BRIEFING

EPRS | European Parliamentary Research Service

Author: Nicole Scholz

Members' Research Service

PE 646.363 – April 2020

EN

Organ donation and transplantation

Facts, figures and European Union action

SUMMARY

The issue of organ donation and transplantation gained renewed political momentum as one of the

initial health priorities of the current Croatian Presidency of the Council of the EU.

There are two types of organ donation: deceased donation and living donation. Organ

transplantation has become an established worldwide practice, and is seen as one of the greatest

medical advances of the 20th century. Demand for organ transplantation is increasing, but a

shortage of donors has resulted in high numbers of patients on waiting lists.

Medical, legal, religious, cultural, and ethical considerations apply to organ donation and

transplantation. In the EU, transplants must be carried out in a manner that shows respect for

fundamental rights and for the human body, in conformity with the Council of Europe's binding

laws, and compliant with relevant EU rules. World Health Organization principles also apply.

Organ donation rates across the EU vary widely. Member States have different systems in place to

seek people's consent to donate their organs after death. In the 'opt-in' system, consent has to be

given explicitly, while in the 'opt-out' system, silence is tantamount to consent. Some countries have

donor and/or non-donor registries.

Responsibility for framing health policies and organising and delivering care lies primarily with the

EU Member States. The EU has nevertheless addressed organ donation and transplantation through

legislation, an action plan and co-funded projects, and the European Parliament has adopted own-

initiative resolutions on aspects of organ donation and transplantation.

Stakeholders have submitted a joint statement on a shared vision for improving organ donation and

transplantation in the EU. An evaluation of the EU's action plan identified the need for a new,

improved approach. Innovative products and procedures, such as artificially grown organs and 3D

bio-printing, might lend themselves as future possibilities to reduce our reliance on organ donors.

In this Briefing

Bolstering cooperation to save lives

Organ donation and transplantation basics

EU policy and action

International and European organisations

Stakeholders' views

Looking ahead

EPRS | European Parliamentary Research Service

2

Glossary

Donor after brain death (DBD): a deceased donor for whom death has been determined by neurological

criteria. Also referred to as deceased heart-beating donor.

Donor after circulatory death (DCD): a deceased organ donor for whom death has been determined by

circulatory and respiratory criteria. Also referred to as deceased non-heart-beating donor.

Living donor: a living human being from whom cells, tissue or organs have been removed for the purpose of

transplantation.

Transplantation: the transfer (engraftment) of human cells, tissues or organs from a donor to a recipient with

the aim of restoring function(s) in the body. When transplantation is performed between different species (for

instance, animal to human), it is referred to as xenotransplantation.

Source: Global Glossary of Terms and Definitions on Donation and Transplantation, WHO; Newsletter

Transplant 2019, EDQM/Council of Europe.

Bolstering cooperation to save lives

The issue of organ donation and transplantation is back on the political agenda. As one of the initial

health priorities of the current Croatian Presidency of the Council of the EU, it was included in the

18-month 'trio' programme prepared by the current and two preceding presidencies (Romania and

Finland), which noted that 'cooperation in the field of transplantation and organ donation at EU

level can be strengthened to save lives'. The Croatian Presidency stated in its

programme that, based

on Croatia's positive experience with organ donation and transplantation, it would make 'special

efforts to explore the possibilities of closer and improved cooperation among Member States'.

Organ donation and transplantation basics

Organ donation can be defined as the act of giving one or more organs (or parts thereof), without

compensation, for transplantation into someone else. There are two types of organ donation:

deceased donation and living donation. This means that donated organs come from either a

deceased or a living donor, giving rise, respectively, to deceased-donor and living-donor

transplants. There are two categories of deceased donor: those where donation takes place after

brain death and those where it takes place after circulatory death (see Glossary). The objective of

organ donation is to greatly enhance – or save – the life of the person who receives the transplanted

organ; organ transplantation is often the

only treatment for end-stage organ failure, such as liver

and heart failure. Since the first successful kidney transplant in the United States in 1954, organ

transplantation has become an established worldwide practice considered to be one of the 20th

century's

exceptional medical advances. Demand for organ transplantation is increasing, but there

are not enough organs available to meet the need. Shortage of donors is considered to be a major

limiting factor in treating patients with chronic organ failure, and has resulted in long waiting lists

for patients.

Ethical considerations and fundamental human rights

There are a number of medical, legal, religious, cultural and ethical considerations associated with

organ donation and transplant. In addition to being a life-saving practice, organ donation is often

regarded as an expression of human solidarity. It is considered to be consistent with

the beliefs of

most major religions, including Roman Catholicism, Islam, most branches of Judaism and most

Protestant faiths. According to the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS), research has shown

that, unless a religious group has taken action to prohibit organ donation and transplantation, it is

assumed that such donation is permissible: 'Donation is encouraged as a charitable act that saves or

enhances life; therefore, it requires no action on the part of the religious group. Although this is a

Organ donation and transplantation

3

passive approach to affirming organ and tissue donation and transplantation, it seems to be the

position of a large population of the religious community'.

