REPORTABLE

IN THE SUPREME COURT OF INDIA

CRIMINAL ORIGINAL/CIVIL APPELLATE JURISDICTION

WRIT PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 113 OF 2016

KAUSHAL KISHOR … PETITIONER(S)

VERSUS

STATE OF UTTAR PRADESH & ORS. …RESPONDENT(S)

WITH

SPECIAL LEAVE PETITION @ (DIARY) NO. 34629 OF 2017

J U D G M E N T

V. RAMASUBRAMANIAN, J.

PRELUDE

Said the Tamil Poet-Philosopher Tiruvalluvar of the Tamil Sangam

age (31, BCE) in his classic “Tirukkural”. Emphasizing the

importance of sweet speech, he said that the scar left behind by a

burn injury may heal, but not the one left behind by an offensive

1

Digitally signed by

Anita Malhotra

Date: 2023.01.03

16:58:23 IST

Reason:

Signature Not Verified

speech. The translation of this verse by G.U. Pope in English reads

thus:

“In flesh by fire inflamed, nature may thoroughly heal the sore;

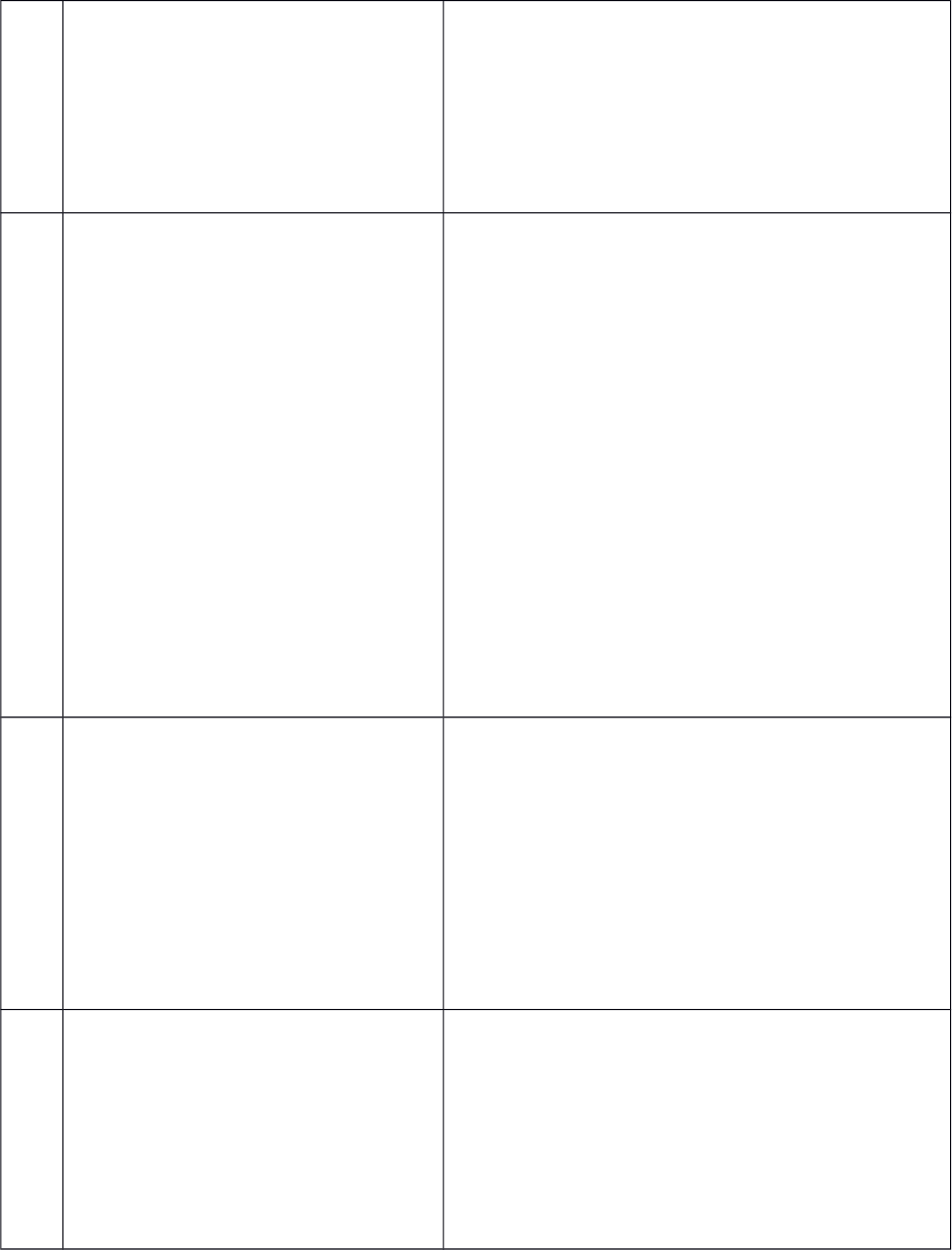

In soul by tongue inflamed, the ulcer healeth never more.”

A Sanskrit Text contains a piece of advice on what to speak and

how to speak.

! "# $ !$ %

! & ##

'

()* +$

,

- ##- .

satyam brūyāt priya brūyān na brūyāt satyam apriyamṃ |

priya ca nān ta brūyād e a dharma sanātanaṃ ṛ ṃ ṣ ḥ ḥ ||

The meaning of this verse is: “Speak what is true; speak what is

pleasing; Do not speak what is unpleasant, even if it is true;

And do not say what is pleasing, but untrue; this is the

eternal law.”

The “Book of Proverbs” (16:24) says:

“Pleasant words are a honeycomb, sweet to the soul and

healing to the bones”

Though religious texts of all faiths and ancient literature of all

languages and geographical locations are full of such moral

injunctions emphasising the importance of sweet speech (more than

2

free speech), history shows that humanity has consistently defied

those diktats. The present reference to the Constitution Bench is

the outcome of such behaviour by two honourable men, who

occupied the position of Ministers in two different States.

I. Questions formulated for consideration

1. By an order dated 05.10.2017, a Three Member Bench of this

Court directed Writ Petition (Criminal) No.113 of 2016 to be placed

before the Constitution Bench, after two learned senior counsel,

