CC2017 Poster Competition • The history of the scalpel: From flint to zirconium-coated steel •

13

© 2017 by the American College of Surgeons. All rights reserved.

10987654321

AUTHORS

Jason B. Brill, MD

Evan K. Harrison, MD

Michael J. Sise, MD, FACS

Romeo C. Ignacio, Jr., MD, FACS

CORRESPONDING AUTHOR

Jason B. Brill, MD

Residency in General Surgery

Naval Medical Center

San Diego, CA

2

The history of the scalpel:

From flint to zirconium-coated steel

CC2017 Poster Competition • The history of the scalpel: From flint to zirconium-coated steel •

14

© 2017 by the American College of Surgeons. All rights reserved.

10987654321

The surgical knife, one of the earliest surgical

instruments, has evolved over 10 millennia.

While the word “scalpel” derives from the Latin

word “scallpellus,” the physical instruments

surgeons use today started out as flint and

obsidian cutting implements during the Stone

Age. As surgery developed into a profession,

knives dedicated to specific uses also evolved.

Barber-surgeons embellished their scalpels

as part of the art of their craft. Later, surgeons

prized speed and sharpness. Today’s advances

in scalpel technology include additional safety

measures and gemstone and polymer coatings.

The quintessential instrument of surgeons,

the scalpel is the longstanding symbol of the

discipline. Tracing the history of this tool reflects

the evolution of surgery as a culture and as a

profession.

Origins

Pinpointing a specific period of time when a cutting implement

became the first surgical knife depends largely on perspective.

Shells, razor-like leaves, bamboo shoots, and even fingernails

may all be viewed as early surgical instruments. Thumbnails

for newborn circumcisions, scarification via plant stems, and

venesection with sharks’ teeth served as the first examples

of sharp tools for procedures on the human body.

1,2

John

Kirkup, MB, BS—a retired surgeon and honorary curator of

the Historical Instruments Collection at the Royal College of

Surgeons of England—researched the history of surgical tools

for more than 20 years.

3

According to Dr. Kirkup, circumcision

with sharpened stones, one of the earliest recorded elective

procedures, evolved into knives used for basic procedures.

4

Excavations of archaeological sites dating to the Paleolithic

and Neolithic periods revealed knives for surgical use as early

as 10,000–8,000 BC.

5

Blades were initially composed of flint,

jade, and obsidian, with specific pieces chosen for their sharp

edges. Fracture and flake techniques were then employed to

refine these early blades into cutting instruments with desired

characteristics, making these objects among the first human-

refined tools.

6

A particularly well-preserved prehistoric blade mounted onto

a handle was found in 1991, preserved in ice near the Austrian-

Italian border (see Figure 1). These types of tools were used

for scarification, venesection, lancing, and circumcision. In

fact, these instruments were still used for many of the same

purposes by Alaska Native tribes well into the 19th century.

7

Evidence of obsidian blades used for more complex procedures

such as craniotomies appeared around 4000 BC in prehistoric

Anatolia, modern-day Turkey. Some archeological specimens

are still sharp enough to incise skin.

8

1

CC2017 Poster Competition • The history of the scalpel: From flint to zirconium-coated steel •

15

© 2017 by the American College of Surgeons. All rights reserved.

10987654321

Transition to modern scalpels

Metal blades replaced sharpened stone: first it was copper

(3500 BC), followed by bronze and then iron (1400 BC). But

it wasn’t until 400 BC that the concept of a surgical knife was

first described by Hippocrates.

9

He used the term “macairion,” a

smaller version of a Lacedaemonian sword called a “machaira,”

to describe the surgical tool. The machaira was a broad-

cutting blade with a single edge and sharp point, containing

the same essential features of the modern scalpel as defined

by Stedman’s Medical Dictionary: “A pointed knife with a

convex edge.”

10,11

In Rome, Galen and Celsus used an instrument

with this shape—a small, sharp blade for specialized used for

incision and drainage, tendon repairs, and vivisections (see

Figure 2).

The Romans named their version of this tool the “scallpellus,”

the diminutive form of the word scalper (“incisor” or “cutter”).