According to the Council of Europe's Guide to the quality and safety of organs for transplantation

,

the handling and disposal of human organs must be carried out in a manner that shows respect for

fundamental rights and for the human body. Moreover, ethical standards of all aspects of organ

donation and transplantation must conform to the

Oviedo Convention on Human Rights and

Biomedicine and the Additional Protocol on the transplantation of organs and tissues of human

origin (see the Council of Europe section below). EU Member States must also comply with the

relevant EU rules (see below under EU policy and action). As the Council of Europe's guide notes,

other important guidelines to be respected from an ethical point of view include the WHO Guiding

Principles on Human Cell, Tissue and Organ Transplantation and the Declaration of Istanbul on

organ trafficking and transplant tourism (see

World Health Organization). A 2012 review article on

international practices of organ donation highlights the following main points: deceased donation

rates vary markedly around the world; living donation is the mainstay of transplantation in many

countries; many of the unacceptable transplantation practices stem from the exploitation of

vulnerable living donors; and all developments in donation should have equity, quality, and safety

at their core.

Donation and transplantation activity in Europe

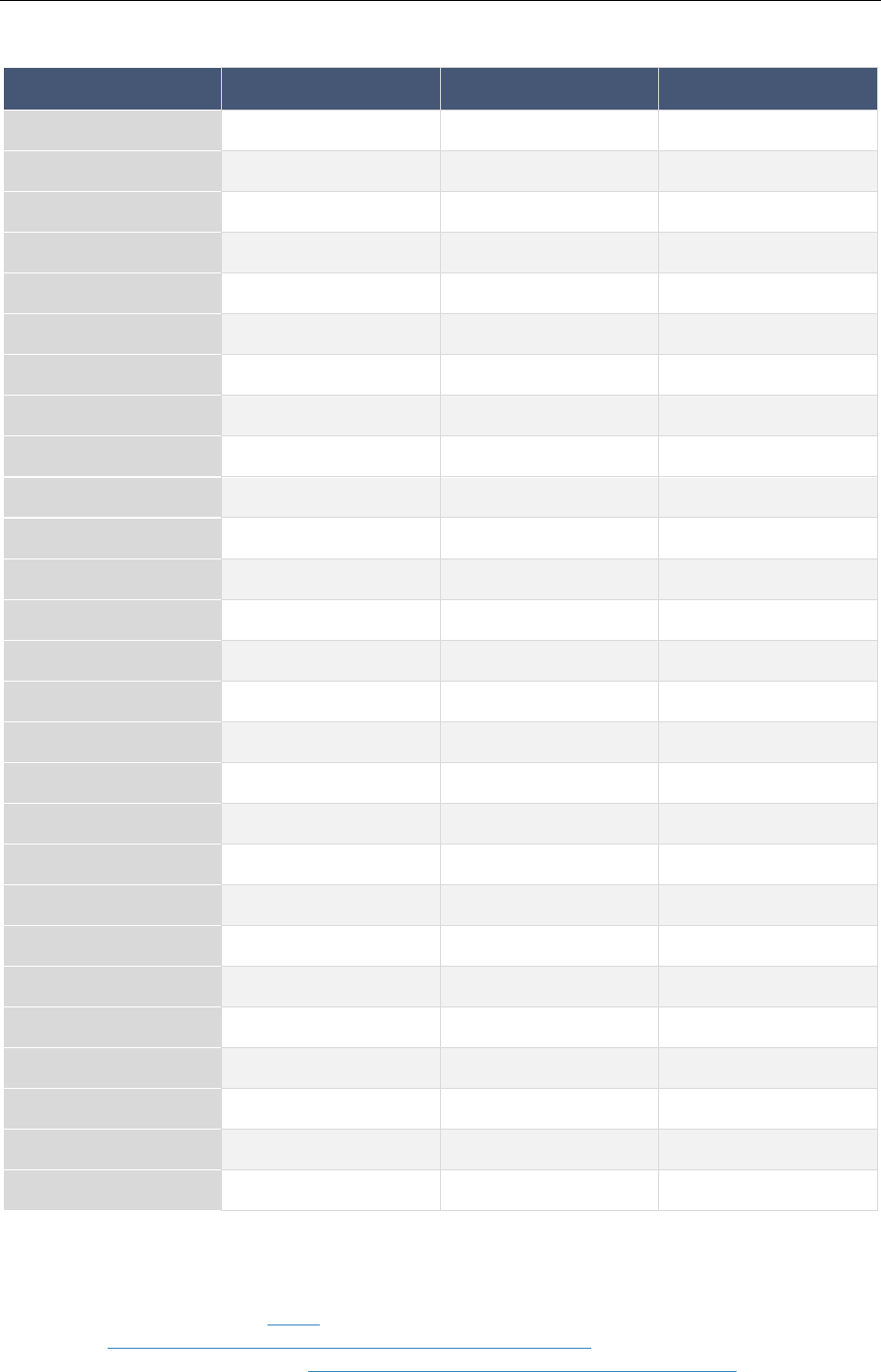

The most frequently transplanted organs in the EU are kidneys (see Table 1). Other commonly

transplanted organs include livers, hearts and lungs. The small bowel and pancreas can also be

transplanted. New types of transplantation are meanwhile being developed all the time.

