1

Transition to Integration

Research Workforce:

Sylviane N-K Greensword, Rebecca Sharpless, Mary Saffell, Frederick W. Gooding, Jr.,

Marcellis R. Perkins, Kelly Phommachanh, Scott Langston, Cecilia Sanchez Hill, Blake Gandy,

Holly Harris

Introduction

As the survey reports from previous years note, TCU’s Race and Reconciliation Initiative

has adopted a chronological “triangulation” approach to document our institution’s complex, and

sometimes contradictory, relationship with slavery, the Confederacy, and racism. This year’s

research explored TCU’s transition from racial segregation to desegregation. Our study begins

during World War II, when select professors at TCU taught a small number of African American

soldiers off campus, and concludes in 1971, when, in the wake of the U.S. Civil Rights

movement, TCU elected its first Black Homecoming queen. The road to integration at TCU was

long, difficult, and painful for many people. Since its founding, TCU existed in a world of white

supremacy, and in many ways, it reflected that reality rather than combatted it. The university

was a creation of its place, in the South, and of the specific time in the life of the United States

and Texas. Jim Crow laws governed segregation by race. These practices ruled the South, Texas,

Fort Worth – and TCU.

As “desegregation” directly refers to reversing the written rule of racial separation, it may

be useful to define the more nuanced term “integration.” In this report’s context, integration is to

be understood as not only desegregation, but also the physical, cultural, administrative, and

2

academic inclusion of people of color within the TCU community. This narrative will therefore

detail the university’s efforts (and barriers to such efforts) to integrate its student body, its

faculty, its administrative staff, its curriculum and coursework, athletics, and student life.

Furthermore, it will highlight the distinction between how the administrators and campus

community at that time viewed this transition and how we, today, view the issue. Indeed, the

debate of the mid-century was centered on whether and how to end segregation, whereas the

contemporary TCU community’s focus has shifted to the pursuit of integration.

In Year 3, we have incorporated the experiences of many racial and ethnic identities

beyond African Americans; yet it is important to note that both segregation and integration refer

predominantly to the treatment of African Americans, as the latter were the intended targeted

population of such practices. For instance, in 1963, Vice Chancellor for Academic Affairs J.M.

Moudy discussed how the ongoing, explicitly intentional “policy of excluding Negro students

from Texas Christian University” contrasted with TCU’s admission of dark-skinned international

students.

1

Likewise, although this report addresses the long-held exclusion of Tejano/Chicano

students until the 1960’s, students of Asian, Middle Eastern, and Latin American descent, as well

as Native and Indigenous students, appear on several occasions in TCU yearbooks that precede

our 1940-1971 timeframe.

1

Statement by J. M. Moudy, June 7, 1963a, fol. RU16, series 1, box 3, Records of James M Moudy,

“Correspondence 1960-1964,” Special Collections/TCU Archives, Fort Worth, TX.

3

Historical Context

Context: TCU and Race in the Fort Worth community

TCU’s location on the ancestral homelands of the Wichita and affiliated tribes is part of a

pattern of race-related displacement that predates Texas’s statehood. The 1841 raid that “cleared

native Indians out of [the] Fort Worth area” set the foundations of a city that would be

characterized by its racial geography.

2

Postbellum Reconstruction heightened the sense of white

entitlement, as newly freed Blacks were perceived to be too lazy to be successful on their own.

Their freedom made them dangerous, because it was assumed to be paired with “ignorance and

barbarism.”

3

Klan chapters were organized throughout Texas to maintain white rule; as

important, “black codes” were set in place to enforce this rule, especially in matters of

proxemics. As Fort Worth historian Richard Selcer puts it: “The codes applied a variety of civil

and criminal statutes differently to Blacks versus whites, restricting freedoms of movement,

property rights, and labor contracts, to name just a few.”

4

Selcer notes that at the turn of the

century, the second-class status of African Americans “started with where they lived. […] As the

city grew, the Black section was pushed farther out to the east and south of town, jumping the

railroad reservations that marked the southern and eastern edges of the city.”

5

Urban planning thus functioned as geographic racism. The residential pattern of

inequality lingered throughout the twentieth century, as exemplified in the 1947 Ordinance that

2

S. Langston, “Horrific Raid Cleared Native Indians Out of Fort Worth Area. How We Can Honor the Past,” Fort

Worth Star-Telegram, May 22, 2020, NewsBank. https://infoweb.newsbank.com/apps/news/document-

view?p=WORLDNEWS&docref=news/17B1F6C49F044EC0.

3

Francis Richard Lubbock, Six Decades in Texas; Or, Memoirs of Francis Richard Lubbock, Governor of Texas in

War Time, 1861-63. A Personal Experience in Business, War, and Politics (United States: B. C. Jones, 1900), 605.

4

Richard F. Selcer, A History of Fort Worth in Black & White: 165 Years of African-American Life (Denton:

University of North Texas Press, 2015), 42.

5

Selcer, A History of Fort Worth in Black & White, 82-83.

4

prevented roads from connecting the White Ridglea neighborhood to Black Como, leading to the

building of a high brick and barbed-wire fence known as the “Ridglea Wall.”

6

Although the two

communities were only a block apart, the 1960 census revealed that Ridglea was 100% white and

Como 98% Black.

7

In addition to standing as a stark symbol of Como’s racial segregation, the

“wall” hindered Como residents’ ability to access basic public amenities, such as the library,

which was on the Ridglea side.

8

On the Como side of the wall, neighborhood residents have

reported, to this day, frequent flooding due to municipal neglect and poor infrastructure.

9

10

6

Ordinance 2401, 1947, Record Group 2, series I, box 3, Fort Worth Public Library Digital Archive, “Ridglea Wall

Records.” http://www.fortworthtexasarchives.org/digital/collection/p16084coll37/id/17/rec/19

7

Blake Gandy, “‘Trouble Up the Road:’ Desegregation, Busing, and the National Politics of Resistance in Fort

Worth, Texas, 1954-1971,” Master’s Thesis, Texas State University, 2020, 79.

8

Gandy, “‘Trouble Up the Road,’” 80.

9

Christian ArguetaSoto, Fort Worth Report, “‘The City Don’t Care, Man:’ Como Residents Offer Views of Fort

Worth’s Plans to Upgrade Water, Sewer Mains.” April 16, 2022. https://fortworthreport.org/2022/04/16/the-city-

dont-care-man-como-residents-offer-views-of-fort-worths-plans-to-upgrade-water-sewer-mains/; Estrus Tucker,

"Como, Fort Worth, Texas," June 12, 2015, Civil Rights in Black and Brown Interview Database,

https://crbb.tcu.edu/clips/410/como-fort-worth-texas, accessed June 16, 2023.

10

Fort Worth Civil Liberties Union Records, University of Texas at Arlington Libraries. "Concrete wall in the

Como neighborhood of Fort Worth nicknamed the "Ridglea Wall.” UTA Libraries Digital Gallery. 1969. Accessed

July 14, 2023. https://library.uta.edu/digitalgallery/img/10011981

5

Figure 1: Ridglea Wall, 1969

11

Figure 2: The “Ridglea Wall” used fences and signs, such as this “Posted -- No Trespassing -- Keep Out,” to enforce separation

between the mostly white Ridglea neighborhood and the African American Como neighborhood, ca. 1969.

11

Fort Worth Civil Liberties Union Records, University of Texas at Arlington Libraries. "Posted No Trespassing

Keep Out" sign in the Como neighborhood of Fort Worth part of the "Ridglea Wall." UTA Libraries Digital Gallery.

