FINANCING

THE REAL ECONOMY

P A K I S T A N

DEVELOPMENT UPDATE

April 2022

PAKISTAN DEVELOPMENT UPDATE

Financing the Real Economy

April 2022

Preface

The World Bank Pakistan Development Update (PDU) provides an update on the Pakistani economy, its economic

outlook, together with the development challenges it faces and the structural reforms that should be considered.

This edition of the Pakistan Development Update (PDU) was prepared by the Macroeconomics, Trade, and

Investment Global Practice under the guidance of Najy Benhassine (Country Director, SACPK), Zoubida Allaoua

(Regional Director, ESADR), Shabih Ali Mohib (Practice Manager and Lead Country Economist, ESAMU) and

Gabi George Afram (Practice Manager, ESAF1). The core PDU team was led by Zehra Aslam (Task Team Leader

and Economist, ESAMU) and Namoos Zaheer (Co-Task Team Leader and Senior Financial Sector Specialist,

ESAF1), and includes Miquel Dijkman (Lead Financial Sector Specialist, ESAF1), Derek H. C. Chen (Senior

Economist, ESAMU), Gonzalo J. Varela, (Senior Economist, ESAMU), Adnan Ashraf Ghumman (Senior

Economist, ESAMU), Sayed Murtaza Muzaffari (Economist, ESAMU), Aroub Farooq (Research Analyst, ESAMU),

Franz Ulrich Ruch (Economist, EPGDR), Rafay Khan (Economist, ESAF1), Fahad Hasan (Financial Sector

Specialist, ESAF1), Noor Yasin (Extended Term Consultant, ESAF1) Arsianti (Consultant, ESAMU), and Ali

Shahid (Team Assistant, SACPK).

Sections 1 and 2 of the report were contributed by Zehra Aslam, Aroub Farooq, Sayed Murtaza Muzaffari, Franz

Ulrich Ruch, Fahad Hasan. Namoos Zaheer, Rafay Khan, Fahad Hasan, Noor Yasin contributed Section 3. The

report benefitted from comments provided by Mustapha K. Nabli. The report was edited by Janani Kandhadai.

The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this report do not necessarily reflect the views of the

Executive Directors of the World Bank or the governments they represent. The World Bank does not guarantee

the accuracy of the data included in this work. The data cut-off date for this report was March 31, 2022. The

boundaries, colors, denominations, and other information shown on any map in this work do not imply any

judgment on the part of the World Bank concerning the legal status of any territory or the endorsement or

acceptance of such boundaries.

The photograph for the front cover is by Abdullah Hussain/https://www.pexels.com/@abdullahbaloch.

To receive the PDU and related publications by email, please email ashahid2@worldbanko.org. For questions and

Table of Contents

PREFACE ............................................................................................................................... IV

LIST OF FIGURES, TABLES AND BOXES ........................................................................ VI

LISTS OF ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS ............................................................ VII

1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY – FINANCING THE REAL ECONOMY .............................. 1

2. RECENT ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENTS ...................................................................... 3

a. Context .......................................................................................................................................... 3

b. Real Sector .................................................................................................................................... 3

Growth .......................................................................................................................................... 3

Inflation ........................................................................................................................................ 4

Poverty and Equity ....................................................................................................................... 5

c. Monetary and financial sector ....................................................................................................... 6

Monetary ....................................................................................................................................... 6

Financial Sector ............................................................................................................................ 7

d. External sector .............................................................................................................................. 7

e. Fiscal and Debt Sustainability ...................................................................................................... 9

f. Medium-Term Outlook ............................................................................................................... 12

g. Risks and Priorities ..................................................................................................................... 13

3. SPECIAL FOCUS – FINANCING THE REAL ECONOMY ................................... 15

a. Importance of Finance and the Financial Sector ........................................................................ 15

b. Structure of Pakistan’s Financial Sector ..................................................................................... 16

c. The Untapped Potential of the Financial Sector ......................................................................... 18

d. Structural Impediments to the Financial Sector’s Potential ....................................................... 22

e. Enhancing the Flow of Financing to the Real Economy............................................................ 27

REFERENCES ..................................................................................................................... 30

STATISTICAL ANNEX ....................................................................................................... 33

List of Figures, Tables and Boxes

FIGURES

Figure 2.1: Contribution to headline inflation in urban areas ........................................................... 5

Figure 2.2: Contribution to headline inflation in rural areas ............................................................ 5

Figure 2.3: H1 Current Account Balances (Jul–Dec) ........................................................................ 8

Figure 2.4: H1 Financial Account Inflows (Jul–Dec)........................................................................ 8

Figure 2.5: Import of goods and services (Jul–Dec) ......................................................................... 8

Figure 2.6: Export of goods and services (Jul–Dec) ......................................................................... 8

Figure 2.7: Consolidated Fiscal and Primary Balance (excluding grants) in H1 ........................... 10

Figure 2.8: Budgetary Financing: Net External and Domestic Inflows in H1 ............................... 10

Figure 2.9: Consumer price inflation .............................................................................................. 14

Figure 2.10: Sovereign spread.......................................................................................................... 14

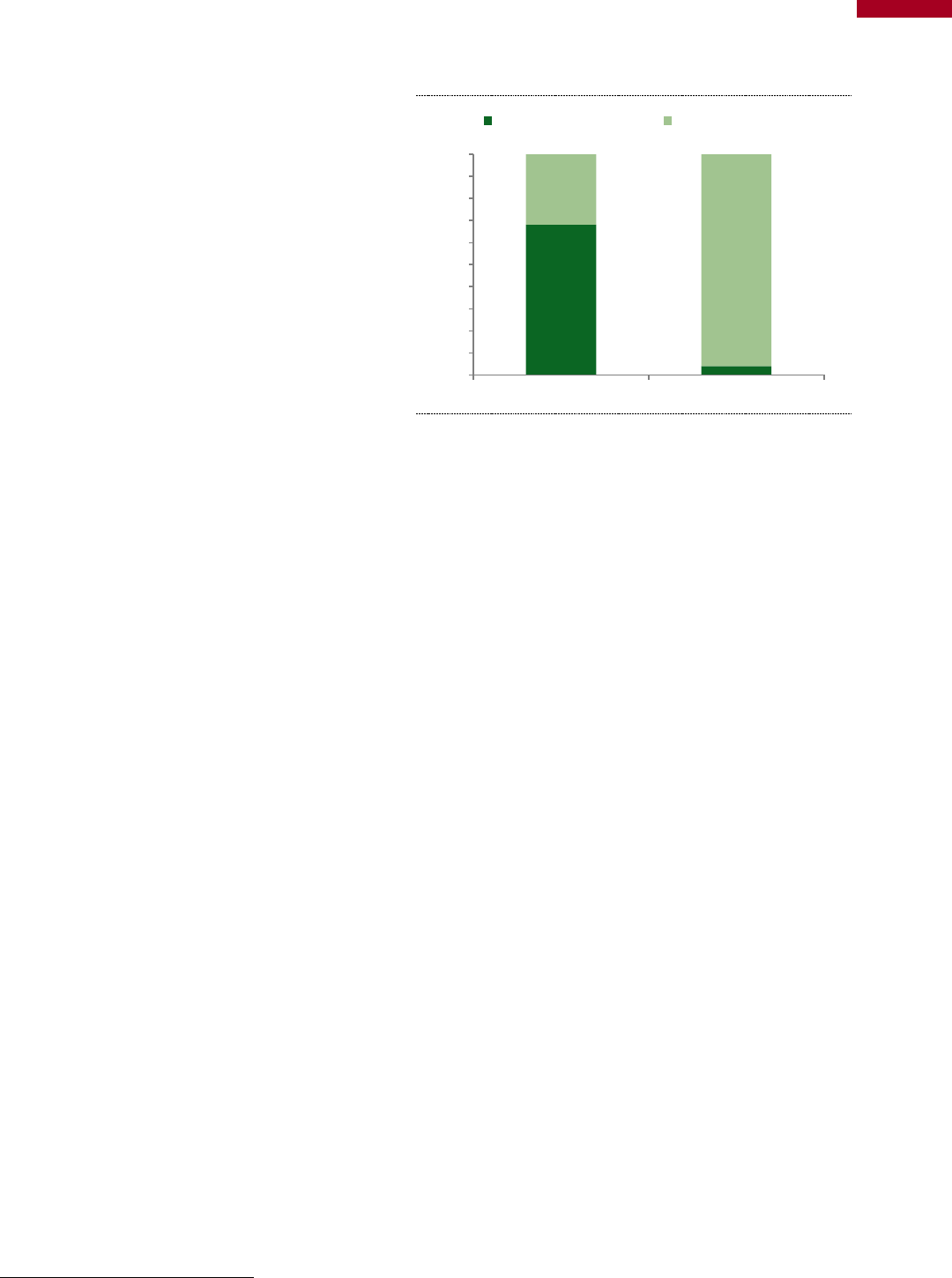

Figure 3.1: Private investment, selected years................................................................................. 15