appointed as amicus curiae, submitted that the questions arising for

consideration in the writ petition were of great importance. Though

the Bench recorded, in its order dated 05.10.2017, the questions

that were submitted by the learned amicus curiae, the Three

Member Bench did not frame any particular question, but directed

the matter to be placed before the Constitution Bench.

2. At this juncture, a Special Leave Petition (Diary) No.34629 of

2017 arising out a judgment of the Kerala High Court came up

before the same Three Member Bench. Finding that the questions

raised in the said SLP were also similar, this Court passed an order

3

on 10.11.2017, directing the said SLP also to be tagged with Writ

Petition (Criminal) No.113 of 2016.

3. Thereafter, the Constitution Bench, by an order dated

24.10.2019, formulated the following five questions to be decided by

this Court:-

“…1) Are the grounds specified in Article 19(2) in

relation to which reasonable restrictions on the right

to free speech can be imposed by law, exhaustive, or

can restrictions on the right to free speech be imposed

on grounds not found in Article 19(2) by invoking other

fundamental rights?

2) Can a fundamental right under Article 19 or 21 of

the Constitution of India be claimed other than against

the ‘State’ or its instrumentalities?

3) Whether the State is under a duty to affirmatively

protect the rights of a citizen under Article 21 of the

Constitution of India even against a threat to the

liberty of a citizen by the acts or omissions of another

citizen or private agency?

4) Can a statement made by a Minister, traceable to

any affairs of State or for protecting the Government,

be attributed vicariously to the Government itself,

especially in view of the principle of Collective

Responsibility?

5) Whether a statement by a Minister, inconsistent

with the rights of a citizen under Part Three of the

Constitution, constitutes a violation of such

constitutional rights and is actionable as

‘Constitutional Tort”? …”

4

II. A brief backdrop

4. Without a brief reference to the factual matrix, the questions

to be answered by us may look abstract. Therefore, we shall now

refer to the background facts in both these cases.