Table 1 – Number of organs transplanted in 2018 (in 28 EU countries, 509.7 million inhabitants)

Kidney

Liver

Heart

Lung

Pancreas

Small

bowel

Total organs

transplanted

21 227

(19.9 % from

living donors)

7 940

(2.8 % from

living donors)

2 287

1 980

745

42

34 221

Source: Newsletter Transplant 2019, EDQM, Council of Europe.

Nowadays in Europe, the main source of transplantable organs is donations from donors after brain

death, ahead of those from donors after circulatory death and from living donors. According to the

European Commission's 2017

study on the uptake and impact of the EU action plan on organ

donation and transplantation (2009-2015) in the EU Member States, deceased donation is a source

for kidney, liver, heart, lung, pancreas and small bowel transplants. Living donation is mainly

performed for kidney transplants and some liver transplants. Demand for organs exceeds the

number of organs available. In 2018, over

150 000 patients in Europe were registered on organ

waiting lists. Organ donation rates for both deceased and living donation vary widely across the EU.

In 2018, the number of actual deceased donors

1

ranged from 48.3 per million people in Spain, 40.2

per million in Croatia and 33.4 per million in Portugal, to 0.5 per million in Romania (see Figure 1).

Living organ donation practices vary, too. In a 2013 online survey

, large discrepancies were found

between geographical regions of Europe (eastern, Mediterranean and north-western).

EPRS | European Parliamentary Research Service

4

Figure 1 – Actual deceased organ donors 2018 (annual rate per million population)

Data source: Newsletter Transplant, EDQM, Council of Europe. Graphic by Samy Chahri, EPRS.

Consent systems: Opting in versus opting out

EU Member States have differing national (and sometimes regional) systems enabling people to

consent to donating organs after death. Under the 'opt-in' system (also called 'explicit consent' or

'informed consent' system), consent has to be given explicitly. The 'opt-out' system endorses the

principle of 'presumed consent' (silence being tantamount to consent) unless a specific request for

non-removal of organs for donation is made before death. There are also mixed systems. Some

countries have developed donor and/or non-donor registries where citizens can record their wishes

in this regard (see Table 2). In practice, operational variations

exist, as the family of the deceased still

plays a prominent role in the decision-making. The opt-out system is often considered to be a

contributing factor to higher donation rates. Increasing organ donation by adopting an opt-out

system is widely debated among the public and politicians. In this context, a recent

study comparing

opt-in and opt-out systems in 35 similar countries registered with the Organisation for Economic

Co-operation and Development (OECD) found no significant difference in deceased-donor rates; a

reduction in living-donor numbers in the opt-out countries was nevertheless observed. The authors

suggest that 'other barriers to organ donation must be addressed, even in settings where consent

for donation is presumed', and conclude that 'greater emphasis on education and informing the

general population about the benefits of transplantation is the preferred way to achieve an increase

in organ donation'. In this context, a 2016

commentary looks at whether the concept of 'nudging'

deceased donation through an opt-out system constitutes a libertarian approach or manipulation.