Figure 3.2: Distribution of financial sector assets, December 2020 ................................................ 16

Figure 3.3: Distribution of non-bank financial institutions assets, November 2020 ...................... 16

Figure 3.4: Deposit Money Banks’ Assets ...................................................................................... 18

Figure 3.5: Credit to Private Sector ................................................................................................. 18

Figure 3.6: Advances to Deposits ratios .......................................................................................... 18

Figure 3.7: Advances by sector, FY21 .............................................................................................. 19

Figure 3.8: SME finance .................................................................................................................. 20

Figure 3.9: Sectoral financing as a share of private sector financing .............................................. 20

Figure 3.10: Type of financing ........................................................................................................ 20

Figure 3.11: Evolution of the deposit structure ............................................................................... 20

Figure 3.12: Market capitalization ................................................................................................... 21

Figure 3.13: MFPs as a share of borrowers and financing portfolio ............................................... 22

Figure 3.14: Government Borrowing from Banks, FY11–21 ............................................................ 23

Figure 3.15: Credit to Government and state-owned enterprises, 2019 ........................................... 23

Figure 3.16: Gross Savings .............................................................................................................. 24

Figure 3.17: Account ownership at a financial institution or with a mobile-money-service provider

.................................................................................................................................................... 24

TABLES

Table 1: Projections of Key Economic Indicators............................................................................. 2

Table 2.1: Pakistan Macroeconomic Outlook (FY22-24) ................................................................ 13

Annex Table 1: Key Macroeconomic indicators (annual) ............................................................... 33

A

nnex Table 2: Balance of payments summary

1

............................................................................. 33

Annex Table 3: Summary of Pakistan’s Fiscal Operations ............................................................. 34

BOXES

Box 2.1: Strengthening the Autonomy of the SBP – State Bank of Pakistan Amendment Act 2021 . 6

Box 2.2: Finance (Supplementary) Act 2022 .................................................................................... 11

Box 2.3: Moderating global growth in a higher inflation, tighter financial conditions, and uncertain

environment ............................................................................................................................... 14

Box 3.1: SBP’s Banking on Equality Policy: Reducing the Gender Gap in Financial Inclusion ... 25

Lists of Abbreviations and Acronyms

ADR Average Advances to Deposit ratio

BISP Benazir Income Support

Programme

BPM6 Balance of Payments Manual 6

CAD Current Account Deficit

CAR Capital Adequacy Ratio

CDNS Central Directorate for National

Savings

CPI Consumer Price Index

CRR Cash Reserve Requirement

DFI Development Finance Institution

DSSI Debt Service Suspension Initiative

e-CIB Electronic Credit Information

Bureau

EFF Extended Fund Facility

EFS Export Financing Scheme

EMBI Emerging Market Bond Index

EMDE Emerging Market and

Development economy

EU European Union

FBR Federal Board of Revenue

FDI Foreign Direct Investment

FIFRDLA Fiscal Responsibility and Debt

Limitation Act

FY Fiscal Year

GDP Gross Domestic Product

GCC Gulf Cooperation Council

GFP Gross Loan Portfolio

GST goods and services tax

IFC International Finance Corporation

IFS International Financial Securities

IMF-EFF International Monetary Fund-

Extended Fund Facility

IPP Independent Power Producers

JFE Journal of Financial Economics

LSM Large Scale Manufacturing

LTFF Long-Term Financing Facility

MFB Microfinance banks

MFP Micro Finance Provider

MOC Ministry of Commerce

MOF Ministry of Finance

MPC Monetary Policy Committee

MSE Medium and small enterprises

MSME Micro, Small and Medium

Enterprises

NBFI Non-Bank Finance Institution

NCOC National Command and Operation

Center

NFLP National Financial Literacy

Program

NPL(s) Non-Performing Loan(s)

OECD Organization for Economic Co-

operation and Development

PBS Pakistan Bureau of Statistics

PCRCL Pakistan Credit Restructuring

Company

PD Primary Dealers

PDU Pakistan Development Update

PDL Petroleum development levy

PE Public Equity

PFI Public Financial Institute

PKR Pakistani Rupee

PPP Purchasing power parity

PSCB Public Sector Commercial Bank

PSX Pakistan Stock Exchange

REITS Real Estate Investment Trusts

REER Real Effective Exchange Rate

SBP State Bank of Pakistan

SCRR Special Cash Reserve Requirement

SECP Securities Exchange Commission

SME Small and Medium Enterprise

SOE State Owned Enterprises

STR Secured Transactions Registry

TERF Temporary Economic Refinance

Facility

UNCTAD United Nations Conference on

Trade and Development

VC Venture Capital

WDI World Development Index

WBG World Bank Group

y-o-y Year-on-year

Financing the Real Economy

Pakistan Development Update

April 2022

The World Bank

1

1. Executive Summary – Financing the Real Economy

Economic activity

has

remained strong

since July 202

1

Economic momentum continued over July–December 2021 (H1 FY22) as indicators

mostly signaled positive trends.

With sustained

improvement in community mobility and

still

-robust official remittance inflows, private consumption is estimated to

have

increased

. Similarly, public and private investment is expected to have grown

with the

strong growth of machinery imports and government development expenditure.

Government consumption

is also estimated to have grown

due to vaccine procurement.

On the production side, agricultural output, mainly rice and sugarcane increased,

reflecting better weather conditions.

Large-scale manufacturing (LSM)

growth rose to 7.5

percent y

-o-y in H1 FY22, higher than the 1.5 percent for H1 FY21. However, with higher

inflation

, increasing borrowing costs and political uncertainty,

business and consumer

confidence have been trending lower after reaching a pandemic high in June 2021.

Average headline

inflation increased

largely due to higher

energy prices

Headline inflation rose to an average of 9.8 percent y-o-y in H1 FY22 from 8.6 percent

in H1 FY21, driven by surging global commodity and energy prices and a weaker

exchange rate. Similarly, core inflation has been increasing since September 2021.

Accordingly, the State Bank of Pakistan (SBP) has been unwinding its expansionary

monetary stance since September 2021, rai

sing the policy rate by a cumulative 525

basis

points (bps) and banks’ cash reserve requirement by 100 bps.

The current account

deficit

widened

sharply

, heightening

external

sustainability risks

and

reinforcing

downward

pressures

on the Rupee

The current account deficit (CAD) in H1 FY22 widened to US$9.0 billion, from a surplus

of US$1.2 billion in H1 FY21, as imports values surged by 54.4 percent, doubling the 27.3

percent growth in exports values.

The record-high trade deficit was partially financed by

remittances

that registered double-digit growth in H1 FY22

. The financial account

recorded net inflows of US$10.1 billion, supported by the new IMF SDR allocation,

short

-term government deposits from Saudi Arabia, and a

Eurobond issuance in July

2021.

In January-February 2022, the Government obtained US$2.1 billion from an

International Sukuk

issuance and the IMF Extended Fund Facility (EFF).

Despite these

inflows, foreign exchange reserves

fell to US$12.9 billion at end-March 2022,

the lowest

since June 2020, and

equivalent to 1.9 months of imports of goods and services.

1

Meanwhile, the Rupee depreciated

by 14.3 percent against the U.S. dollar

from July 2021

to end-March 2022, reaching multiple record lows over the period.