1969. Accessed July 14, 2023. https://library.uta.edu/digitalgallery/img/10011983

6

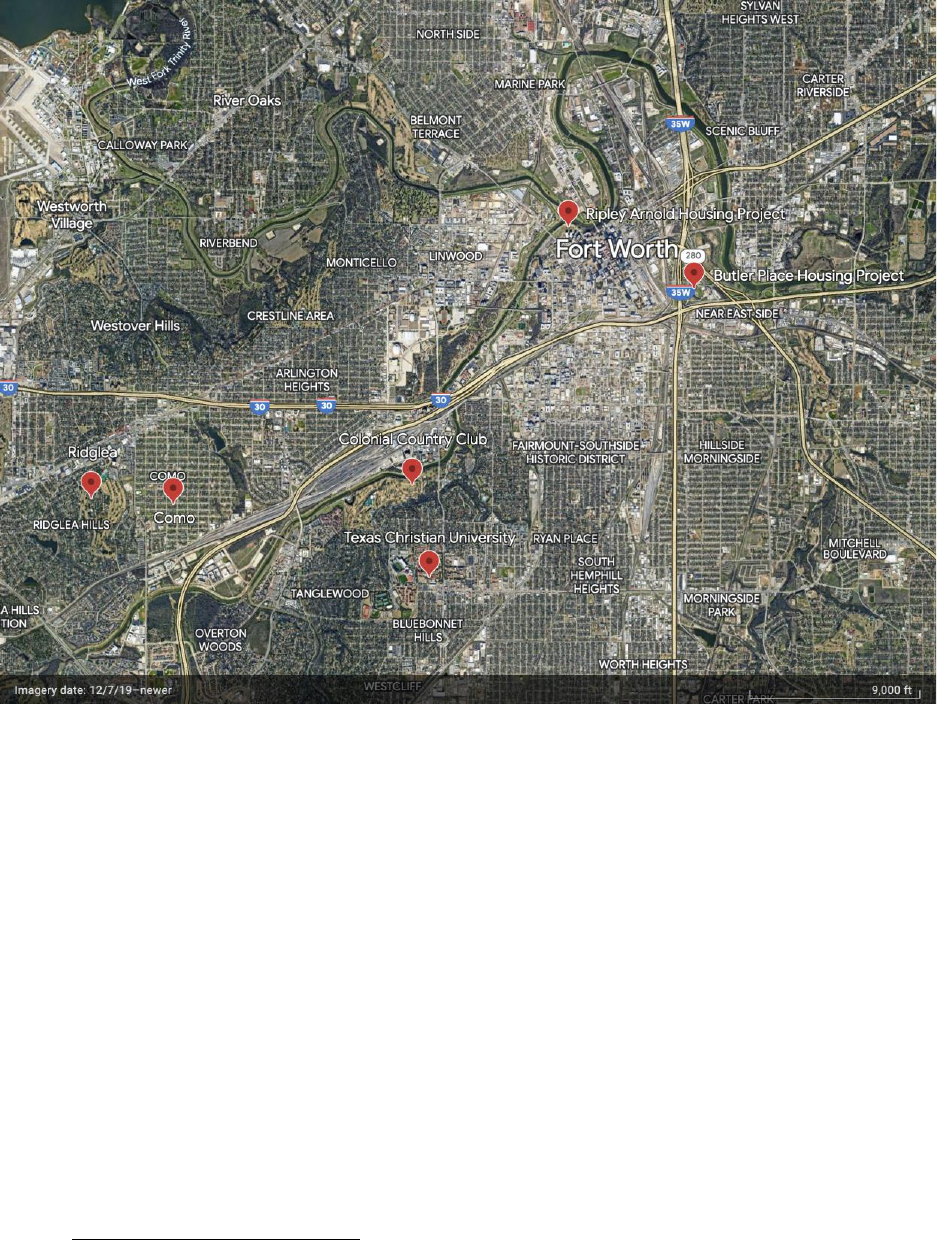

Figure 3: 1969 Westward aerial photograph of the Como neighborhood (on bottom half of photo) and the Ridglea Country Club

Apartments (spanning the center of the photo, from left to right) separated by the Ridglea Wall and Guilford Road (now Bryant-

Irvin Road). Ridglea Country Club is visible on the top left.

12

Despite the highly visible markers of racial divide, the City of Fort Worth was awarded

the All-America City Award in 1964. This recognition honors “communities that leverage civic

engagement, collaboration, inclusiveness and innovation to successfully address local issues,”

and therefore illustrates the extent to which folkways of segregation were ingrained in cultural

norms.

13

Municipal celebrations and festivities were organized in 1965, launched by none other

12

“Exhibit Three,” March 28, 1969, Record Group 2, series I, box 4, Fort Worth Public Library Digital Archive,

“Ridglea Wall Records.” http://www.fortworthtexasarchives.org/digital/collection/p16084coll37/id/147/rec/6

13

National Civic League. https://www.nationalcivicleague.org/america-city-award/.

7

than the TCU Horned Frog band. Although the university had recently begun its transition to

integration, the public portrayal of its student body did not include anyone of color.

14

Figure 4: TCU band performing at the All-America City parade. Original caption reads“Members of the Texas Christian

University Horned Frog band step out to launch Fort Worth's All America City parade. Thousands of people lined the downtown

parade route.” May 17, 1965.

The neighborhood around Ridglea Country Club was not alone in engaging in explicit

practices of segregation. TCU’s immediate neighbor, Colonial Country Club, opened in 1936 as

a “men only” establishment. The Colonial would not admit its first Black member until more

than five decades later, after brokering an agreement with the Fort Worth Chamber of

Commerce. The change was lucratively motivated: it was made out of concern that the PGA

would exclude the Colonial from the 1991 Tour,

15

at a time when the South’s most prestigious

14

"TCU Band at All America City Parade," 1965, Fort Worth Star-Telegram Collection, University of Texas at

Arlington Libraries, UTA Libraries Digital Gallery. Accessed July 14, 2023.

https://library.uta.edu/digitalgallery/img/10018643

15

United Press International Archives, “Prestigious Country Club Admits First Black Members,” April 27, 1991.

https://www.upi.com/Archives/1991/04/27/Prestigious-country-club-admits-first-black-members/6456672724800/.

8

and exclusive golf clubs were rather recalcitrant holdouts in admitting members of color

(and women).

16

The Fort Worth neighborhood known as Little Mexico is another example of the

municipal effort to enforce and perpetuate patterns of racial hierarchy and segregation through

urban planning. In 1935, TCU history professor and City Councilman W. J. Hammond

(Progressive Democratic Party) voiced his concern over civic issues such as public housing and

the growth of slums in Fort Worth. He commissioned his fellow professor Austin Porterfield,

who specialized in the scientific sociology of crime and family relations, to evaluate city

neighborhoods.

17

Two years later, after Hammond had been appointed mayor, Porterfield and his

team of TCU graduate student researchers determined that Little Mexico had a high index of

disorganization, amoral behavior, and intellectual deficiency. Their reports illustrated the

common fear of physical proximity and miscegenation with Mexicans, who were considered a

racial group despite their official classification as whites.

18

As a result of Porterfield’s study, the

City of Fort Worth and the local Housing Association proceeded to displace Little Mexico

residents, and the neighborhood was dismantled, as the white-targeted Ripley Arnold Housing

Project took shape in the late 1930’s.

19

Supporters of this project, who documented the Mexican

16

Augusta National did not admit Blacks until 1990 and women until 2012.

17

Peter Martinez, “Colonia Mexicana: Mexican Subjects to Modern Empire in Fort Worth Texas,” Journal of South

Texas, 2019, 13.

Porterfield would then become an official research consultant for Fort Worth Federal Housing Authority in 1939

(Leonard D. Cain. A Man's Grasp Should Exceed His Reach: A Biography of Sociologist Austin Larimore

Porterfield. United Kingdom: University Press of America, 2005).

18

Floyd Armand Leggett, "Social Antecedents and Consequences of Slum Clearance in Fort Worth, Texas,"

Master’s Thesis, Texas Christian University, 1940; Robert Eugene Baker, "Areas of Social Disorganization and

Personal Demoralization in Fort Worth, Texas," Master’s Thesis, Texas Christian University, 1938. Leggett and

Baker, among others, were graduate students at TCU’s Sociology Department, working under the direction of

Professor Porterfield. Note that Leggett’s report also recommended the eradication of Chambers Hill, a Black

neighborhood adjacent to I.M. Terrell High School, because of its abundant moral and social pathologies.

19

In 1939, the Fort Worth Housing Authority also created a separate housing complex for Black Residents called

Butler Place. While the location of the complex was chosen for its proximity to I.M. Terrell High School, it has

since been enclosed by three major highways. Ripley Arnold was later demolished and became the site of

RadioShack Headquarters and later the Tarrant County College Trinity River Campus. Lili Zheng, NBCDFW “Fort

9

families’ incomes in great detail, denied all racist motivations: “the Mexican problem, relative to

housing, is not a matter of racial prejudice or discrimination but purely an economic

circumstance which will make difficult their participation.”

20

History professor Peter Martinez, a

founding member of the Historians of Latino Americans (HOLA) of Tarrant County,

21

identified

an exhaustive list of flaws in this study. Yet the Housing Association’s readiness to accept and

implement its findings is an example of the prevailing views on racial determinism that classified

Mexicans as immoral health hazards. It also exemplifies how members of the TCU community

could use their academic authority to widen the gap in the city’s racial proxemics.

Worth’s Butler Place Redevelopment Plan Moving Forward,” August 31, 2022, accessed July 24, 2023.

https://www.nbcdfw.com/news/local/fort-worths-butler-place-redevelopment-plan-moving-forward/3061620/

20

Leggett, “Social Antecedents,” 92.

21

The Historians of Latino Americans (HOLA) of Tarrant County is an organization of historians, educators,

journalists, activists, librarians, archivists, and active community members who critically examine and document the

racial and ethnic experience of the Hispanic community in the Fort Worth area.