Organ donation and transplantation

5

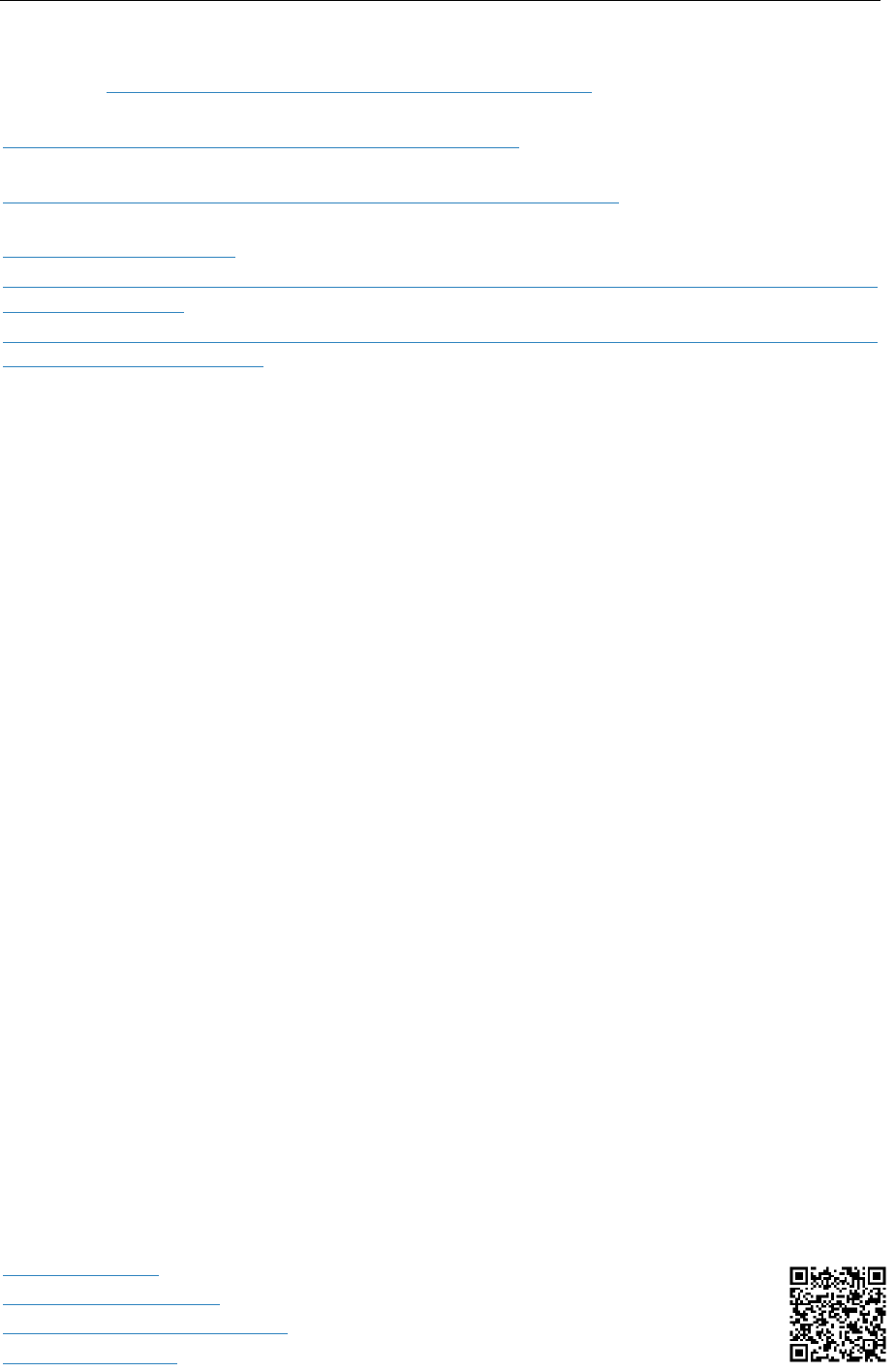

Table 2 – Opting in versus opting out: organ donation from deceased persons in the EU

Country

Consent system

Donor registry

Non-donor registry

Austria

opt-out

x

Belgium

opt-out

*

x

Bulgaria

opt-out

x

Croatia

opt-out

x

Cyprus

opt-in

x

Czechia

opt-out

x

Denmark

opt-in

x

x

Estonia

opt-out

x*

x*

Finland

opt-out

n/a

n/a

France

opt-out

x

Germany

opt-in

Greece

opt-out

x

Hungary

opt-out

x

Ireland

opt-in

n/a

n/a

Italy

opt-out

x

x

Latvia

opt-out

x

x

Lithuania

opt-in

x

*

Luxembourg

opt-out

n/a

n/a

Malta

opt-out

x

Netherlands

opt-in

x

x

Poland

opt-out

x

Portugal

opt-out

x

Romania

opt-in

x

Slovakia

opt-out

x

Slovenia

mixed system

x

x

Spain

opt-out

x

x

Sweden

opt-out

x

x

n/a: data not available.

Note: Spain has an advanced directives registry where persons can register their desire (or otherwise) to

become an organ donor after death.

* th

e data regarding the existence of (non-)donor registries taken from the data source for this table differ

from the results of a 2019 EDQM survey

.

Data source: Guide to the quality and safety of organs for transplantation, EDQM, Council of Europe, 2018 (as

adapted from the Commission's 2017 study on the uptake and impact of the EU action plan).

EPRS | European Parliamentary Research Service

6

EU public opinion on organ donation and transplantation

A 2009 Special Eurobarometer survey on behaviours and attitudes in relation to organ donation and

transplantation showed that the majority of EU citizens supported organ donation, with 55 %

expressing their willingness to donate their own organs after death, and 53 % willing to consent to

donate organs of deceased close family members. According to the survey

report, distrust of the

system (either the transplantation system, the consent system, and/or general social system) and

fear of manipulation of the human body were the main reasons for people not wanting to donate

their own organs or those of a deceased

close family member. More specifically, the

results showed that some 40 % of EU

citizens had talked about organ donation

and transplantation with their family (as

explained in the report, discussion of this

topic within families correlated positively

with support for organ donation). Support

levels for organ donation were generally

higher in the countries that joined the EU

before 2004 than in those that joined after

2004. Education level was also noted as a

key factor influencing support for organ donation. This factor interlinked with several others,

including the fact that certain age groups and regions of Europe that had more limited access to

higher education tended to have lower levels of discussion, awareness and support for organ

donation. Finally, financial hardship and self-described social position appeared to be a barrier to

support for organ donation. Respondents who reported having difficulty paying bills were less likely

to discuss organ donation with their families, or to give their consent to donation, compared to

those who hardly ever experienced this difficulty. Similarly, respondents who ranked themselves

lower on the social ladder were less likely to discuss this topic or to give their consent than those

who gave themselves a higher social ranking.

