NONBANK

MORTGAGE

SERVICERS

Existing Regulatory

Oversight Could Be

Strengthened

Report to Congressional Requesters

March 2016

GAO-16-278

United States Government Accountability Office

On April 14, 2016, this report was revised to insert “more” in the

recommendation on p. 49 to match the highlights and response to

agency comments and to modify the conclusions on p.48 to better align

with the recommendation.

United States Government Accountability Office

Highlights of GAO-16-278, a report to

congressional requesters

March 2016

NONBANK MORTGAGE SERVICERS

Existing Regulatory Oversight

Could Be

Strengthened

Why GAO Did This Study

As of June 2015, about a quarter of the

$9.9 trillion in outstanding home

mortgages in the United States were

serviced by nonbank servicers—non-

depository institutions that perform

such activities as collecting borrowers’

monthly payments and modifying loan

terms. After the 2007-2009 financial

crisis, an increase in delinquent loans

and other factors led some banks to

exit the mortgage servicing business

and created opportunities for increased

participation by nonbank entities. GAO

was asked to study the effects of the

growth of nonbank servicers in the

mortgage market. This report

examines, among other things, recent

trends in mortgage servicing and the

oversight framework in which nonbank

servicers operate. GAO analyzed

mortgage industry data from January

2006 through June 2015; reviewed

relevant laws and documents from

regulatory and housing agencies and

an industry group; conducted a

literature review; and interviewed

consumer groups, regulators and other

agency officials, and market

participants.

What GAO Recommends

Congress should consider granting

FHFA authority to examine third parties

that do business with the enterprises.

In addition, CFPB should take steps to

collect more data on the identity and

number of nonbank servicers. FHFA

agreed that there should be parity

among financial institution regulators in

oversight authority of regulated entities

and third parties they do business with.

CFPB agreed that more data could

supplement existing information but

noted that the current data limitation

does not materially affect its work.

What GAO Found

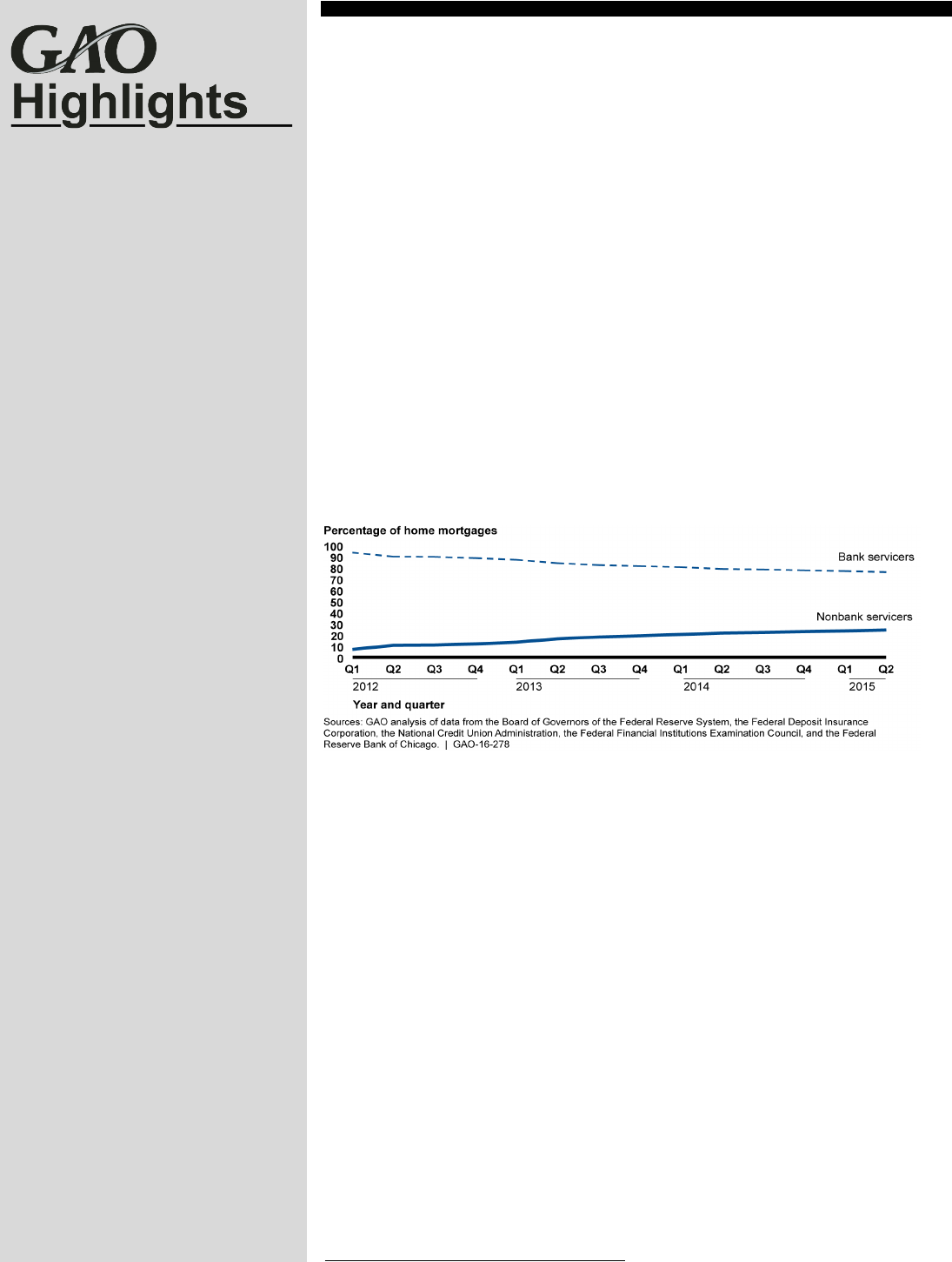

The share of home mortgages serviced by nonbanks increased from

approximately 6.8 percent in 2012 to approximately 24.2 percent in 2015 (as

measured by unpaid principal balance). However, banks continued to service the

remainder (about 75.8 percent). Some market participants GAO interviewed said

nonbank servicers’ growth

increased the capacity for servicing delinquent loans,

but they also noted challenges. For example, rapid growth of some nonbank

servicers did not always coincide with their use of more advanced operating

systems or effective internal controls to handle their larger portfolios—an issue

identified by the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) and others.

Share of Home Mortgages Serviced by Bank and Nonbank Servicers, from First Quarter 2012

through Second Quarter 2015

Note: GAO measured the quantity of mortgages using the total unpaid principal balance of all home

mortgage loans outstanding. GAO estimated the amount of mortgages serviced by banks as the sum

of the unpaid principal balance of mortgages that banks report holding for investment, sale, or trading

plus the unpaid principal balance of mortgages that banks report servicing for others. GAO estimated

the amount of mortgages serviced by nonbank servicers as the difference between the total amount

of mortgages outstanding and the amount serviced by banks.

Nonbank servicers are generally subject to oversight by federal and state

regulators and monitoring by market participants, such as Fannie Mae and

Freddie Mac (the enterprises). In particular, CFPB directly oversees nonbank

servicers as part of its responsibility to help ensure compliance with federal laws

governing mortgage lending and consumer financial protection. However, CFPB

does not have a mechanism to develop a comprehensive list of nonbank

servicers and, therefore, does not have a full record of entities under its purview.

As a result, CFPB may not be able to comprehensively enforce compliance with

consumer financial laws. In addition, the Federal Housing Finance Agency

(FHFA) is the safety and soundness regulator of the enterprises. As such, it has

indirect oversight of third parties that do business with the enterprises, including

nonbanks that service loans on the enterprises’ behalf. However, in contrast to

bank regulators, FHFA lacks statutory authority to examine these third parties to

identify and address deficiencies that could affect the enterprises. GAO has

previously determined that a regulatory system should ensure that similar risks

and services are subject to consistent regulation and that a regulator should have

sufficient authority to carry out its mission. Without such authority, FHFA may

lack a supervisory tool to help it more effectively monitor third parties’ operations

and the enterprises’ actions to manage any associated risks.