10

The Supreme Court’s 1954 decision to desegregate schools did not yield overnight results

in Fort Worth public schools. White resistance to desegregation persisted, prompting two Black

families to file a lawsuit against the district in 1959.

22

As a result of a Federal Court order, Fort

Worth ISD began desegregation in 1963, when the School Board implemented a “stair-step” plan

22

Tina Nicole Cannon, “Cowtown and the Colorline: Desegregating Fort Worth’s Public Schools,” Ph.D. diss.

Texas Christian University, 2009, 108-109.

11

that integrated one grade per year.

23

The district remained under Federal government oversight

until 1994.

24

Racial attitudes in the TCU and Fort Worth white community were complex. For

example, Randolph Clark, who co-founded TCU as a white-only establishment and remained

involved in TCU affairs until his passing in 1935, was an active member of the Texas

Commission on Interracial Cooperation (TCIC). His son Joseph Lynn Clark, a TCU alumnus,

was the TCIC co-founder and vice-chairman in the 1940’s, later serving as chairman as well. He

was also involved in the National Scholarship Service and Fund for Negro Students. His brother

Randolph Lee Clark promoted middle school education for African American children. He also

fought for the integration of Hispanophone school age children by promoting bilingual education

in public schools.

25

It thus appears that the barriers to integration were not a mere matter of

racist rhetoric or an objection to Blacks being educated. The barriers resided in cultural

misunderstandings, in the fear of physical proximity, and ultimately in the fear of miscegenation.

Nevertheless, Fort Worth residents with ties to TCU, such as TCU Religion Professor Paul

Wassenich, fought for desegregation in Fort Worth, influencing his son Mark Wassenich

(Class of 1964) to do the same at TCU.

23

The school district's desegregation plan was approved by the court, but it had to remain under court supervision

until the plan was complete. The board would declare the plan "complete" in 1967, but the NAACP, with the help of

future Supreme Court decisions, notably Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenberg, would successfully argue in court that

the district remained segregated, forcing the district to draft a series of new plans, which necessitated them

remaining under court supervision.

24

Suzanne Sprague, KERA, “Integration Still a Challenge in Fort Worth,” September 7, 2001.

https://www.keranews.org/archive/2001-09-07/integration-still-a-challenge-in-fort-worth

25

Brian Hart, “Clark, Randolph Lee,” Handbook of Texas Online, accessed July 14, 2023,

https://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/entries/clark-randolph-lee

12

Global Context: WWII and the Cold War

When the U.S. became fully engaged in the Second World War in 1941, our country had

greater needs for workers and workforce development; among this development, significant

investment was made in the training and recruitment of Black men in Texas and in Fort Worth.

For example, white instructors such as L. C. McRorey would provide training at the Negro War

Industries Training School, a Fort Worth campus of the National Defense School. In the

following illustration, McRorey is shown demonstrating to the class the method of shaping iron.

As opposed to the mention of McRorey’s name, the African-American man who looks on

remains unnamed.

26

Figure 5: "“L. C. McRorey, instructor in blacksmith shop of the Negro War Industries Training School, National Defense School.

McRorey is shown demonstrating to the class the method of shaping iron." Fort Worth Star-Telegram, 1942.

26

“Negro War Industries Training School,” 1942, Fort Worth Star-Telegram Collection, University of Texas at

Arlington Libraries. https://library.uta.edu/digitalgallery/img/20056020

13

The “last good war” also brought groups from Europe and Eastern Asia, who sought

refuge in America. Their arrival would be visible in higher education, too. For instance, Texas

Wesleyan University welcomed two Japanese students from relocation camps in 1941 with War

Department approval. In the wake of World War II, a struggle for supremacy between the U.S.

and its allies and the Soviet Union and its satellites resulted in fierce competition and ideological

war. Both sides claimed to serve the people. Racially segregated TCU was not immune to

communist criticism regarding the unequal treatment of Black people. In 1963, Chancellor

Moudy cautioned the TCU community against racist practices on campus that might give

credence to communist arguments:

27

In the 1940s, decolonization was also in full bloom as former European colonies were

advocating for political independence in Asia, Africa, the Caribbean, and Latin America. Even

though the U.S. supported several pro-independence leaders, to a great extent in order to rally

them against the communist bloc, student activists (at home and abroad) pointed the finger back

to America, highlighting its ill treatment and oppression of U.S. populations of color. At the

national level, a groundswell of civil rights activity also began after World War II, and TCU

moved slowly with the nation. Conflicts such as the Korean War and the Vietnam War opened

the eyes of young TCU students to parts of the world and ethnic identities that, for them,

27

Statement by Moudy, June 7, 1963a.

14

were largely underexplored, leading some to question the validity of international and

racial privilege.

28

Context: Integration in North Texas universities

In 1954, the Supreme Court ruled in Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas that

all public schools, and by extension all public facilities, must desegregate. The majority ruling

clarified, however, that the desegregation could occur with “all deliberate speed.” In some

locations, “deliberate speed” took two decades. Texas’s reluctance to desegregate its public

universities meant that private establishments experienced little pressure to integrate at all.

29

Most universities followed a common pattern to desegregation. They first admitted Black

graduate students, then Black undergraduates in special programs such as evening courses that

did not lead to the full experience of student life. For private universities, desegregation of the

main undergraduate campuses would take place on average ten to twelve years after that of the

graduate schools. Among public universities in the state of Texas, UNT was the first to allow

African American enrollment at its graduate and main campuses, between 1950 and 1956.

Private North Texan universities followed in the early 1960’s, SMU being the first and Rice

University being the last. Nevertheless, the RRI could not retrieve the exact dates of each

desegregation step for all higher education establishments, because several schools (e.g., Texas

Wesleyan) did not maintain public records of Black enrollment and instead elected to

desegregate quietly and discreetly.

28

Charles Ess, The Skiff, “Packaged People,” November 21, 1969.

https://repository.tcu.edu/handle/116099117/15289

29

Runyon v. McCrary, the landmark case by the U.S. Supreme Court which outlawed racial discrimination and

segregation in private schools occurred in 1976.

15

At Southern Methodist University, African American ministers sporadically attended

classes at Perkins School of Theology as early as 1946. However, SMU officially changed its

bylaws in 1950 to allow the Perkins School to admit African Americans. African Americans

began attending classes at Perkins in January 1951. Their enrollment was restricted to attendance

in classes; no African American students were permitted the full experience of student life, such

as dining or living on campus. The first three students did not maintain acceptable academic

standing and were dismissed. In the fall of 1951, five Black students enrolled.

30

SMU admitted

African American students to evening classes in the law school in the fall of 1955. Nevertheless,

none of them graduated until 1964, two years after the first Black undergraduate student was

admitted on SMU’s main campus.

31

Athletics would also remain white only, until Jerry

LeVias was offered a football scholarship in 1965, breaking the race barrier in the

Southwest Conference.

UNT desegregated its graduate school in 1950. Black undergraduates started to enroll in

February 1956, including football athletes, a notable distinction as this occurred ten years before

the SWC, and Abner Haynes became the first Black athlete to integrate college football in a four-

year institution in Texas. Nevertheless, public facilities on the Denton campus remained

segregated until 1963. In Austin, the University of Texas opened its doors to African American

undergraduates in 1956 as well, and other schools followed.

32

By 1958, SMU, TCU, and Baylor

had desegregated their graduate schools.

33

30

Merrimon Cunninggim, Perkins Led the Way: The Story of Desegregation at Southern Methodist University,

(Dallas: Perkins School of Theology, Southern Methodist University, 1994).

31

Scott A. Cashion, "And So We Moved Quietly": Southern Methodist University and Desegregation, 1950-1970,"

Ph.D. diss., University of Arkansas, 2013.

32

Dwonna Goldstone, Integrating the 40 Acres: The Fifty-Year Struggle for Racial Equality at the University of

Texas (Greece: University of Georgia Press, 2012).

33

Richard Morehead, Dallas Morning News, “College Students Favor Gradual Integration,” December 12, 1958, 4;

Morehead, Dallas Morning News, “35 Schools Lower Ban,” March 23, 1958; Morehead, Dallas Morning News,

16

At Baylor University, the governing board voted to desegregate 1963; the first

undergraduate African American students enrolled in January 1964. When TCU officially

desegregated its main campus in 1964, Rice University was the only Texan university in the

Southwest Conference that remained segregated. Nevertheless, Texas Wesleyan University’s

first Black undergraduate, Beatrice Hurst Cooksy, was a transfer student who enrolled in 1965.

She attended only one year, as she graduated with a B.S. in Elementary Education in 1966. Her

photo was not in the annual. The university’s student newspaper, the Rambler, and the yearbook,

TXWECO, did not mention integration.

“Quietly” was the golden rule for higher education desegregation in North Texas, and

TCU was no exception. Despite a small and silent presence of people of color since the early

1900, the early 1950’s marked a transition in the university’s racial landscape. In 1951, President

Sadler addressed the Board of Trustees and acknowledged the enrollment and physical presence

of African Americans in TCU programs.