EU policy and action

The European Parliament has adopted own-initiative resolutions on various aspects of organ

donation and transplantation. In its 2008 resolution on policy actions at EU level, Parliament

considered that the main challenge facing EU Member States with regard to organ transplantation

was to reduce the organ and donor shortage. The resolution stressed that one highly effective way

to increase organ availability was to provide the public with more information. It proposed

establishing a 24-hour transplant hotline with a single telephone number managed by a national

transplantation organisation, to provide rapid, relevant and accurate information. It also called for

the introduction of a European donor card, complementary to existing national systems, and

recognised the need to reduce transplant risks. In its 2012 resolution on voluntary and unpaid

donation of tissues and cells, Parliament stressed, among other things, the importance of non-

remuneration, consent, and protection of living donors' health, underlining the need for anonymity,

traceability and transparency. It called on Member States to step up their information and

awareness-raising campaigns to promote the donation of tissue and cells, and to ensure the

provision of clear, fair and scientifically based medical information enabling the public to make

informed choices. It also asked for reinforced exchange of best practice and strengthened

cooperation. In its 2013 resolution on organ harvesting in China, Parliament expressed its concern

at reports of systematic, state-sanctioned organ harvesting from non-consenting prisoners of

conscience in the People's Republic, and called for the EU and its Member States to raise the issue

in China.

Denmark: from motivation to acceptability

A 2016 survey of public attitudes towards organ

donation in Denmark identified a shift over the

previous three decades from marked opposition to

organ transplantation to strong support for it. The

authors called for

comparative studies in other

countries to generate a better overall understanding of

the conditions of acceptability that needed to be in

place to ensure the long-term social robustness of

organ donation.

Organ donation and transplantation

7

The main responsibility for shaping health policies and organising and delivering care lies primarily

with the EU Member States. The EU has however addressed the issue of organ donation and

transplantation through legislation, an action plan and co-funded projects.

The EU can adopt measures setting high quality and safety standards for substances of human

origin, such as blood, organs, tissues and cells (Article 168

of the Treaty on the Functioning of the

EU). EU rules on organ donation and transplantation are set out in Directive 2010/45/EU (the

'European Organs Directive'). This directive lays down the quality and safety standards for organs

intended for transplantation, covering all stages of the process – from donation, procurement and

handling to transplantation.

Commission Directive 2012/25/EU regarding information procedures

for the cross-border exchange between Member States of human organs intended for

transplantation helps to implement the European Organs Directive. National

competent authorities

are responsible for implementing the requirements established by EU legislation. The European

Commission holds regular

meetings with these authorities to facilitate the exchange of best

practice. Moreover, the competent authorities occasionally adopt statements on topics of common

concern, such as the May 2018

statement on the proposed Global Kidney Exchange concept. As the

Commission has pointed out, experience shows that some organisational models perform better

than others. Identifying those elements that could be promoted at EU level would bring

European

added value, in particular for Member States with less developed organ donation and

transplantation systems. Patients that cannot be adequately treated in small Member States with a

limited donor pool could thereby benefit from EU action.

The EU action plan on organ donation and transplantation (2009-2015) was designed increase organ

availability; enhance the efficiency and accessibility of transplant systems, and improve the quality

and safety of procedures. The Commission's 2013

mid-term review of the action plan found that the

EU Member States had made good progress thus far. The main achievements related to the

increased number and improved training of

donor transplant coordinators, the

introduction or development of living

donation programmes in some Member

States, and improvements in organisational

models. According to the mid-term review,

in the remaining period efforts would be

focused on living donation programmes

and on the cross-border exchange of

organs.

The action plan's mid-term review reflected

the December 2012 Council conclusions

on

organ donation and transplantation:

recalling the main principles and objectives,

the Council acknowledged the Member

States' endeavours to meet the three

challenges set by the action plan. Among

other things, it welcomed the efforts made

to further develop living donation

programmes, the establishment of bilateral

and multilateral agreements between

countries, and the sharing of good practice.

The Council nevertheless saw room for

improvement. It underlined the importance

of transparent and comprehensive

communication to strengthen public trust in

the value of transplant systems, and of

Sharing best practice

Organ donation and transplant medicine is one of the

areas of work of the South-Eastern Europe Health

Network (SEEHN

), a multi-governmental forum for

regional collaboration on health, comprising Albania,

Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Croatia, Israel,

Moldova, Montenegro, North Macedonia, Romania

and Serbia. Within SEEHN, regional health

development centres (RHDC) transform regional

projects into long-term programmes. Headquartered

in Zagreb, Croatia, the

RHDC on organ donation and

transplantation supports cooperation within SEEHN

countries and facilitates the dissemination and

exchange of good practice.

National reform efforts in three leading countries for

organ donation reform – Spain, Croatia and Portugal –

are described in a 2013 paper on

international

approaches to organ donation reform. Also of note are

the individual papers on the development of donation

after circulatory death in Spain, and how Spain reached

40 deceased organ donors per million population; the

development of the Croatian model of organ donation

and transplantation; and organ donation: the reality of

an intensive care unit in Portugal.

Among the countries with the highest deceased donor

rates is also Belgium, where transplantation activities

were initiated in the early 1960s.

EPRS | European Parliamentary Research Service

8

encouraging people to become organ donors after death. It invited countries to share expertise on

several topics, such as expanded criteria for donors (for instance, older donors) so as to increase the

number of available organs.