5. Writ Petition (Criminal) No.113 of 2016 was filed under Article

32 of the Constitution praying for several reliefs including

monitoring the investigation of a criminal complaint in FIR

No.0838/2016 under Section 154 Cr.P.C., for the offences under

Sections 395, 397 and 376-D read with the relevant provisions of

the Protection of Children from Sexual Offences Act, 2012 (for

short, ‘POCSO Act’) and for the trial of the case outside the State

and also for registering a complaint against the then Minister for

Urban Development of the Government of U.P. for making

statements outrageous to the modesty of the victims. The case of

the petitioner in Writ Petition (Criminal) No.113 of 2016 in brief was

that on 29.7.2016 when he and the members of his family were

travelling from Noida to Shahjahanpur on National Highway 91 to

attend the death ceremony of a relative, they were waylaid by a

5

gang. According to the writ petitioner, the gang snatched away cash

and jewelry in the possession of the petitioner and his family

members and they also gang raped the wife and minor daughter of

the petitioner. Though an FIR was registered on 30.7.2016 for

various offences and newspapers and the television channels

reported this ghastly incident, the then Minister for Urban

Development of the Government of U.P. called for a press

conference and termed the incident as a political conspiracy.

Therefore, the petitioner apprehended that there may not be a fair

investigation. The petitioner claims that he was also offended by the

irresponsible statement made by the Minister and hence he was

compelled to file the said writ petition for the reliefs stated supra.

6. Insofar as Special Leave Petition (Diary) No.34629 of 2017 is

concerned, the same arose out of a judgment of the Division Bench

of the Kerala High Court dismissing two writ petitions. The writ

petitions were filed in public interest on the ground that the then

Minister for Electricity in the State of Kerala issued certain

statements in February 2016, 7.4.2017 and 22.4.2017. These

statements were highly derogatory of women. Though according to

6

the petitioners in the public interest litigation, the political party to

which the Minister belonged, issued a public censure, no action

was taken officially against the Minister. Therefore, the petitioner in

one writ petition prayed among other things for a direction to the

Chief Minister to frame a Code of Conduct for the Ministers who

have subscribed to the oath of office as prescribed by the

Constitution with a further direction to the Chief Minister to take

suitable action if any of the Ministers failed to live upto the oath.

The prayer in the second writ petition was for a direction to the

concerned Authorities to take action against the Minister for his

utterances.

7. Both the writ petitions were dismissed by a Division Bench of

the Kerala High Court, on the ground that the prayer of the public

interest writ petitioners were in the realm of moral values and that

the question whether the Chief Minister should frame a code of

conduct for the Ministers of his cabinet or not, is not within the

domain of the Court to decide. Therefore, challenging the said

common order, the petitioner in one of those public interest writ

petitions has come up with Special Leave Petition (Diary) No.34629

7

of 2017. Since the questions raised by the petitioner in the Special

Leave Petition overlapped with the questions raised in the Writ

Petition, they have been tagged together.

III. Contentions

8. We have heard Shri R. Venkataramani, learned Attorney

General for India, Ms. Aparajita Singh, learned senior counsel who

assisted us as amicus curiae, Shri Kaleeswaram Raj, learned

counsel for the petitioner in the special leave petition and Shri

Ranjith B. Marar, learned counsel appearing for the person who

sought to intervene/implead.

III.A. Preliminary note submitted by learned Attorney General

for India

9. The learned Attorney General for India submitted a

preliminary note containing his submissions question-wise, which

can be summed up as follows:-

Question No.1

(i) On question No.1 it is his submission that as a matter of

constitutional principle, any addition, alteration or change in

the norms or criteria for imposition of restrictions on any

fundamental right has to come up through a legislative

8

process. The restrictions already enumerated in clauses (2)

and (6) of Article 19 have to be taken to be exhaustive.

Therefore, the Court cannot, under the guise of invoking any

other fundamental right such as the one in Article 21, impose

restrictions not found in Article 19(2). Under the

Constitutional scheme, there can be no conflict between two

different fundamental rights or freedoms.

