BPEA Conference Draft, March 28-29, 2024

Sustained Debt Reduction: The Jamaica Exception

Serkan Arslanalp (International Monetary Fund)

Barry Eichengreen (University of California, Berkeley)

Peter Blair Henry (Stanford University, Hoover Institution and Freeman Spogli Institute)

Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, Spring 2024 © 2024 The Brookings Institution

Conflict of Interest Disclosure: Henry is on the board of Citigroup. The International Monetary Fund

(IMF)'s Communications Department had the right to review this work prior to publication but did not inform the

findings. The authors did not receive financial support from any firm or person for this article or from any firm or

person with a financial or political interest in this article. Other than the aforementioned, the authors are not

currently an officer, director, or board member of any organization with a financial or political interest in this article.

The discussant, Laura Alfaro served as a consultant for the IMF Evaluation Office and a visiting scholar with

the Bank for International Settlements from 2023-24.

1

Sustained Debt Reduction: The Jamaica Exception

1

Serkan Arslanalp, Barry Eichengreen and Peter Blair Henry

March 2024

1. Introduction

Sharp, sustained reductions in public debt are exceptional, especially recently. We know

this because public-debt-to-GDP ratios have been trending up in advanced countries, emerging

markets, and developing countries alike. Governments have borrowed in response to financial

crises, pandemics, wars and other emergencies, resulting in higher debt ratios. But only in rare

instances have they succeeded in bringing those higher debt ratios back down once the

emergency passed.

Both economic and political factors underlie this inability to reduce debt ratios. Slowing

GDP growth and rising real interest rates (an unfavorable r-g differential in the economist’s

parlance) make for adverse debt dynamics. Ideological polarization and frequent government

turnover make it hard to stay the course. Turnover creates an opportunity for a new

administration to repudiate the policies of its predecessor, disrupting efforts to sustain substantial

primary budget surpluses. Polarization makes it hard to agree on how to share the burden of

fiscal adjustment, fraying the coalition favoring debt reduction and causing policies to be

reversed.

2

These economics and politics leave one pessimistic about the prospects for sustained debt

reduction. Against this gloomy backdrop, it is uplifting to consider cases where countries have

succeeded in significantly reducing their debt ratios. In addition to their morale-building effect,

such cases may help to illuminate the economic and political conditions that facilitate debt

consolidation.

Jamaica is such a case. The government reduced its debt from 144 percent of GDP at the

end of 2012 to 72 percent in 2023.

3

Jamaica cut its debt ratio in half despite averaging annual

real growth of only ¾ percent over the period. It did so despite vulnerability to hurricanes,

floods, droughts, earthquakes, storm surges and landslides: Jamaica is ranked as the third most

disaster-prone country in the world according to the Global Facility for Disaster Reduction and

Recovery. It did so despite a COVID-19 pandemic that disrupted tourism and mandated

exceptional increases in public spending. Yet, despite this exogenously prompted deviation from

1

Prepared for the Brookings Panel, March 28-29, 2024. We thank Eleanor Brown, Patrick Honohan, Tracy

Robinson, Jón Steinsson, DeLisle Worrell, and Karina Garcia, Thomas Pihl Gade, Vitor Gaspar, Jan Kees Martijn,

Pablo Morra, Constant Lonkeng Ngouana, Uma Ramakrishnan, Bert van Selm, Esteban Vesperoni (all IMF) for

helpful discussions. Views are the authors’ and do not necessarily represent those of the IMF, its Executive Board,

or IMF management.

2

Alesina and Tabellini (1990) provide a formal framework where polarization leads to overspending and debt

increases, consistent with our presumption. Admittedly, there are also other theoretical models, based on somewhat

different assumptions, that point to somewhat different effects.

3

All figures for Jamaica are in fiscal years, which run from April 1 to March 31 of the following year.

2

plan, the IMF’s baseline projection, in its 2023 Article IV report, forecasts a further fall in

debt/GDP to less than 60 percent over the next four years.

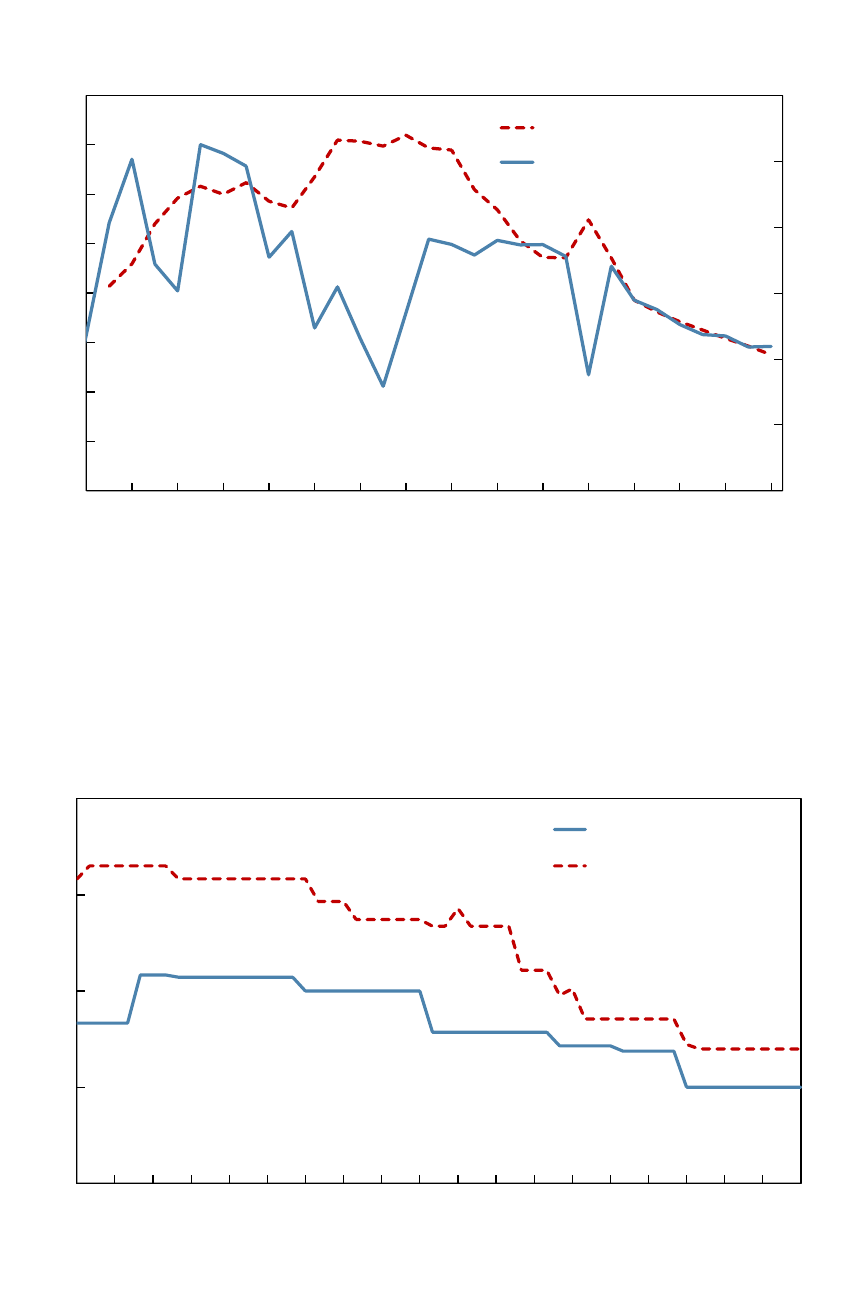

Figure 1 shows Jamaica’s achievement. It suggests that 2013 was a breakpoint, when the

debt ratio began its decline. Table 1 underscores the exceptional nature of the experience. Using

a broad group of emerging markets and developing economies, it tabulates cases since 2000

where debt ratios fell by as much as 20, 30, or 40 percent of GDP over a five-year period.

Jamaica has few peers.

Figure 1 also points to the central economic mechanism responsible for the reduction in

the debt ratio. The Government of Jamaica ran large, sustained primary budget surpluses.