The Commission's 2017 study on the uptake and impact of the EU action plan

found that the action

plan helped countries set a shared agenda in organ donation, facilitated EU-wide collaboration, and

was most effective for actions that were clearly defined and implied tangible changes in organ

donation. According to the study, many Member States expressed the view that the action plan

helped improve their policies on organ donation, and many considered there was a need for a new,

improved action plan (for more on this see '

Looking ahead' below).

In more concrete terms, the study found that the action plan resulted in a considerable increase in

organ donation and transplantation in the EU over its period of implementation. Between 2008 and

2015, the number of organ donors at EU level increased from 12 000 to nearly 15 000 (a 21 %

increase). This surge in donation rates

resulted in 4 600 additional transplant

operations (a 17 % increase). Kidney

transplants accounted for 60 % of the

increase, liver transplants for 24 %, and heart

transplants for 11 %. Significant variations

were nevertheless observed between

Member States, and rates even decreased in

some countries. The study also highlighted

that – despite the overall progress – by the

end of 2015, the demand for organs in the

EU continued to outstrip supply in all

countries, with thousands of people still

waiting for a transplant. Furthermore,

according to the study, the action plan also

showed that the cross-border exchange of

organs played an important role in

optimising the use of the limited number of

available organs. It found that, while the

majority of cross-border exchanges took

place within European organ exchange

organisations (see text box), many Member

States set up direct collaborations by means

of bilateral agreements

on organ exchange,

such as those between Italy and Malta,

2

and

Spain and Portugal.

3

Cross-border

agreements enabled some countries to

become more specialised in specific

transplantation procedures (for instance,

lung transplants for Austria and Belgium) –

an expertise from which other countries

could then benefit.

In the 2009 to 2015 period, several countries also started using a common organ exchange platform

developed in the course of the EU-funded joint action FOEDUS

(facilitating exchange of organs

donated in EU Member States, 2013-2016). The FOEDUS platform makes it possible for allocation

bodies to offer 'surplus organs' (organs that are difficult to match to recipients in their own country),

and inversely, to get access to offers from surplus organs donated in other countries. This often

concerns children.

As of February 2019, 13 countries had access to the exchange platform, and two

countries had applied to join. The most active EU countries in terms of offering organs through the

European organ exchange organisations

Eurotransplant is a non-

profit international

organisation that facilitates the allocation and cross-

border exchange of deceased donor organs. Eight

countries cooperate within Eurotransplant (Austria,

Belgium, Croatia, Germany, Hungary, Luxemburg,

Netherlands and Slovenia), covering a population of

roughly 137 million people. The organisation allocates

more than 7 000 organs per year, and there are about

14 000 patients on waiting lists for a donor organ. In

2019, the percentage of organs exchanged cross-

border was around

21.5 % of all organs transplanted

(see the statistics library for numbers per country).

Scandiatransplant is the organ exchange organisation

for Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, Sweden and

Estonia (associate member). It is owned by the full

member hospitals performing organ transplantation in

these countries, and covers a population of

approximately 28.8 million. Approximately 2 000

patients are transplanted yearly within

Scandiatransplant (see also the transplantation and

waiting list

figures).

The South Alliance for Transplants (SAT) is trans-

national alliance of south-west European countries

aimed at strengthening and implementing

cooperation in the field of organ, tissue and cell

donation. It has five partner countries: France, Italy,

Portugal, Spain, Switzerland and Czechia (observer),

and covers a population of almost 202 million. SAT

accounts for more than half of all organ donors and

nearly half of all transplanted patients in the EU.

Organ donation and transplantation

9

portal are France, Spain and Italy, while the countries transplanting most organs are Italy, Czechia

and France. On average, 15 organs are offered and two transplanted every month.

The EU has provided funding for several other projects in the area of organ donation and

transplantation, both through the third EU health programme

(2014-2020) and its predecessors, and

through Horizon 2020 and previous EU research framework programmes. On the initiative of the

European Parliament, the EU also funded two pilot projects that ended in 2019: EDITH – focusing on

treatment modalities for end-stage kidney disease, along with different organ donation and

transplantation practices, and

EUDONORGAN – a service contract involving training and social

awareness for increasing organ donation in the EU and neighbouring countries. Other recent

examples include

ELAPHARMA, a novel approach to organ preservation before transplantation, and

NORMOPERF, the development of a portable device for the ex vivo preservation and viability

assessment of solid organs (kidney and liver) for transplantation based on a patented technology.

International and European organisations

World Health Organization

In the area of transplantation, the World Health Organization (WHO) works with member states to:

1 provide assistance to ensure effective national oversight of allogeneic and

xenogeneic transplantation activities. This would ensure accountability, traceability,

and appropriate surveillance of adverse events;

2 increase citizens' access to safe

and effective transplantation of

cells, tissues and organs, and

ensure ethical and technical

practices;

3 promote international

cooperation to encourage global

harmonisation of technical and

ethical practices in

transplantation; this would include

preventing the exploitation of the

disadvantaged through transplant

tourism and the sale of human

material for transplantation;

4 encourage donation of human

material for transplantation.