View GAO-16-278. For more information,

contact

Lawrance L. Evans Jr., (202) 512-

8678, or

Page i GAO-16-278 Nonbank Servicers

Letter 1

Background 4

Nonbank Servicers’ Share of Mortgage Servicing Has Increased,

and Their Characteristics Vary 8

Nonbank Servicer Growth Poses Both Benefits and Challenges for

Market Participants and Consumers 20

Nonbank Mortgage Servicers Are Generally Subject to Federal,

State and Market Oversight, but Some Limitations Exist 31

Conclusions 48

Matter for Congressional Consideration 49

Recommendation for Executive Action 49

Agency Comments and Our Evaluation 49

Appendix I Objectives, Scope, and Methodology 53

Appendix II GAO Analysis of Market Concentration 65

Appendix III Nonbank Servicers Identified during Audit 68

Appendix IV Comments from the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau 88

Appendix V Comments from the Conference of State Bank Supervisors 91

Appendix VI Comments from the Federal Housing Finance Agency 94

Appendix VII Comments from Ginnie Mae 95

Appendix VIII GAO Contacts and Acknowledgements 96

Contents

Page ii GAO-16-278 Nonbank Servicers

Tables

Table 1: Shares of Home Mortgages Serviced by the 20 Largest

Servicers, 2012Q1 and 2015Q2 10

Table 2: Percentage of Home Mortgages in Ginnie Mae and

Enterprise MBS and Enterprise Portfolios Serviced by

Nonbank Servicers, as of Second quarter 2015 15

Table 3: Select Nonbanks Servicers Identified through Ginnie Mae

and the Enterprises by Location 69

Figures

Figure 1: Mortgage Servicing 5

Figure 2: Share of Home Mortgages Serviced by the 10 Largest

Nonbank Servicers, as of 2015Q2 12

Figure 3: Share of Home Mortgages Serviced by Bank and

Nonbank Servicers, from 2012Q1 to 2015Q2 13

Figure 4: Map of State, District and United States Territory

Mortgage Servicing Licensing Requirements as of June

2015 34

Figure 5: Percentage of Home Mortgages Owned or Guaranteed

by Entity, as of 2015Q2 40

Figure 6: Concentration in the Market for Mortgage Servicing, from

Fourth Quarter 2006 through Fourth Quarter 2014 67

Page iii GAO-16-278 Nonbank Servicers

Abbreviations

CFPB Consumer Financial Protection Bureau

CSBS Conference of State Bank Supervisors

Dodd-Frank Act Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer

Protection Act

DOJ Department of Justice

enterprises Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac

Federal Reserve Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System

FHA Federal Housing Administration

FHFA Federal Housing Finance Agency

FSOC Financial Stability Oversight Council

FTC Federal Trade Commission

Ginnie Mae Government National Mortgage Association

HHI Herfindahl-Hirschman Index

HMDA Home Mortgage Disclosure Act

HUD Department of Housing and Urban Development

IMF Inside Mortgage Finance

LEI legal entity identifier

MBS mortgage-backed securities

MSR mortgage servicing rights

NIC National Information Center

NMLS Nationwide Multistate Licensing System

OCC Office of the Comptroller of the Currency

SNL SNL Financial

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the

United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety

without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain

copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be

necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

Page 1 GAO-16-278 Nonbank Servicers

441 G St. N.W.

Washington, DC 20548

March 10, 2016

The Honorable Elizabeth Warren

United States Senate

The Honorable Elijah E. Cummings

Ranking Member

Committee on Oversight and Government Reform

House of Representatives

As of June 2015, about a quarter of the $9.9 trillion in outstanding home

mortgage loans in the United States were serviced by nonbank

servicers.

1

Historically, commercial banks, thrifts, and credit unions have

been the primary servicers of mortgage loans, performing activities such

as collecting payments from borrowers. However, rising mortgage

delinquencies during the 2007-2009 financial crisis and subsequent new

capital requirements have led banks to re-evaluate the benefits and costs

of retaining mortgages and the right to service them in their portfolios, and

some have reduced the percentage of their mortgage servicing business.

2

These dynamics have created opportunities for nonbank servicers to

increase their presence in the mortgage loan servicing market. Banks and

nonbank servicers are subject to different safety and soundness

regulation and different capital rules. As a result, mortgage market

1

We defined banks as bank holding companies, financial holding companies, savings and

loan holding companies, insured depository institutions, and credit unions, including any

subsidiaries or affiliates of these types of institutions. For the purposes of this report, we

refer to these entities collectively as “banks.” We define nonbank servicers as entities that

are not bank servicers.

2

In 2010, the Basel Committee (the global standard-setter for prudential bank regulation)

issued the Basel III framework—comprehensive reforms to strengthen global capital and

liquidity standards with the goal of promoting a more resilient banking sector. In 2013,

federal banking regulators adopted regulations to implement the Basel III based capital

standards in the United States, which generally apply to U.S. bank holding companies and

banks and are being phased in until 2019. Regulatory Capital Rules: Regulatory Capital,

Implementation of Basel III, Capital Adequacy, Transition Provisions, Prompt Corrective

Action, Standardized Approach for Risk-weighted Assets, Market Discipline and

Disclosure Requirements, Advanced Approaches Risk-Based Capital Rule, and Market

Risk Capital Rule, 78 Fed. Reg. 62018 (Oct. 11, 2013). For a more complete discussion of

Basel III, see GAO, Bank Capital Reforms: Initial Effects of Basel III on Capital, Credit,

and International Competitiveness, GAO-15-67 (Washington, D.C.: Nov. 20, 2014).

Letter

Page 2 GAO-16-278 Nonbank Servicers

participants and others have questioned the extent to which nonbank

servicers may pose additional risk to consumers and the market and

whether the existing oversight framework can ensure the safety and

soundness of nonbank servicers.

You asked us to conduct a study of the effect of the increased presence

of nonbank mortgage servicers in the mortgage market. This report

examines (1) the characteristics of nonbank mortgage servicers and the

recent trends in the mortgage servicing industry, (2) the effect of nonbank

servicers on consumers and the mortgage market, and (3) the oversight

framework for nonbank servicers.

To address these objectives, we reviewed studies by GAO and relevant

literature on nonbank servicers and the mortgage market. As a part of this

review, we selected academic studies and research by industry

organizations, federal agencies, and others since the 2007-2009 financial

crisis on the mortgage servicing market with a focus on the role of

nonbank servicers. We analyzed data for 2006 through June 2015 from

the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (Federal

Reserve), Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac (the enterprises), the

Government National Mortgage Association (Ginnie Mae), and others to

identify trends in the mortgage servicing market and in particular nonbank

servicers. We assessed the reliability of these data by reviewing relevant

documentation, and we electronically tested the data for missing values,

outliers, and obvious errors, as well as interviewed knowledgeable

agency officials on how the data were prepared. We determined that data

were sufficiently reliable for our purposes. We reviewed relevant federal

regulations that govern the operations of mortgage servicers. We also

reviewed applicable guidance documents from the enterprises on the

operational and financial requirements of their servicers. In addition, we

reviewed examinations of nonbank servicers by the Bureau of Consumer

Financial Protection, also known as the Consumer Financial Protection

Bureau (CFPB) to learn about nonbank servicers’ deficiencies identified

by CFPB and as evidence of CFPB’s oversight. Furthermore, we

interviewed representatives from 10 nonbank servicers to obtain

information related to all three objectives. These included 9 of the 10

largest nonbank servicers (which serviced approximately 77.6 percent of

the total outstanding unpaid principal balance serviced by all nonbank

servicers as of December 31, 2014) and the largest nonbank sub-servicer

(a third-party mortgage servicer that has no fiduciary ties to or investment

Page 3 GAO-16-278 Nonbank Servicers

in the loans they service) based on outstanding unpaid principal balance

from Inside Mortgage Finance as of March 31, 2015.

3

In addition, we interviewed federal agency officials from CFPB and the

Federal Housing Finance Agency (FHFA) on their role in the regulatory

oversight of nonbank servicers and the enterprises, respectively. We also

interviewed officials from the Conference of State Bank Supervisors

(CSBS), an industry group that represents state financial regulators, as

well as state regulators from four states on their role in the oversight of

nonbank servicers.

4

In addition, we interviewed various mortgage market

participants regarding mortgage market trends and the potential effects of

mortgage servicing regulations as well as new and proposed financial

requirements for mortgage servicers. These participants include

representatives from the enterprises; Ginnie Mae; the Federal Housing

Administration (FHA) and other federal agencies that insure the loans in

Ginnie Mae-guaranteed mortgage-backed securities (MBS); industry

organizations that represent banks and mortgage servicers; two rating

agencies that rate MBS performance; third parties in the mortgage

servicing industry, such as mortgage servicing brokers and market

researchers; and companies that invest in or provide advice about

mortgage servicing rights (MSR), such as a real estate investment trust.

5

Further, we interviewed academics who have conducted research on the

nonbank mortgage servicing industry as well as consumer groups.

Appendix I provides a more detailed description of our scope and

methodology.

We conducted this performance audit from February 2015 to March 2016

in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards.