Question No. 2

(ii) The Constitution itself sets out the scheme of claims of

fundamental rights against the State or its instrumentalities

and it has also enacted in respect of breaches or violations of

fundamental rights by persons other than State or its

instrumentalities. Any proposition, to add or insert subjects or

matters in respect of which claims can be made against

persons other than the State, would amount to Constitutional

change. The concept of State action propounded and applied

in US Constitutional Law and the enactment of 42 US Code §

1983 have to be seen in the context of peculiar state of affairs

dealing with governmental and official immunities from legal

proceedings. In view of specific provisions in Articles 15(2), 17,

23 and 24 of the Indian Constitution, there may not be a strict

need to take recourse to the law obtaining in the USA. Claims

against persons other than the State, either through enacted

law or otherwise must be confined to constitutionally enacted

subjects or matters.

9

Question No. 3

(iii) There are sufficient Constitutional and legal remedies available

for a citizen whose liberty is threatened by any person. Beyond

the Constitutional and legal remedy and protection available,

there may not be any other additional duty to affirmatively

protect the right of a citizen under Article 21. Cases of

infringement of fundamental rights are taken care of under

Articles 32 and 226.

Question No. 4

(iv) Conduct of public servants like a Minister, if it is traceable to

the discharge of public duty or the duties of the office, is

subject to scrutiny of the law. Sanction for prosecution can be

granted if misconduct is committed under colour of office.

Such misconduct including statements that may be made by a

Minister cannot be linked to the principles of collective

responsibility. The concept of vicarious liability is incapable of

being applied to situations and no government can ever be

vicariously liable for malfeasance or misconduct of Minister

not traceable to statutory duty or statutory violations for the

purpose of legal remedies. Ministerial misdemeanors, which

have nothing to do with the discharge of public duty and not

traceable to the affairs of the State, will have to be treated as

acts of individual violation and individual wrong. To extend in

the abstract, the liability of the State to such situations or

instances without necessary limitations can be problematic.

10

Post M/s. Kasturi Lal Ralia Ram Jain vs. The State of

Uttar Pradesh

1

and following Rudul Sah vs. State of Bihar

2

,

this Court has treated misconduct of public servants or

officers and consequent infringement of Constitutional rights

as ground for grant of compensation. However, there is need

for clarity and certainty as far as the conceptual basis is

concerned. This may be better resorted through enacted law.

Question No. 5

(v) While the principle of Constitutional tort has been conceived

in Nilabati Behera (Smt.) alias Lalita Behera (Through the

Supreme Court Legal Aid Committee) vs. State of Orissa

3

,

and subsequently applied to provide in regard to the

constitutional remedies, the matter pre-eminently deserves a

proper legal framework in order that the principles and

procedures are coherently set out without leaving the matter

open-ended or vague.

III.B. Notes of submissions by Amicus

10. Ms. Aparajita Singh, learned senior counsel and amicus curiae

submitted a written note question-wise, which can be summed up

as follows:-

Question No. 1

1 AIR 1965 SC 1039

2 (1983) 4 SCC 141

3 (1993) 2 SCC 746

11

(i) The right to free speech under Article 19(1)(a) is subject to

clearly defined restrictions under Article 19(2). Therefore, any

law seeking to limit the right under Article 19(1)(a) has to

necessarily fall within the limitations provided under Article

19(2). Whenever two fundamental rights compete, the Court

will balance the two to allow the meaningful exercise of both.

This conundrum is not new, as the rights under Article 21 and

under Article 19(1)(a) have been interpreted and balanced on

numerous occasions. Take for instance the Right to

Information Act, 2005. The Act balances the citizen’s right to

know under Article 19(1)(a) with the right to fair investigation

and right to privacy under Article 21. This careful balancing

was explained by this Court in Thalappalam Service

Cooperative Bank Ltd. vs. State of Kerala

4

. The decision of

this Court in R. Rajagopal alias R.R. Gopal vs. State of

T.N.