4

Table 1 shows how unusual this is: of the debt reduction episodes we identify since the turn of

the century, just 5 relied principally on primary surpluses.

The question is how Jamaica accomplished this. Our answer consists of two parts. First,

Jamaica adopted fiscal rules that highlighted the debt problem, encouraged formulation of a

medium-term plan, and limited fiscal slippage. The Fiscal Responsibility Framework introduced

in 2010 required the Minister of Finance to take measures to reduce, by the end of fiscal year

2016, the fiscal balance to nil, the debt/GDP ratio to 100 percent, and public-sector wages as a

share of GDP to 9 percent. The framework was augmented in 2014 to require the minister, by

the end of fiscal year 2018, to specify a multi-year fiscal trajectory to bring the debt/GDP ratio

down to 60 percent by 2026. The framework included an escape clause to be invoked in the

event of large shocks. This prevented the rule from being so rigid, in a volatile macroeconomic

environment, as to lack credibility. At the same time, it included clear criteria and independent

oversight to prevent opportunistic use.

Fiscal rules and targets do not always achieve their intended results. A quick look at the

European Union’s Stability and Growth Pact, which similarly targets a 60 percent debt-to-GDP

ratio, provides a stark reminder of this fact. This brings us to the second part of our answer:

elected officials leveraged Jamaica’s hard-won tradition of consensus building – of constructing

over the course of 30 years social partnerships aimed at facilitating dialogue, limiting political

instability, and reducing political polarization and violence (see Figure 2). In 2013, a series of

ongoing discussions in the National Partnership Council, a social dialogue collaboration

involving the government, parliamentary opposition, and social partners, culminated in the

Partnership for Jamaica Agreement on consensus policies in four areas, first of which was fiscal

reform and consolidation. The Partnership for Jamaica Agreement fostered a common belief that

the burden of fiscal adjustment would be widely and fairly shared. It supported the creation and

ensured broad national acceptance of the Economic Programme Oversight Committee (EPOC) to

monitor and publicly report on fiscal policies and outcomes, and to provide independent

verification that all parties kept to the terms of their agreement.

EPOC and the Partnership for Jamaica Agreement solidified the sharp decline in

conventional measures of political polarization that began four years earlier, coincident with the

4

Other factors, from real exchange rate stability and banking-system stability to bits of clever financial management

(e.g., a domestic debt exchange in 2013, the PETROCARIBE debt buyback in 2015), also contributed to this

process. We discuss these below.

3

creation of the National Partnership Council (see Table 2).

5

A sustained lower level of

polarization made for policy continuity and continued debt reduction when a different political

party took power in 2016. For the first time in decades, a new government did not reverse the

policies of its predecessor. By creating a sense of fair burden sharing, Jamaica’s organized

process of consultation thus sustained public support for the operation of the country’s fiscal

rules, culminating in March 2023 with the establishment of a permanent, independent Fiscal

Commission.

As always, the full story is more complex. Jamaica managed its financial system well in

this period. It adeptly managed the term structure of the debt, as we describe below. But the two

elements highlighted above – a well-designed fiscal rule, and a partnership agreement creating

confidence that the burden of adjustment would be widely and fairly shared – were key. Neither

element would have worked to achieve sustained debt reduction in the absence of the other.

Both were needed.

An important question is whether the lessons from Jamaica generalize. In Section 5 we

discuss two other countries that achieved significant debt reduction by adopting fiscal rules and

consensus-building arrangements: Ireland in the late 1980s and Barbados for a decade starting in

the early 1990s. These cases differ in their particulars. But they have in common that Ireland

and Barbados – like Jamaica – are small, open economies. These economies are highly

structured, in that trade unions and employers associations are cohesive and powerful. In both

cases, the agreements reached and institutions created to initiate and maintain the momentum of

debt reduction leveraged earlier historical experience with institution-based consensus building.

The similarities of these cases are consistent with the literature suggesting that

democratic corporatism, a process of policy formulation involving extensive consultation and

consensus building, is easiest where interest groups are well organized and the number of agents

is limited.

6

They are consistent with the view that such arrangements are imperative in small,

open economies especially exposed to exogenous shocks. And they are consistent with the view

that so-called neocorporatist arrangements, when and where they emerge, build on earlier

historical experience.

A clarification before proceeding. Our paper is about debt reduction; it is not about fiscal

consolidation, where the latter connotes episodes where governments move from large budget

deficits to smaller deficits or surpluses. There is a substantial literature on fiscal consolidations,

5

We acknowledge that cause and effect are difficult to disentangle in this context. It is reasonable to believe that

causality ran both ways. We return to this issue in Section 4D below.

6

Peter Katzenstein, who is prominent in defining and popularizing the concept of democratic corporatism, defines

it as a political system characterized by “an ideology of social partnership, a centralized and concentrated system of

economic interest groups, and an uninterrupted process of bargaining among all of the major political actors across

different sectors of policy” (Katzenstein (1985, p.80). Although Katzenstein applied these ideas to countries’

response to international competitive pressures, not so much to debt problems, we build on his insights. We are not

arguing that democratic corporatism is the only setting in which significant debt reduction can occur. One can think

of authoritarian settings where high debts were dramatically reduced; Romania under Nicolae Ceauşescu springs to

mind (not that this turned out well for the Ceauşescus). 2 of the 14 cases in Table 1 have a rating of 0.4 or below on

the Polity Scale, situating them on the autocratic side of the autocracy-democracy continuum. Others have relatively

high levels of political polarization but were able to reduce high levels of debt through other means (high inflation

financial repression, or more positively faster economic growth). But to reiterate, our goal here is not to determine

whether democracy or autocracy is “better” for debt reduction, or whether low levels of political polarization are

always and everywhere a prerequisite for significant debt reduction. It is simply to understand how Jamaica did it.

4

including in this journal (Alesina, Perotti and Tavares 1998). To be sure, the two concepts are

related. In Jamaica, however, the primary surplus already was large before the process of debt

reduction began (more than 7 percent of GDP in 2012, as in Figure 1). The surplus remained

broadly unchanged thereafter and then became smaller, as appropriate for a country with lower

debt. We are not studying a change in the stance of fiscal policy starting in 2013; we are focused

instead on understanding a decade and more of debt reduction sustained by large, persistent

primary surpluses.

7

2. Historical Background

Jamaica’s recent experience of debt reduction is exceptional, but the country’s earlier

history was also marked by exceptional fiscal developments, some positive, others not. The

1962 constitution included a provision prohibiting the government from borrowing without

parliamentary approval. It prioritized servicing the debt as an obligation senior to other

government expenses (Langrin 2013). Accordingly, Jamaica has never had an outright default

on its sovereign debt, although it has conducted domestic debt exchanges (described below). .

Fiscal restraint was designed to attract the foreign direct investment (FDI) needed for

development of the capital-intensive bauxite industry. True to form, FDI financed 30 percent of

all capital formation in the 1960s and virtually all investment was in the bauxite sector.

Public debt remained modest in the first post-independence decade, reflecting the

consensus around these priorities. The ruling Jamaica Labour Party (JLP) eschewed activist

fiscal and monetary policies, relying on tax breaks and free profit repatriation to attract foreign

investment.

8

Jamaica successfully grew the denominator of the debt-to-GDP ratio: real GDP

rose by roughly 6 percent per annum in what Stone and Wellisz (1993) called “one of the best

growth records in the world.” Mining was relatively unimportant in the 1950s, and tourism had

contributed only modestly to economic activity; this meant that there was low-hanging fruit to be

picked. King (2001, p.7) describes growth in this period as built on “natural endowments of

bauxite and beaches.”

Capital-intensive mining created little employment, however, while Dutch Disease

pressures led to declines in the relative importance of agriculture, forestry, and fishing. Small-

scale manufacturing and services had limited capacity to absorb surplus labor released by the

rural sector, given the floor placed on wages by strong unions and insider-outsider dynamics.