3

For the purposes of this report, unpaid principal balance is the total remaining dollar

amount owed by borrowers on home mortgage loans in the United States or its affiliated

areas.

4

We selected a purposive, geographically diverse sample of state regulators to interview

based on the data from the Conference of State Bank Supervisors about state licensing

practices. We selected two states that issue licenses specific to mortgage servicing but

only one state (New York) responded; one state (California) that licenses mortgage

servicers through a general licensing authority that may allow mortgage activities in

addition to servicing; and two states (Colorado and Virginia) that do not require specific

licenses for nonbank servicers.

5

We selected a purposive, nongeneralizeable sample of relevant types of mortgage

market participants based on their knowledge, expertise and role in the mortgage

servicing industry.

Page 4 GAO-16-278 Nonbank Servicers

Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain

sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our

findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that

the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and

conclusions based on our audit objectives.

The U.S. housing finance system is complex and has numerous public

and private participants that operate in both primary and secondary

markets.

6

In the primary market, lenders make loans—known as

mortgage loans—to borrowers that are secured by property in a process

known as mortgage loan origination. Originators can choose to hold

mortgages in their own portfolios or sell them into the secondary market.

When loans are sold in the secondary market, they are generally

packaged together into pools and held in trusts pursuant to terms and

conditions set out in an underlying pooling and servicing agreement.

Pools of loans are the assets backing the MBS that are issued and sold to

investors, who are entitled to the cash flow generated by loans in the

trust.

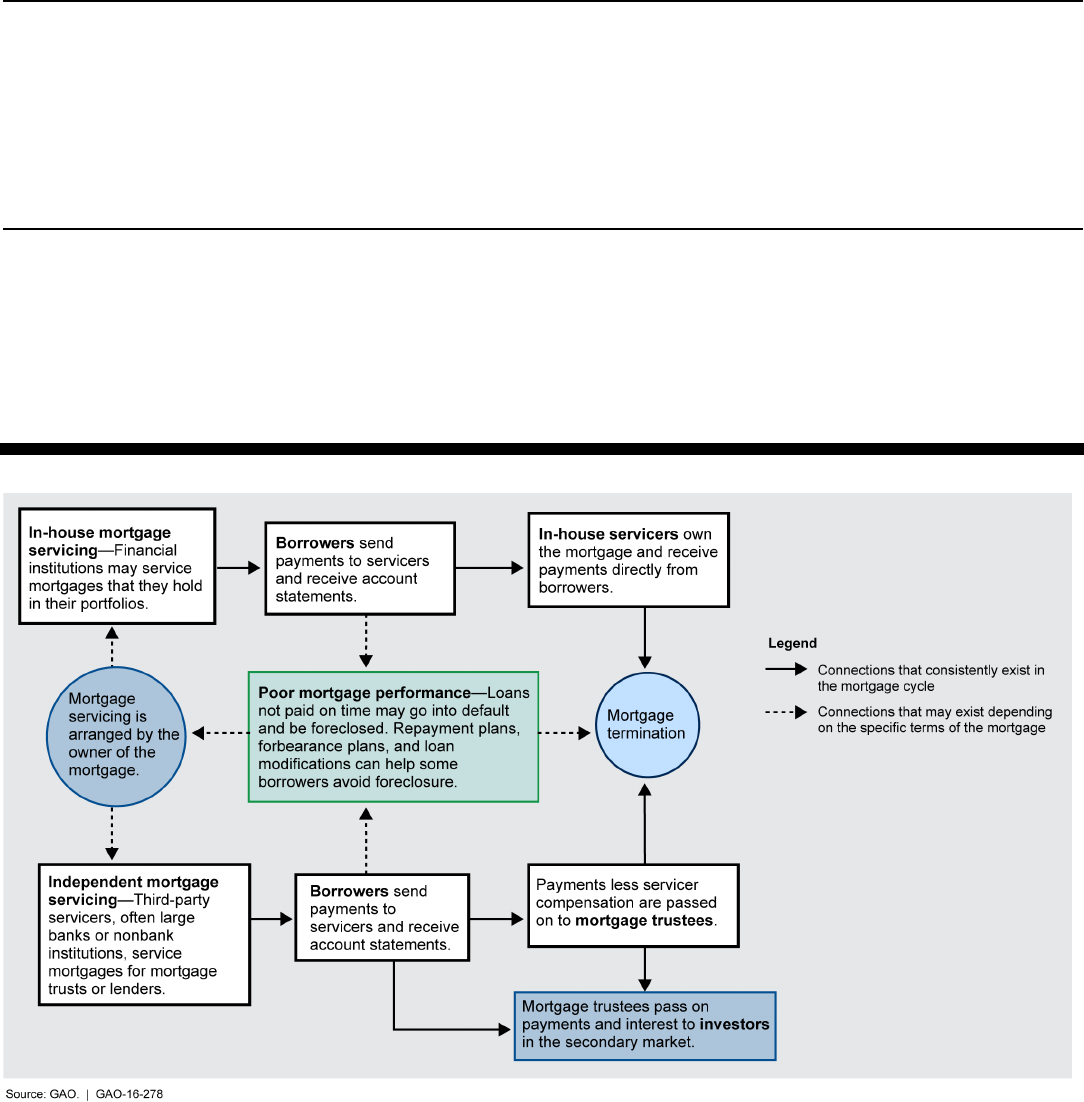

After the loan origination process is complete, the loan must be serviced

until it is terminated—through payment in full or foreclosure (see fig. 1).

Servicing is inherent in all mortgage loans, but the right to service a

mortgage becomes a distinct asset—an MSR—when contractually

separated from the loan when the loan is sold or securitized. Originators

can service mortgage loans that they originate or purchase, or they can

sell the mortgage loans but retain the MSR. Servicers other than the

originator may also purchase MSR on securitized loans or may be hired

to service loans for others. Servicers perform various loan management

functions, including collecting payments from the borrower until the

mortgage debt is satisfied or terminated, sending borrowers monthly

account statements and tax documents, responding to customer service

6

For a more complete discussion of the primary and secondary mortgage markets, see

GAO, Housing Finance System: A Framework for Assessing Potential Changes,

GAO-15-131 (Washington, D.C.: Oct. 7, 2014) and Sean M. Hoskins, Katie Jones, and N.

Eric Weiss, Congressional Research Service, An Overview of the Housing Finances

System in the United States, R42995 (Washington, D.C.: Feb. 19, 2015).

Background

Mortgage Market Structure

and Participants

Page 5 GAO-16-278 Nonbank Servicers

inquiries, maintaining escrow accounts for property taxes and hazard

insurance, and forwarding monthly mortgage payments to the loan

owners. In the event that borrowers become delinquent on their loan

payments, servicers may also initiate a range of actions, from offering a

workout option to allow the borrower to stay in the home to foreclosure

proceedings. In most instances, the MSR is revocable by the owner, who

may terminate the right to service for cause or without cause.

Figure 1: Mortgage Servicing

Participants in the secondary market include the enterprises or other

institutions that issue MBS, Ginnie Mae, investors, and credit rating

agencies.

• The enterprises purchase mortgages that meet their underwriting

criteria. They either hold these mortgages in their own portfolios or

pool them into MBS, guaranteeing that investors will receive timely

principal and interest payments even if the borrowers become

delinquent. On September 6, 2008, FHFA placed the enterprises into

Page 6 GAO-16-278 Nonbank Servicers

conservatorship out of concern that their deteriorating financial

condition threatened the stability of financial markets. As a result, the

enterprises now have explicit federal backing. The enterprises have

guidelines for servicers that service the loans in their MBS programs.

• Ginnie Mae, a federal agency within the Department of Housing and

Urban Development (HUD), guarantees the timely principal and

interest payments to investors in securities issued by approved

institutions through its MBS program. Ginnie Mae-guaranteed MBS

are composed exclusively of mortgages issued by private institutions

with its approval and guaranteed by the Department of Veterans

Affairs or insured by the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Rural

Housing Service, HUD’s Office of Public and Indian Housing, or FHA.

Ginnie Mae’s guarantee is explicitly backed by the full faith and credit

of the federal government. Ginnie Mae also has guidelines for

servicers that service the loans in its MBS program.

• Other private institutions, such as investment banks, may also issue

securities known as private-label MBS—that is, MBS not guaranteed

by Ginnie Mae or issued by the enterprises. Private-label MBS are

governed by pooling and servicing agreements specifying investors’

expectations for servicers.

• Credit rating agencies are companies that assess the creditworthiness

of debt securities, including MBS, and their issuers.