The fiscal deficit

widened

due to

higher spending

Despite high tax revenue growth on the back of surging imports, the fiscal deficit widened

by 20.6 percent in H1 FY22 due to higher spending on vaccine procurement, settlement

of power sector arrears, and development projects. Public and publicly guaranteed debt

stood at PKR45.3 trillion at end

-December 2021,

an increase of PKR3.1 trillion since

end

-June 2021. As part of reforms to increase domestic revenues, the Government

also

approved a Supplementary Finance Bill in January 2022, withdr

awing two-thirds of

tax

exemptions on the General Sales Tax (GST).

GDP growth is

projected to

moderate

in FY22–

23, before

strengthening over

the medium-term

On the back of high base effects, recent monetary tightening and stronger inflation, real

GDP growth is expected to

moderate

to 4.3 and 4.0 percent in FY22 and FY23,

respectively

before recovering to 4.2 percent in FY24 (Table 1). T

his recovery is

predicated on

continued macroeconomic stability and

a narrowing of the fiscal and

external deficits in the medium

-term. Inflation is estimated to rise to an average of

10.7

1

However, part of the decline in reserves is expected to be reversed in the coming weeks as official creditors rollover their loans.

With the economic

recovery in FY21,

poverty is estimated

to have declined

With the economic recovery and improved labor market conditions, poverty measured at

the lower middle

-

income class poverty line of $3.20 PPP 2011 per day is estimated to

have declined

from 37.0 percent in FY20 to 34.0 percent in FY21. Rising food and energy

inflation is expected to diminish the real purchasing power of households,

disproportionally affecting poor and vulnerable households that spend a larger share of

their budget on th

ese items.

In response, the Government introduced a targeted food

subsidies program and announced a universal fuel price cut in February 2022.

Financing the Real Economy

Pakistan Development Update

April 2022

The World Bank

2

percent in FY22, reflecting higher oil and commodity prices, but is then expected

to decrease over the forecast horizon.

Table 1: Projections of Key Economic Indicators

FY19

FY20

FY21

FY22e

FY23f

FY24f

Real GDP growth, at constant factor prices

3.1

-1.0

5.6

4.3

4.0

4.2

Current Account Balance (% of GDP)

-4.2

-1.5

-0.6

-4.4

-3.1

-3.0

Fiscal Balance (% of GDP), excluding grants

-7.9

-7.1

-6.1

-6.3

-6.1

-5.3

Public Debt, including govt. guaranteed debt (% of GDP)

78.0

81.1

76.0

76.0

74.4

72.5

Sources: Pakistan Bureau of Statistics, State Bank of Pakistan, World Bank staff estimates.

Note: This macroeconomic outlook uses the re-based national accounts data at 2015-16 prices. It was prepared by World Bank staff and

differs from that of the Government.

The CAD is

expected to

increase

in FY22 before

narrowing over

FY23

–24

Due to faster import than export growth in H1 FY22, the CAD is expected to increase

to

4.4 percent of GDP in FY22. Moderating demand pressures due to m

onetary

tightening

, lower global commodity prices and the weaker currency are

expected to

dampen

imports in FY23.

With the implementation of reforms to reduce import tariffs

on relevant intermediates for the export sector and increased allocations for export

refinance schemes

, the CAD is expected to further

narrow to 3.0 percent of GDP in

FY24.

The fiscal deficit is

projected to widen in

FY22

The fiscal deficit (excluding grants) is projected to widen slightly to 6.3 percent of GDP

in FY22,

on the back of higher spending on COVID-

19 vaccine procurement, settlement

of energy sector arrears, development spending, and the recently announced food and

energy subsidies

. It is projected to

gradually narrow over the medium term as revenue

mobilization measures take hold, particularly

GST harmonization

and Personal Income

Tax (PIT) reform

.

Public debt as a share of GDP is projected to remain high, but gradually

decline over the medium term.

Ho

wever, in the absence of the implementation of these

critical reforms, fiscal sustainability risks can increase. The macroeconomic outlook is

predicated on the IMF-EFF program remaining on track.

Multiple external

and domestic factors

pose downside risks

to the outlook

Macroeconomic risks are strongly tilted to the downside. They include faster-than-

expected

tightening of global financing conditions, potential

further increases in world

energy prices, and

the possible risk of a return of stringent COVID-19-

related mobility

restrictions.

Moreover, domestic political uncertainty and policy reform

slippages can lead

to protracted macroeconomic imbalances.

Macroeconomic

adjustment measures

are urgently needed

to address external

imbalances

Strong aggregate demand pressures, in part due to accommodative fiscal and monetary

policies, paired with the continued anti

-export bias of the national trade tariff structure

,

have

contributed to a record-high trade deficit, weighing on the Ru

pee and the country’s

limited external buffers.

Given the severity of the

imbalances, macroeconomic adjustment

measures, specifically fiscal consolidation

to complement the ongoing monetary

tightening, are urgently needed.

A deep, innovative,

and inclusive

financial sector is

key for sustained

growth

A well-functioning financial sector that allocates capital to its most productive uses and

shifts risks to those who can best bear them,

is central

to unlocking private investment

and Pakistan’s

growth potential. However, the country’s

financial sector remains

underdeveloped. Credit to the private sector

is low compared to peers and has trended

down

ward since 2005. It is also concentrated in the corporate segment with most of the

financing being extended for working capital and trade,

rather than growth-

enhancing

fixed investments.

Unlocking higher

financial flows to the

real economy

requires addressing

structural

im

pediments

impacting the

demand and supply

of finance

The underperformance of the financial sector is driven by structural impediments in not

only the supply but also in the demand for finance. Extensive government borrowing

from the financial sector has been the single

largest constraint

to the enhanced flow of

financing to the private sector

. Other important factors include low domestic saving

,

growing but still

limited financial inclusion, a

nd market failures in the form of inadequate

financial infrastructure.

Resolving these constraints in the medium- to long-

term requires

concerted efforts by the government, regulators, and other stakeholders. In addition, five

growth areas offer significant potential to unlock greater financing flows toward the real

economy in the short

- to medium-

term. These are: a) digital finance; b) risk capital; c)

microfinance; d) development finance; and e) capital markets.

Financing the Real Economy

Pakistan Development Update

April 2022

The World Bank

3

2. Recent Economic Developments

a. Context

Economic activity

recovered in FY21,

however,

long-

standing structural

issues pose risk

s to

sustainable

economic growth

The Government undertook timely policy measures to mitigate the adverse

socioeconomic impacts of the COVID

-19 pandemic. The State Bank of Pakistan (SBP)

lowered the policy rate

and

announced supportive measures for the financial sector to

help businesses

and the Government expanded the national cash

transfer program on an

emergency basis

.

2

These measures contributed to economi

c growth rebounding to 5.6

percent

in FY21.

3

However, long-

standing structural weaknesses of the economy,

particularly consumption

-

led growth, low private investment rates, and weak exports have

constrained productivity growth

and pose risks to a sustaine

d recovery. Aggregate

demand pressures have built up, in part due to

previously

accommodative fiscal and

monetary policies, contributing to double

-

digit inflation and a sharp rise in the import bill

with record

-high trade deficits in H1 FY22 (Jul–Dec 2021)

. These have diminished the

real purchasing power of households and weighed on the exchange rate and the country’s

limited external buffers.

b. Real Sector

Growth

Economic

momentum

continued

, but

business confidence

has declined

During H1 FY22, y-o-y growth in car production and sales, petroleum sales, and foreign

remittance inflows indicate continued momentum in economic activity and private

consumption.

Similarly, investment is also expected to have increased with a

strong

growth

in machinery imports and government development expenditure. G

overnment

consumption is also expected to have expanded given the 16.0 percent increase in

consolidated current expenditure in H1 FY22. Activity in the external sector was also

vibrant, with import and export values growing by 54.4 percent and 27.3 percent,

respectively. While the flow of bank loans to private businesses grew in this period, it was

led by an increase in working capital or

short-

term financing, particularly as businesses

faced higher input costs

, as opposed to long-

term or fixed investment financing. The

business confidence survey index also declined from

a pandemic high of 64.0

in June

2021 to 53

.4 in December 2021, indicat

ing lower optimism in the business sector

regarding the economic outlook.

4

Favorable weather

conditions are

expected to support

higher overall crop

production

In agriculture, estimates suggest that rice, sugarcane, and maize production will be higher

this year, reflecting better weather conditions.

5

With regards to agriculture inputs

,

agriculture credit disbursement gr

ew 3.9 percent, and farm tractor sales increased

by 21.2

percent

in H1 FY22.