By the time of the 1972 election, unemployment, mostly urban, had risen to more than 20

percent, and dissatisfaction with education and health-care services was rife. These grievances

led to a backlash against the JLP’s cautious policies, culminating in the electoral victory of the

People’s National Party (PNP) led by the charismatic Michael Manley. The approach of the new

PNP government was variously labelled “state populism” (King 2001) and “democratic

socialism” (Stephens and Stephens 1986).

9

The PNP nationalized companies, raised import

barriers, and imposed exchange controls; spending on schooling, food subsidies and public

housing exploded (Henry 2013, Chapter 2). Public employment rose by two-thirds between

7

As also highlighted by IMF (2023).

8

Thus, fiscal deficits averaged a relatively modest 2.3 percent of GDP from 1962 through 1972 (Henry and Miller

2009), while the currency was pegged to the pound sterling under a quasi-currency board system. Jamaica switched

from a sterling peg to a dollar peg in 1973, following the change in government (which reinforced the peg with

capital controls – more on which below), the U.S. by this time having become the country’s leading trade partner.

9

The party used the latter term in its election manifestos.

5

1972 and 1977, while public spending as a share of GDP doubled from 23 percent to 45 percent.

The budget deficit averaged 15 percent of GDP. The government financed what it could by

borrowing, mainly abroad, and the Bank of Jamaica financed the rest. The debt/GDP ratio

soared from 24 percent at the time of the 1972 election to 124 percent in 1980 (Figure 3).

Inflation, having averaged 4 percent in the first post-independence decade, reached 27 percent in

1980.

The PNP’s focus on social justice notwithstanding, its policies were economically

disastrous. Dirigiste rhetoric and policies of nationalization discouraged investment. Labor

productivity and real wages slumped, and unemployment rose to 30 percent. As standards of

living continued to fall, the implications for survival of the zero-sum patronage gained or lost

with each election rose higher, and political violence spiked (Figure 2). This economic and

political chaos led, predictably, to the PNP’s defeat in the 1980 election, the return of the JLP,

and a swing back toward more market-oriented policies.

When the decline in foreign investment and macroeconomic stimulus created balance-of-

payments problems in 1977-78, the PNP was forced to negotiate agreements with the IMF. Both

programs were then suspended when the government failed to meet performance targets. (Figure

4 shows a timeline of the country’s agreements with the Fund.) The JLP government tried again

in 1980: it devalued to improve export competitiveness, cut government spending, eliminated

price controls, and negotiated new loans with the IMF and World Bank (Kirton 1992). Its

policies were contractionary in the short run, provoking violent demonstrations, but by the mid-

1980s productivity and GDP began rising again.

Jamaica’s first episode of concerted debt reduction began in the second half of the 1980s.

Debt had risen to an extraordinarily high 240 percent of GDP, requiring urgent action. The JLP

imposed spending cuts, moving the primary balance into surplus. Progress was interrupted in

1988-9 by Hurricane Gilbert, which destroyed more than 100,000 homes, but even this did not

throw the process off course. Importantly, when the PNP returned to power in 1989, it

maintained the same basic economic stance. Chastened by its earlier experience of deficits and

negative growth, it restrained public spending, raised taxes, and restricted credit, allowing

primary surpluses to be maintained. There was now more dialogue between the parties as their

policy differences grew less pronounced. Figure 2 shows the measure of political polarization

from the Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) data base; this is based on responses to a survey of

country experts conducted each year.

10

The figure documents a fall in polarization at the

beginning of the 1990s, the largest fall since independence, exceeding even the sharp fall in

polarization two decades later. This was then followed by a steep decline in political violence

10

V-Dem typically takes input from at least five experts for each country and year, drawing on some 3,700 experts

worldwide. For political polarization, it asks: “Is society polarized into antagonistic, political camps?” Responses

range from: 0 (Not at all. Supporters of opposing political camps generally interact in a friendly manner); 1 (Mainly

not. Supporters of opposing political camps are more likely to interact in a friendly than a hostile manner); 2

(Somewhat. Supporters of opposing political camps are equally likely to interact in a friendly or hostile manner); 3

(Yes, to noticeable extent. Supporters of opposing political camps are more likely to interact in a hostile than

friendly manner); and 4 (Yes, to a large extent. Supporters of opposing political camps generally interact in a hostile

manner). For political violence, it asks: “How often have non-state actors used political violence against persons this

year?” Responses range from: 0 (Not at all. Non-state actors did not use political violence); 1 (Rare. Non-state

actors rarely used political violence); 2 (Occasionally. Non-state actors occasionally used political violence); 3

(Frequently. Non-state actors frequently used political violence); and 4 (Often. Non-state actors often used political

violence). See V-Dem Dataset Codebook (2023).

6

from the mid-1990s to early 2000s (also shown in Figure 2). This experience thus shows how

cross-party agreement on basic economic priorities is important for debt reduction.

This is the positive part of the story. The negative part is inflation, which was the single

most important contributor to debt reduction in the decade ending in 1995. End-of-fiscal-year

inflation accelerated to 28 percent in 1990, 106 percent in 1991, and 21 percent againin 1992.

Given that some 60 percent of local government debt was held in medium- to long-term

securities, this brought the debt ratio down very sharply, from 175 percent of GDP at the end of

1990 to 100 percent at the end of 1991, for example.

But this route to debt reduction was unsustainable because it undermined the foundations

of the financial system. Inflation reflected measures taken by Jamaican authorities to liberalize

the financial system, without at the same time strengthening financial supervision. In the run-up

to the crisis, they removed ceilings on credit provided by banks, deregulated deposit rates,

encouraging banks to compete for funding, and permitted banks to make U.S. dollar-

denominated loans.

11

Unfortunately, even while Jamaica began easing restrictions on capital

account transactions, it retained a patchwork of financial regulators and regulations, creating

scope for regulatory arbitrage given the weak supervisory capacity of the central bank. The

authorities liberalized the capital account in the hope that this would lead to capital inflows,

reduce depreciation pressure on the exchange rate, and mitigate inflation. This was also a period

when the IMF was advising its emerging market members to liberalize the capital account, and

Jamaica, continuously under IMF programs, acted accordingly.

12

The result was a very large capital inflow as exchange controls were relaxed, funding

additional domestic lending as investors repatriated offshore dollars. The removal of

quantitative credit ceilings permitted the development of an enormous credit boom; bank credit

to the private sector grew at double-digit rates, always a warning sign; hence the surge of

inflation.

13

The credit boom was characterized by deteriorating asset quality, declining bank

profits, and a growing currency mismatch as banks extended U.S. dollar loans to firms in the

nontraded goods sector where revenues accrued in local currency.

Initially, the implications for the debt/GDP ratio were favorable, as the credit-fueled burst

of inflation led to a negative real-interest-rate-real-growth-rate differential (Figure 5). But those

favorable dynamics did not last. In mid-1995, the Bank of Jamaica finally got serious about

inflation and tightened monetary policy. Higher interest rates led to weakness in the real estate

sector, to which financial institutions were predictably committed. This raised questions about

bank solvency, precipitating withdrawals by panicked depositors.

14

A massive financial crisis

11

Kirpatrick and Tennant (2002), p.1935. There had in fact been an earlier attempt to liberalize the banking system

in the mid-to-late 1980s as a condition of the country’s World Bank program, but this was reversed in 1989 when

Hurricane Gilbert prompted sharp increases in government spending, which the fiscal authorities enlisted the banks

to finance. Another factor prompting reregulation was a massive inflows of reinsurance funds, leading to increased

bank liquidity and what was perceived as an unsustainable surge in lending (Peart 1995).

12

Jamaica had begun dismantling exchange controls in 1990 and formally abolished all remaining capital controls in

1991-92 (again see Kirkpatrick and Tennant 2002).

13

World Bank (2004), p.25.

14

Newly deregulated life insurance companies aggressively marketed short-term products offering high rates of

return and invested these short-term funds in long-term, illiquid assets, mainly real estate. Scenting an opportunity,

banks for their part extended high-interest-rate loans to insurance companies with which they were connected,

causing the banking system to be implicated. This is a clear instance of the regulatory arbitrage noted above.