Various institutions service loans and can be classified into two groups:

banks and nonbanks. Bank and nonbank servicers have different basic

business models. Banks offer a variety of financial products to

consumers, including deposit products, loan products such as mortgage

and auto loans, and credit card products. In contrast, nonbank servicers

are generally involved only in mortgage-related activities and do not offer

deposit to consumers. Nonbank servicers may be involved in a variety of

mortgage activities, including servicing and originating loans, as well as

buying and selling MSR. For example, banks and other financial

companies may use nonbank servicers to service mortgages they

originate or own. Some nonbank servicers may also use nonbank sub-

servicers, which are third-party servicers that have no fiduciary ties to or

investment in the loans they service.

Page 7 GAO-16-278 Nonbank Servicers

CFPB enforces various federal laws and regulations governing mortgage

lending and servicing and consumer financial protection. CFPB was

created by the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection

Act (Dodd-Frank Act) and has rulemaking authority to implement

provisions of federal consumer financial law and primary enforcement

authority to assess compliance with various mortgage servicing rules.

7

CFPB also examines entities for compliance with federal consumer

financial laws, collects consumer complaints regarding debt collection and

other consumer financial products or services, and educates consumers

about their rights under federal consumer financial protection laws.

8

The Housing and Economic Recovery Act of 2008 established FHFA as

an independent agency to supervise and regulate the enterprises and the

Federal Home Loan Bank System.

9

FHFA has a statutory responsibility to

ensure that the enterprises operate in a safe and sound manner and that

the operations and activities of each regulated entity foster liquid,

efficient, competitive, and resilient national housing finance markets.

In addition to the federal regulators, state regulators supervise entities

that are chartered or licensed in their states to offer products and services

related to the mortgage industry. State regulators may also coordinate

some regulatory activities through their participation in various industry

organizations, including CSBS, a nationwide organization of state

financial regulators that helps coordinate state financial regulation,

including over mortgage servicing.

10

CSBS activities include the

development of legislative, regulatory, and supervisory solutions, which

states can choose whether and how to adopt.

7

Pub. L. No. 111-203, § 1021, § 1024, 124 Stat. 1376 1980, 1987 (2010) (codified at 12

U.S.C. § 5511, § 5514).

8

§ 1011, § 1024, 124 Stat.at 1964, 1987 (2010) (codified at 12 U.S.C. § 5491, § 5514).

9

Pub. L. No. 110-289, § 1101, 122 Stat. 2654, 2661 (codified at 12 U.S.C. § 4511).

10

CSBS regulator members also include members from the District of Columbia, Guam,

Puerto Rico, and the U.S. Virgin Islands.

Nonbank Servicer

Regulators

Consumer Financial Protection

Bureau

Federal Housing Finance

Agency

State Regulators

Page 8 GAO-16-278 Nonbank Servicers

As we have previously reported, the dramatic decline in the U.S. housing

market that began in 2006 precipitated a decline in the price of mortgage-

related assets, particularly mortgage assets based on nonprime loans in

2007.

11

Some financial institutions found themselves so exposed that they

were threatened with failure, and some failed because they were unable

to raise capital or obtain liquidity as the value of their portfolios declined.

Other institutions, ranging from the enterprises to large securities firms,

were left holding “toxic” mortgages or mortgage-related assets that

became increasingly difficult to value, were illiquid, and potentially had

little worth. Moreover, investors not only stopped buying private-label

securities backed by mortgages but also became reluctant to buy

securities backed by other types of assets. Because of uncertainty about

the liquidity and solvency of financial entities, the prices banks charged

each other for funds rose dramatically, and interbank lending conditions

deteriorated sharply. The resulting liquidity and credit crunch made the

financing on which businesses and individuals depend increasingly

difficult to obtain. By late summer of 2008, the ramifications of the

financial crisis ranged from the continued failure of financial institutions to

increased losses of individual wealth and reduced corporate investments

and further tightening of credit that would exacerbate the emerging global

economic slowdown.

11

GAO, Financial Institutions: Causes and Consequences of Recent Bank Failures,

GAO-13-71 (Washington, D.C.: Jan. 3, 2013).

Mortgage-Related Assets

and the 2007-2009

Financial Crisis

Nonbank Servicers’

Share of Mortgage

Servicing Has

Increased, and Their

Characteristics Vary

Page 9 GAO-16-278 Nonbank Servicers

From 2012 to the second quarter of 2015, the mortgage servicing market

appears to have become less concentrated while the share of mortgages

serviced by nonbank servicers appears to have increased.

12

Our analysis

suggests that the share of all mortgages serviced by nonbank servicers

increased from approximately 6.8 percent in the first quarter of 2012 to

approximately 24.2 percent in the second quarter of 2015.

13

Our analysis

also suggests that, when viewed at the national level, the mortgage

servicing industry was relatively unconcentrated in 2012 and has become

less concentrated since then.

14

Market concentration is an indicator of the

extent to which firms in a market can exercise power by raising prices,

reducing output, diminishing innovation, or otherwise harming customers

as a result of reduced competitiveness. In a concentrated market, a small

number of entities account for a large share of the market, which

increases their ability to exercise market power. In contrast, our analysis

suggests that the mortgage servicing industry is relatively

unconcentrated, at least when viewed at the national level. This finding

suggests that servicers have less ability to exercise market power and are

more likely to behave competitively.

15

A number of academic studies and

reports have also noted the increase in the share of mortgages serviced

12

For the purposes of this report, we consider mortgages to be home mortgage loans,

defined as loans secured by residential properties. These include loans secured by

properties with up to four units and farm houses, as well as home equity loans and home

equity lines of credit, but exclude other loans (i.e., those secured by multifamily,

commercial, and other farm properties).

13

We estimated that nonbank servicers were servicing about $729 billion of $10,643 billion

in total outstanding mortgages as of the first quarter of 2012 and about $2,392 billion of

$9,900 billion in the second quarter of 2015. These estimates are based on the difference

between total outstanding mortgages and the sum of (1) mortgages held for investment,

sale, or trading by bank servicers and (2) mortgages serviced for others by bank servicers.

We assumed that banks service the mortgages they hold for investment, sale, or trading.

To the extent that they do not do so, our estimates understate the amount of mortgages

serviced by nonbanks. Dollar amounts are adjusted for inflation and expressed in second

quarter 2015 dollars.

14

Our market concentration analysis was based on a widely accepted measure employed

by federal agencies to assess market concentration. A key assumption of our analysis is

that the mortgage servicing market is national in scope. However, the mortgage servicing

market may be segmented by regions, states, or other subnational areas, and the results

of our analysis may not reflect trends in mortgage servicing industry concentration in those

areas. The details of our analysis and its limitations can be found in appendix II.

15

Department of Justice and Federal Trade Commission guidelines, which we considered

in our analysis, classify markets into 3 types: unconcentrated, moderately concentrated,

and highly concentrated.

Nonbank Servicers’ Share

of Mortgages Has

Increased Since 2012

Page 10 GAO-16-278 Nonbank Servicers

by nonbank servicers, and some market participants have attributed the

decline in market concentration to this growth.

16

A growing number of the largest servicers are nonbank servicers. For

example, as of June 2015, the 20 largest servicers accounted for nearly

63 percent of all mortgages serviced.

17

Table 1 shows the shares of

mortgages serviced by the 20 largest servicers for the first quarter of

2012 and the second quarter of 2015. As an indicator of their larger role

in the market, the number of nonbank servicers among the 20 largest

mortgage servicers increased from 6 in the first quarter of 2012 to 9 in the

second quarter of 2015.

Table 1: Shares of Home Mortgages Serviced by the 20 Largest Servicers, 2012Q1 and 2015Q2

2012Q1

2015Q2

Rank

Servicer

Share (percent)

Servicer

Share (percent)

1

Wells Fargo & Company

18.0%

Wells Fargo & Company

17.1%

2

Bank of America Mtg. & Affiliates

16.5

Chase

9.3

3

Chase

10.8

Bank of America Mtg. & Affiliates

6.2

4

Citi

5.0

Nationstar Mortgage LLC

4.1

5

Ally Financial

3.6

Ocwen Financial Corporation

3.2

6

US Bank Home Mortgage

2.4

Citi

3.1

7

PHH Mortgage

1.8

US Bank Home Mortgage

2.9

8

SunTrust Mortgage, Inc.

1.5

Walter Investment Management

2.5

9

PNC Mortgage

1.3

PHH Mortgage

2.3

10

OneWest Bank

1.2

Quicken Loans, Inc.

1.8

11

Nationstar Mortgage LLC

1.0

SunTrust Mortgage, Inc.