12

With the collapse of the Roman Empire, surgical innovation

flourished in the Islamic Golden Age. Albucasis (Abū al-Qāsim

Khalaf ibn al-‘Abbās al-Zahrāwī, 936–1013) in the Caliphate of

Córdoba (modern Spain) used a scalpel that held a retractable

blade.

13,14

Surgical instruments became even more varied and

specialized with the Renaissance in the 14th and 15th centuries.

Embellishments to the scalpel included fixed and folding blades

and specialized tips, such as lancets, bistouries, and double-

edged blades called catlins.

Barbers working during the Renaissance period, including

fathers of modern surgery such as Guy de Chauliac and

Ambroise Paré, used ornamented scalpels with artistic

flourishes that enjoyed wide popularity for several hundred

years.

15

The requirements of antisepsis and asepsis in the late

19th century subjected instruments to caustic chemicals and

pressurized steam sterilization, so nonmetallic decorations

became obsolete (see Figures 3 and 4).

4

3

2

CC2017 Poster Competition • The history of the scalpel: From flint to zirconium-coated steel •

16

© 2017 by the American College of Surgeons. All rights reserved.

10987654321

Disposable scalpels

King C. Gillette founded the American Safety Razor Company

(later the Gillette Safety Razor Company) in 1901 to produce

and market a handle-and-frame device that held disposable

razors. John Murphy, MD, FACS, a Chicago, IL, surgeon and one

of the founders of the ACS, adapted Gillette’s razors into a tool

that could be used when performing surgical operations. Dr.

Murphy’s version featured interchangeable blades, although it

required extra instruments to complete a blade exchange.