7

engulfed commercial banks, investment banks, building societies, insurance companies and

security brokers in the mid-1990s. Laeven and Valencia (2020) rank this as the third most costly

banking crisis anywhere in the world in the five decades after 1970.

15

Starting in 1996, GDP fell for three consecutive years. With nonperforming loans as a

share of total loans rising to nearly 30 percent, the financial system had to be recapitalized by a

newly created special purpose vehicle, the Financial Sector Adjustment Company, whose

liabilities were ultimately transferred to the government’s balance sheet. Effectively, the

government replaced nonperforming loans with government debt in an effort to reassure

depositors.

Given a fiscal cost of 44 percent of GDP and falling revenues owing to the crisis-induced

recession, it is no surprise that this mega-financial crisis threw debt reduction off course. After

falling steadily for more than a decade, the debt ratio now rose sharply. This episode is a

reminder that financial stability is essential for sustained debt reduction, and that a burst of

inflation, even if helpful for debt reduction in the short run, is not compatible with such stability.

The debt ratio continued rising through the first decade of the new century, from roughly

100 percent of GDP at the outset of the decade to 140 percent at decade’s end. It did so even

once the government resumed running primary budget surpluses, as it had before the banking

crisis.

16

This suggests that the cross-party consensus favoring fiscal rectitude was alive, but that

Jamaica was experiencing an unfavorable r-g differential, reflecting anemic growth that rarely

exceeded 1½ percent together with stubbornly high nominal interest rates in the range of 15

percent.

The root causes of this slow growth were several. Jamaica lacked affordable energy to

profitably refine bauxite into aluminum and the inexpensive labor needed to compete with its

lower-cost Caribbean and Central American neighbors. Infrastructure, education, and training

remained deficient (Henry 2023).

17

High real interest rates reflected chronic doubts about the

government’s willingness and ability to control inflation and service its debts. Given an

unfavorable r-g and high inherited debt, the World Bank in 2004 calculated that the government

would have to run primary surpluses of 10 percent of GDP just to prevent the already sky-high

debt ratio from rising further. Given these formidable headwinds, little progress was made on

the debt front for the remainder of the decade.

3. What Jamaica Did

This unpropitious backdrop renders what happened next all the more remarkable. As

shown in Figure 1, the public debt/GDP ratio stopped rising in 2010 and, after a few years, began

falling precipitously. From a peak of 144 percent in 2012, it declined to just 72 percent in 2023.

The IMF expects that debt ratio to decline still further, to below 60 percent four years from now.

By emerging market standards, this achievement is exceptional (in several senses of the

word). We first analyze how this debt reduction was achieved in an accounting sense before

15

This crisis was exceeded in cost only by Indonesia in 1997 and Argentina in 1980.

16

Recall that we noted in the introduction how this distinguishes the present analysis of debt reduction from the

literature on budgetary adjustment or fiscal consolidation.

17

In addition, the global economic crisis of 2008-9 hit an economy reliant on bauxite exports, tourism, and

remittances with exceptional force. This is evident in the collapse of r-g in Figure 5.

8

asking how it was achieved in an economic and political sense. To this end, Figure 6 shows the

standard debt decomposition:

∆ = +

( − )

1+

−1

+ (1)

where b is debt as a share of GDP and ∆ is its change. The right-hand side is made up of the

primary budget deficit (net of interest payments) relative to GDP, denoted d; r-g interacted with

the inherited debt ratio; and the residual, which captures defaults, restructurings, conversions,

assumption by the public sector of private debt, other off-budget spending, and exchange rate

effects, collectively denoted sfa (stock-flow adjustment).

Figure 6 shows that debt reduction was driven mainly by primary budget surpluses,

which are large throughout the period, falling to low levels solely in 2020, the first year of

COVID. The government maintained these primary surpluses despite strongly increasing non-

interest spending, from 19 percent of GDP in 2014 to 23 percent of GDP in 2019, on the eve of

the COVID crisis.

18

In other words, surpluses were sustained by strongly increasing tax

revenues as a share of GDP. Most of the gains in tax revenue resulted from broadening the base

(removing tax exemptions). In addition, there was an increase in the general consumption tax

and an increase in the personal income tax rate for high earners from 25 to 30 percent (the latter

in fiscal year 2016), accompanied by improvements in tax administration. This is a reminder

that we are not telling the standard tale of fiscal consolidation where deficit gives way to surplus,

typically through a one-time reduction in public spending.

19

In addition, there is a modest contribution from GDP growth, mainly toward the end of

the period, modest because growth remained anemic by emerging market standards. This is

reminder that sound debt management by itself is no guarantee of positive growth performance –

and, conversely, that strong growth is not always and everywhere a prerequisite for successful

debt reduction.

20

There is also a contribution to debt reduction from the negative real interest

rate, reflecting high inflation in the immediate post-COVID period.

21

Figure 6 highlights several years early in the period in which there were increases in the

debt burden due to factors not otherwise explained. These increases reflect the materialization of

contingent liabilities stemming from unexpected losses by public enterprises such as Clarendon

Alumina Production (CAP) and Jamaica Urban Transit Co. In fiscal year 2012, for example, the

18

There was some reduction in public spending as a share of GDP from 2012 through 2014, but this was swamped

by the increase in the public expenditure ratio in the period that followed. Note that we are referring to non-interest

expenditure, since this is what matters for the primary balance.

19

There is debate in the literature about whether deficit reduction achieved through cuts in spending rather than

through increases in taxes are more likely to be sustained or are more conducive to economic growth (see e.g.,

Alesina and Ardagna 2010, 2013 and Alesina et al. (2019)). Although we find a different pattern in the data for

Jamaica, we are not concerned with this debate directly, since we are addressing a different question.

20

Growth was at or near the average for Caribbean economies. Such growth as occurred came mainly from a

decline in the unemployment rate, which fell steadily over the period, not from productivity growth (see Henry

2023). All this reinforces our point that the exceptional decline in the debt ratio is not attributable to exceptional

growth performance.

21

Otherwise, real interest rates are modestly positive on average (Figure 5), roughly offsetting the contribution of

real GDP growth (Figure 6). There is a sharp fall in both inflation and nominal interest rates on government debt in

2014, leaving the real interest rate essentially unchanged.

9

government was forced to assume 70 percent of the liabilities of CAP.

22

The prevalence of such

problems was then reduced in the period’s second half by strengthened governance of public

enterprises.

23

Meanwhile stronger financial supervision and regulation helped to avoid losses

from the kind of banking crisis that had thrown 1990s debt-reduction efforts off course.

Figure 7 sheds more light on what lies behind the debt decomposition. Here we further

decompose the change in the debt/GDP ratio as follows:

∆ = +

( − )

1+

−1

+

(1+)(1+∗)

−1

+

(−∗)

(1+)(1+)(1+∗)

−1

+ (2)

where r = the real interest rate; p = growth rate of GDP deflator; p* = growth rate of U.S. GDP

deflator; g = real GDP growth rate; a = share of foreign-currency denominated debt; z = real

exchange rate depreciation (measured as [(e

/e

−1

) (1 + p*) / (1 + p)] - 1) and e = nominal

exchange rate (measured by the local currency value of U.S. dollar).

24

The exchange rate

matters because more than a quarter of debt at the beginning of the debt reduction period was

denominated in or indexed to dollars. Comparing Figures 6 and 7, we can see how limited but

ongoing depreciation of the Jamaican dollar increased the domestic-currency value of external

debt.

Relatedly, Figure 8 shows how the foreign-currency share of the debt rose as debt

reduction allowed Jamaica to resume tapping international financial markets in 2014. It didn’t

hurt that this was a period of low interest rates in advanced countries, encouraging international

investors to search for yield in emerging markets. While a limited number of relatively large

middle-income countries were able to place domestic-currency debt with international investors

over this period (freeing themselves of the “original sin” of foreign-currency-denominated

external debt), Jamaica was not one of these.

25

The country’s increasing reliance on foreign currency debt was not overly detrimental.