6

Similarly, 97.7 percent of the sowing target for wheat has been met.

7

However, fertilizer and urea off

-take declined y-o-y over Oct-

Dec 2021, which is likely to

negatively impact wheat production.

Cotton production, though likely

higher than last

year, is also expected to be substantially lower than the government estimate of 10.5

million bales.

8

Large-scale

industrial production

growth strengthened

The LSM index, a key indicator for industrial activity, increased by 7.5 percent y-o-y

during H1 FY22 compared to a muted growth of 1.5 percent in H1 FY21

.

Growth was

broad

-based with 16 out of the 22 sectors recording higher production

. Only

pharmaceuticals, rubber products, electronics, fabricated metal, computers, electronics,

2

Through the Ehsaas Emergency Cash program, the Government delivered PKR179.2 billion as emergency cash assistance to 14.8 million

beneficiaries who were at risk of falling into extreme poverty. Ehsaas Dashboard, Government of Pakistan.

https://www.pass.gov.pk/ecs/uct_all.html

.

3

GDP at constant 2015-16 factor prices. The Government updated national accounts data in January 2022, changing the base year from

2005-06 to 2015-16. As part of this rebasing exercise, the coverage of economic activities included in GDP estimates was improved through

new and updated surveys. The re-basing of GDP led to a revision in real GDP growth rates since FY17.

4

A score above 50 indicates optimism. State Bank of Pakistan.

5

Monthly Economic Update & Outlook: October 2021. Ministry of Finance.

6

Ibid.

7

Monthly Economic Update & Outlook: January 2022. Ministry of Finance.

8

Monetary Policy Statement: March 08, 2022. State Bank of Pakistan.

Financing the Real Economy

Pakistan Development Update

April 2022

The World Bank

4

and optical products, and other transport equipment sectors witnessed a contraction.

Domestic cement d

i

spatches, an important indicator of construction sector activity,

increased by 2.0

percent during H1 FY22.

9

Financing for construction activities

also

picked up by 75.3 percent in H1 FY22.

10

Despite intermittent

lockdown

restrictions

, services

sector activity

remained strong

Services sector activity was the most impacted by intermittent disruptions due to COVID

-

19 related mobility restrictions. From early-August to end-September 2021, the

Government

placed restrictions on indoor gatherings and restaurants,

limited market

timings

, and constrained public transport, schools,

and workplaces to operate at only 50

percent occupancy.

11

Similar restrictions were re-imposed for various durations over mid-

January

to mid-March 2022, when infection rates surged with the Omicron wave.

12

However, despite these restrictions, Google mobility trends indicate that activity in retail

and recreation, parks, grocery and pharmacy, and transport

-

related services remained

strong in H1 FY22

with t

he average improving from 0.9 percent in H1 FY21 to 35.1

percent in H1 FY22.

13

Inflation

Average headline

inflation increased in

H1 FY22…

Average headline inflation during H1 FY22 reached 9.8 percent y-o-y compared to 8.6

percent

in H1 FY21 due to surging global commodity and energy

prices and a weaker

Rupee

. Most product categories saw higher y-o-y average inflation in H1 FY22

, and only

three categories recorded

lower inflation: (1) food and non-

alcoholic beverages; (2)

alcoholic beverages and tobacco;

and (3) miscellaneous goods and services. The broad-

based increase in inflationary pressures

also reflects the

buildup in domestic demand

pressures

during this period.

Headline inflation in Pakistan was the highest in South Asia,

where the regional average was 6.0 percent during H1 FY22.

14

…driven in large part

by higher energy

prices

Energy inflation reached 25.1 percent y-o-y in urban areas and 22.6 percent in rural areas

in

H1 FY22 compared to -

3.2 percent in urban areas and 1.4 percent in rural areas during

the same period last year

.

15

The

increase in global oil prices and depreciation of the Rupee

led to more expensive energy imports

. This led to domestic petrol prices rising by

25.0

percent

in H1 FY22, while kerosene and high-speed diesel prices

rose by 27.7 and 20.7

percent, respectively

.

16,17

Meanwhile, the Government also raised electricity tariffs

in

October and November as part of its energy sector reforms (Figure 2.1 and Figure 2.2).

18

Food inflation eased

slightly but

continues to

remain

elevated, with a risk

of further increases

Average food inflation fell from 13.0 percent in urban areas and 15.7 percent in rural areas

during H1 FY21 to 10.6 percent in urban areas and 8.4 percent in rural areas in H1

FY22.

19

Higher domestic production of wheat, maize, rice, and sugarcane in FY21

contributed to lower

food price pressures in H1 FY22.

20

However, as Pakistan is a

net

importer

of edible oil, wheat, sugar, and pulses,

21

the

higher global food prices together

with the weaker exchange rate have added to domestic food inflationary pressures.

9

Monthly Economic Update & Outlook: January 2022. Ministry of Finance.

10

Loans classified by borrowers (by type of finance). State bank of Pakistan.

11

In August, educational institutes were allowed to remain open but for only three days a week and at 50 percent attendance. See: NCOC

expands stricter Covid restrictions to 27 cities citing pressure on healthcare system. Dawn. August 29, 2021.

12

See: 1) NCOC imposes fresh curbs on schools, other sectors in cities with over 10% positivity. The News. January 19, 2022; and 2)

Which Pakistani cities has NCOC lifted COVID-19 restrictions in? Geo News. February 22, 2022; 3) Govt lifts all Covid-related

restrictions as pandemic wanes. Dawn. March 16, 2022

13

Source: Our World in Data. Notes: the Google mobility data represents percentage change in number of visitors to categorized places,

relative to pre-Covid-19 baseline (median value for the five-week period between January 03, 2022, to February 06, 2022). It is based on a

rolling 7-day average.

14

World Bank staff calculations based on data from the CEIC, and the Afghanistan and Bhutan National Statistics Bureau.

15

Energy inflation consists of electricity charges, gas prices, liquified hydrocarbons, solid fuel, and motor fuel.

16

The Pakistani Rupee depreciated by 10.9 percent against the U.S. dollar in H1 FY22, as calculated using end-period exchange rates for

June 2021 and December 2021. Source: International Monetary Fund, International Financial Statistics.

17

Source: World Bank calculations using data from Ministry of Finance, press releases.

18

International Monetary Fund. 2021 Article IV Consultation, Sixth Review under the Extended Arrangement under the Extended Fund

Facility. Staff report. February 2022.

19

Food inflation consists of two product categories: 1) food and non-alcoholic beverages, and 2) alcoholic beverages and tobacco, and the

ready-made food products from the restaurants and hotels category in the CPI.

20

See Footnote 5.

21

Ministry of Finance. Press Release no 616. September 29, 2021.

Financing the Real Economy

Pakistan Development Update

April 2022

The World Bank

5

Core inflation has

been gradually rising

Headline inflation

continued its upward

trend in January

-

March

2022

Urban core inflation (non-food non-energy) rose to an average of 7.0 percent y-o-y in H1

FY22 from 5.5 percent during H1 FY21. Although rural core inflation fell to an average

of 7.2 percent in H1 FY22 from 7.7 percent in H1 FY21, it has been on an upward trend

since October 2021. Price increases were recorded across a range of goods and services

including garments, footwear, construction inputs, transport, education, and health

services. The increase in core inflation partly reflected the depreciation of the Rupee, and

higher domestic demand pressures.

More recently, headline inflation stood at 12.7 percent in March, after reaching 13.0

percent in January 2022 – the highest in two years. Energy inflation eased on a y-o-y basis

while food inflation climbed in Jan-Mar 2022. However, in March, rural core

inflation reached 10.3 percent whereas urban core inflation was 8.9 percent – the

highest in recent years and indicative of broad-based inflationary pressures.

Figure 2.1: Contribution to headline inflation in urban

areas

(Percentage points)

Figure 2.2: Contribution to headline inflation in rural

areas

(Percentage points)

Source: Pakistan Bureau of Statistics and World Bank staff

calculations

Source: Pakistan Bureau of Statistics and World Bank staff

calculations

Poverty and Equity

With the economic

recovery in FY21,

poverty is

estimated

to have declined...