34

In Sadler’s report (which was summarized in The Skiff

as illustrated below), TCU’s chief executive officer sought to reassure the campus community

that TCU retained its segregationist policy in barring African Americans from enrolling. The few

exceptions (two or three Black soldiers, a group of African American public school teachers

seeking advanced degrees, and one Jarvis Christian College student taking TCU classes) were

carefully planned to take place out of sight and outside of the main campus classrooms: in the

evening, off-campus, and via individual conferences.

“Three Dallas Institutions Accepting Few Negroes,” January 7, 1959; Morehead, Dallas Morning News, “Integration

Now the Rule in Most Colleges,” July 7, 1960.

34

M. E. Sadler, Chancellor’s Report to the Board of Trustees, 9. Records of M.E. Sadler, Box 2, Folder “Reports to

BOT 1963-64,” Special Collections/TCU Archives, Fort Worth, TX.

17

35

Early silent presence of racial and ethnic minorities

When TCU dropped its racial barriers in 1964, the presence of students of color was

nothing new. University publications, such as the student newspaper The Skiff and The Horned

Frog yearbook, featured several illustrations of the enrollment, academic employment, and

active participation of racial and ethnic minorities. Nevertheless, their otherness was mollified by

their international status. As early as 1902, for example, Abdullah Ben Kori was admitted to

TCU as a student. Born in Tripoli in the Syrian province of the Ottoman Empire (present day

Lebanon), Kori attended schools in Beirut and Rome before moving to the United States in 1900.

He graduated with a Bachelor of Arts in 1904, and then remained to pursue a Master’s degree,

during which time he also served as a professor of Modern Languages. Upon completion of his

graduate degree, Ben Kori was promoted to Department Head, likely the first student and first

faculty member of color at TCU. Kori spoke and taught German, French, Spanish, Italian,

Modern Greek and Arabic.

36

35

The Skiff, "Negroes Attending TCU, Sadler Says," November 2, 1951, accessed June 14, 2023.

https://repository.tcu.edu/handle/116099117/14454

36

Texas Christian University Bulletin, Pictorial Presentation of Texas Christian University with Biographical

Sketches of its Faculty, 1903. https://repository.tcu.edu/handle/116099117/42190

18

Figure 6: Abdullah Ben Kori, 1905

37

While the yearbooks note that Ben Kori hailed from Tripoli, few TCU documents discuss his

race or specific ethnicity, possibly because his Middle Eastern origins and Arab ethnicity were

interpreted as white. Only Colby Hall would describe him as “a temperamental Turk of fine

character and loyal devotion.”

38

In 1906, he relocated to Forest Grove, Oregon and changed his

name to Alexis Ben Kori, occasionally using “Abdullah” as his middle name. Other photographs,

such as that of Mrs. Vida Cantrell, class of 1915, have prompted speculation about the possible

presence of students of color “passing” as white or silencing their ethnicity during the

university’s first decades.

39

37

The Horned Frog, TCU Yearbook, 1905, 27. https://repository.tcu.edu/handle/116099117/11032

38

Colby D. Hall, History of Texas Christian University: A College of the Cattle Frontier, (Fort Worth: Texa

Christian University Press, 1947), 123.

39

Frederick W. Gooding, Jr, Sylviane Ngandu-Kalenga Greensword, and Marcellis Perkins. A History to

Remember: TCU in Purple, White, and Black (Fort Worth, Texas: TCU Press, 2023), 51-52.

19

40

Figure 7: Mrs. Vida Cantrell, Class of 1915, was a non-traditional student, not only due to her married status. She is recorded to

have attended only one year, which would have made her attendance as a possible student of color more discreet. Nevertheless,

she was an active member of four student organizations, including Yearbook staff.

Integration in the student body

The 1940’s

The first overt examples of Indigenous and Asian students on TCU’s campus can be

traced to the early 1940’s. While white students, such as J. C. Oneal and brothers Van “Hoss”

Hall and Johnnie Hall, were given the epithets “Chief from the Indian country” and “The Indian”

solely due to their outstanding football performances,

41

The Horned Frog and The Skiff indicate

that Jack Jordan, a registered Cherokee, attended TCU in 1941.

42

Likewise, the enrollment of

40

The Horned Frog, TCU Yearbook, 1915, 30. https://repository.tcu.edu/handle/116099117/11041

41

The Horned Frog, TCU Yearbook, 1943, 77. https://repository.tcu.edu/handle/116099117/11069; National

Archives at St. Louis; St. Louis, Missouri; WWII Draft Registration Cards For Texas, 10/16/1940-03/31/1947;

Record Group: Records of the Selective Service System, 147; Box: 1121; The Skiff, “N. T. A. C. Game

Heads Chores For '44 Squad,” September 20, 1940, vol. 38, no.1.

https://repository.tcu.edu/handle/116099117/13534; Year: 1930; Census Place: Precinct 1, Kaufman, Texas;

Page: 20A; Enumeration District: 0002; FHL microfilm: 2342100.

42

The Horned Frog, TCU Yearbook, 1941. 287; The Skiff, “SA Fact,” March 21, 1941, vol. 38, no. 26.

https://repository.tcu.edu/handle/116099117/13558

20

Tommy Moy, an Asian American student from New York, did not appear to trigger much

resistance. Moy was an actively engaged student, involved with the TCU fencing team as an

athlete, then as a coach; he was also on the yearbook staff and a member of the Meliorist Club,

just to name a few. Upon completion of his bachelor’s degree, he remained at TCU to pursue a

graduate degree.

The presence of Indigenous and Asian racial identities in the 1940’s did not seem to

trigger the same resistance by the TCU community as that of Black students. In the midst of

World War II, the university obtained government contracts to teach military officers and pilots.

A handful of Black officers enrolled in evening classes in 1942, which were taught by TCU

faculty members. While the coursework fell under the umbrella of the Evening College, classes

were held off-campus and did not lead to a TCU degree.

As the Evening College program continued for at least a decade, President Sadler sought

to reassure a disgruntled parent and alumna in 1952: “In the sense in which you are evidently

thinking of it, we do not have Negroes enrolled in Texas Christian University.”

43

He went on to

43

M. E. Sadler, “Letter to Mrs. Betty Wilke Pederson,” 1952, box 10, Archives and Special Collections, Records of

M. E. Sadler, Mary Couts Burnett Library / RU 14.

21

explain that TCU educated Black soldiers exclusively -- and only to comply with a request from

military authorities:

As detailed in the historical context section, discrimination against Tejanos also

abounded in Fort Worth, even as the university welcomed students from Latin America. Elba

Altamirano (born of a British mother and Mexican father), for example, was recruited from

Mexico City; she earned a scholarship to pursue graduate studies at TCU in 1944.

44

44

“Elba Altamirano of Mexico City, Mexico, Student at Texas Christian University (TCU),” Nov 14, 1944.

University of Texas at Arlington Libraries, Special Collections. https://library.uta.edu/digitalgallery/img/20038830.

22

The trend continued after the war ended. Students of color were welcome, as long as they were

not U.S. citizens: Inn Wai Lau from Hawaii, Efrain Perez-Ortega from Puerto Rico, or Manuel

Paez from Colombia. The first identified Chicano to graduate from TCU was Victor Vasquez,

class of 1965. Sub-Saharan African students, however, were not admitted, as they fell into the

racial category of “Negroes,” as exemplified by the 1961 failed attempt to provide TCU

scholarships for Congolese students.

45

Figure 8: Inn Wai Lau, 1948

45

The Horned Frog, TCU Yearbook, 1948, 123.

23

46

Figure 9:Efrain Perez-Ortegar, 1948

.

47

Figure 10: Manuel Paez, 1948

46

The Horned Frog, TCU Yearbook, 1949, 115.

47

The Horned Frog, TCU Yearbook, 1950, 54.

24

25

Figure 11: In 1961, Chancellor Sadler denied Christian ethics professor Harold L. Lunger's request for TCU to participate in a

program that would admit Congolese students, because of their Black racial status.

26

The Native Americans gained increasing visibility following World War II. Articles and

captions in the Skiff and The Horned Frog detailed the tribal affiliations of several students,

starting in the 1950s. Otis Albert Penn, an Osage Indian from Pawhuska, Oklahoma, attended

TCU in 1948.

48

Other indigenous students would follow. In 1952, Claire Taylor, Maxine Linn,

and Donna Gay Knox, three high school graduates from Arizona, joined the Horned Frogs. Linn

would explain that she came to TCU because of its nursing program: “We have a hospital on the

Indian reservation where I live, but they don’t have a nursing school.”