1.5

12

HSBC North America

0.9

PennyMac Loan Services

1.4

13

Ocwen Financial

0.9

PNC Mortgage

1.3

16

For example, in a July 2014 report, the FHFA Office of Inspector General found that

among the 30 largest servicers, nonbank servicers were servicing 6 percent of mortgages

at the end of 2011 and 17 percent at the end of 2013. See Federal Housing Finance

Agency Office of Inspector General, FHFA Actions to Manage Enterprise Risks from

Nonbank Servicers Specializing in Troubled Mortgages, AUD-2014-014 (Washington,

D.C.: July 1, 2014).

17

Inside Mortgage Finance, Issue 2015:36 (Bethesda, Md.: Inside Mortgage Finance

Publications, 2015); Inside Mortgage Finance, Issue 2012:20 (Bethesda, Md.: Inside

Mortgage Finance Publications, 2012).

Page 11 GAO-16-278 Nonbank Servicers

14

BB&T Mortgage

0.9

BB&T Mortgage

1.2

15

MetLife Home Loans

0.9

LoanCare, LLC

1.2

16

Walter Investment Management

0.8

Provident Funding

0.8

17

Flagstar Bank

0.7

Fifth Third Bank

0.8

18

Fifth Third Bank

0.7

Flagstar Bank

0.8

19

Capital One Financial

0.7

Caliber Home Loans

0.8

20

American Home Mortgage Servicing

0.7

HSBC North America

0.6

Aggregate share of the 20 largest servicers

70.5

62.6

Legend: shading = nonbank servicer

Source: GAO analysis of Inside Mortgage Finance data. | GAO-16-278

Note: We used data from Inside Mortgage Finance to determine the shares of mortgages serviced by

the 20 largest servicers, based on unpaid principal balance, and the number of nonbank servicers

among the 20 largest servicers for the first quarter of 2012 and the second quarter of 2015. We

defined banks as bank holding companies, financial holding companies, savings and loan holding

companies, insured depository institutions, and credit unions, including any subsidiaries or affiliates of

these types of institutions. We define nonbank servicers as entities that are not bank servicers.

Correspondingly, we found that a few nonbank servicers account for the

majority of the total share of mortgages serviced by nonbank servicers.

Our analysis shows that the 10 largest nonbank servicers were servicing

about 76.4 percent of the share of mortgages serviced by all nonbank

servicers as of the second quarter of 2015 (see fig. 2).

18

18

Inside Mortgage Finance, Issue 2015:36.

Page 12 GAO-16-278 Nonbank Servicers

Figure 2: Share of Home Mortgages Serviced by the 10 Largest Nonbank Servicers,

as of 2015Q2

Note: We used the unpaid principal balance of outstanding home mortgage loans to estimate the

shares of home mortgage loans serviced by bank and nonbank servicers for the second quarter of

2015. We defined banks as bank holding companies, financial holding companies, savings and loan

holding companies, insured depository institutions, and credit unions, including any subsidiaries or

affiliates of these types of institutions. We define nonbank servicers as entities that are not bank

servicers. We measured the quantity of home mortgage loans using the total unpaid principal balance

of all outstanding home mortgage loans. We estimated the amount of home mortgage loans serviced

by banks as the sum of the unpaid principal balance of home mortgage loans that banks report

holding for investment, sale, or trading plus the unpaid principal balance of home mortgage loans that

banks report servicing for others. We estimated the amount of home mortgage loans serviced by

nonbank servicers as the difference between the total amount of outstanding home mortgage loans

and the amount serviced by banks. We estimated the share of home mortgage loans serviced by

nonbank servicers as the percentage of total unpaid principal balance serviced by nonbank servicers.

We then estimated the amount of home mortgage loans being serviced by the 10 largest nonbank

servicers using data from Inside Mortgage Finance on the 100 largest mortgage servicers. We

estimated the share of home mortgage loans being serviced by the 10 largest nonbanks as a

percentage of the unpaid principal balance being serviced by all nonbank servicers.

Although our analysis shows that bank servicers’ share of aggregate

mortgages has decreased since the first quarter of 2012, banks still

service a majority of mortgages. Figure 3 shows that banks serviced

about 75.8 percent of mortgages as of the second quarter of 2015.

Further, although we found that the aggregate share of mortgages

serviced by nonbank servicers has grown, the largest bank servicers’

individual shares remain much larger than the individual shares of the

largest nonbank servicers. For example, the largest bank servicer

Page 13 GAO-16-278 Nonbank Servicers

serviced about 17.1 percent of mortgages as of the second quarter of

2015, compared to about 4.1 percent of mortgages for the largest

nonbank servicer (see table 1).

19

An exception to this trend was the

subprime segment of the mortgage servicing industry, where one

nonbank servicer accounted for over 28 percent of all subprime

mortgages serviced in 2014—exceeding the amount serviced by the two

largest bank servicers combined.

20

Figure 3: Share of Home Mortgages Serviced by Bank and Nonbank Servicers, from

2012Q1 to 2015Q2

Note: We used the unpaid principal balance of outstanding home mortgage loans to estimate the

shares of home mortgage loans serviced by bank and nonbank servicers for each quarter for the

19

Inside Mortgage Finance, Issue 2015:36.

20

Inside Mortgage Finance, Mortgage Market Statistical Annual 2015 Yearbook,

(Bethesda, Md: Inside Mortgage Finance Publications, 2015). This nonbank servicer has

been selling its MSR for Ginnie Mae, Fannie Mae, and Freddie Mac MBS since December

2014.

Page 14 GAO-16-278 Nonbank Servicers

period from 2012Q1 to 2015Q2. We defined banks as bank holding companies, financial holding

companies, savings and loan holding companies, insured depository institutions, and credit unions,

including any subsidiaries or affiliates of these types of institutions. We define nonbank servicers as

entities that are not bank servicers. We measured the quantity of home mortgage loans using the

total unpaid principal balance of all outstanding home mortgage loans. We estimated the amount of

home mortgage loans serviced by banks as the sum of the unpaid principal balance of home

mortgage loans that banks report holding for investment, sale, or trading plus the unpaid principal

balance of home mortgage loans that banks report servicing for others. We estimated the share of

home mortgage loans serviced by bank servicers as the percentage of the total unpaid principal

balance serviced by bank servicers. We estimated the amount of home mortgage loans serviced by

nonbank servicers as the difference between the total amount of outstanding home mortgage loans

and the amount serviced by banks. We estimated the share of home mortgage loans serviced by

nonbank servicers as the percentage of the total unpaid principal balance serviced by nonbank

servicers.

While nonbank servicers account for less than a quarter of the overall

mortgage servicing market, their share of particular market segments has

increased significantly. Specifically, as of the second quarter of 2015,

nonbank servicers serviced 35 percent of mortgages in Ginnie Mae and

enterprise MBS and enterprise-owned portfolios (see table 2) compared

to their overall share of 24.2 percent. Additionally, the share of mortgages

in Ginnie Mae MBS serviced by nonbank servicers, as measured by the

unpaid principal balance, grew to about 42 percent in the second quarter

of 2015, up from about 25 percent in the fourth quarter of 2006.

21

Similarly, nonbank servicers own the majority of the MSR related to

private-label securities, although this market segment is relatively small

as discussed later. According to one 2015 study, nonbank servicers own

the MSR associated with approximately 74 percent of loans in pools of

private-label securities.

22

21

On the basis of our analysis, we estimate that there were about 640 nonbank servicers

eligible to service for Ginnie Mae, Fannie Mae, or Freddie Mac for this period. We define

an eligible nonbank servicer as one that was servicing, or was approved to service,

mortgages in Ginnie Mae or enterprise MBS or enterprise-owned portfolios as of the

second quarter of 2015.

22

Mortgage Bankers Association and PricewaterhouseCoopers, The Changing Dynamics

of the Mortgage Servicing Landscape, (Washington, DC: June 2015).

Page 15 GAO-16-278 Nonbank Servicers

Table 2: Percentage of Home Mortgages in Ginnie Mae and Enterprise MBS and

Enterprise Portfolios Serviced by Nonbank Servicers, as of Second quarter 2015

Percentage of unpaid principal

balance serviced

Ginnie Mae-guaranteed MBS

41.9%

Fannie Mae MBS and portfolios

37.4

Freddie Mac MBS and portfolios

25.2

All Ginnie Mae and enterprise MBS and enterprise

portfolios

a

35%

Source: GAO analysis of data from Ginnie Mae, Fannie Mae, and Freddie Mac. | GAO-16-278

Note: We defined banks as bank holding companies, financial holding companies, savings and loan

holding companies, insured depository institutions, and credit unions, including any subsidiaries or

affiliates of these types of institutions. We define nonbank servicers as entities that are not bank

servicers. Ginnie Mae and Fannie Mae each provided us with data on the total unpaid principal

balance of mortgages serviced by all of their approved servicers and their approved nonbank

servicers, which we used to calculate the percentage of home mortgages serviced by nonbank

servicers. We calculated this percentage for Freddie Mac using servicer-level data on unpaid principle

balance provided to us by Freddie Mac. We used an SNL Financial list of banks as well as Freddie

Mac data fields that indicated institution type, to determine which of Freddie Mac’s servicers met our

definition for bank and nonbank servicers.

a

This percentage was calculated using all home mortgage loans in Ginnie Mae and enterprise MBS

and enterprise portfolios that nonbanks were servicing as of the section quarter of 2015.