5

is another example of reading down the restrictions (in

the form of defamation) on the right to free speech under

Article 19(2), in its application to public officials and public

figures in larger public interest. Again, in People’s Union for

Civil Liberties (PUCL) vs. Union of India

6

, the right to

privacy of the spouse of the candidate contesting the election

was declared as subordinate to the citizens’ right to know

under Article 19(1)(a). In Jumuna Prasad Mukhariya vs.

4 (2013) 16 SCC 82

5 (1994) 6 SCC 632

6 (2003) 4 SCC 399

12

Lachhi Ram

7

, a challenge to Sections 123(5) and 124(5) of the

Representation of the People Act, 1951 (as they prevailed at

that time) was rejected, on the ground that false personal

attacks against the contesting candidate was not violative of

the right to free speech. But when it comes to private citizens

who are not public functionaries, the right to privacy under

Article 21 was held to trump the right to know under Article

19(1)(a). This was in the case of Ram Jethmalani vs. Union

of India

8

, which concerned the right to privacy of account

holders. In Sahara India Real Estate Corporation Limited

vs. Securities and Exchange Board of India

9

, this Court

struck a balance between the right of the media under Article

19(1)(a) with the right to fair trial under Article 21. The

argument that free speech under Article 19(1)(a) was a higher

right than the right to reputation under Article 21 was rejected

by this Court in Subramanian Swamy vs. Union of India,

Ministry of Law

10

in which Section 499 IPC was under

challenge. The right to free speech was balanced with the right

to pollution free life in Noise Pollution (V.), in Re

11

and the

right to fair trial of the accused was balanced with the right to

fair trial of the victim in Asha Ranjan vs. State of Bihar

12

.

7(1955) 1 SCR 608

8(2011) 8 SCC 1

9(2012) 10 SCC 603

10(2016) 7 SCC 221

11(2005) 5 SCC 733

12(2017) 4 SCC 397

13

Question No. 2

(ii) There are some fundamental rights which are specifically

granted against non-State actors. Article 15(2)(a) – access to

shops, public restaurants, hotels and places of public

entertainment, Article 17 – untouchability, Article 23 – forced

labour and Article 24- prohibition of employment of children in

factories, mines etc., are rights which are enforceable against

private citizens also. Some aspects of Article 21 such as the

right to clean environment have been enforced against private

parties as well. The State is also under a Constitutional duty

to ensure that the rights of its citizens are not violated even by

non-State actors and ensure an environment where each right

can be exercised without fear of undue encroachment. In

People’s Union for Democratic Rights vs. Union of India

13

,

while rejecting the contention of the State that it was the

obligation of the private party i.e., the contractor to follow the

mandate of Article 24 of the Constitution and the relevant

laws, it was clarified that the primary obligation to protect

fundamental rights was that of the State even in the absence

of an effective legislation. In Bodhisattwa Gautam vs.

Subhra Chakraborty (Ms.)

14

, interim compensation was

awarded holding that fundamental rights under Article 21 can

be enforced even against private bodies and individuals. Public

law remedy has been repeatedly resorted to even against non-

13(1982) 3 SCC 235

14(1996) 1 SC 490

14

State actors when their acts have violated the fundamental

rights of other citizens. Award of damages against non-State

actors for violation of the right to clean environment under

Article 21 was laid down in M.C. Mehta vs. Kamal Nath

15

.

Similarly, the majority and concurring opinion in Justice K.S.

Puttaswamy vs. Union of India

16

, while elaborating on the

duty of the State and non-State actors to protect the rights of

citizens, pointed out that recognition and enforcement of

claims qua non-State actors may require legislative

intervention. However, when it comes to Article 19, a

Constitution Bench in P.D. Shamdasani vs. Central Bank of

India Ltd.

17

, has held it to be inapplicable against private

persons.

Question No. 3

(iii) Fundamental rights of citizens enshrined in the Constitution

are not only negative rights against the State but also

constitute a positive obligation on the State to protect those

rights. The Constitution Bench in State of West Bengal vs.