49

In 1953, Joyce Hammett

enrolled as a twenty-one-year-old transfer from Oklahoma A&M. A radio major, she would soon

become KTCU’s station manager. This great granddaughter of survivors of the Cherokee forced

migration known as the “Trail of Tears” was also the sister of the Chief of the Cherokee tribe

in Oklahoma.

50

48

The Skiff, “Names ’n Notes,” June 18, 1948, vol. 46, no. 36.

49

The Skiff, “Rattlesnake Eggs and Nursing Interest Three Arizona Coeds,” October 31, 1952, vol. 51, no. 7.

50

The Skiff, “Cherokee Lassie Ah-Neu-Et Finds Happy Stomping Ground at KTCU,” November 13, 1953, vol. 52,

no. 9.

27

Figure 12: Celebratory coverage of Hammett's new role, November 13, 1953

28

For African Americans, the first cracks in segregation at TCU emerged in the 1950s, but

they were neither subtle nor celebratory. Rumors started to circulate in the media, to the great

dissatisfaction of TCU’s leadership, who reprimanded staff in the marketing and

communications department.

51

The mere possibility of Black integration generated ire on the part

of several members of the main campus community, as illustrated by the written complaint of

one TCU alum.

52

51

“Memo to President M.E. Sadler, 05/23/1952.” TCU Special Collections. Records of M.E. Sadler. Record Unit

14. Box 10; “Memo to Dr. M.E. Sadler, 08/05/1952,” TCU Special Collections. Records of M.E. Sadler. Record

Unit 14. Box 10.

52

Letter reads: “Gentlemen: I’m very sorry this has had to happen, but I’m giving you the reason you won’t receive

numerous contributions! To quite a large amount of “exes” there is no reason whatsoever for negroes to attend

T.C.U. as long as they have schools that can offer the same courses. I assure you (along with quite a few of my

friends who are also “exes”) that I will never contribute to anything our ex-school needs and will never let my

children attend a school with negroes! I might add that we are all terribly sorry this has had to happen.”

29

The Supreme Court decision Sweatt v. Painter (1950) required that universities admit all

qualified students to their graduate programs, and in 1951, the TCU School of Education began

offering evening courses to African American teachers. The courses were segregated, however,

and offered off campus at Gay Street Elementary School. This program was designed for Black

teachers seeking college credits to fulfill new certification requirements. However, two program

participants who had enrolled in 1951, Gay Street Elementary Principal Lottie Mae Hamilton and

Fort Worth teacher Bertice Bates, had earned enough credits to earn a Master’s degree. TCU

initially refused to grant degrees to these Black students. After years of deliberation, the two

educators obtained their diplomas but were not allowed to attend the still-segregated

commencement and graduation ceremonies in 1956 (Hamilton) and 1960 (Bates). Prof. Sandy A.

Wall, who taught classes within this program, explained that the courses were discontinued in

1956, but when the TCU School of Education desegregated in 1962, numerous program

participants enrolled at TCU to pursue Master’s degrees, following the example of Mrs.

Hamilton and Mrs. Bates. Among the first to graduate on campus were Mrs. Juanita Cash and

Mrs. Reva Bell, who were granted their diplomas in 1965.

53

The Brite College of the Bible (which had a separate Board of Trustees but was located

on the TCU campus) agreed to integrate its graduate programs in 1950,

54

observing that the

obligation to “train youth for a life service in Christ's Kingdom […] overrode any contention that

we are in our rights to refuse Negroes on the basis that we are a private school.”

55

They were

Betty Wilke Pederson, “Letter to the Student Office,” box 10, Records of M. E. Sadler, Archives and Special

Collections, Mary Couts Burnett Library / RU 14.

53

The Skiff, “Teacher Relates Blacks’ Rise,” February 15, 1977, vol. 75, no. 69.

54

Brite only offers graduate programs.

55

Citation.

30

possibly following the lead of their disciplinary peers at the Perkins Seminary at SMU, where the

first Black students enrolled in 1951. The first African American student at Brite, James Lee

Claiborne, enrolled in 1952 and graduated in 1955. Daniel Godspeed and Vada Phillips Felder

would soon join him. The three graduate students, all married and living off campus, were not

allowed to eat on campus, and Brite set up separate food service for them in Weatherly Hall, a

set up similar to the Seminary at SMU. In 1959, Brite alumna Vada Felder invited Dr. Martin

Luther King, Jr., to Fort Worth to speak at Brite. Despite its independent status, Brite’s physical

location required TCU approval for such events. The university refused permission for King to

speak on campus, and the event instead occurred at the newly desegregated Majestic Theater. Dr.

Harold Lunger, professor of Social Ethics at Brite, hosted a reception at his home for Dr. King

and other Brite faculty members.

Despite Brite’s modest efforts to admit a handful Black students in the 1950s, TCU’s

undergraduate programs were in no hurry to desegregate, even with the need for a qualified and

educated Black workforce in Fort Worth. In 1962, a dire shortage of Black nurses in Black

hospitals led Harris School of Nursing, which had its own board of directors, to pass a resolution

stating that it would admit students to its nursing program “without regard to race, color, or

creed.”

56

Their first students enrolled in 1962. This group included the trailblazing Allene Jones,

who, like the Black Brite students, was married and older than typical undergraduate students.

Even as African American students began to enroll at SMU and Arlington State College

(now, University of Texas-Arlington) in 1961 and Baylor in 1963, the TCU Board of Trustees

dragged its feet. In 1962, faculty members at Brite and the Harris College of Nursing had begun

to exert pressure on the Board for integration of the whole TCU campus to support the Black

56

TCU News Service, “Press Release,” 1964, Special Collections, TCU Mary Couts Burnett Library.

https://repository.tcu.edu/handle/116099117/21233.

31

students who were in their colleges: Harris needed TCU to offer lower-level classes for Black

students before they took their nursing training, and Brite wanted their students to be able to

enroll in undergraduate classes along with the general student population.

In June 1963, Provost and Vice Chancellor for Academic Affairs James Moudy issued a

statement to the Board of Trustees that no TCU department should exclude African Americans

from admission.

57

Although this statement was certainly instrumental in orchestrating

desegregation, Moudy’s six-point rationale was not without controversy at the time. First, he

noted that the presence of international students of color on campus, including some of darker

complexions, contradicted the university’s systematic refusal of students of African descent.

Secondly, he highlighted the mental and intellectual equality among races, dispelling any belief

in Black people’s inability to learn and benefit from a TCU education. Moudy reminded the

Board that since the most prestigious universities that TCU sought to emulate had desegregated

campuses, desegregation was a key strategy for institutional effectiveness. Additionally, the

Christian principle of racial equality should, according to the vice chancellor, serve as a moral

compass to consider each applicant according to their human worth instead of their race. Moudy

paired this tension with the American principle of human equality, especially in a Cold War

climate. Indeed, his concern was that refusing Black enrollment might give proponents of

communism room to argue that the American education system was morally corrupt by racism

and bigotry. Finally, he attempted to reassure parents by addressing what he perceived to be the

greatest objection to desegregation: interracial courtship. Moudy encouraged white parents to

trust that their children’s rearing and natural instincts would be unlikely to lead to interracial

marriage or miscegenation among students, and therefore parents should not feel threatened to

57

James M. Moudy, “Photocopy of Statement by Moudy on Race,” 1963. Special Collections, TCU Mary Couts

Burnett Library. https://repository.tcu.edu/handle/116099117/21231.

32

have their children share physical space with students of color.

58

Moudy’s comments addressed

fears in Texas that dated back to the birth of the Texas Republic, when the first anti-

miscegenation laws were passed in 1837.

59

Texas refused to repeal its anti-miscegenation laws

until 1970, three years after the Supreme Court decision in Loving v. Virginia (1967), which

invalidated such laws.

60

Additionally, in the era of desegregation, fears of miscegenation played

a key role in the ideology that prompted intense resistance to the Civil Rights Movement in

Fort Worth.

61

Figure 13: "Photocopy of statement by Moudy on Race" pg. 3

58

Brite professor of ethics Harold Lunger advocated for TCU’s participation in a national scholarship program that

would welcome international Congolese students during the post-independence crisis in the Great Lakes region.

Sadler replied, in a handwritten note: “Cannot participate unless and until T.C.U. Trustees vote to admit negroes.”

Records of M.E. Sadler. R/U 14, box 10, TCU Special Collections.

59

Charles F. Robinson II, “Legislated Love in the Lone Star State: Texas and Miscegenation,” The Southwest

Historical Quarterly, July 2004, vol. 108, no. 1, 67.

60

Martha Menchaca, “The Anti-Miscegenation History of the American Southwest, 1837-1970,” Cultural

Dynamics, vol. 20, no. 3, 2008, 311.

61

Gandy, “Trouble Up the Road,” 60.

33

In the same manner as Moudy did, TCU’s Student Government Association, led by

senior undergraduate Mark Wassenich, petitioned the Board of Trustees in November 1963 to

drop racial barriers.