FHFA officials and representatives from Freddie Mac and one nonbank

servicer we interviewed suggested that the increase in the share of

mortgages serviced by nonbank servicers occurred as a result of the

increase in delinquent loans following the 2007-2009 crisis. Further, those

officials and representatives, as well as studies we reviewed, cited

nonbank servicers’ willingness and capability to service delinquent loans

during the financial crisis as one reason for their growth (as discussed

later, some nonbank servicers specialize in servicing delinquent loans),

explaining that many banks transferred MSR for delinquent portfolios to

nonbank servicers during this time.

23

Additionally, we previously reported

23

We have ongoing work to further study the potential factors influencing banks’ decisions

about whether to hold or sell MSR.

Page 16 GAO-16-278 Nonbank Servicers

that the financial crisis was associated with significant increases in

delinquencies, mortgage defaults, and foreclosures.

24

Some market participants we interviewed cited several reasons why the

growth in the share of mortgages serviced by nonbank servicers might

slow in the future. For example, they cited declining delinquency rates

and increased regulatory scrutiny of MSR transfers that could reduce the

number and size of MSR transfers from bank to nonbank servicers.

Others we interviewed also said they generally expect banks to service

more mortgages in the future as the housing market continues to

stabilize. For example, FHFA officials explained that they expect banks to

increase their performing loan servicing in the future due to improved

economic conditions and better quality loans originated since the 2007-

2009 financial crisis. Likewise, Fannie Mae representatives also said they

expect some banks to begin servicing more loans, particularly performing

loans.

25

Similarly, representatives from two market research firms said

that regional and midsized banks are showing renewed interest in buying

MSR. Conversely, small and midsized nonbank servicers we interviewed

said they did not expect banks to increase servicing given rising servicing

costs associated with various new regulations, including those issued by

CFPB, and Basel III capital standards, which make owning MSR more

expensive for banks.

26

While nonbank servicers are non-deposit-taking institutions with a specific

focus on servicing mortgage loans, these entities vary across a number of

different characteristics, including revenue sources, funding sources,

costs, and their area of specialization. Some examples of the diverse

range of institutions in the mortgage servicing industry include the

following:

• small servicer-only companies, some of which specialize in specific

functions such as servicing or sub-servicing delinquent loans;

• full-service mortgage finance companies that also originate loans;

24

GAO, Financial Regulatory Reform: Financial Crisis Losses and Potential Impacts of the

Dodd-Frank Act, GAO-13-180 (Washington, D.C.: Jan. 16, 2013).

25

We consider performing loans to be loans that are not delinquent.

26

For a more complete discussion of Basel III, see GAO-15-67.

Characteristics of

Nonbank Servicers Vary

Page 17 GAO-16-278 Nonbank Servicers

• entities owned by investors such as real estate investment trusts,

hedge funds or private equity funds;

• subsidiaries or affiliates of large nonbanks, including financial and

nonfinancial firms;

• companies that acquire MSR and use sub-servicer arrangements to

service the loans; and

• publicly traded companies.

Appendix III provides a list of nonbank servicers we identified in the

course of our audit work.

We found that nonbank servicers’ largest source of revenue is typically

servicing fees, but their sources of revenue vary. Nonbank servicers

generally collect monthly fees based on a percentage of the remaining

unpaid principal balance on each loan serviced, although some nonbank

servicers, including three we interviewed, may instead receive a flat fee

per loan when sub-servicing for others. Representatives from several

nonbank servicers we interviewed also discussed relying on other

sources of revenue, including ancillary fees and float income.

27

Nonbank

servicers with more diversified operations can also earn revenue from a

range of other activities, including loan origination, investment, and

consulting.

Likewise, we found that nonbank servicers’ funding sources can vary.

Nonbank servicers we interviewed said they use equity, debt, and lines of

credit to help fund their operations. For example, some nonbank servicers

are publicly traded and can use equity to fund their operations. In

addition, nonbank servicers can fund their operations by securing lines of

credit, issuing bonds, or undertaking a number of other capital and

liquidity-raising alternatives. The majority of the 10 nonbank servicers we

27

Ancillary fees are fees imposed on borrowers for events such as late payment or

bounced checks. Servicers earn float income by investing principal and interest payments

they receive from borrowers for a short period before remitting them to the loan holder.

For example, borrowers might make their payment on the first of the month, but the

servicer does not remit these payments to the loan holder until the 25th of the month. In

the interim, the servicer may place the payments in investment-grade assets and keep the

investment income for itself.

Revenue, Funding Sources,

and Costs

Page 18 GAO-16-278 Nonbank Servicers

interviewed said they also use lines of credit to fund various operations,

including mortgage originations and MSR purchases, and to advance

principal and interest payments to investors in cases where borrowers fail

to make monthly payments.

28

Regulators and other market participants

agreed that nonbank servicers can experience higher funding costs

compared to bank servicers. They said that unlike bank servicers,

nonbank servicers do not have access to customer deposits, which are a

cheaper source of funding than other capital and money market

alternatives.

Representatives from most of the nonbank servicers we interviewed also

largely agreed that personnel costs are their main expense, although

costs can vary based on a servicer’s business model and size. As we

discuss later, some nonbank servicers specialize in delinquent loans and

therefore may experience higher employee costs related to servicing

those loans. For instance, the Urban Institute reported that delinquent

loans are typically more difficult and costly to service because such loans

require more labor-intensive, direct interactions with borrowers to ensure

that they are offered appropriate options to remain in their homes.

29

A

number of servicers we interviewed also said that technology can be a

large cost. To the extent that some technology costs are fixed, these

would disproportionally affect smaller servicers. Similarly, smaller

nonbanks may be disproportionately affected by regulatory compliance

costs, such as those associated with new servicer guidelines and

enhanced scrutiny of the foreclosure process.

A number of nonbank servicers specialize in servicing delinquent loans,

according to various market participants, but others do not. For example,

representatives from two nonbank servicers said that they were able to

expand their businesses during the 2007-2009 financial crisis by

specializing in delinquent loans as delinquency rates rose to historic

levels. As a result of nonbank servicers’ willingness to service delinquent

loans, larger portions of the loans they service tend to be delinquent

relative to the loans serviced by their banking counterparts. For example,

28

In some cases, such as for Ginnie Mae-guaranteed MBS and some enterprise-issued

MBS and enterprise-owned loans, servicers are required to remit scheduled principal and

interest payments even if borrowers fail to make their monthly mortgage payments. These

are often referred to as advance payments.

29

Pamela Lee, Nonbank Specialty Services: What’s the Big Deal? Urban Institute

(Washington, D.C.: Aug. 2, 2014).

Specialization

Page 19 GAO-16-278 Nonbank Servicers

the average number of delinquent loans—as a percentage of loans

serviced—in Ginnie Mae and enterprise MBS and enterprise-owned

portfolios was higher for nonbank than bank servicers as of the second

quarter of 2015.

30

Specifically, for the enterprises, the delinquency rate for

loans serviced by nonbank servicers was .84 percentage points higher on

average than those serviced by bank servicers.

31

Similarly, the average

delinquency rate for loans serviced by nonbank servicers for Ginnie Mae

was 1.4 percentage points higher than those serviced by bank

servicers.

32

For nonbank servicers of Ginnie Mae MBS, the specialization

in delinquent loans is a continuation of a multiyear pattern. Specifically,

Ginnie Mae data show that for each year from the fourth quarter of 2007

through the second quarter of 2015, nonbank servicers of Ginnie Mae

MBS have had higher average delinquency rates than bank servicers.

However, representatives from other nonbank servicers and market

participants we interviewed said that many nonbank servicers do not

consider themselves specialty servicers nor do they actively seek to

service delinquent loans. Moreover, while delinquent loans are a common

area of specialization for nonbank servicers, others focus on specific loan

products or geographic locations where they have developed expertise

and, on the basis of the specialization, may provide support to larger bank

and nonbank servicers.