Committee for Protection of Democratic Rights, West

Bengal

18

, while upholding the power of the Constitutional

Court to transfer an investigation to the CBI without the

consent of the concerned State, emphasized the duty of the

15(2000) 6 SCC 213

16(2017) 10 SCC 1

171952 SCR 391

18(2010) 3 SCC 571

15

State to conduct a fair investigation which is a fundamental

right of the victim under Article 21. The majority judgment in

Justice K.S. Puttaswamy (supra), defines the positive

obligation of the State to ensure the meaningful exercise of the

right of privacy. In S. Rangarajan vs. P. Jagjivan Ram

19

, this

Court has categorically laid down that the State cannot plead

its inability to protect the fundamental rights of the citizens. In

Union of India vs. K.M. Shankarappa

20

, Section 6(1) of the

Cinematograph Act, 1952 which granted the Central

Government, the power to review the decision of the quasi-

judicial Tribunal under the Act, was sought to be defended on

the ground of law and order. The contention was rejected

holding that it was the duty of the Government to ensure law

and order. In Indibly Creative Private Limited vs.

Government of West Bengal

21

, the negative restraint and

positive obligation under Article 19(1) (a) has been explained.

In Pt. Parmanand Katara vs. Union of India

22

, it was held

that even the doctors in Government hospitals are duty bound

to fulfil the constitutional obligation of the State under Article

21.

Question No. 4

19(1989) 2 SCC 574

20(2001) 1 SCC 582

21(2020) 12 SCC 436

22(1989) 4 SCC 286

16

(iv) The Minister being a functionary of the State, represents the

State when acting in his official capacity. Therefore, any

violation of the fundamental rights of the citizens by the

Minister in his official capacity, would be attributable to the

State. The State also has a positive obligation to protect the

rights of citizens under Article 21, whether the violation is by

its own functionaries or a private person. It would be

preposterous to suggest that while the State is under an

obligation to restrict a private citizen from violating the

fundamental rights of other citizens, its own Minister can do

so with impunity. However, the factum of violation would need

to be established on the facts of a given case. It would involve

a detailed inquiry into questions such as (a) whether the

statement by the Minister was made in his personal or official

capacity; (b) whether the statement was made on a public or

private issue; (c) whether the statement was made on a public

or private platform. In Amish Devgan vs. Union of India

23

,

while dealing with hate speech, the impact of the speech of “a

person of influence” such as a Government functionary, was

explained. State of Maharashtra vs. Sarangdharsingh

Shivdassingh Chavan

24

, provides a clear instance of direct

interference with the investigation by a Chief Minister. The

Court held the action of the Chief Minister to be "wholly

unconstitutional" and contrary to the oath of allegiance to the

Constitution and imposed costs on the State. The concurring

opinion emphasizes the responsibility that the oath of office

casts on the Minister under the Constitution. In Secretary,

Jaipur Development Authority, Jaipur vs. Daulat Mal

23(2021) 1 SCC 1

24(2011) 1 SCC 577

17

Jain

25

, while dealing with a case involving the misuse of

public office by a Minister, this Court elaborated on the

responsibility and liability of the Ministerial office under the

Constitution. The importance of the Oath of Office under the

Constitution was also emphasized by the Constitution Bench

in Manoj Narula vs. Union of India

26

. However, the

Ministerial code of conduct was held to be not enforceable in a

court of law in R. Sai Bharathi vs. J. Jayalalitha

27

, as it

does not have any statutory force. An argument can be made

that the Minister is personally bound by the oath of his office

to bear true faith and allegiance to the Constitution of India

under Articles 75(4) and 164(3) of the Constitution. The

Constitution imposes a solemn obligation on the Minister as a

Constitutional functionary to protect the fundamental rights of

the citizens. The code of conduct for Ministers (Both for Union

and States) specifically lays down that the Code is in addition

to the “. . . observance of the provisions of the Constitution, the

Representation of the People Act, 1951”. Therefore, a

Constitutional functionary is duty bound to act in a manner

which is in consonance with this constitutional obligation of

the State.