Supported by higher growth and the recovery in the manufacturing and services sectors,

the poverty headcount, measured at the lower

-middle-income class line of US

$3.20 PPP

2011 per day, is

estimated

to have declined from 37.0 percent in FY20 to 34.0 percent in

FY21.

…but rising food

and energy inflation

has diminished the

real purchasing

power of households

Rising inflation has disproportionally affected poor and vulnerable households that spend

a relatively larger share of their budget on food and energy.

More specifically

, the poor

spend around 50 percent of their total consumption on food items, whereas this share is

only 43 percent among the non

-poor. In response, the Government inaugurated

a

targeted commodity subsidy program, Ehsaas Rashan Riayat, in February 2022 to

compensate eligible households for higher prices.

22

22

Under this initiative, 20 million eligible families identified through the Ehsaas Socioeconomic Registry Survey will receive PKR1,000 per

month to purchase flour, pulses, and cooking oil at a 30 percent subsidized rate. Poverty Alleviation and Social Safety Division.

Government of Pakistan. November 3, 2021.

-2

0

2

4

6

8

10

12

14

Food Energy Core inflation Headline inflation

-2

0

2

4

6

8

10

12

14

Food Energy Core inflation Headline inflation

Financing the Real Economy

Pakistan Development Update

April 2022

The World Bank

6

c. Monetary and financial sector

Monetary

In response to

rising domestic

demand

pressures, the

SBP

raised the

policy rate

and

took measures to

normalize

monetary

conditions

To manage increasing domestic demand pressures, the SBP has been unwinding its

accommodative monetary policy stance

– raising the policy rate by a cumulative 275

basis

points

between September and December 2021 to 9.75 percent.

23

However, w

ith headline

inflation

averaging 9.8 percent in H1 FY22, real interest rates has remained negative.

In a move

aimed at normalizing monetary conditions, the SBP also raised

banks’ cash reserve

requirement

by 100 bps

in November 2021.

24

Moreover, to enhance

the predictability of monetary policy

conditions and to reduce uncertainty, the SBP increased the number of Monetary Policy

Committee (MPC) meetings from six to eight a year in November 2021.

25

In January 2022, the

National Assembly approved the State Bank of Pakistan Amendment Act 2021, which

prohibits Government borrowing from the central bank, strengthens the functional and

administrative autonomy of the SBP, and sets price stability as its primary objective (

Box 2.1).

Moreover, w

ith higher-than-expected inflation in March, growing

pressures on the Rupee and

tighter global conditions, the SBP

further

raised the policy rate by another 250 basis points in

April 2022 to 12.25 percent.

26

Box 2.1: Strengthening the Autonomy of the SBP – State Bank of Pakistan Amendment Act 2021

The role of the State Bank of Pakistan (SBP) is defined in the State Bank of Pakistan Act 1956. Further, the Act has been

amended several times over the years to bring its operational and administrative function in line with international best

practices and to allow it to deal with evolving economic conditions more effectively. Most recently in January 2022, the

Parliament approved the SBP Amendment Act 2021, which strengthens the SBP’s functional and administrative autonomy,

defines its objectives clearly, and improves transparency in SBP’s operations. The key changes introduced in this Act are as

follows:

(i) Objectives: The primary objective of the SBP shall be to achieve and maintain domestic price stability,

followed by financial stability and support for the general economic policies of the Government for fostering

development and fuller utilization of Pakistan’s productive resources (Preamble, Section 4B). Here price stability

is defined as the maintenance of low and stable inflation guided by the government’s medium-term inflation target.

As per the previous preamble, the SBP’s mandate was to secure monetary stability and fuller utilization of the

country’s productive resources whereas Section 4 is a new addition to the SBP Act.

(ii) Prohibition on Government borrowing: The SBP shall not extend any direct credits to or guarantee any

obligations of the Government, or any government-owned entity or any other public entity, barring government

or publicly owned bank and other regulated entities (Section 9C). In practice, since July 2019, the Government has

not borrowed directly from the SBP.

(iii) Discontinuation of quasi-fiscal operations: The SBP shall not undertake any quasi-

fiscal operations

(Section 20, clause 5A), defined as monetary actions taken on behalf of the government. However, it can continue

to extend refinance facilities to financial institutions with appropriate checks and balances and as the lender of last

resort, provide temporary liquidity facilities to banks against appropriate collateral (Section 18, Clause 1A and

Section 20, clause 17G).

(iv) Financial resources: To facilitate smooth functioning and the achievement of its objectives, the SBP’s authorized

and paid-up capital has been increased from a total of PKR100 million to PKR500 billion (authorized capital) and

PKR100 billion (paid-up capital) (Section 4).

(v) Coordination between the SBP and the Government: The Monetary and Fiscal Policies Coordination Board

has been abolished as its terms of reference overlap with the MPC’s mandate. Instead, the Finance Minister and

SBP Governor will establish a close liaison and keep each other informed of matters that jointly concern the

Ministry of Finance and the SBP (Section 9G).

(vi) Protection of SBP officials: In line with international best practices, the amendments provide protection to SBP

employees and officers from any legal proceeding for actions taken in good faith (Section 52A).

(vii) Executive committee, consisting of the Governor and the Deputy Governors, Executive Directors and other

officers will be responsible for formulating policies related to the SBP’s core functions as well as those related to

23

The SBP had maintained the policy rate at 7.0 since June 2020 to mitigate the pandemic-associated economic downturn.

24

Average CRR to be maintained by scheduled banks for a period of two weeks, was increased from 5 percent to 6 percent and the

minimum CRR to be maintained each day was raised from 3 percent to 4 percent. State Bank of Pakistan, Press Release November 13,

2021.

25

State Bank of Pakistan. Press Release, November 19, 2021.

26

State Bank of Pakistan. Monetary Policy Statement, April 07, 2022.

Financing the Real Economy

Pakistan Development Update

April 2022

The World Bank

7

administration and management matters, excluding those matters falling in the purview of the MPC or the Board

of Directors (Section 9F).

(viii) Accountability to Parliament: The Governor shall submit an annual report before the Parliament regarding the

achievement of the SBP’s objectives, conduct of monetary policy, state of the economy, and financial system

(Section 39).

Other amendments approved pertain to conflict of interest, the appointment of a Chief Internal Auditor and establishment

of an Audit Committee; the appointment of external auditors; and the appointment, terms of office and removal of non-

executive directors of the board, external members of the MPC, and the Governor and Deputy Governors of the SBP.

Source: (a) State Bank of Pakistan Act, 1956 (https://www.sbp.org.pk/about/act/SBP-Act.pdf), (b) Ministry of Finance, Brief on SBP

Amendment Act 2021 (https://www.finance.gov.pk/SBP_Act_2021.pdf and http://www.finance.gov.pk/SBP_Amendment_Act_2021.pdf).

Financial Sector

Financial sector

buffers remain strong

but emerging risks

may

accentuate

vulnerabilities

The banking sector, which accounts for 74.1 percent of the overall financial sector assets,

has remained profitable throughout the

pandemic, and displayed strong sol

vency, with a

capital adequacy ratio (CAR) of 16.7 percent in December 2021

— above

the SBP’s

minimum requirement of 11.5 percent. However, it should be noted that the CAR is at its

lowest since June 2019, which may be attributed to the strong private sector credit growth

witnessed since the start of the pandemic. Unlike lending to the Government, increases in

the private sector lending portfolio may increase the total amount of risk

-

weighted assets,

thereby lowering the CAR.

Additionally, increasing exposure to the sovereign

in a

deteriorating macroeconomic environment means that the health of the banking sector is

deeply intertwined with the Government’s fiscal strength.

NPLs are on a

declining trend and

are well

-provisioned

for

Banking sector asset quality has improved with gross non-performing loans (NPLs) down

from 8.9 percent at end

-June 2021 to 7.9 percent in December 2021.

Along with lower

NPLs, the bank NPL provision coverage ratio has risen to 91.2 percent

—

the highest in

r

ecent history, warding off any immediate stability concerns.

The gains realized in recent

months, however, may

unwind with the increase in the

key policy rate and its associated

cascading impact on floating rate loans.

SBP’s refinancing

facilities

contributed

to

expansion in

private sector credit

Outstanding loans to private sector businesses grew by 15.4 percent in H1 FY22, up from

a growth of 4.5 percent in the same period last year. Credit to the corporate sector

in

creased by 16.7 percent,

whereas that to the SME sector grew 18.3 percent.