62

After much discussion, on January 29, 1964, the Board moved to integrate

TCU, the seventh of eight Southwest Conference schools to do so. Only Rice, whose founder

expressly forbade desegregation in the university charter,

63

was later than TCU to integrate. TCU

President M. E. Sadler wrote, “In my own personal judgment, in the judgment of the faculty, and

in the judgment of our student leaders, we believe that the time has come for the Board of

Trustees of Texas Christian University to take action which will remove the one racial bar which

remains at TCU.” And so the structural bar came down.

And yet, within the same declaration, the Trustees sought to reassure white stakeholders

that TCU would largely remain a white campus:

We will never have very many negro students enrolled. This is due to two or three

basic factors. Our admissions requirements and course requirements are being

raised increasingly, and very few negro students could qualify for admission. Our

tuition and fees will be raised from time to time, and relatively few negro people

would have the funds necessary to finance the kind of education we offer here.

The third factor grows in part out of my experience as a Trustee of a negro college

and a negro university. No matter how much integration previously white colleges

and universities might allow, almost all negro college students will want to attend

their own institutions of higher learning.

64

The minutes of that day’s meeting detailed a $5 raise in tuition per semester hour. By March of

that same year, TCU would approve a five-year formal affiliation between TCU and its sister

institution, the historically Black Jarvis Christian College, which was established in 1912 by

62

Mark Wassenich, Interview with Mark Wassenich, by Sylviane Greensword, Race and Reconciliation Initiative

Oral History Project, Texas Christian University, 2021. https://repository.tcu.edu/handle/116099117/52346.

63

Brittany Britto, The Houston Chronicle, “Rice’s Reckoning: University to Launch Task Force to Address its

Segregationist History,” June 14, 2019. https://www.houstonchronicle.com/news/houston-

texas/education/article/Rice-s-reckoning-University-to-launch-task-14061581.php#

64

Photocopy of TCU Board of Trustees Minutes. 1964. Special Collections. TCU Mary Couts Burnett Library.

https://repository.tcu.edu/handle/116099117/21232.

34

TCU founders and board members. TCU became financially and academically responsible for

Jarvis, setting the curriculum and hiring the faculty as well. Thus, segregation by race still ruled

the South, Texas, Fort Worth — and TCU. “Separate but equal” was the law of the state. The

Disciples of Christ, which was affiliated with TCU, had greater governing authority over the

Black denominational college in Hawkins, 125 miles from Fort Worth, in East Texas, to help

keep in place that distinction between Black and white students. Nevertheless, while the Black

student population remained relatively dismal at TCU, the mostly white student population

would drop by 24% after desegregation.

65

66

As the background section above reminds, desegregation did not mean integration, and

the first years of TCU desegregation were difficult for the pioneering students, staff, and faculty

members of color who came to TCU in these years. In the fall of 1964, five Black high school

graduates were admitted but did not return the following year. According to Marian Brooks

Bryant, who was among these five students, the climate was so unwelcoming that they elected to

leave TCU and enroll in other universities and colleges.

67

The Race and Reconciliation Initiative

65

M.E. Sadler, The Chancellor’s Report, Texas Christian University, 1965-1973, Pgs. 10-13, Records of James E.

Moudy, R/U 16, accession 2017-009. box 2, TCU Special Collections.

66

The Skiff. “Students Rejecting Plan.” November 22, 1963, Vol. 61, No. 19

67

Marian Brooks Bryant, Interview with Marian Brooks Bryant, by Sylviane Greensword, Race and Reconciliation

Initiative Oral History Project, Texas Christian University, 2021.

https://repository.tcu.edu/handle/116099117/52346.

35

has only been able to name and locate two of these students. This erasure was surely strategic, as

President Sadler feared that publicizing the number of African American undergraduates might

generate negative publicity, as he detailed in a letter to the Registrar. This decision to keep

demographic information confidential was modeled on other recently integrated universities, to

which the President referred for counsel. He thus concluded, “If we want to keep a little private

record [of the number of Black students who enrolled at TCU] for our own selves, that might be

all right.”

68

Assistant Chancellor Melton disagreed, as he believed this was a matter of public

knowledge, despite a similar desire to keep details under wraps: “I sincerely hope that when

registration is over, we can make a short, accurate statement that will make a one-day story –

then be forgotten,” he wrote back.

69

While TCU omitted the names of these students in their

public record, the local Fort Worth Black community knew of and remembered the story of

Marian Brooks Bryant; his brother would become the Tarrant County Commissioner of TCU’s

district, and his future sister-in-law would become TCU’s first Black Homecoming Queen. In

1965, a year after TCU’s first Black undergraduates enrolled and then transferred to other

campuses, fourteen Black students were admitted. Because their predecessors had warned them

of the hardship ahead, these fourteen students decided to remain united, to support one another,

and to commit to graduating on time. They would graduate with the class of 1969, the first fully

integrated class.

68

M.E. Sadler, “Letter to Mr. Calvin Cumbie, Registrar.” January 28, 1964, Records of M.E. Sadler, Record Unit

14. Box 10, TCU Special Collections.

69

Amos Melton, “Letter to Dr. M.E. Sadler.” January 29, 1964. Records of M.E. Sadler. Record Unit 14. Box 10,

TCU Special Collections.

36

Student voices

Integration was experienced differently among students, depending on a student’s race,

ethnicity, and other factors. Despite the university’s standard practice of treating desegregation

“quietly” in its advertising and media coverage, students were well aware of the changes that

were occurring, and most had strong opinions about what was happening on campus..

70

Although

student opinions were the result of personal experiences, they were deeply informed by academic

knowledge of national and world events. In other words, the education they received at TCU and

through news outlets available on campus guided their perspectives more than their personal

feelings did. Just as TCU’s administration demonstrated apprehension and disapproval of

interracial countship, so too did TCU’s student body. The pioneering Black students who

ushered in desegregation were shaped by a number of common experiences. For example, while

macroaggressions against students of color were few, microaggressions were not. The students of

color who persisted did so because they were focused on the end result (getting a degree), not the

student experience.

Curriculum, faculty and staff

As a liberal arts university, TCU provided coursework that reflected some of the diversity

of world cultures. This diversity did not, however, cover racial groups, such as Black and AAPI

identities. In this regard, TCU aligned with most of its contemporary universities in the U.S.

Sociology, anthropology, modern languages, history, geography, and the art departments

offered classes on the Americas and Europe. In 1940, the only class that discussed Asian and

70

This summary is based on a survey of contemporaneous campus publications, oral histories collected through the

Race and Reconciliation Initiative Oral History Project, Civil Rights in Black and Brown, and other academic

projects such as Professor Dan Williams’s Honors Special Project: Vision and Leadership course.

37

African civilizations did so exclusively in the context of their subaltern relations with the

British metropole:

71

Figure 14: Catalog description for the upper-level course History 139

With the exception of the graduate course offerings documented in this report’s Historical

Context section, TCU’s curriculum remained uninterested in U.S. racial minorities until 1945,

when the department of sociology started offering a course that grouped ethnic subcultures and

other marginalized groups. The “American Minority Groups” class was an ambitious attempt to

study all these minorities in one semester. If the focus on minority “problems” was typical of its

era, it was also limiting, given that this problem-oriented approach was the only opportunity for

students to learn about non-white identities.

72

Figure 15: Catalog description for the upper-level course Sociology 334

TCU course offerings provided greater attention to American Indigenous history,

geography, and cultures. For example, in the 1930’s and 1940’s, Dr. Hammond taught pre-

71

Texas Christian University Catalog, 1940. https://repository.tcu.edu/handle/116099117/48397.

72

Texas Christian University Catalog, 1945. https://repository.tcu.edu/handle/116099117/48409.

38

history of the Western hemisphere, American Indian civilization and culture, as well as colonial

contact between Natives and Europeans. In the next two decades, Dr. Martine Emert, an

associate professor of geography who had lived among the Navajo and Pueblo Natives, would

lecture and curate exhibits on Southwest Indian handicraft.

73

Likewise, the departments of Art,

History, Sociology and Anthropology offered Indigenous-related coursework and sponsored

scholarly research.

74

However, the scope of these classes was largely limited to a white

perspective, and all their instructors were Caucasians. The Skiff advertised exhibitions and

publications resulting from the coursework and research but did not mention interventions,

classroom visits, or lectures by Indigenous people. Not until 1974, with the arrival of Mrs. Gail

Pete, a part-Choctaw, part-Cherokee who specialized in Indian art, did this curriculum get

delivered by a faculty member who understood the subject through an experiential lens.

