbox on the death certificate

since 2003, but it is not the one used on the U.S. Standard

Certificate of Death. The pregnancy checkbox used by California

asks only if a pregnancy occurred within the year of death and

does not differentiate timing of pregnancy. Under the 2003–2017

coding method, a positive response to this nonstandard category

without further specification of timing in the cause-of-death

statement was treated as if the pregnancy occurred between 43

days and 1 year before death (i.e., a late maternal death), and,

therefore, these deaths would not be coded as maternal deaths

or included in the calculation of the maternal mortality rate (10).

This could overestimate the number of deaths identified as late

maternal deaths and underestimate the maternal mortality rate

in California.

Application of the 2018 coding method will differ for

California compared with the rest of the jurisdictions. For

checkbox-only cases, no difference will exist between California

and the other states for women aged 45 and over, because these

cases will not be coded as maternal deaths under the 2018

coding rules. However, checkbox-only records in California

among women aged 10–44 will also not be coded as maternal

deaths, whereas they would be so coded in the other states where

the checkbox indicates a pregnancy before 43 days. Checkbox-

only deaths in California for those aged 10–44 will instead be

coded as late maternal deaths. For California and the rest of the

states, all deaths with cause-of-death information in addition to

the checkbox have the potential to be coded as maternal deaths

depending on the information included in the cause-of-death

section. The coding of the cause will follow usual coding and

use information from the checkbox, if available, to determine

timing. Quantifying the impact of coding all California checkbox-

only deaths as late maternal deaths on the maternal mortality

rate is difficult, but it is plausible that the national maternal

mortality rate may be somewhat underestimated. California will

begin using the standard checkbox in 2020, and changes in the

national maternal mortality rate as a result of this changeover

will be evaluated upon release of the 2020 data.

Race and Hispanic origin

The 2003 revision of the U.S. Standard Certificate of Death

allows the reporting of more than one race (multiple races), in

accordance with the revised standards issued by the Office of

Management and Budget in 1997. Information on this change

is presented elsewhere (17). The number of states reporting

multiple races increased over time, so that by midyear 2017,

all were reporting multiple races. To provide uniformity and

comparability of the data before all areas have data in multiple-

race format, the responses of those for whom more than one

race was reported (multiple races) were bridged to a single race.

The bridging procedure for multiple-race women is similar to the

procedure used to bridge the multiple-race population estimates.

Information detailing the processing and tabulation of data by

race is presented elsewhere (see https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/

data/dvs/Multiple_race_documentation_5-10-04.pdf).

Race and Hispanic origin are two distinct attributes and

are reported separately on the death certificate. Data shown for

Hispanic women include women of any race. Hispanic origin is

not imputed if it is not reported.

This report presents data by single-race group when only

one race was reported. A separate report (10) on maternal

mortality presented data for earlier years and showed data

by bridged race. The following Table is similar to Table 1 but

presents the information using bridged data.

Random variation

Mortality data are not subject to sampling error but may

be affected by random variation. That is, the number of deaths

that actually occurred may be considered as one of a large

series of possible results that could have arisen under the same

circumstances; see Technical Notes (17) for more complete