16

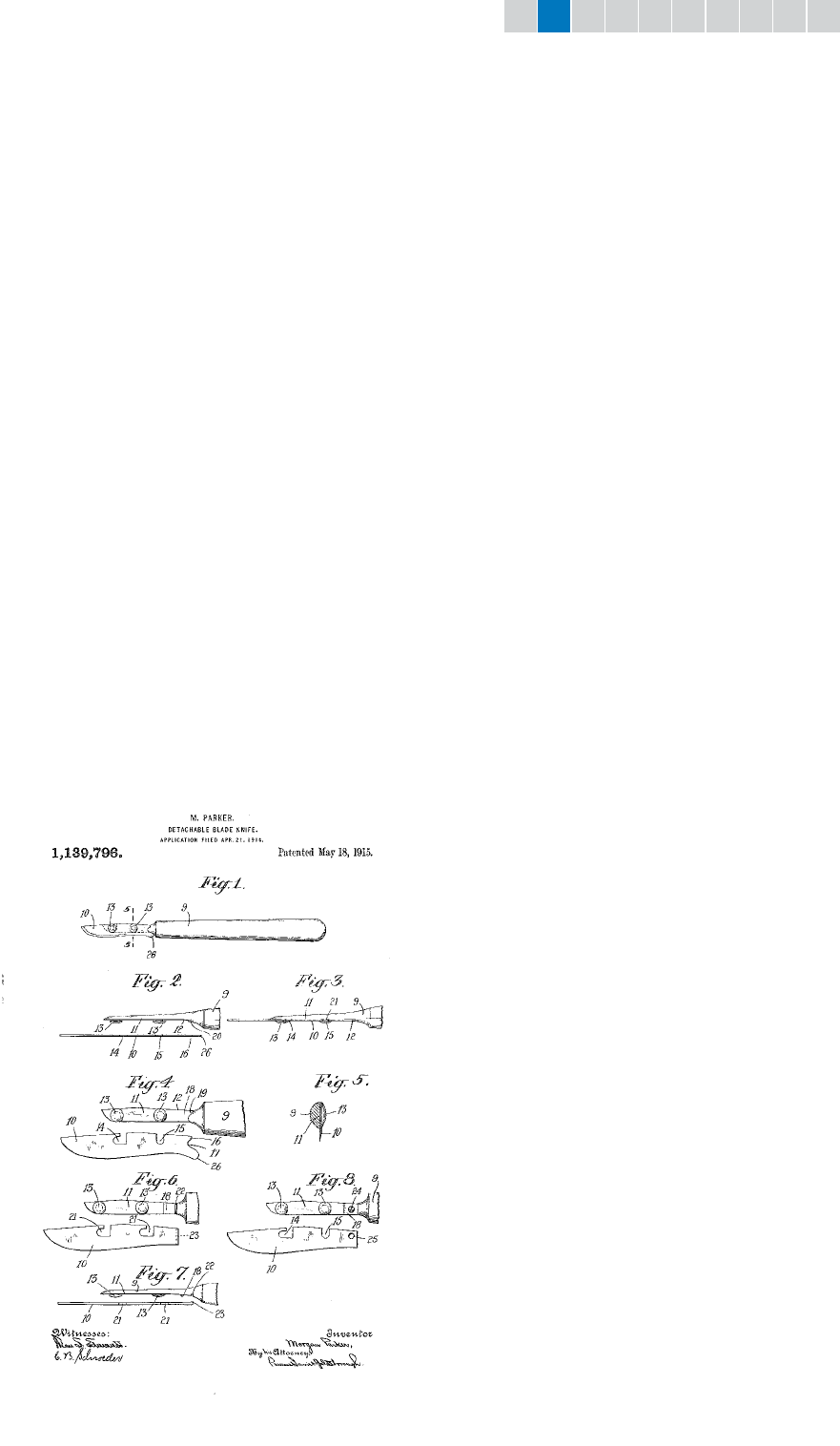

In 1914, Morgan Parker, a 22-year-old engineer, invented the

two-piece blade-and-handle medical scalpel that is used in ORs

today.

10

It allowed rapid mass-produced, sharp blades to be

used and exchanged on standard reusable handles. According

to legend, Mr. Parker’s uncle, a New York, NY, surgeon, became

impatient with the cumbersome process of the blade exchange

in his busy practice. A glance at Mr. Parker’s elegant solution

reveals its genius (see Figure 5). He stated the following in his

original patent application:

For the purpose of securing the blade to the handle, headed studs

are preferably provided on the handle adapted to co-act with

suitable slots in the blade. When such headed studs and slot are

employed, the blade may be readily secured upon the handle and

when in position will be held so rigidly as to preclude the possibility

of movement relative to the handle.

17

When Mr. Parker presented his scalpel at the ACS Clinical

Congress of 1915 in Boston, MA, its reception encouraged

him to take it to production. Mr. Parker, an engineer but

not a businessman, sought a partner. The first name listed

alphabetically in the phone book under “medical suppliers” was

C.R. Bard. Together, they formed the Bard-Parker Company,

which became one of the iconic names in surgery. They

developed cold sterilization to avoid superheating, which killed

microorganisms, but also dulled the blade. The rib-back handle

replaced those that bore the paired studs in 1936 in order to

ensure one-way fitment between the blade and handle.

The numbering system of blades and handles is arbitrary, a fact

that likely confirms the suspicions of generations of surgical

interns. As part of the Bard-Parker marketing scheme, each

new blade and handle design was given a new number and

occasionally a letter that denoted a “new and improved” model

(for example, #15C).

18

As a result, a given number has no

relation to size, shape, sharpness, or even a place in the product

timeline.

Modern additions

In the modern era, hardened alloys, such as 316L and 440C

stainless steel, replaced carbon steel in most settings.

Stainless steel had superior corrosion resistance, and reusable

handles benefited most from the high chromium content of

stainless steel. Retracting blades, a concept dating to the

time of Albucasis of the 10th century, became an increasingly

common safety feature. Nickel and chromium plating became

less common. Recent technological improvements include

zirconium nitride, diamond, and polymer coatings that

enhance the cutting edge. For all the improvements evident in

contemporary surgical technology, electron microscopic images

actually confirm that the edge of Neolithic obsidian blades

exceed today’s steel scalpels in sharpness.

19

Conclusion

The scalpel, since its first use as a medical knife by the Romans,

has been a symbol of the surgeon. Its evolution in many

ways mirrors the progress of those wielding it. Prehistoric

humans used stone tools occasionally for medical uses. The

Greeks and Romans advanced both knowledge and skill while

creating dedicated surgical knives. The barber-surgeons

refined techniques as they refined the instruments used for

them. Asepsis mandated sweeping changes in both scalpel

and surgical practice. Today, the modern surgeon relies on

a wide array of technologically advanced and ever-changing

equipment, yet the operation still begins with the scalpel, the

profession’s oldest instrument.