75

As previously mentioned, TCU sociologists tended to study Chicano culture through the

lens of social ills. While the History department offered courses on Mexican history, they did not

offer coursework on the history of Mexican Americans, despite its broader representation in Fort

Worth and in Texas. Nevertheless, some graduate students, such as Arnoldo DeLeon, a Mexican

American alum who started graduate school at TCU in 1970, pursued this research.

76

DeLeon

reported being the only Mexican American in TCU’s doctoral program in history (the few other

Hispanics were Cuban) and was pleased with his rapport with his fellow students and

73

The Skiff, “Dr. Emert to Lecture, Show Indian Handcraft,” November 16, 1951, vol. 50, no. 9; The Skiff, “Dr.

Emert Will Discuss Indian Culture in Class,” November 14, 1952, vol. 51, no. 9.

74

The Skiff, “Hammond in California,” March 12, 1954, vol 51, no. 22; The Skiff, “Many Departments List Courses

for First Time Next Semester,” January 15, 1954, vol. 52, no. 15; The Skiff, “Fine Arts Faculty Displays Abstract,

Realistic in Show,” January 22, 1954, vol. 52, no. 16; The Skiff, “3 History Courses Added,” September 1, 1959,

vol. 57, no. 14; The Skiff, “Dr. Worcester Writes Article On Sioux Chief,” November 20, 1964, vol. 63, no. 19; The

Skiff, “Ancient Cultures Studied,” November 5, 1965, vol. 64, no. 15; The Skiff, “Prof Digs Baja,” May 24, 1966,

vol. 64, no. 56.

75

The Skiff, “Indian Art is Specialty of New Faculty Member,” September 17, 1974, vol. 73, no. 8.

76

DeLeon is a first-generation high-school, college, and graduate school alumnus.

39

professors.

77

Working under Donald E. Wooster, a Latin Americanist, DeLeon wrote a thesis on

great migrations in Mexican American Texas (1910-1920)

78

and a dissertation on Anglo attitudes

towards Mexicans in Texas.

79

Asian and Black contributions to the diversity of world cultures were virtually invisible

in the university’s first hundred years of existence. Academic Affairs considered an Asian

Studies program in 1972, but the motivation was primarily to increase American students’

awareness of China in the context of the Cold War; at the time, universities nationwide were

competing to hire the few experts in this field.

80

TCU did not adopt its minor in Asian Studies

program until the late 1990s.

81

The closest thing to African American studies was initiated in late

1967, almost four years after desegregation. Given the national context of Black studies, which

was just beginning at this time, TCU was relatively ahead of its counterparts. By way of a series

of six public lecture-discussions, the Experimental College invited speakers from TCU and

Jarvis Christian College to lead a noncredit, tuition-free course for students, faculty, and the

community. The Skiff coverage of the series’ launch reads:

The first in the series of six tomorrow night will be telescoped Negro history, not

Black history. Dr. A.L. King, assistant professor of history, says there is a

difference, and he will be the first lecturer in the non-credit, tuition-free ‘Negro in

American Life’ course. He said, ‘Negro history builds pride by showing people

that the Negro has made a definite contribution to American history. […] Students

always learn about Custer’s last stand, but they never hear about the two

regiments of Negro soldiers who fought in the Indian wars.’”

82

77

Arnoldo De Leon, Interview, July 25, 2016, San Angelo, TX , Civil Rights in Black and Brown,

https://crbb.tcu.edu/clips/7028/biographical-information-early-life-and-education, accessed June 22, 2023.

78

Arnoldo De León, "Mexicans and Mexican-Americans in Texas, 1910-1920," Master’s thesis, Texas Christian

University, 1971.

79

Arnoldo De León, "White racial attitudes toward Mexicanos in Texas, 1821-1900," Ph.D. diss., Texas Christian

University, 1974.

80

The Daily Skiff, “Asian Studies Program Mulled; Relevance, Experts Needed,” February 29, 1972, vol 70, no. 79.

https://repository.tcu.edu/handle/116099117/15455

81

The Skiff, “AddRan Looks to Hire Faculty Member to Teach Chinese,” February 22, 2007.

https://repository.tcu.edu/handle/116099117/45869

82

The Skiff, “First Series Talk: Negro not Black,” October 15, 1968, vol. 67, no. 8.

40

This experiment led to the first Black history class in 1969. “From African civilizations to

contemporary era in America” compressed 3,000 years of history on 3 continents into a three-

credit hour, one-semester course.

83

During her 1971 visit to TCU, American journalist and

social-political activist Gloria Steinem publicly denounced the existence of racism and sexism in

the university’s curriculum.

84

Despite these small interventions, Black, Indigenous and students of color could not see

themselves in the TCU curriculum, nor could they recognize themselves in the textbooks

assigned. They did not accept the epithets professors often used in speaking to and about

them.

85

And they did not identify with the faculty, who were until the late 1960s overwhelmingly

white. Eventually, TCU alumna Allene Jones joined the School of Nursing faculty in 1968;

alumna Dr. Reva Bell became the first African American faculty member in the School of

Education in 1974.

86

Until 1983, they would remain the only Black faculty members at TCU.

87

As students of color tried to find a sense of community, they often found caring and

understanding companions among the cafeteria, landscaping, and janitorial staff, who, since the

university’s founding, were Black – then increasingly Brown. However, during the years that

TCU was transitioning to integration, the Race and Reconciliation Initiative identified no

administrative staff of color.

83

TCU Race and Reconciliation Initiatives Committee, First Year Report, April 21, 2021.

https://repository.tcu.edu/handle/116099117/52380

84

TCU Race and Reconciliation Initiatives Committee, First Year Report, April 21, 2021.

https://repository.tcu.edu/handle/116099117/52380

85

For example, Ivory Dansby, who transferred from Jarvis in 1965, reported being called “my favorite colored girl,”

and hearing the word “nigra” as her professor routinely, nonchalantly used this term to refer to her. Dansby also

shared that TCU history professors used textbooks with derogatory, racist content. Wake: The Skiff Magazine, “On

Breaking the Negro Cycle,” May 1968, 9. https://repository.tcu.edu/handle/116099117/21235.

86

First Black Ph.D. to obtain tenure at TCU

87

TCU hired a part-time Upward Bound Black instructor in the early 1970’s, but this instructor left soon after.

41

Athletics

As TCU’s leadership was preparing for desegregation in 1963, Chancellor Sadler charged

his assistant Amos Melton to explore the integration of athletics at fellow SWC institutions.

Although no university had yet permitted a Black player on the field, track, or court, Baylor and

UT anticipated a change in this trend within the year. TCU proceeded with caution by observing

how these universities would process this transition.

42

Despite TCU’s formal declaration of integration in 1964, athletics strategically dragged its feet.

The football arena constituted a space where community members could express and vocalize

their discontent. As SMU’s Jerry LeVias, the first African American athlete to receive a

scholarship in the Southwest Conference, experienced in 1965, TCU fans were not ready. LeVias

recalls his SMU years as a time of agony, due to the racist physical, mental, and emotional abuse

he suffered, including abuse from TCU athletes and fans. He was spat on and received death

threats when SMU played the Horned Frogs.

88

LeVias’s treatment highlighted the hatred visited

upon Blacks at this time, as well as the ethnophobic sentiment concerning physical proximity:

According to the Skiff, “Trainers wouldn’t tape his ankles for fear of touching his black skin.

Teammates emptied the showers when he stepped in.”

89

90

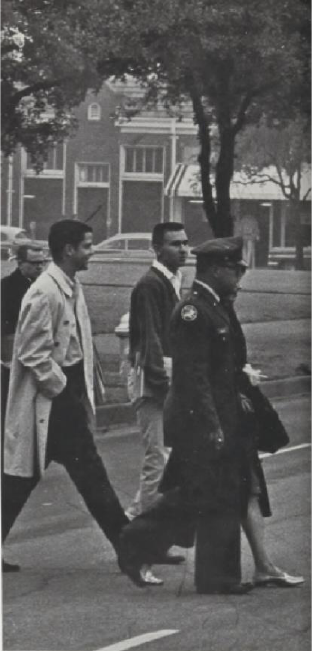

Figure 16: SMU Jerry LeVias chased by TCU Billy Lloyd, 1968

88

TCU officially apologized in 2003, after LeVias was inducted in the College Football Hall of Fame, The Skiff,

“Busting Through the Line,” September 21, 2007.

89

The Skiff, “Busting Through the Line,” September 21, 2007.

90

Fort Worth Star-Telegram Collection, University of Texas at Arlington Libraries. "SMU vs. TCU football game."