Figure 7 shows why: although there was a contribution to the debt from exchange rate

depreciation, the real exchange rate was reasonably stable against the U.S. dollar (that is, the

nominal exchange rate moved broadly in line with the inflation differential vis-a-vis the United

22

IMF (2018), p.44.

23

Jamaica Urban Transport remains government owned and operated. The government agreed to privatize

Clarendon Alumina Production as a condition of its subsequent programs with the IMF, and in 2020 merged its

holdings with those of General Alumina Jamaica, which is owned and operated by the Hong-Kong based Noble

Group; 55 percent of the merged entity was owned by Noble Group, 45 percent by the government of Jamaica.

24

See IMF (2022, Box 3) for the derivation.

25

Arslanalp and Eichengreen (2023) show how success at placing domestic-currency-denominated securities with

international investors in this period was largely limited to a handful of relatively large emerging markets

economies. In November 2023, Jamaica issued its first-ever Jamaican dollar-linked bond in international capital

markets, “with the objective of opening local currency debt issues to international investors” (Ministry of Finance

and the Public Service 2023). Jamaica-dollar linked means that while the issue is denominated in Jamaican dollars,

debt service payments are in U.S. dollars at a rate determined by the average of the prevailing Jamaican dollar

exchange rate over the 10 days prior to each payment. Jamaica used the proceeds to buy back outstanding U.S.

dollar-denominated bonds, which Moody’s commented would reduce “the government’s exposure to foreign

exchange risk, which is a credit positive” (Ibid).

10

States). This is a reminder of the value of a relatively stable real exchange rate for debt

reduction, especially when a portion of that debt is denominated in foreign currency.

26

Comparing Figures 6 and 7, we see that separating out the impact of exchange-rate

depreciation on the value of external debt turns the overall contribution of the sfa from positive

(adding to the debt burden) to negative (subtracting from the debt burden).

27

This makes it

tempting to look to the pair of domestic debt restructurings conducted in 2010 and 2013. In fact,

these operations had a limited impact on the debt burden. Neither entailed nominal haircuts

reducing the face value of the debt, partly because a non-negligible fraction of that debt was held

by domestic financial institutions (Figure 9) whose stability would have been jeopardized

(Schmid 2016). External debt was excluded because Jamaica’s global bonds lacked majority

action clauses, threatening litigation and inconclusive negotiations with holdout creditors.

28

Still, these exchanges helped on the budgetary front, despite the absence of face-value

haircuts, by reducing coupons and extending maturities. In both cases, the government

succeeded in achieving very close to 100 percent investor participation. Here the same factor

that prevented face-value haircuts, that domestic debt was held mainly by a handful of financial

institutions, helped by attenuating free-rider problems.

29

This observation has implications for

whether the lessons from Jamaica carry over to other countries, since in quite a few other

countries debt securities are not in the hands of domestic banks but are widely held by

heterogeneous creditors whose coordination is difficult to achieve.

In sum, the Jamaican authorities mainly reduced their debt “the old-fashioned way,” by

running substantial primary budget surpluses for an extended period. To be sure, they also grew

26

This is not to recommend issuing debt in foreign currency so as to take advantage of relatively low international

interest rates. The risks are well known. The strategy worked in Jamaica because the authorities succeeded in

limiting real depreciation of the local currency. The credibility of Jamaica’s policies, discussed further below, may

help to explain the stability of the currency in the face of global shocks. So too may an element of luck.

27

Figures 6 and 7 show that at least as important quantitatively as the 2013 debt exchange were a pair of financial

operations undertaken in 2015 and 2016. The 2015 residual reflects a buyback at a substantial discount of the

government’s Petrocaribe debt. Jamaica incurred this debt in return for purchases of oil from the Venezuelan state-

owned oil company PDVSA. In 2015 the government bought back this debt, raising cash for the operation by

issuing a 13-year Eurodollar bond. The buyback replaced debt to Venezuela with new external debt bearing a

significantly lower face value but a higher interest rate. The net effect was to push a portion of the financial burden

out into the future, creating a 10 percent of GDP reduction in measured debt in 2015. See Okwuokei and van Selm

(2017). The 2016 residual reflects an accounting adjustment implemented in conjunction with the new Fiscal

Responsibility Law described below, that excluded intra-governmental debt holdings and Bank of Jamaica’s

external debt (offset by the central bank’s external reserves), in line with international statistical standards. In any

case, these operations made only a limited contribution to the reduction in debt over the period.

28

Such clauses allow a qualified majority of creditors to cram down restructuring terms on a dissenting minority.

The exclusion of external debt from restructuring was a factor in the government’s ability to tap the Eurodollar

market in 2014 and 2015 and buy back the Petrocaribe bonds, as described in the preceding footnote. In addition,

the constitutional priority attached to servicing external debt (we described in Section 2 above how this provision

was put in place in the 1960s to help attract FDI) may have contributed to the difficulty restructuring.

29

Thus, the government could coordinate its negotiations with this limited number of financial institutions over

which it had regulatory oversight and leverage. As an inducement, financial institutions that participated were

offered preferential access to a Financial Sector Support Fund administered by the central bank. Participants in the

2010 debt exchange had the option of new series that were CPI indexed and non-callable, features not included in

the old bonds. In the 2013 exchange, large institutional investors that initially held out were subjected to political

pressure (they were criticized as “unpatriotic”), while small retail investors who might have held out from a second

restructuring that further lengthened maturities were offered special one-year bonds. See Langrin (2013).

11

the economy, if modestly, while eschewing excessive currency depreciation that might have

elevated the domestic-currency value of external debt. They avoided financial instability that

had caused the materialization of contingent liabilities and derailed earlier efforts at debt

reduction. They engaged in some clever financial management.

30

But budget surpluses were

key.

This strategy of running substantial primary budget surpluses for extended periods is not

commonplace; other emerging markets, developing countries, and advanced economies would be

envious. The question is how Jamaica did it.

4. How Jamaica Did It

Our explanation of how Jamaica did it consists of two parts. First, Parliament passed a

set of rules known as the Fiscal Responsibility Framework.

31

These rules highlighted the debt

problem, legislated formulation of a medium-term plan, and made it easier to define and detect

fiscal slippage.

All too often, however, rules are honored in the breach. This brings us to the second

element: Jamaica leveraged its hard-won tradition of forging social partnerships to establish

consultative bodies with the legitimacy, independence, and stature needed to build and sustain a

social consensus for fiscal adjustment, while credibly monitoring and reporting on the

government’s adherence to its fiscal rules and the progress of the overall economic reform

program. In 2009, government, the opposition, business, trade unions, and civil society groups

formed a consultative body called the National Partnership Council to address the effects of the

Global Financial Crisis, as well as longstanding economic and social issues. Deliberations of this

council enabled stakeholders to exchange views, provide input, reach consensus about the

societal importance of debt reduction, and assure all partners that the burden of adjustment

would be broadly and fairly shared. In ongoing meetings, its members discussed the conformity

of policies with their shared priorities and suggested changes to align policies and priorities more

closely. The Fiscal Responsibility Framework we discuss in the next subsection can be seen as a

legislative response to the broad societal consensus for fiscal restraint built by the National

Partnership Council. It then became possible to move from vision to reality when the Economic

Programme Oversight Committee (EPOC) was created in 2013. EPOC consists of

representatives of the private and public sectors, unions, and civil society but with

disproportionate representation of the financial sector. It is tasked specifically with monitoring

the government’s progress and benchmarking this against the performance targets of the Fiscal

Responsibility Framework.

This monitoring, dialogue, and consensus building were pivotal for holding government

accountable for its budgetary actions and for maintaining the consensus needed to get the process

on track and keep it there.

4A. Fiscal Rules

30

This refers to the buyback of Petrocaribe debt describes in footnote 27.

31

Jamaica is unusual in this regard; it is one of only two Caribbean Community (CARICOM) countries, along with

Grenada, to have adopted an explicit national fiscal rule. Grenada’s national budget balance, debt and expenditure

rules date from 2015 – that is, they post-date Jamaica’s fiscal rule.