Question No. 5

(v) The State acts through its functionaries. Therefore, the

official act of a Minister which violates the fundamental rights

of the citizens, would make the State liable under

constitutional tort. The principle of sovereign immunity of the

25(1997) 1 SCC 35

26(2014) 9 SCC 1

27(2004) 2 SCC 9

18

State for the tortious acts of its servant, has been held to be

inapplicable in the case of violation of fundamental rights.

The principle of State liability under Constitutional tort was

expounded in Nilabati Behera (supra). In Common Cause,

A Registered Society vs. Union of India.

28

, the position in

the case of a public functionary was explained.

III.C. Written submissions of Shri Kaleeswaram Raj, Advocate

for the SLP petitioner

11. Shri Kaleeswaram Raj, learned counsel appearing for the

petitioner in the special leave petition submitted an elaborate note.

This note is divided into several chapters dealing with the nature

and extent of the freedom of speech, the restrictions on the same,

the horizontality of fundamental rights, constitutional rights and

constitutional values, statements made by Ministers and collective

responsibility, self-regulation as the best mode of regulation, hate

speech not being a protected speech and the way forward. The

contents of this note are summarized as follows:-

(i) The Constitutional mandate of freedom of expression and

free speech is to be preserved without imposing

unconstitutional restrictions. It is a right available to

everyone including political personalities.

28(1999) 6 SCC 667

19

(ii) But even while upholding such a right, efforts should be

taken to frame a voluntary code of conduct for Ministers

etc., to ensure better accountability and transparency;

(iii) There is an imperative need to evolve a device such as

Ombudsman to act as a Constitutional check on the misuse

of the freedom of expression by public functionaries using

the apparatus of the State;

(iv) The right under Article 19(1)(a) is limited by restrictions

expressly indicated in Article 19(2), under which the

restrictions should be reasonable and must be provided for

by law, by the State. Therefore this Court cannot provide

for any additional restriction by an interpretative exercise or

otherwise;

(v) It is too remote to suggest that the right of a victim under

Article 21 stands violated if there is a statement by someone

that the case was born out of political conspiracy.

Therefore, there is actually no conflict of any other right

with Article 21;

(vi) Unlike Article 25 which makes the right thereunder subject

to public order, morality and health, Article 19(1)(a) does

not contain such restrictions. As held by this Court in

Sakal Papers (P) Ltd. vs. The Union of India

29

, freedom of

speech can be restricted only in the interest of security of

29(1962) 3 SCR 842

20

the State, friendly relations with foreign states, public order,

decency or morality or in relation to contempt of court,

defamation or incitement to an offence. It cannot be

curtailed, in the interest of the general public, as in the case

of freedom to carry on business;

(vii) Restricting speech by public figures, such as politicians, on

serious crimes will have great impact on the freedom of

speech. Such criticism which calls out true conspiracies

and true miscarriage of justice, plays an important role in a

democracy;

(viii) In so far as the enforcement of fundamental rights against

non-State actors is concerned, the vertical approach is

giving way to the concept of horizontal application. The

vertical approach connotes a situation where the

enforceability is only against the Government and not

against private actors. But with Nation States gradually

moving from laissez faire governance to welfare governance,

the role of the State is ever expanding, which justifies the

shift.

(ix) While the South African Constitution has adopted a

horizontal application by providing in Section 9(4) of the Bill

of Rights of Final Constitution of 1996 that no person may

unfairly discriminate directly or indirectly against anyone

on one or more grounds in terms of sub-Section (3) which

21

sets out the grounds that bind the State, the judiciary itself

has adopted a direct horizontal effect, in Ireland as could be

seen from the decisions in John Meskell vs. Córas

Iompair Éireann

30

and Murtagh Properties Limited vs.