UTA Libraries Digital Gallery. 1968. Accessed June 23, 2023. https://library.uta.edu/digitalgallery/img/10000396

43

The same year that LeVias was drafted, TCU offered a basketball scholarship to James

Cash, a senior at I.M. Terrell High School, making him the first Black athlete at TCU and the

first African American basketball player in the Southwest Conference. He would later become

the first Black member of the TCU Board of Trustees and the first Black faculty member to

receive tenure at the Harvard Business School. In November 2022, TCU unveiled a statue of him

and hosted a ceremony where Cash received an honorary doctorate, a proclamation by Tarrant

County Commissioner Roy Brooks, and a proclamation by the Fort Worth Mayor Mattie Parker,

marking November 11, 2022, as Dr. James Cash Day. The statue of Dr. Cash is the first (and, to

date, only) campus monument that honors a person of color.

Figure 17: In 2021, Dr. Cash was bestowed the RRI Plume Award in Sarasota, FL

(Courtesy of TCU’s Race and Reconciliation Initiative)

44

Figure 18: The statue is located in the Schoellmaier Arena, along with other legends of TCU Athletics

(Courtesy of TCU Athletics/Sharon Ellman).

Like many of his peers in the TCU class of 1969, Cash has many fond memories of his

TCU years.

91

Although he experienced microaggressions, they occurred only occasionally; he

benefited from the privilege of being a student athlete for a sport that attracted relatively smaller

crowds, in comparison to football. Linzy Cole joined the Horned Frogs a year after Cash,

becoming the first Black football player at TCU. Like Jerry LeVias, Cole received death threats

to discourage him from playing on the field. Football crowds were ruthless. In a similar fashion,

TCU’s first Black cheerleader Ronnie Hurdle was not allowed to perform routines with white

female cheerleaders during football games. He also received death threats to bar his inclusion on

the field. Although he was elected to the squad in 1969, Hurdle was not a full participant until

late 1970, due to the omnipresent fear of interracial romance and unlawful miscegenation.

Likewise, in the autumn of 1970, Jennifer Giddings’s glorious crowning as the first Black

91

Interview with James I. Cash, by Sylviane Greensword and Frederick Gooding, Jr., Race and Reconciliation

Initiative Oral History Project, Texas Christian University. 2021.

https://repository.tcu.edu/handle/116099117/52346.

45

Homecoming Queen at TCU, and in the SWC, was somewhat dulled when Chancellor Moudy’s

greeting took the shape of a handshake instead of the expected traditional hug.

92

93

Figure 19: Linzy Cole, 1970

92

Interview with L. Michelle Smith, by Sylviane Greensword, Race and Reconciliation Initiative Oral History

Project, Texas Christian University. 2022. https://repository.tcu.edu/handle/116099117/52346.

93

The Horned Frog, TCU Yearbook, 1970, 74.

46

Figure 20: Attorney Hurdle visits the RRI Timeline Exhibit at the Mary Couts Burnett Library after an RRI Oral History Project

interview, 2021 (Courtesy of TCU’s Race and Reconciliation Initiative).

47

94

Figure 21: Jennifer Giddings Brooks greeted on the football field by Chancellor Moudy, 1970

The crowning of an African American Homecoming Queen contributed to TCU’s

reputation as a champion of diversity. Her race was not a hindrance to her popularity. Her afro-

styled hair (which was highly politicized in the 1970s) did not diminish her poise or her beauty.

These expressive liberties of ethnic and gender identity, however, did not extend to the football

team. In 1971, Coach Jim Pittman requested that all players should remain “well-groomed” and

clean shaven. While this appeared to be a race-neutral policy, a survey of the team rosters

revealed that all but one of the players with facial hair and voluminous hair were African

American. As they also underwent discrimination in their classrooms and other parts of student

life and were routinely denied food at the training tables, for many of these athletes, this was the

last straw.

95

In February, four football players -- Larry Dibbles, Ervin Garnett, Hodges Mitchell,

94

The Horned Frog. 1971, 38

95

SMU Jones Film, “WFAA February 3-4, 1971 Part 2,”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=80v1iY55qhE&t=428s.

48

and Ray Rhodes -- withdrew from the squad. Their position was that they should not be required

to sacrifice their performance of ethnicity (their afros) and their masculinity (their facial hair) in

order to be accepted.

96

Along with Jennifer Giddings and other Black student organization

leaders, the athletes addressed the campus community via a press conference, where they

itemized a list of ways that campus life needed to improve, particularly with regard to race-

related policies and practices.

97

The students requested an explanation for exclusion of Giddings

from the recent Cotton Bowl Parade. They also asked for the hiring of African American

counselors (a minister and a psychologist) as those would be more understanding and aware of

the challenges that Black students encounter in a Predominantly White Institution. In the area of

academics, the group called for a more inclusive curriculum, as well as an increased Black

faculty presence. Finally, they demanded more transparency concerning the rejected application

of Jimmy Leach, an African American whose enrollment was denied amidst allegations of

racism. The following table summarizes the demands addressed to the administration, as well as

their related outcomes.

1971 DEMAND

ADMINISTRATION RESPONSE

ADDITIONAL STUDENT

DEMAND

Revision of policy

changes and dress

codes in athletics are

discriminatory against

Blacks

1971

Athletic staff deny racial

motivations behind the code;

other coaches discuss

adopting the code but there

was no actual

implementation. Pittman’s

successor does not further

enforce the code, based on

roster photographs.

96

Three years earlier, a similar controversy had arisen - this time among mostly white students - as the Chancellor

Moudy and Dean of Men John Murray stated that faculty retained the right to deny classroom access to students

whose hairstyle did not convey “clear differentiation of the sexes” or whose facial hair “made one look like Buffalo

Bill.” The Skiff, “Faculty Retains Right To Make Hairy Decisions,” October 18, 1968, vol. 67, no. 9.

97

The Skiff, “Walkout Spurs Black Outcry,” February 5, 1971, vol. 69, no. 32.

49

An entire page in the

yearbook dedicated

to a public apology for

not allowing Jennifer

Giddings Brooks to

participate in the

Cotton Bowl parade

1971

No apology issued, as the

parade was traditionally

assigned to the TCU

Sweetheart instead of Miss

TCU.

Hiring a Black minister

1971-

1972

With Chancellor Moudy’s

“full blessing,” an unofficial

search committee led by

Campus Minister Roy

Martin

98

. Other committee

members are Dr.

Howard G. Wible, Dr. Curtis

Firkins from SAAC, and Mrs.

Allene Jones.

TCU hires a Black counselor,

Roy Maiden

Hiring a Black

psychologist

Hiring more Black

professors

1972

Vice Chancellor for Academic

Affairs states TCU is doing

“pretty well” and does not

intend to give preference to

Black applicants

99

.

1974

TCU’s NAACP files a

charge against the

university; TCU

retained its federal

funding.

2016

We demand that TCU

increase faculty of

color by at least 10%,

in addition the

retention rate

these faculty

members will remain

above 75%. (to reflect

the population of

Texas)

98

The Skiff, “Black Man Must Serve Whites Too,” April 2, 1971.

https://repository.tcu.edu/handle/116099117/15369.

99

The Skiff, “Answer in Sight for Black Woes,” February 2, 1971, vol. 69, no. 33.

https://repository.tcu.edu/handle/116099117/15354.

50

2021-

prese

nt

During the RRI-sponsored

annual Reconciliation Day,

the offices of Academic

Affairs and Human Resources

provide updates on the effort

to increase diversity in faculty

and administrative staff.

2020

We demand a public

written commitment

from Chancellor

Victor Boschini and

provost/vice

chancellor Teresa

Dahlberg

To increase faculty

diversity via cluster

hires across the

University and

additional tenure

track lines provided

to CRES

And WGST.

100

More Black-oriented

classes

1971

TCU attempts a Black Studies

minor administered by an all-

white faculty; the program

lasted only a decade as it had

little administrative and

financial support and

promotion

101

.

University Research

Foundation funds the Speech

Department’s experimental

intercultural communication

course. Dr. F. H. Goodyear is

the instructor of record

102

.

2017

Creation of two departments:

Comparative Race and Ethnic

Studies, and African

American and Africana

Studies

2016

New list of student

demands states: “We

demand that a

department of

diverse studies are

created along with an

Ethnic Studies

course that will be a

core curriculum

requirement for all

100

Coalition for University Justice & Equity (CUJE)

101

Louise Ferrie, The Skiff, “Black Minor Pass Next Fall,” April 2, 1971, 3.

https://repository.tcu.edu/handle/116099117/15369

102

Jon Shipley, The Skiff, “New Attitudes Crumble Racism,” March 20, 1973.

https://repository.tcu.edu/handle/116099117/15571

51

students. We also

demand a rigorous

reevaluation of the

courses that currently

fulfill the core

curriculum’s diversity

requirement, led by a

board comprised of

faculty of color who

would be

compensated for this

service."

“We demand that

TCU hire a Chief

Officer of Diversity

and Inclusion in

charge of

overseeing the

curriculums and

projects set forth in

this document.”

Investigation of

possible racist

motivations behind

Jimmy Leach’s denial

of enrollment

1971

The Business Office stated

that Leach’s denial of