12

Prior to 2010, when the Fiscal Responsibility Framework was put in place, Jamaica’s best

laid fiscal plans repeatedly went off course. Recorded deficits exceeded those in the budget

passed by Parliament in every year between 2003 and 2009 (Leon and Smith 2012, pp.13-14).

Growth forecasts were excessively rosy. Tax revenues regularly fell short of projections.

Expenditure overshot what was budgeted; in particular, public-sector wage settlements regularly

exceeded what was assumed by the Ministry of Finance. Public bodies such as the Urban

Development Corporation and the Bauxite Aluminum Trading Company, of which there were

more than 200, did not regularly report to the Ministry of Finance. For its part, the Ministry did

not update cash flow forecasts and performance for these entities in-year, unlike for the central

government. Lack of updating permitted chronic overspending and the accumulation of arrears

by these public bodies. Moreover, the central government conducted budgeting on a year-by-

year basis; “the future implications of expenditure decisions [were] not elaborated on in the

budget documents …consideration is not always given for the medium/long-term implications of

decisions made in the short-term” (Ibid). Though the Ministry of Finance was responsible for

describing its debt management strategy in broad terms, it was not required to formulate and

present a debt sustainability analysis.

The 2010 Fiscal Responsibility Framework, formally an amendment to existing Financial

Administration and Audit Regulations, addressed most of these shortcomings.

32

It anchored

budgeting by requiring the Minister of Finance to take appropriate measures to reduce, by the

end of fiscal year 2016: (a) the fiscal balance to nil; (b) the ratio of debt/GDP to 100 percent; and

(c) public-sector wages as a share of GDP to 9 percent (Jamaica House of Parliament 2010, p.

6).

33

The Framework was tightened in 2014 to require the Minister, by the end of fiscal year

2018, to specify a multi-year fiscal trajectory bringing the debt/GDP ratio down to no more than

60 percent by fiscal year 2026 (Jamaica House of Parliament 2014, p. 10).

34

Importantly, these numerical targets for debts and deficits came with an escape clause to

be invoked in exceptional circumstances. Rigid targets would have lacked credibility in an

environment prone to hurricanes, floods, and other natural disasters: the government’s assertion

that under no circumstances would it respond to such events with a revised budget would not

have been taken at face value.

35

At the same time, an escape clause not limited to events beyond

control of the government, lacking explicit thresholds for activation, and with no provision for

independent verification would have been destabilizing; it would have given the government free

rein to disregard its targets. As Valencia, Ulloa-Suárez and Guerra (2024) describe, a well-

designed escape clause must be accompanied by clear triggers and conditions, clear assignment

of responsibility for activation and deactivation, and a clear communication strategy.

32

The IMF and World Bank made adoption of the Fiscal Responsibility Framework conditions of their 2010 lending

programs (IMF 2010) but were unhappy with the incomplete nature of the rules adopted that year; no immediate

changes were made, since the IMF agreement went off track almost immediately, and disbursements were halted.

The IMF then required strengthening of the Framework as a condition for its 2013 arrangement, and the

amendments described later in this paragraph followed in 2014.

33

The rationale for the separate public-sector wage target was that wage compensation was a principal driver of the

fiscal balance. Subsequent experience showed that even when the wage target was missed it still could be possible

to meet the debt and deficit targets; correspondingly, the separate wage target was eliminated in 2023.

34

The 2026 deadline was pushed back to 2028 due to the pandemic, in an example of the operation of the escape-

clause mechanism described below.

35

IMF (2013, p.13) noted that “Given the frequency of hurricanes, any credible rule should contain an escape clause

to be activated in the event of an extraordinary storm.”

13

Jamaica’s escape clause satisfies these prerequisites. It can be activated only in response

to a natural disaster, a public health or other emergency, or a severe economic downturn (of 2

percent of GDP in a quarter). It can be invoked only after verification by the Auditor General,

whose independence from other government agencies is guaranteed by the constitution, that the

fiscal impact exceeds a minimum threshold of 1.5 percent of GDP. The Auditor General must

submit its assessment to Parliament, along with supportive documentation from the Ministry of

Finance, and suspension of the fiscal rule must be approved by both Houses. Valencia et al.

(2024) rate escape clause clarity on six dimensions and give Jamaica’s escape clause a rating

well above the Latin American and Caribbean average.

The government was thus able to invoke this escape clause in response to COVID-19,

reducing the VAT rate and increasing spending on health and social protection. It deactivated

the clause only after one year; the short duration of the suspension speaks to the credibility of the

arrangement, given the severity of the COVID crisis.

36

In contrast, Hurricane Matthew caused

widespread damage in 2016 but was deemed not to meet the fiscal threshold and hence did not

precipitate suspension of the rule.

The Framework corrects specific institutional weaknesses that had led to deficit

overshooting in the past. The Minister of Finance is obliged to submit to Parliament a Fiscal

Responsibility Statement describing the overall strategy. The Minister is also required to submit

a Fiscal Management Strategy that reports and explains deviations between fiscal targets and

outcomes over the preceding year and projects the government’s finances over the coming three

fiscal years, together with a Macroeconomic Framework outlining the assumptions behind these

revenue and spending estimates. The independent Auditor General is then tasked with

examining the Ministry’s reports and providing an assessment to Parliament within six weeks of

the Ministry’s submission.

37

This Framework addressed the problem of excessive public-sector wage growth by

requiring the Ministry of Finance to describe a specific trajectory for bringing public-sector

wages down to 9 percent of GDP by the end of fiscal year 2016. Together with concurrent

amendments to the Public Bodies Management and Accountability Act, it required public bodies

to prepare and submit information on their financial performance in the current and preceding

years, together with explanations for deviations from budget, to be used as input for the Fiscal

Responsibility Statement. The Framework enforces a time limit for these submissions and

subjects them to independent assessment by the Auditor General.

In sum, the Fiscal Responsibility Framework provided concrete numerical targets for

debts and deficits, along with associated deadlines and a well-defined escape clause; required the

Minister of Finance to provide multi-year plans for how the targets will be achieved; mandated

the transparency of assumptions and forecasts, together with independent assessments by the

Auditor General; and held the central government and public bodies accountable for revenue

shortfalls and expenditure overruns.

36

Invoking the escape clause entailed delaying the deadline for bringing the debt/GDP ratio down to 60 percent by

24 months.

37

An important observation which bears on the question, asked below, of whether lessons from Jamaica generalize

is that the Auditor General is a strong institution and office, given this constitutional guarantee and the weight of

history.

14

4B. Institutionalized Partnership and Monitoring

The failure of fiscal adjustment efforts in 2010-12 indicates that the rules adopted in

2010, by themselves, were not enough. There remained a significant danger of the process being

derailed until the Economic Programme Oversight Committee (EPOC) was created in 2013 and

until EPOC was supported by the signing of a meaningful national partnership agreement (The

Partnership for Jamaica Agreement) that same year. The Partnership for Jamaica Agreement

affirmed that the government, political opposition, and social partners had reached a consensus

on policy priorities; it committed the parties to monitoring the conformity of public policies with

those priorities. EPOC meanwhile enabled financial stakeholders to track fiscal policies and

hold the government accountable for its budgetary actions. We think of the National Partnership

Council (NPC), which produced the Partnership for Jamaica Agreement, as a consultative and

consensus-building institution designed to create confidence that the burden of fiscal adjustment

was equitably shared – as an example of the approach to consensus building known in the

literature as “democratic corporatism.” We think of EPOC primarily as a monitoring and

information-dissemination technology focused on the budget.

38

The NPC in fact drafted a series of “Partnership Agreements,” some of which were more

substantive than others. The first such agreement in 2011 was a mere “code of conduct”

including no specific commitments.

39

The political opposition consequently boycotted its

signing, indicative of a lingering lack of trust. The 2013 Partnership for Jamaica Agreement,

which coincided with the inauguration of sustained debt reduction, was very much more detailed.