Disbursements under the

SBP’s Temporary Economic Refinance Facility

(TERF) and

Long-Term Finance Facility (LTTF) grew 32.7 percent during the same period.

However, banks

continue

to

underdeliver on their

role as a financial

intermediary

to the

private sector

Credit to the public sector was 66.8 percent of all bank credit extended at end-December

2021.

27

Although this appetite for government paper does not pose an

immediate credit

risk to the system, if the sovereign starts to face stress, the

n

credit risks can escalate very

rapidly. At present, the greatest risk of this dependency on lending to the sovereign

remains the continu

ed crowding out of the private sector.

For a more detailed discussion

of the issues faced by the financial sector and opportunities for growth, see Chapter 4.

d. External sector

The CAD widened

sharply in H1

FY22…

The current account registered a deficit of US$9.0 billion in H1 FY22, the largest since

H2 FY18, from a surplus of US$1.2 billion in H1 FY21 (

Figure 2.3

). The expansion of

the CAD was led by a record

-high trade deficit due to the

elevated import bill.

Remittances registered a robust growth of 11.3 percent y

-o-

y in H1 FY22, partially

financing the trade deficit.

27

Includes direct lending to government, lending to state-owned enterprises (SOEs), and investments in government securities

Financing the Real Economy

Pakistan Development Update

April 2022

The World Bank

8

Figure 2.3: H1 Current Account Balances (Jul–Dec)

(US$ billion)

Figure 2.4: H1 Financial Account Inflows (Jul–Dec)

(US$ billion)

Source: State Bank of Pakistan, World Bank staff calculations

Source: State Bank of Pakistan, World Bank staff calculations

Note: A positive financial account balance represents inflows

Figure 2.5: Import of goods and services (Jul–Dec)

(US$ million)

Figure 2.6: Export of goods and services (Jul–Dec)

(US$ million)

Source: State Bank of Pakistan, World Bank staff calculations

Source: State Bank of Pakistan, World Bank staff calculations

…as goods and

services imports

surged, amid higher

domestic demand

and global prices

The overall trade deficit increased from US$12.3 billion in H1 FY21 to US$23.0 billion

in H1 FY22. The increase in the trade deficit reflected sharp increases in both the goods

and services trade accounts. The goods trade deficit widened to US$21.2 billion in H1

FY22 up from US$11.4 in H1 FY21 as goods imports surged by 57.0 percent,

reflecting

growing domestic demand and higher global commodity prices (

Figure 2.5).

Goods

i

mports grew strongly across most categories, particularly petroleum produc

ts, machinery,

transport vehicles, metals, food products, and fertilizers. Using Pakistan Bureau of

Statistics data on goods import quantum and values, around 53 percent of the increase in

total goods imports in H1 FY22 can be attributed to an increase in prices, while the

remaining 47 percent was due to an increase in the quantity imported. For primary goods,

namely soybean oil, palm oil, cotton, crude oil, and petroleum products

–

around 84

percent of the growth in import values was due to the increase in

global prices.

Meanwhile, goods exports grew 28.9 percent on the back of a jump in textile exports,

mainly attributable to increased international orders and recent investments to expand

and modernize the sector (

Figure 2.6).

28,29

Likewise, with services imports growing faster

than services exports, the services trade deficit grew to US$1.8 billion in H1 FY22. This

was mainly driven by a

sharp increase in trade-relate

d transport services imports, due to

higher shipping costs.

30

28

Textile machinery imports grew by 121.6 percent in H1 FY22, compared to a growth of 1.4 percent in H1 FY22.

29

(i) Dawn: https://www.dawn.com/news/1662021/textile-exports-projected-to-cross-20bn-target, and (ii) Bloomberg:

https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2022-01-30/pakistan-s-textile-exports-to-surge-as-orders-move-from-rivals.

30

Review of Maritime Transport 2021, UNCTAD

-4.7

-7.5

-8.7

-10.5

-8.3

-5.1

-3.4

-1.0

1.2

-3.2

-9.0

-30

-20

-10

0

10

20

H1-FY17

H2-FY17

H1-FY18

H2-FY18

H1-FY19

H2-FY19

H1-FY20

H2-FY20

H1-FY21

H2-FY21

H1-FY22

Secondary Income Balance

Primary Income Balance

Services Trade Balance

Goods Trade Balance

Current Account Balance

4.8

5.1

7.0

6.6

6.0

5.8

7.1

2.2

0.3

7.9

10.1

0

5

10

H1-FY17

H2-FY17

H1-FY18

H2-FY18

H1-FY19

H2-FY19

H1-FY20

H2-FY20

H1-FY21

H2-FY21

H1-FY22

Net incurrence of financial liabilities

Net acquisition of financial assets

Portfolio investment

Direct investment

Financial Account Balance

23.2

36.4

3.8

5.3

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

35

40

45

H1 FY21 H1 FY22

US$ Billion

Imports of goods FOB Imports of services

54.4

percent

11.8

15.2

2.8

3.4

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

35

40

45

H1 FY21 H1 FY22

US$ Billion

Exports of goods FOB Exports of services

27.3

percent

Financing the Real Economy

Pakistan Development Update

April 2022

The World Bank

9

The income account

recorded a

marginally higher

surplus in H1 FY22

The overall income account surplus increased by 3.0 percent y-o-y to US$14.0 billion in

H1 FY22. Within the income account,

the primary income account deficit decreased by

7.2 percent in H1 FY22, supported by debt service relief under the G20 Debt Service

Suspension Initiative (DSSI), which was extended till December 2021. The secondary

income account surplus increased marginally by 1.3 percent as well, as remittances, the

largest contributor to this account, increased to US$15.8 billion in H1 FY22 up from

US$14.2 billion in H1 FY21.

31

The financial

account recorded a

large surplus due to

a

significant inflow

of fresh loans

The financial account saw net inflows of US$10.1 billion in H1 FY22, compared to

US$0.3 billion in H1

FY21 (Figure 2.4). The increase was driven by inflows

from the IMF

as per the revised SDR allocation, a Eurobond issuance

in July 2021, and short-

term

government deposits from Saudi Arabia. Pakistan also made a repayment

of

US$1.0

billion against a previous Sukuk issuance in October 2021, which led to overall portfolio

outflows of US$0.4 billion in H1 FY22. Meanwhile, at US$1.0 billion, FDI inflows

remained significantly below pre

-pandemic levels, partly reflecting protracted uncert

ainty

in international markets

regarding the global economic outlook.

The surplus in the overall

balance of payments

declined from US$1.3 billion in H1 FY21 to US$0.8 billion in H1

FY22, due to the wider CAD.

The CAD has

widened

further in

recent

months,

increasing external

sustainability risks

The CAD in January 2022 reached a monthly high of US$2.5 billion – as imports

continued to increase sharply but narrowed to US$0.5 billion in February as measures

taken by the Government to curtail non

-essential imports

, higher prices and the weaker

Rupee

began to take effect. Cumulatively, the CAD in Jul–

Feb FY22 was recorded at

US$12.1 billion, compared to a surplus of US$1.0 billion in the same period in FY21. In

January

-February 2022, Pakistan received

inflows of US$1.0 billion against an

International Sukuk issuance

and US$1.1 billion from the IMF

, taking net financial

inflows

in Jul–Feb FY22 to US$12.1 billion. Despite these inflows,

foreign exchange

reserves

fell to US$12.9 billion at end-March 2022,

the lowest since June 2020, and

equivalent to 1.9 months of imports of goods and services.

32,33

Increased current

account pressures

and elevated political

uncertainty

contributed to the

Rupee’s depreciation

After appreciating by 6.9 percent in FY21, the Rupee depreciated by 14.3 percent against

the

U.S. dollar from July to end-March 2022,

34

in part due to pressures from the rising

import bill

, policy normalization among advanced economies, safe-

haven effects

associated with the Ukraine war, and domestic political uncertainty

. Meanwhile, Pakistan’s

Real Effective Exchange Rate (REER)

depreciated by 3.0 percent between Jul-

Feb

FY22.