5

CC2017 Poster Competition • The history of the scalpel: From flint to zirconium-coated steel •

17

© 2017 by the American College of Surgeons. All rights reserved.

10987654321

References

1 Scultetus J. The Chyrurgeon’s

Storehouse. London, UK:

Starker; 1674.

2 Pankhurst R. An historical

examination of traditional

Ethiopian medicine and

surgery. Ethiop Med J.

1964;3:157-167.

3 Kirkup J. The history

and evolution of surgical

instruments VI: The surgical

blade: From nger nail to

ultrasound. Ann R Coll Surg

Engl. 1995;77(5):380-388.

4 Jacobs MS. Circumcision. Ann

Med Hist. 1939;1(3):68-73.

5 Rezaian J, Forouzanfar F.

Consideration on trephinated

skull in the Sahre-e Sukte

(Burnt City) in Sistan. Res

Hist Med. 2012;1(4):157-168.

6 Moser L, Pedroti A. The

Neolithic settlement of

Lugo di Grezzana (Verona):

Preliminary report. In:

Belluzzo G, Salzani L, eds.

From Earth to Museum:

Exhibition of Prehistoric and

Protostorical Finds of the

Last Ten Years of Research

From the VeroneseTerritory.

Legnago, Italy: Fondazione

Foroni; 1996.

7 Ackerknecht EH.

Primitive surgery. Am

Anthropol.2009;49(1):25-45.

8 Shadbolt P. How Stone Age

blades are still cutting it

in modern surgery. CNN.

Available at: www.cnn.

com/2015/04/02/health/

surgery-scalpels-obsidian/

index.html. Accessed

November 10, 2017.

9 Adams F. The Genuine

Works of Hippocrates, Vol.

II. London, UK: Sydenham

Society; 1849.

10 Ochsner J. The surgical

knife. Bull Am Coll Surg

1999;84(2):27-37.

11 Stedman TL. Stedman’s

Medical Dictionary for the

Health Professions and

Nursing. Philadelphia, PA:

Lippincott Williams &

Wilkins; 2005.

12 Bliquez L. Tools of the empire.

In: The Tools of Asclepius:

Surgical Instruments in Greek

and Roman Times. Boston,

MA: Brill; 2015.

13 Elgohary MA. Al Zahrawi:

The father of modern surgery.

Ann Ped Surg. 2006;2(2):82-87.

14 Ahmadi SA, Zargaran A,

Mehdizadeh A, Mortazavi

SMJ. Remanufacturing and

evaluation of Al Zahrawi’s

surgical instruments, Al

Mokhdea as scalpel handle.

Galen Medical Journal

[online]. 2013;2(1):22-25.

Available at: www.gmj.

ir/index.php/gmj/article/

viewFile/42/27. Accessed

December 19, 2017.

15 Rutkow IM. On scalpels

and bistouries. Arch Surg.

2000;135(3):360.

16 Ochsner J. Surgical knife. Tex

Heart Inst J. 2009;36(5):441-

443.

17 Parker M. Detachable-

blade knife. U.S. Patent

US 1139796A. Available

at: http://pdfpiw.uspto.

gov/.piw?Docid=01139796.

Accessed December 19, 2017.

18 Arrow AK. Solving the

mystery of the scalpel

blades: What do the numbers

mean? Plast Reconstr Surg.

1996;97(4):861-862

19 Buck BA. Ancient technology

in contemporary surgery. West

J Med. 1982;136(3):265-269.

Legends

1 Flint dagger of Ötzi the Ice

Man. Image © South Tyrol

Museum of Archaeology/

Harald Wisthaler, Bolzano,

Italy.

2 Example of a Roman

scallpellus and similar

instruments. Courtesy of

Historical Collections &

Services, Claude Moore

Health Sciences Library,

University of Virginia,

Charlottesville.

3 Surgical set from the American

Revolutionary War. Displayed

in the Smithsonian National

Museum of American History,

the set includes wood and iron

handles and required routine

sharpening of the blades.

4 Detachable blades from

circa 1900. Courtesy of the

Royal College of Physicians

and Surgeons of Glasgow,

Scotland.

5 Morgan Parker’s original

patent. Source: United States

Patent and Trademark Ofce,

uspto.gov.