It was the outcome of an extended round of consultations on specific issues, including debt. The

document started by acknowledging the sense of crisis created by “inter alia, an unsustainable

debt-to-GDP ratio.” It spoke of the need for social dialogue and participatory decision making to

engender “trust and confidence among the Partners…” It provided commitments by both the

government and the opposition to the principles of transparency, accountability, and

consultation, and to the pursuit of “long-term national goals rather than short-term political

imperatives”; by business to limit profit margins; from trade unions to address problems of low

productivity; and by representatives of civil society to help “stabilise and transform the

economy.” It then presented four specific policies requiring monitoring and accountability, of

which “Fiscal Consolidation (with Social Protection and Inclusion)” had priority of place.

40

The NPC agreed to monitor the compliance of parties to the terms of this agreement in a

manner complementary to the other newly created oversight body, the Economic Programme

Oversight Committee, that focused more closely on fiscal functions. EPOC was established

specifically to reassure domestic holders of sovereign bonds that the government would keep to

its fiscal commitments, including the rules set out under the Fiscal Responsibility Framework.

The government had completed a first domestic debt exchange in 2010, as noted in Section 3, as

a precondition for the 2010 IMF Stand-By Arrangement. But that arrangement was off-track

already in early 2011, due to an overrun of the 9 percent public-sector wage/GDP target. The

prime minister resigned in October, and his party was immediately voted out of office, raising

questions about its successor’s intentions. The new government then tabled a second domestic

38

In practice there was overlap between the objectives and deliberations of the two entities, as we make clear below.

39

It had simply listed a set of “key guiding principles” such as sensitivity, courage, patience and understanding.

40

The other three were rule of law adherence; ease of doing business and employment creation; and energy

diversification and conservation.

15

debt exchange, also described in Section 3, with an eye toward securing a new IMF agreement.

41

This time, however, debt holders refused to participate absent assurances that any additional

maturity extensions and coupon reductions would be the last. Hence the creation of EPOC to

monitor implementation of the government’s economic reform measures and specifically its

compliance with IMF targets and conditions.

EPOC has 11 members representing the public sector, trade unions, business, and

finance, with relatively heavy representation of this last category. This difference in composition

compared to the NPC, specifically greater representation of financial interests, reflects EPOC’s

focus on fiscal questions.

42

EPOC issues reports, typically quarterly, on fiscal-policy conduct

and outcomes, comparing realized tax revenues and expenditures with those budgeted, and

analyzing their determinants. It has continued to do so since the country’s ongoing arrangement

with the IMF concluded in 2019. This is a key observation: monitoring was shared with the IMF

virtually from the start, and it has continued long since the IMF exited the scene.

EPOC’s assessments are posted on its website, together with communiques and video

recordings by its chair. In addition, EPOC started a program called “On the Corner” that

involved going from town to town with reports in hand, explaining what the debt reduction

program was designed to achieve. These consensus-building efforts were followed by a visible

improvement in public opinion: survey data from the Latin American Public Opinion Project

show little change between 2006 and 2014 in the share of the public thinking that the economic

situation was improving and then a steady increase after 2014.

43

Recently the government and Parliament agreed to provide a proper legal basis and full

independence for its proceedings by creating a Fiscal Commission to “provide an informed

second opinion on fiscal developments, and…play a constructive role in informing the public

and, in so doing, incentivizing adherence to Jamaica’s fiscal rules.”

44

EPOC will stop meeting

once the Fiscal Commission is fully staffed and operational in fiscal year 2024.

4C. Ownership

Jamaica was under IMF programs in 2010-11 and earlier, but those programs went off

track. They did not result in sustained debt reduction. This earlier experience and experience of

myriad other countries are reminders that IMF involvement is no guarantee of success.

The difference in Jamaica starting in 2013 involves that oft-mentioned but rarely

explained, or even defined, concept of ownership. By ownership we mean that country

authorities and, importantly, stakeholders to whom those authorities are accountable develop and

41

This involved tapping the IMF’s Extended Fund Facility (EFF), which provides assistance to countries with

medium- as opposed to short-term balance of payments problems because of structural issues or slow growth.

Jamaica’s 2013 EFF arrangement was for four years.

42

At the same time, EPOC has sufficiently broad non-financial-sector representation to effectively supplement the

dialogue and consensus-building efforts of the NPC. Members engage in dialogue and consensus building that

allows the principal stakeholders to monitor and express their views regarding the conformity of fiscal policies with

shared public priorities of fiscal accountability and equitable burden sharing.

43

The precise question asked is “Do you think the country’s current economic situation is better than, the same as or

worse than it was 12 months ago?” See https://www.vanderbilt.edu/lapop/

44

Quoted from Finance Minister Clarke’s budget presentation to the House of Representatives (7 March 2023):

Clarke (2023).

16

maintain a broad and credible commitment to the agreed program of policies.

45

In Jamaica, the

commitment was broad because it was based on an encompassing partnership agreement that the

burden of adjustment would be widely and fairly shared. It was credible because policies and

outcomes could be benchmarked against concrete rules and thresholds, and because there existed

institutionalized monitoring mechanisms to verify the compliance of stakeholders with their

commitments.

Well-defined rules and robust partnerships made for ownership of the country’s fiscal

adjustment and IMF programs. Jamaican officials successfully completed the first 10 quarterly

reviews under the 2013-17 Extended Fund Facility Arrangement. Even when there was a change

of government from the PNP to the JLP in March 2016, debt reduction continued. The new JLP

administration successfully completed the 11

th

, 12

th

, and 13

th

quarterly reviews with the IMF and

then surprised all concerned by announcing the early ending of the Extended Fund Facility and

immediately entering a precautionary Stand-By Arrangement.

46

When the IMF and Jamaican

authorities held a High-Level Caribbean Forum in Kingston in November 2017, leaders of both

political parties endorsed institutionalizing EPOC. The following April the Cabinet embraced

the concept of an independent fiscal institution. One month later, the Minister of Finance

delivered a speech, “Enhancing Jamaica’s Fiscal Responsibility Framework,” initiating another

consultative process designed to transfer responsibility for budgetary monitoring from the ad hoc

body EPOC to a permanent, independent Fiscal Commission.

4D. Origins

The question is how Jamaica was able to reduce political polarization and achieve a broad

social consensus in favor of debt reduction. And how and why did it create the institutionalized

partnerships that were central to this process?

Here again our answer has two parts. The first element is Jamaica’s historical journey: its

troubled history as an independent nation and the lessons drawn from that early experience by

political leaders and the public. Over time, that experience and those lessons translated into a

visible decline in political polarization. The second element is the construction of institutions for

monitoring, consensus building, and cohesion, first in the electoral realm, where the need was

most pressing, but then in the areas of economics, finance, and finally fiscal policy, where policy

makers could build on earlier precedents and achievements.

Jamaica was not always a cohesive society. Shortly after independence, Yale sociologist

Wendell Bell (1962) observed of the country: “The white upper classes, the brown middle

classes, and the black lower classes are grossly unequal with economic and social advantages

accruing most to the upper and least to the lower classes.” This sense of inequality fueled the

PNP’s 1972 electoral victory and its subsequent populist rhetoric and policies. One year before

the 1976 election in which PNP Prime Minister Michael Manley won a second term, he declared:

“Jamaica has no room for millionaires.” For those who wanted to be millionaires, he suggested,

“We have five flights a day to Miami.” (Levi 1990, p. 157). In response to the PNP’s rhetoric

and policies, the opposition JLP moved further to the right. Accusations of electoral

45

Boughton (2003) is one of the rare sources providing an actual definition along these lines.

46

Precautionary arrangements are for cases when countries do not intend to draw on the IMF facility but retain the

option of doing so.

17

intimidation, malfeasance and fraud were widespread (Electoral Commission of Jamaica 2014,

pp.18-19). Political violence soared: election season saw rampant shootings in Kingston’s

“garrisons” of those thought to favor the political opposition. Estimates are of more than a

hundred politically motivated murders in 1976 and more than 800 in 1980.

This ghastly situation created a groundswell for reducing political polarization and

violence. Prominent public figures took the lead: during the One Love Peace Concert, before an

audience of more than 30,000, the country’s leading artist, Bob Marley, joined hands on stage

with the prime minister and the leader of the opposition. Following their defeat in the 1980

election, Manley and the PNP moderated their rhetoric and policies. On retaking office in 1989,

the PNP embraced the JLP’s previously implemented economic reforms, as noted in Section 2.