30

For the purposes of this analysis, delinquent loans were loans that were 90 days or

more past due or in foreclosure for Ginnie Mae and Freddie Mac, and 3 months or more

past due or in foreclosure for Fannie Mae.

31

For this analysis, delinquent loans were loans that were 90 days or more past due or in

foreclosure for Ginnie Mae and Freddie Mac, and 3 months or more past due or in

foreclosure for Fannie Mae. Average delinquency rates for bank and nonbank servicers

are calculated by averaging the delinquency rates—by number of loans serviced—of each

servicer in each servicer category. Ginnie Mae and Fannie Mae provided us with the

delinquency rates of their bank and nonbank servicers. We calculated the delinquency

rates for Freddie Mac bank and nonbank servicers using servicer-level data provided to us

by Freddie Mac. We defined banks as bank holding companies, financial holding

companies, savings and loan holding companies, insured depository institutions, and

credit unions, including any subsidiaries or affiliates of these types of institutions.

32

Ginnie Mae officials noted that nonbank servicers’ higher delinquency rates may be only

partially due to their specialization. Higher delinquency rates may also reflect nonbank

servicers’ unwillingness or inability to purchase delinquent loans out of Ginnie Mae-

guaranteed loan pools. According to Ginnie Mae officials, banks often do this with Ginnie

Mae-guaranteed MBS, which has the effect of lowering the delinquency rates for their

servicing portfolio.

Page 20 GAO-16-278 Nonbank Servicers

The growth of nonbank servicer participation in the mortgage servicing

industry since the financial crisis has produced some benefits for

consumers and other market participants. While the extent of the benefits

varies according to the individual servicer and is not necessarily due to

differences between banks and nonbanks, many market participants said

that the growth of nonbank servicers has increased the capacity for

servicing delinquent loans and that their expertise may have also

produced additional benefits for some borrowers. Evidence also suggests

that the growth of nonbanks has helped increase liquidity in the market for

MSR, which supports mortgage markets more generally.

Increased Capacity for Delinquent Loan Servicing. The increased

participation of nonbank servicers capable of servicing delinquent loans

may have contributed to improved outcomes for some of these loans

since the financial crisis. Market participants we interviewed noted that in

the years after the 2007-2009 financial crisis, existing bank servicers

lacked the capacity and capability to effectively service the large volume

of delinquent loans that emerged. Moreover, some servicers were unable

to effectively handle the higher level of interaction with borrowers required

by delinquent loans. As a result, the mortgage servicing industry

experienced poorly designed loan modification systems as well as errors

and deficiencies in foreclosure processing. For example, in 2011 and

2012, in response to critical weaknesses in bank servicers’ foreclosure

activities, federal banking regulators issued formal consent orders against

16 bank servicers to ensure safe and sound mortgage servicing; address

weaknesses identified in foreclosure reviews; and remediate harm to

Nonbank Servicer

Growth Poses Both

Benefits and

Challenges for Market

Participants and

Consumers

Nonbank Servicer Growth

Has Improved Servicing

Capacity for Delinquent

Loans and Increased

Liquidity

Page 21 GAO-16-278 Nonbank Servicers

borrowers.

33

A 2014 study by the Urban Institute noted that this capacity

and capability gap was addressed, in part, by the increased participation

of nonbank specialty servicers whose servicing platforms were more

effective in handling distressed loans. As a result, some nonbank

servicers may have contributed to improved consumer outcomes for

some delinquent loans. For example, a 2014 study on loan modifications

noted that borrowers benefited from reduced payments, interest rates,

and loan balances offered by nonbank servicers, which could potentially

reduce the likelihood of foreclosure.

34

However, their empirical evidence

on the relative performance of nonbanks in servicing delinquent loan is

not definitive. For instance, one study we reviewed found that borrowers

in delinquency were more likely to experience positive outcomes when

their servicer was a nonbank, including the borrower making a payment

on a loan that had been in default, receiving offers of modifications with

principal decreases, and receiving offers for second modifications. Over

time, however, the study found that banks have increased their propensity

to offer interest rate modifications and greater payment reductions.

However, this study was based on privately securitized nonprime loans

and therefore cannot speak to outcomes for delinquent prime loans or

loans outside of private-label securities. The study also contains a

number of other limitations that require caution in the interpretation of the

33

In addition, in February 2012, the Departments of Justice, Treasury, and Housing and

Urban Development and state banking regulators along with 49 state attorneys general,

reached a settlement with the country’s largest mortgage servicers. See United States v.

Bank of America Corp., No. 1:12-cv-00361 (D.D.C. Apr. 4, 2012). This agreement, known

as the National Mortgage Settlement, provided approximately $25 billion in relief to

distressed borrowers in states that signed onto the settlement and directed payments to

participating states and the federal government.

34

Carolina K. Reid, Michael J. Collins, and Carly Urban, “Servicer Heterogeneity: Does

Servicing Matter for Loan Cure Rates?” University of California, Berkeley: Fisher Center

for Real Estate and Urban Economics Working Paper Series (2014). The study controlled

for borrower, loan, and market characteristics and investigated the difference in outcomes

for borrowers with delinquent subprime mortgages in private-label securities whose

servicers were banks and nonbank servicers.

Page 22 GAO-16-278 Nonbank Servicers

results.

35

Moreover, representatives from consumer groups we spoke with

said that they did not notice a difference in servicing quality between bank

and nonbank servicers for borrowers with delinquent loans, and they said

that outcomes depended on the expertise and quality of the individual

company.

Increased Liquidity. Nonbank servicers have contributed to liquidity in

the secondary mortgage market since the financial crisis by broadening

participation in the market for MSR, which benefits banks and other

originators looking to sell mortgage assets. Additional participants in the

market for MSR generally contribute to a more liquid market, where large

MSR transactions can be executed with relative ease and at low costs. A

liquid market for MSR benefits buyers and sellers of MSR directly by

providing a mechanism to transact effectively in MSR and raise liquidity. It

also indirectly facilitates sales of whole loans to investors that do not want

the associated servicing responsibilities or that want the option to sell the

servicing rights in the future.

36

Moreover, the entry of new, diverse groups

of investors, such as hedge funds, real estate investment trusts, and

specialty servicers, has generated increased liquidity in MSR associated

with a wide variety of loan products. For example, some nonbank

servicers specialize in acquiring MSR related to nonprime mortgage loans

originated prior to 2008 or, as discussed previously, delinquent loans that

are more demanding to service. Such institutions were instrumental in

enhancing the ability of the market to absorb the supply of MSR that

resulted from banks’ desire to decrease the volume of nonprime and

35

For example, the study does not include a significant segment of the market—prime and

portfolio loans—that is largely serviced by banks. The data used for the study are based

on privately securitized subprime and Alt-A loans. Thus, there is a potential selection bias

in that the sample used could be dominated by nonbank servicers. The authors do not

provide any summary statistics on the share of nonbank servicers compared to bank

servicers in the sample. Furthermore, the authors indicate they identified nonbank

servicers through news articles in trade publications, which may create additional issues

with the sample used to conduct the empirical analysis. Moreover, since the results are

based on a convenience sample, they cannot be used to draw inferences about all Alt-A

loans.

36

The ability of originators to sell loans into secondary markets generates funds to support

additional loan origination. A liquid market for MSR facilities this process, as some

investors seeking to purchase mortgages do not have servicing platforms or are otherwise

uninterested in servicing rights. These entities therefore rely on a liquid market for selling

the MSR associated with the loan or will purchase only the loan from originators, leaving

the MSR for another entity. As a result, nonbanks servicers, by supporting secondary

mortgage market activity, ultimately benefit consumers.

Page 23 GAO-16-278 Nonbank Servicers

distressed loans in their servicing portfolios, likely improving the liquidity

of the market. Further, diversity in the types of servicers in the market

produces competition between entities with varying levels of expertise

and tolerance for risk. This competition can result in more efficient pricing

in the market for MSR, specifically MSR markets for delinquent loans and

unconventional loans. Ginnie Mae’s 2014 report noted that the rising

prominence of nonbank servicers enhanced market liquidity by offsetting

the decreased participation of bank servicers.

37

The increased participation of nonbank servicers in mortgage servicing

has created benefits but also poses risks to consumers, the enterprises,

Ginnie Mae, and others. For example, some challenges are related to the

business models and operational systems of particular nonbank

servicers, such as those stemming from certain nonbanks’ heightened

vulnerability to MSR price movements. Other challenges are related to

the transfers of MSR that occur among banks and nonbanks servicers,

which can result in violations of consumer protection laws and other

regulations. Because there is considerable variation in the types of

servicers in the market, it is important to note that in many cases the risks

to market participants vary by individual servicer as opposed to whether

the servicer is a bank or nonbank. Nevertheless, a number of challenges

exist, some of which are specific to certain types of nonbanks and some

of which are more general servicer challenges that have been heightened

by nonbank growth.