35

e. Fiscal and Debt Sustainability

Pakistan’s fiscal

deficit widened

The consolidated fiscal deficit reached PKR1,372 billion in H1 FY22 from PKR1,138

billion in H1 FY21

– an increase of 20.6 percent y-o-

y. Higher taxes on imported items

and sales tax on goods led to an 18.0

-percent growth in revenue

s, but this was outweighed

by higher government

spending, which grew 18.7 percent (Figure 2.7).

With most of the

increase in spending coming from non

-interest expenditures,

the primary surplus shrank

to PKR81 billion.

In H1 FY22, all provinces except for Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KP)

recorded a surplus leading to a consolidated

provincial surplus of PKR481 billion, a

lmost

double of that a year ago.

However, a sharp increase in federal current expenditure

led to

a 33.0

-percent increase in the federal fiscal deficit –

leading to the wider consolidated

fiscal deficit.

31

Remittances from E.U. countries increased by 37.8 percent, the United States by 24.0 percent, the United Kingdom by 14.4 percent, the

UAE by 1.8 percent), and other GCC countries by 11.7 percent in H1 FY22.

32

However, part of the decline in reserves is expected to be reversed in the coming weeks as official creditors rollover their loans.

33

Based on the next 12 months’ projected imports of goods and services.

34

Calculated using end period exchange rates (for June 2021 and March 2022). International Financial Statistics, International Monetary

Fund.

35

Real Effective Exchange Rate based on Consumer Price Index. Ibid.

Financing the Real Economy

Pakistan Development Update

April 2022

The World Bank

10

Figure 2.7: Consolidated Fiscal and Primary Balance

(excluding grants) in H1

(PKR billion)

Figure 2.8: Budgetary Financing: Net External and

Domestic Inflows in H1

(PKR billion)

Source: Ministry of Finance, World Bank Staff Calculations

Note: Other federal current expenditure includes subsidies.

Taxes on imports

drove the overall

increase in tax

revenues

in H1 FY22

In H1 FY22, tax revenues grew 19.2 percent y-o-y, up from a growth of 12.0 percent in

H1 FY21.

The higher

taxes collected on imported items were due to a combination of

higher global

prices, and a larger volume of imports.

36

The three largest contributors to

growth in revenues in H1 FY22 were sales tax on goods, direct taxes, and taxes on

international trade/c

ustoms duties.

Of the revenues collected by the Federal Board of

Revenue (FBR), 52.1 percent are related to imports. More specifically, 70 percent of the

sales tax on goods, 13.7 percent of direct taxes and 8.5 percent of the federal excise duty

collected were based on imports.

37,38

Non-tax revenues

recovered in H1

FY22

After declining by 23.2 percent in H1 FY21, non-tax revenues increased by 12.6 percent

in H1 FY22, largely due to higher inflows from the Pakistan Telecommunication

Authority at the federal level, and higher hydropower profits of KP at the provincial level.

Barring mark

-up payments from Public Sector Enterprises, all other sources of non-

tax

revenues also recorded an increase in H1 FY22.

Federal Government

current

spending

rose sharply in H1

FY22

, in part due to

vaccine procurement

In H1 FY22, current expenditures increased by 16.0 percent y-o-y, up from the 8.3-

percent growth in H1 FY21. Development expenditures and net lending also rose by 24.8

percent, after declining by 3.3 percent in H1 FY21. The highest contribution to growth

in current expenditure came from grants and subsidies. This was in part due to

procurement of COVID

-19 vaccines by the Federal Government –

an expense recorded

under grants

–

and settlement of outstanding power sector arrears, recorded under

subsidies.

39

As part of reforms to increase domestic revenues

, the Government approved

a Supplementary Finance Bill in January 2022,

withdrawing two-thirds of tax exemptions

on GST (Box 2.2).

36

With the rise in global prices, taxes collected on imported items such as petroleum products, vehicles, edible oils, and machinery grew

significantly, whereas, for cotton and fertilizer, higher demand bolstered tax revenues as the quantum of imported items increased in H1

FY22. Bi-Annual Review. Jul-Dec 2021-22. Federal Board of Revenue

37

The revenue generated by the FBR is 88.6 percent of the total tax revenue and includes direct taxes, sales tax on goods, federal excise

duty, and customs duty on imports. Historically, the share of taxes generated through imports has been lower than domestically sourced

taxes (44.3 percent at end-FY21). Ibid

38

Revenue from direct taxes rose by 22.7 percent in H1 FY22 – the highest half-year growth since FY12 – as revenue from withholding

taxes on imports grew 45.5 percent. Ibid.

39

In H1 FY22, the Federal Government settled PKR135 billion in debt owed to Independent Power Producers (IPPs) and spent PKR196.3

billion on COVID-19-related spending under grants. See: Ministry of Finance: Monthly Economic Update & Outlook: February 2022.

-799

-796

-1030

-995

-1138

-1372

-152

-45

-153

286

337

81

-1400

-1200

-1000

-800

-600

-400

-200

0

200

400

FY17 FY18 FY19 FY20 FY21 FY22

Fiscal Balance Primary Balance

0

200

400

600

800

1000

1200

1400

FY17 FY18 FY19 FY20 FY21 FY22

Net domestic inflows (non-bank financing)

Net domestic inflows (bank financing)

Net external inflows

Financing the Real Economy

Pakistan Development Update

April 2022

The World Bank

11

Box 2.2: Finance (Supplementary) Act 2022

The Finance (Supplementary) Act 2022, passed by the National Assembly on January 13, 2022, was introduced to

enhance revenue mobilization, and streamline expenditure in line with the fiscal framework agreed upon in the Sixth Review

of the IMF-Extended Fund Facility (EFF). As per the IMF, the supplementary bill targeted an underlying primary balance

(excluding grants) of 0 percent of GDP in FY22 and a provincial consolidated surplus at 0.5 percent of GDP in FY22.

Expenditure:

The Supplementary Bill aimed to reduce non-priority current spending and poorly targeted subsidies, while

making provisions for higher spending on the procurement of COVID-19 vaccines and clearance of power sector arrears. It

also budgeted for an increase in development expenditure and social spending, mainly through 1) expansion of the Benazir

Income Support Program by 50 percent (excluding COVID-19 related one-off spending); 2) increase in health and education

spending by 27 percent; and 3) spending on the Kamyab Pakistan Program and food subsidy program (estimated at 0.2 percent

of GDP).

Revenue: The revised fiscal program focused on eliminating two-thirds of tax expenditures on GST while broadening the tax

base and improving tax administration. The Supplementary Bill also budgeted for a gradual increase in the PDL until it reached

a maximum of PKR30/liter. However, with the fuel price reduction package announced in February, past increases in the PDL

were most likely partially or wholly reversed and further increases were temporarily paused.

40

The table below summarizes the

main legislative amendments made as part of the supplementary bill.

General Sales Tax: Amendments to Sales Tax Act 1990

Streamlining of

tax rates

Fifth schedule: Zero-rating withdrawn on several items including duty-free shops; local supply of

plant and machinery to export processing zones and exports, covered under the Export Facilitation

Scheme; and the supply, repair, or maintenance of ships and related equipment and machinery. In

contrast, zero-rating was introduced on drugs at the import stage and reinstated for crude oil.

Eighth schedule: Several goods with reduced rates of tax have been brought under the standard GST

regime, including branded food items; agricultural machinery and other inputs, such as poultry and

cattle feed; plant and machinery not manufactured locally and having no compatible local substitutes;

internet and TV broadcast equipment; and silver, gold, and precious metal jewelry.

Eliminating

exemptions

Sixth schedule: Exemptions were withdrawn on the following imported and branded items (Table 1

of Sixth Schedule): 1) live animals and poultry, 2) meat and uncooked poultry, 3) eggs, 4) cereals and

milling industry products except for rice, wheat, and wheat and meslin flour, 5) sugar cane, 6) food for

infants, 7) seeds and various types of agriculture equipment, and 8) plant and machinery of greenfield

industries. However, exemptions were retained on imported fruits and vegetables from Afghanistan;

exemptions were withdrawn for local supplies of raw cotton, whey, sausages (sold without retail

packaging), bread and related items sold in tier-1 retailers, and matchboxes, among other items (Table

2 of the sixth schedule).

Increasing tax

rates

Ninth schedule: 17 percent ad valorem tax was introduced on imported mobile devices exceeding

US$200 in value.