The WHO

explains that transplantation of

human cells, tissues or organs saves lives

and restores essential functions where no

alternatives of comparable effectiveness

exist. The WHO also notes the major

differences between countries in access to

suitable transplantation, and in the level of

safety, quality and efficacy of donation and

transplantation. It emphasises the ethical

aspects of transplantation, cautioning that

transplant shortages and patients' unmet

transplant needs tempt some into

trafficking human body components for

transplantation (see box).

Declaration of Istanbul

The 2008 Declaration of Istanbul on organ trafficking

and transplant tourism was drafted u

nder the

leadership of the Transplantation Society and the

International Society of Nephrology at the end of a

global summit, initiated by the World Health

Organization. It sets out definitions for unethical

practices, such as transplant tourism and organ

trafficking, and lays down

principles to guide

policymakers and health professionals working in the

field. The declaration was

updated in 2018, and now

includes a more succinctly worded set of principles. For

instance:

[…]

3. Trafficking in human organs and trafficking in

persons for the purpose of organ removal

should be prohibited and criminalised.

4. Organ donation should be a financially

neutral act. […]

7.

All residents of a country should have

equitable access to donation and transplant

services and to organs procured from

deceased donors. […]

11. Countries should strive to achieve self-

sufficiency in organ donation and

transplantation.

EPRS | European Parliamentary Research Service

10

The WHO Guiding Principles on Human Cell, Tissue and Organ Transplantation, first endorsed in

1991 and updated in 2010, urge member states, among other things, to:

promote the development of systems for the altruistic, voluntary, non-remunerated

donation of cells, tissues and organs as such from deceased and living donors, and

increase public awareness and understanding of the resulting benefits ;

oppose the seeking of financial gain or comparable advantage in transactions involving

human body parts, organ trafficking and transplant tourism;

promote a system of transparent, equitable allocation of organs, cells and tissues,

guided by clinical criteria and ethical norms, as well as equitable access to

transplantation services in accordance with national capacities;

strengthen national and multinational authorities to provide oversight, organisation

and coordination of donation and transplantation activities, with special attention to

maximising donation from deceased donors and to protecting the health and welfare

of living donors with appropriate healthcare services and long-term follow up.

The WHO operates the Global Knowledge Base on Transplantation

(GKT), a source of information on

organ, tissue and cell donation and transplantation for those involved in the field – from the lay

public, to health professionals and health authorities. The GKT is made up of four components that

are being progressively developed: activity and practices; legal framework and organisational

structure; vigilance, threats and responses; and xenotransplantation. The Spanish national

transplantation agency (Organización National de Trasplantes,

ONT) collaborates with the WHO on

GKT by maintaining a global database with information on organ donation and transplantation

activities derived from official sources, and on legal and organisational aspects. The database can

be accessed via the

Global Observatory on Donation and Transplantation (GODT) website.

Council of Europe

In addition to being an international human rights organisation, the Council of Europe is also a

leading standard-setting institution in the field of organ, tissue and cell transplantation. It has

adopted legally binding texts on the topic, such as the 1997

Oviedo Convention on Human Rights

and Biomedicine and the 2002 Additional Protocol on transplantation of organs and tissues of

human origin to the Oviedo Convention, as well as the 2015 Convention against Trafficking in

Human Organs. Its non-legally binding texts include recommendations– such as those on

xenotransplantation, organ donor registries, organ trafficking, and criteria for the authorisation of

organ transplantation facilities – and resolutions, for instance, on removal, grafting and

transplantation of human substances, and on establishing harmonised national living donor

registries with a view to facilitating international data sharing. Moreover, it issues reports and other

publications on the topic, such as Ethical eye: transplants.

The Council of Europe's work on organ transplantation is coordinated by the European Directorate

for the Quality of Medicines and Healthcare (EDQM

), whose mission is: to ensure human dignity;

maintain and fulfil human rights and fundamental freedoms; guarantee non-commercialisation of

substances of human origin; and protect

donors and recipients of organs, tissues and

cells. Within the EDQM, the European

Committee on Organ Transplantation,

composed of internationally recognised

experts, is in charge of: organ

transplantation activities that promote the

non-commercial donation of organs, tissue

and cells; the fight against organ trafficking;

and the development of ethical, quality and

safety standards in the field of organs,

tissues and cells. It provides

technical guides

European Day for Organ Donation and

Transplantation on 10 October

The Council of Europe's EDQM organises the European

Day for Organ Donation and Transplantation (EODD)

every year to raise awareness of organ, tissue and cell

donation as a way to improve and save lives. The EODD

seeks to encourage public debate on the topic, and

invite health professionals and policy-makers across

Europe to reflect on the importance of this therapy.

The EODD event takes place in a different country

every year. In 2020, the host country is Poland.

Organ donation and transplantation

11

for professionals, including on the quality and safety of both organs for transplantation and tissues

and cells for human application.

4

The Newsletter Transplant, published yearly, contains figures for

organ donation and transplantation across Europe and internationally. The EDQM also issues

booklets for a wider audience, such as on

donation of oocytes (egg cells) or post-transplant health.