Several market participants and one state regulator we spoke with said

that operational challenges at some nonbanks were caused by overly

rapid growth, particularly after the financial crisis, which strained some

nonbank servicers’ operational capabilities and finances. Concerns have

been raised by the FHFA Office of Inspector General and others that

recent growth at some specialty servicers could result in servicing issues

for customers, including where support infrastructure may not have

adequately kept pace with expanding portfolios.

38

In particular, some

market participants told us that some nonbank servicers may be more

37

Ginnie Mae, An Era of Transformation (September 2014).

38

See Federal Housing Finance Agency (FHFA), Office of Inspector General, FHFA

Actions to Manage Enterprise Risks from Nonbank Servicers Specializing in Troubled

Mortgages, AUD-2014-014 (Washington, D.C.: July 1, 2014).

Growth of Nonbanks

Presents Some Risks to

Consumers and Other

Market Participants

Rapid Growth and Immature

Operational Systems

Page 24 GAO-16-278 Nonbank Servicers

susceptible to difficulties due to less mature infrastructures relative to

banks for tasks such as managing regulatory compliance, risks, and

internal controls. Weak internal controls and compliance programs can

result in harm to consumers, such as problems or errors with account

transfers, payment processing, and loss mitigation processing. Ginnie

Mae officials said that newer nonbank servicers, which are often created

and financed by private investors and seek to acquire significant portfolios

of servicing rights, may underestimate the operational requirements

involved in servicing large portfolios, such as answering high volumes of

customer-service inquiries or reaching out to many borrowers with

delinquent loans. Servicers acquiring MSR may encounter a number of

issues that require effective systems and knowledge of the state and

federal laws and requirements as they relate to servicing mortgages,

which may challenge the expertise of newer servicers. Smaller nonbank

servicers may also face difficulties related to their ability to manage

operational challenges, although this challenge may be due to the size of

the entity and may not be unique to nonbank servicers.

Issues related to aggressive growth and insufficient infrastructure have

resulted in harm to consumers, have exposed counterparties to

operational and reputational risks and, as we discuss later in this report,

complicated servicing transfers between institutions. We examined

servicer reviews by the enterprises and identified differences in the

degree of operational issues experienced by bank and nonbank

servicers.

39

Specifically, the enterprises on average found more issues

considered high-risk at nonbanks—such as insufficient monitoring of loan

accounts—than at banks. Moreover, both enterprises gave more “needs

improvement” or “unsatisfactory” assessments to reviewed nonbank

servicers compared to banks. In addition, CFPB’s examinations found

servicing problems at nonbanks due to a lack of robust compliance

39

Each enterprise reviewed these entities using its own set of review criteria. In this report,

we do not attempt to assess the appropriateness of these criteria. Each enterprise’s

examinations identified individual findings and categorized them based on their riskiness,

as well as determining overall assessments of servicer performance (e.g., unsatisfactory;

needs improvement; satisfactory). One enterprise assigned an overall assessment to the

servicer, while the other assessed different areas of servicer performance. While each

enterprise used different language in its assessment of servicers, for the purposes of

comparison we have normalized the language here.

Page 25 GAO-16-278 Nonbank Servicers

systems.

40

However, a credit rating agency and one servicer we spoke

with said that nonbank servicers had improved their operational systems

over time.

While issues with transfers of MSR are not unique to nonbanks, their

incidence has increased since the financial crisis, in part due to

increasing numbers of servicing transfers involving nonbanks and

potentially exacerbated by the immature operational systems for specific

servicers. Ineffective transfers can have negative consequences for

investors and borrowers. The transfer process is complex and requires

management and communication by both parties to the transfer. Among

other requirements during the transfer process, the servicers transferring

MSR must provide the servicers receiving them with borrowers’ complete

documentation. The new servicer also must abide by agreements (either

established or in progress) between the borrower and the previous

servicer. In addition, both parties must communicate with borrowers to

help ensure that they understand the status of their loan and have timely

and accurate information regarding loss mitigation procedures. Issues

can emerge for borrowers when either servicer fails to fulfill these

requirements, and when other issues—such as incompatible

technological systems—produce errors. For example, CFPB has

observed that if the transfer process is not handled properly, consumers

may find that their servicer could miss documentation or that the servicer

did not credit payments on time.

41

As nonbanks engaged in significant acquisitions of MSR from other

servicers during and after the financial crisis, a combination of errors and

improper actions on the part of both transferring and receiving servicers

led to borrowers experiencing harm, including losing their homes to

foreclosure in some cases. While some servicers have increased their

ability to properly manage these complex transactions, variability in

servicer quality across nonbanks receiving the transfers remains an area

40

In the fall 2015 issue of the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau’s (CFPB) publication

that provides the public and the financial industry with a summary of any unfair, deceptive,

abusive acts or practices, CFPB summarized its examination findings for both bank and

nonbank servicers. See CFPB, Supervisory Highlights, Issue 9, Fall 2015 (Washington,

D.C.: Nov. 3, 2015).

41

Effective January 2014, CFPB established new mortgage servicing rules that included

rules obligating bank and nonbank servicers to maintain certain policies and procedures

regarding the transfer of loans. 12 C.F.R. § 1024.38.

Mortgage Servicing Transfer

Issues

Page 26 GAO-16-278 Nonbank Servicers

of focus for regulators, as discussed later. According to regulators,

transfer errors or other issues can be especially harmful for borrowers in

loss mitigation proceedings, whereby a borrower may apply for payment

relief or request new terms for his or her loan. For example, CSBS

officials said that in MSR transfers that resulted from servicers’ failure,

some borrowers lost contact with their servicers, and their new servicers

did not always receive or adhere to borrowers’ existing loss mitigation

agreements with the previous servicer. In some cases, these types of

transfer errors may have resulted in some borrowers improperly losing

their homes to foreclosure.

While nonbank servicers employ a range of business characteristics,

some nonbanks are more susceptible to risks that can lead to operational

problems and ultimately broader effects, including effects on investors,

consumers and other servicers. For example, liquidity challenges are

more pronounced for nonbanks, as many face expensive alternatives for

external financing and do not have access to consumer deposits, which

can be a cheaper and more reliable source of funding. In particular, many

nonbank servicers rely on short-term credit facilities, such as lines of

credit and advances with borrowing limits. In some cases, nonbank

servicers depend on a single investor or a few creditors and are therefore

particularly vulnerable to a withdrawal of funds. In addition, some

servicers must sometimes advance principal and interest on delinquent

loans to investors without the revenue generated by the underlying loan.

Various market participants we spoke with indicated that some nonbank

servicers might face funding liquidity risks, in part due to market volatility

because of several features of their business models and expensive

external funding alternatives.

42

However, some nonbank servicers have

better access to liquidity to support their operations, including publicly

traded entities or those affiliated with larger entities with significant access

to capital markets.

Some servicers, including specialty servicers, have business models that

result in significant concentrations of MSR on their balance sheets

relative to capitalization and servicing income as their principal source of

42

Funding liquidity risk is the risk that a firm will not be able to meet its current and future

cash flow and collateral needs, both expected and unexpected, without materially affecting

its daily operations or overall financial condition.

Liquidity Risk and MSR

Volatility

Page 27 GAO-16-278 Nonbank Servicers

revenue.

43

As a result, while all MSR holders are sensitive to changes in

MSR values, due to a lack of diversification, some nonbanks are

particularly vulnerable to these fluctuations. MSR values are highly

volatile, as they depend on interest rates and loan mortgage defaults.

44

For example, a large nonbank servicer reported in its third quarter 2015

earnings press release that its servicing revenue had declined by 67

percent, in part driven by a 285 percent decline in the market value of its

MSR assets compared to the previous quarter. These fluctuations can

affect perceptions of the financial condition of institutions and therefore

the willingness of creditors to provide them with the liquidity required for

critical operations. Some nonbanks have more diversified operations to

mitigate the risks associated with MSR volatility, such as those that

originate loans. In addition, our analysis of some nonbank servicers’

financial reports revealed their attempts to hedge risk associated with

MSR, including one servicer that has engaged in transactions designed to

transfer interest rate risk to capital markets.

45

Another way to mitigate the

risk of significant MSR concentrations is to hold sufficient capital to

absorb potential losses associated with changes in MSR valuations.

46

Issues at nonbanks related to liquidity challenges and MSR volatility can