Lowering of

threshold

The sales tax threshold for the cottage industry was reduced from PKR10 million in annual turnover

to PKR8 million, to broaden the tax base.

Federal Excise Duty: Amendments to Federal Excise Act 2005

Increasing tax

rates

FED was increased on imported and locally manufactured vehicles.

Previous FED

Current FED

Imported motor cars

Range (2.5–30

percent)

Range (2.5–40

percent)

Locally manufactured or assembled cards

Range (0–5 percent)

Range (2.5–10

percent)

Imported double-cabin pick-up vehicles

25 percent

30 percent

Locally manufactured double-cabin pick-up

vehicles

7.5 percent

10 percent

Customs Duty: Amendments to Customs Act 1969

Administrative

reforms

Under the Finance Supplementary Act 2022, the role of Collector of Customs in determining the

customs value of imported or exported goods was eliminated, and the power to determine customs

value now rests solely with the Director of Customs Valuation. Previously, both the Collector of

Customs and the Director Valuation were authorized to determine the customs value of imported or

exported goods. (Section 25A of the Customs Act).

Income Tax: Amendments to Income Tax Ordinance, 2001

40

In February 2022, the Government announced an energy price reduction package to be implemented from March through June 2022 that

included a reduction of PKR10/liter on end-consumer petrol and diesel prices, a temporary price cap on fuel prices, and a PKR5/unit

subsidy on the base electricity rate for almost 85 percent of domestic consumers and 40 percent of commercial consumers.

Financing the Real Economy

Pakistan Development Update

April 2022

The World Bank

12

Introducing

advance taxes

Advance tax rate was introduced on foreign TV serials and advertisements. Dividends received by the

Real Estate Investment Trust (REIT) from a special purpose vehicle will be taxed at the rate of zero

percent, and dividends paid to non-REIT investors will be taxed at 35 percent.

Source: (i) The primary balance target is excluding grants, one-off transactions, COVID-19 spending, and IPPs related arrears clearance in

FY22. IMF Country Report No. 22/27, (ii) Finance (Supplementary) Act 2022, (iii) The Sales Tax Act, 1990: As amended up to 15

th

January

2022, (iv) FBR Circular No. 01 of 2022, (v) FBR Circular No. 06 of 2022, (vi) FBR Circular No. 12 of 2022.

The fiscal deficit was

largely financed from

external sources

External financing inflows more than doubled in H1 FY22, whereas domestic financing

inflows contracted by

around half

. The growth in net external inflows largely stemmed

from other loans and project aid. Overall, external financing flows constituted 74.8

p

ercent of total budgetary financing in H1 FY22, increasing exchange rate risks

on

external debt (Figure 2.8).

Public debt

increased in H1

FY22

Public and publicly guaranteed debt stood at PKR45.3 trillion at end-December 2021, an

increase of PKR3.1 trillion since end

-June 2021. Of the total public debt at end-

H1 FY22,

the share of external debt was 37.5 percent, whereas short

-

term debt was 13.0 percent.

Pakistan’s total debt level is in breach of the Fiscal Responsibility and Debt Limitation

Act (FRDLA) 2005 (amended in 2017) that stipulated a reduction of total public debt to

60 percent of GDP by end

-FY18. Moreover, the

growing arrears of the power sector and

liabilities emanating from commodity operations pose further risks to debt sustainability.

f. Medium-Term Outlook

GDP growth is

projected to slow in

FY22

–FY23 before

strengthening over

the medium term

On the back of recent monetary tightening, high base effects, and stronger inflation, real

GDP growth

is expected to moderate to 4.3 percent in FY22

and then further to 4.0

percent in FY23 as the Government undertake

s fiscal tightening measures to

manage

growing demand pressures and

contain external and fiscal imbalances.

Economic growth

is then projected to recover

slightly to 4.2 percent in FY24 (Table 2.1), supported by

the

implementation of

structural reforms to support macroeconomic stability

and fiscal

sustainability.

Domestic demand

growth is expected

to slow in

the near-

term

Growth in private consumption and private investment is projected to decline in FY22-

F23,

partly due to higher borrowing costs and erosion in real incomes due to elevated

inflation

before strengthening thereafter. Total i

nvestment growth is also expected to pick

up

then as the business environment improves. After being relatively muted in FY21

due

to fiscal restraint and rollback of pandemic

-related

mitigation measures, government

consumption growth is expected to

increase in FY22 and remain high in FY23 on pre-

election spending before moderating in the medium term.

Inflation is expected

to a

verage in the

double

-digits in

FY22

Consumer price inflation is estimated to rise to an average of 10.7 percent in FY22 on

strong domestic demand, higher global commodity prices and a weaker exchange rate.

Price pressures are then expected to gradually ease over the forecast horizon as energy

prices moderate from recent highs and world inflation pressures dissipate.

The CAD is

expected to widen

sharply in FY22

,

heightening

external

sustainability risks

Largely reflecting the surge in imports, the CAD is expected to widen to 4.4 percent of

GDP

in FY22. With monetary tightening

to curtail macroeconomic risks emanating from

the large external imbalance, imports are projected to decline next year before recovering

again in FY24.

As export competitiveness reforms gain traction,

particularly those aimed

at reducing

import tariffs on relevant

intermediates for the export sector, and increased

allocations for export refinance schemes

,

exports are projected to begin recovering in

FY24, the CAD is

consequently expected to narrow to 3.0 percent of GDP.

In addition,

the growth of official remittance inflows is expected to moderate after benefiting from a

COVID-19-induced transition to formal channels in FY21.

The fiscal deficit is

projected to widen in

FY22

The fiscal deficit (excluding grants) is projected to increase to 6.3 percent of GDP in

FY22,

on the back of higher spending on COVID-

19 vaccine procurement, settlement of

energy sector arrears, developmen

t spending, and the recently announced food and

fuel

price

reduction

packages. As the Government rolls back the relief measures and resumes

fiscal consolidation efforts, the fiscal deficit is projected to narrow slightly to 6.1 percent

Financing the Real Economy

Pakistan Development Update

April 2022

The World Bank

13

of GDP in FY23. With the implementation of structural reforms to increase domestic

revenue mobilization, particularly harmonization of the

GST regime

and Personal Income

Tax

(PIT) reform,

the fiscal deficit is projected to improve further to 5.3 percent of GDP

in FY24.

Public debt as a share of GDP is projected to remain high, but g

radually decline

over the medium term, supported by higher GDP growth and declining primary deficits.

However, Pakistan’s v

ulnerability to debt-related shocks will remain elevated

as will the

country’s external financing requirements. To meet these, Pakistan will need the

continued support of its multilateral and bilateral partners and access to international

capital markets. The macroeconomic outlook is predicated on the IMF

–

EFF program

remaining on track.

Table 2.1: Pakistan Macroeconomic Outlook (FY22-24)

1

(Annual percent change unless indicated otherwise)

2018/19

2019/20

2020/21

2021/22e

2022/23f

2023/24f

Real GDP Growth, at constant factor

prices

3.1 -1.0 5.6 4.3 4.0 4.2

Agriculture

0.9

3.9

3.5

3.6

3.2

3.3

Industry

0.2

-5.8

7.8

4.0

3.3

3.8

Services

5.0

-1.3

5.7

4.7

4.5

4.7

Real GDP Growth, at constant market

prices

2

2.5 -1.3 6.0 4.3 4.0 4.2

Private Consumption

5.6

-3.1

6.3

5.5

3.0

3.9

Government Consumption

-1.6

8.4

3.1

6.9

6.0

3.8

Gross Fixed Capital Formation

-11.1

-5.5

6.8

4.4

2.5

4.4

Exports, Goods, and Services

13.2

1.5

4.8

7.1

1.8

2.8

Imports, Goods, and Services

7.6

-5.1

5.5

12.1

-0.7

2.1

Inflation (Consumer Price Index)

6.8

10.7

8.9

10.7

9.0

7.5

Current Account Balance

-4.2

-1.5

-0.6

-4.4

-3.1

-3.0

Financial and Capital Account Balance,

(% of GDP)

3.7 3.2 2.4 5.7 2.9 3.1

Fiscal Balance (excluding grants, % of

GDP)

-7.9 -7.1 -6.1 -6.3 -6.1 -5.3

Debt (% of GDP)

78.0

81.1

76.0

76.0

74.4

72.5