The EDQM's 2003 European consensus document 'Organ shortage: current status and strategies for

improvement of organ donation' provides a step-by-step guide to the procurement of high-quality

organs from cadaveric donors, based on scientific data and international experience. The specific

recommendations underline, among other things, the need for an appropriate legal framework for

donation and transplantation that adequately defines brain death, the type of consent or

authorisation required for organ retrieval, and the means of retrieval, ensuring traceability while

maintaining confidentiality and banning organ trafficking.

Stakeholders' views

In October 2019, a number of stakeholders from the organ donation and transplantation community

submitted a joint statement

(updated version – January 2020) on a shared vision for improving

organ donation and transplantation to the European Commission. The statement was the main

output of the 2019 thematic network on improving organ donation and transplantation, led by the

European Kidney Health Alliance (

EKHA). It was developed in conjunction with national competent

authorities for organ donation and transplantation, transplant organisations, medical professionals

and patient associations, and

endorsed by co-signing organisations and Members of the European

Parliament. The policy recommendations made include: i) mobilising political will to make organ

donation and transplantation a priority; ii) improving legal and institutional frameworks; iii)

streamlining organisation and investment in leadership at all levels; iv) allocating appropriate funds

for organ donation and transplantation programmes; v) promoting education and training among

all stakeholders; vi) eradicating inequities in organ donation and transplantation; vii) boosting

benchmarking; and viii) leveraging research.

Looking ahead

As noted in the Commission's 2017 study on the uptake and impact of the EU action plan, many

countries have agreed that future European cooperation is important to promote organ

transplantation, and that EU activities should be continued. The study identified the need for a new,

improved action plan to cover areas such as: communication; education of professionals;

exchange of experiences on minorities and new population groups; end-of-life care; and research.

Innovative products, such

organoids – artificially grown organs that mimic the properties of real

organs – could become a complement to current organ transplantation to restore liver function in

patients with metabolic liver disease. In the near future, organoids may even be transplanted into

people to replace diseased or failing natural organs. According to the European Parliament's Science

and Technology Options Assessment (STOA), producing reliable biological materials on demand

through 3D bio-printing is

an interesting future possibility that might reduce our reliance on organ

donors. In a possible future in which organs are 3D printed, several ethical issues surrounding organ

donation would be resolved: there would be no more dilemmas regarding organ allocation or

scandals due to non-transparent organ distribution by hospitals. The contested field of

xenotransplantation would become obsolete. The psychological problems of patients receiving, for

instance, a heart from a deceased person would no longer be an issue. Human organ smuggling

would become less economically rewarding. In more realistic terms, however, there may be waiting

lists for printed organs, due to limited production capacity and high costs. Moreover, one negative

outcome of the feasibility of organ printing may be that motivation to donate organs would

probably decline and lead to an overall worse situation in terms of

health inequalities for people in

need of an organ (with only those able to afford to pay for their own organs benefiting). Finally, as

the study notes, before bio-printing solid organs becomes routine medical practice, the issue of

whether 3D-printed organs will (or should) be patentable, and what this would mean for patients'

autonomy, needs to be addressed.

EPRS | European Parliamentary Research Service

12

MAIN REFERENCES

Boucher P., 3D bio-printing for medical and enhancement purposes, Scientific Foresight Unit (STOA),

European Parliament, 2018.

Guide to the quality and safety of organs for transplantation, 7th edition, European Directorate for the

Quality of Medicines and Healthcare (EDQM), Council of Europe, 2018.

Guide to the quality and safety of tissues and cells for human application, 4th edition, EDQM, Council of

Europe, 2019.

Newsletter Transplant 2019, Volume 24 (2018 data), EDQM, Council of Europe, 2019.

Organ shortage: current status and strategies for improvement of organ donation – A European

consensus document, EDQM, Council of Europe, 2003.

Study on the uptake and impact of the EU action plan on organ donation and transplantation (2009-

2015) in the EU Member States, European Commission, 2017.

ENDNOTES

1

'Actual deceased organ donors' are donors from whom at least one organ has been recovered for the purpose of

transplantation (in contrast to 'utilised donors', who are donors from whom at least one organ has been transplanted).

2

From 2008 to 2010, 20 organs from Malta were transplanted in Italy.

3

In 2009, 41 organs were offered to Spain from Portugal.

4

For the downloadable versions of both publications, see the 'Main references' section.

DISCLAIMER AND COPYRIGHT

This document is prepared for, and addressed to, the Members and staff of the European Parliament as

background material to assist them in their parliamentary work. The content of the document is the sole

responsibility of its author(s) and any opinions expressed herein should not be taken to represent an official

position of the Parliament.

Reproduction and translation for non

-commercial purposes are a

uthorised, provided the source is

acknowledged and the European Parliament is given prior notice and sent a copy.

© European Union, 2020

.

Photo credits: ©

Csaba Deli / Shutterstock.com.

[email protected]ropa.eu (contact)

www.eprs.ep.parl.union.eu

(intranet)

www.europarl.europa.eu/thinktank

(internet)

http://epthinktank.eu

(blog)