Manley himself articulated the Party’s new more collaborative, centrist approach to economic

policy:

“[The PNP], like many other people in the broad social democratic movement,

placed greater reliance at that time on the capacity of the state to be a direct

factor in production. Experience showed us that the state is not necessarily a

reliable intervener in production. You stretch your managerial capacity and

create tensions with the private sector that can be counterproductive. So the

second great lesson that we learned is not really to depend on the government

as a factor in production but rather to use government as an enabling factor for

the private sector” (Massaquoi 1990, p. 112).

Given Manley’s personal popularity, his party’s endorsement of this newfound economic

policy consensus played an important role in creating a less polarized political environment

conducive to constructive engagement. This is evident in Figure 2, where we see discrete steps

down in political polarization after 1980 and again after 1989.

The second element was institution building. To address problems of electoral

intimidation and fraud, leaders of both parties agreed that oversight of elections should be

removed from the direct ministerial control of the government. Following the recommendations

of a bipartisan commission, Parliament voted in 1979 to create an independent, nonpartisan

institution with representation of both political parties and civil society to monitor and validate

electoral results. This Electoral Advisory Committee (EAC) consisted of eight members: the

Director of Elections, three members of civil society, and four nominated members (two each

from the JLP and PNP).

47

The EAC was “not answerable to any minister of government”

(Electoral Commission of Jamaica 2014, p. 21). It was a venue for dialogue between the parties

and other stakeholders, and had independent authority to invalidate any election result tainted by

violence or malfeasance.

48

The EAC was a first step on Jamaica’s journey toward social partnership. It was the

precedent for the creation, over the next three decades, of a series of other independent, multi-

47

Civil society representatives were selected by the Governor-General. The Governor-General, a legacy of the

British Commonwealth, represents the monarch on ceremonial occasions and has various powers, sporadically

exercised, under the constitution. The EAC was unlike other standing commissions, such as the Public Service

Commission and Police Commission, in that the Director-General took advice directly from both the prime minister

and the leader of the opposition and not just from the prime minister.

48

For a detailed discussion of the workings of the EAC and the process by which it was created, see Electoral

Commission of Jamaica (2014), pp. 20-40.

18

stakeholder consultative bodies that addressed not electoral intimidation and fraud but other

issues, notably including economic growth and debt reduction. These subsequent steps are shown

in Table 2.

The National Planning Council in 1989 was the next significant institutional innovation:

its 22 members brought together government officials with business, trade union and other

private sector members (representing academic, professional and consumer interests) in monthly

meetings intended to “contribute to the formulation of economic policies and programmes, to

assess economic performance and to identify measures designed to achieve broad-based

development and growth in productivity, employment and the national product” (Government of

Jamaica 1989).

The National Planning Council was followed in 1997 by ACORN, a venue for social

dialogue “in which leaders of the Country's labour unions, private sector and academia have met

together continuously over the last twenty-one years, focusing on building social capital and trust

among actors in key sectors of the Jamaican society in pursuit of national growth and

competitiveness” (Wint 2018). The launch of ACORN again coincided with a visible drop in

political violence and a drop in political polarization centered on 1999. ACORN is widely

viewed as a progenitor of the partnership committees and councils culminating in creation of the

National Partnership Council in 2009, as described in Section 4B. Creation of the National

Partnership Council was followed by one of Jamaica’s largest post-independence declines in

political polarization and political violence (again see Figure 2). This became the vehicle for the

landmark Partnership for Jamaica Agreement in 2013 and its sequel, the Partnership for a

Prosperous Jamaica, when the government changed hands in 2016.

Building on this foundation, Jamaican leaders used this same approach of building

encompassing institutions with independent powers starting in 2010 when the issue became

fiscal adjustment and debt sustainability. Table 3 shows the sequence of institutional steps,

starting with introduction of the Fiscal Responsibility Framework in 2010 and continuing with

creation of the Economic Programme Oversight Committee in 2013. A sense of crisis informed

the decision to create EPOC in 2013, just as a sense of crisis had informed the decision to create

the Electoral Advisory Commission in 1979. In 1979, political violence had threatened

Jamaica’s survival as a political democracy. In 2013, normalizing the finances was “essentially a

matter of survival of the Jamaican nation as a viable nation state,” as Peter Philips, the Minister

of Finance, put it

.

49

The generous representation of financial interests on EPOC was important for

disciplining and creating confidence in fiscal and financial policies, as argued above. Jamaica’s

specific approach to debt restructuring had a lot to do with the development of this particular

institutional configuration. Governments are typically more inclined to restructure external than

domestic debts.

50

Historically, domestic debt has been held by residents, who are also citizens

and voters. Incumbent governments prefer to avoid subjecting them to financial pain, knowing

that those voters can retaliate by inflicting electoral pain. In addition, where domestic debt is

held by local financial institutions, there can be fear that restructuring it could destabilize the

financial system. In Jamaica, unusually, a combination of practicalities and legal restrictions

made it more expedient to restructure domestic debt. This meant that local financial institutions,

49

Quoted in Wigglesworth (2020).

50

Though not always: see Reinhart and Rogoff (2011).

19

which held this debt, became highly attentive to fiscal developments. Because the painful 2010

restructuring, was unsuccessful, in that it did not help to put the country on the path to sustained

debt reduction, local financial institutions refused to participate in the deeper 2013 restructuring

without further reassurance. They viewed the creation of EPOC, their ample representation, and

the efficient operation of its monitoring and consultation functions as a non-negotiable

precondition for their participation in this second round.

While EPOC had relatively heavy representation of financial interests and focused on

monitoring fiscal policies and outcomes, including those associated with the IMF’s Extended

Fund Facility (EFF), it did not do so to the exclusion of other issues, such as collective

bargaining. The unions had agreed to a two-year public-sector wage freeze as part of the failed

2010 Stand-By Agreement. Just as investors were now willing to accept further maturity

extensions and coupon reductions only as part of a successful program, unions were prepared to

extend the wage freeze only if they were confident that the broader stabilization program had a

reasonable chance of success. Their representation on EPOC was important for creating this

confidence. In the words of Philips, the monitoring and deliberations of EPOC “did much to

build public support across class lines, and I dare say, across political lines for the necessity of

the fiscal consolidation and pro-growth efforts at public sector reform and legislative reforms…”

(Philips 2017, p.2). As further explained by Clarke (2018, p.10),

“…the consensus building mechanisms of non-governmental bodies had, and

continue to have, an indispensable role to play. It was against this background

that the previous administration approached members of the financial

community with a second debt exchange and the unions with a multi-year wage

freeze as prior actions for entry into the Extended Fund Facility. Both groups

correctly insisted on the right to monitor Jamaica’s economic program in return

for such sacrifices, in order to ensure that Jamaica maintained its commitments

to the reforms embedded in the agreement with the IMF. And so EPOC was

born...”

This passage makes clear that while the focus of EPOC monitoring was fiscal policy and

Jamaica’s commitments to the IMF, the committee entailed a broader social partnership in the

manner of the other multi-partner consultative bodies that preceded it. And while EPOC’s

establishment coincided with the country’s entry into the EFF, the impetus for its creation came

exclusively from Jamaica. As IMF Managing Director Christine Lagarde noted in 2014,

monitoring of an IMF reform program by an “outside group…is something that I have never

heard of [and] that none of my staff had heard of…”

51

5. Do the Lessons Generalize?

Does the Jamaican case generalize? Can other economies similarly shed heavy debt

burdens by strengthening fiscal rules and backing them with consensus-building institutions?

The IMF evidently thinks so: its current Managing Director has pointed to Jamaica as a model to

be followed (Georgieva 2019).

52

At the same time, the fact that Jamaica’s case is widely seen as

51

Ibid.

52

Similarly, her predecessor, Lagarde, in the interview just quoted, went on to suggest that “This surely is a role