Cleary

31

. In John Meskell (supra), the Irish Supreme Court

granted damages against the employer who dismissed the

employee for not joining a particular union after serving a

due notice to persuade him. In Murtagh Properties

Limited (supra), the High Court recognized and enforced

the right to earn livelihood without any discrimination

based on sex against a private employer. Countries like

Canada and Germany have developed indirect horizontal

application, meaning thereby that the rights regulate the

laws and statutes, which in turn regulate the conduct of

citizens;

(x) In the Indian context, direct horizontal effect has limited

application as can be seen from Articles 15(2), 17 and 24;

(xi) Paradigm cases of horizontality should be distinguished

from ordinary cases. For instance, the U.S. Supreme Court

held in Shelly vs. Kraemer

32

a covenant contained in a

contract prohibiting the sale of houses in a neighbourhood

to African-Americans, as unenforceable, for they have the

effect of denying equal protection under the laws. The

301973 IR 121

311972 IR 330

32334 U.S. 1 (1948)

22

Federal Constitutional Court of Germany took a similar view

in L thϋ

33

case (1958) where a call for boycott of a film

directed by a person who had worked on anti-semitic Nazi

propaganda was challenged. The German Court held that

there was an objective order of values that must affect all

spheres of law;

(xii) It has been repeatedly held by this Court that the power

under Article 226 is available not only against the

Government and its instrumentalities but also against “any

person or authority”. A reference may be made in this regard

to two decisions namely Praga Tools Corporation vs. Shri

C.A. Imanual

34

and Andi Mukta Sadguru Shree

Muktajee Vandas Swami Suvarna Jayanti Mahotasav

Smarak Trust vs.V.R. Rudani

35

;

(xiii) There are several instances where this Court has issued

writs under Article 32 against non-State actors. Broadly

those cases fall under two categories, namely, (i) private

players performing public duties/functions; and (ii) non-

State actors performing statutory activities that impact the

rights of citizens. Cases which fall under these two

categories have been held by this Court to be amenable to

writ jurisdiction as seen from several decisions including

33Luth (1958) BVerfGE 7, 198

34(1969) 1 SCC 585

35(1989) 2 SCC 691

23

M.C. Mehta vs. Union of India

36

. Absent any of these

parameters, the Court has refused to exercise writ

jurisdiction as seen from Binny Ltd. vs. V. Sadasivan.

37

;

(xiv) Even in jurisdictions where socio economic rights have

been elevated in status to that of constitutional rights, the

enforcement of those rights were made available only

against the State and not against private actors, as held by

this Court in Society for Unaided Private Schools of

Rajasthan vs. Union of India

38

;

(xv) On the issue of potential conflict of rights, it is important

to bear in mind the distinction between constitutional

rights and constitutional values. On a formal level, values

are understood teleologically as things to be promoted or

maximized. Rights, on the other hand, are not to be

promoted but rather to be respected. It would not show

proper concern for a right to allow the violation of one right

in order to prevent the violation of other rights. This would

promote the non-violation of rights, but it would not

respect rights

39

;

(xvi) Instead of values whose satisfaction is to be maximized,

rights act as constraints on the actions of the state. They

confer individuals with a sphere of liberty that is inviolable.

36 AIR 1987 SC 1086

37 (2005) 6 SCC 657

38 (2012) 6 SCC 1

39 Frances Kamm, Morality, Mortality Vol.2, Oxford University Press, 1996

24

Rights thereby act as restrictions on the government on

how to pursue values, including constitutional values. It is,

therefore, crucially important that we draw a distinction

between the constitutional rights and constitutional

values. Not every increase in liberty or every improvement

in leading a dignified life is a constitutional right. This

position has been accepted by this Court;

(xvii) As held by this Court in Justice K.S. Puttaswamy, the

Court will strike a balance, wherever a conflict between two

sets of fundamental rights is projected. Strictly speaking,

what is actually conceived by some and noted in several

decisions including Justice K.S. Puttaswamy, is not the

conflict of rights in abstractum, at a doctrinal level, but the

conflict in the notion/invocation/practice of rights;

(xviii) On the issue of statements made by Ministers and

collective responsibility, a reference has to be made to

Articles 75(3) and 164(2). Both these Articles speak of

collective responsibility of the Council of Ministers. Though

the language employed in these Articles indicate that such

a collective responsibility is to the House of the People/

Legislative Assembly, it is actually a responsibility to the

people at large. Since every utterance by a Minister will

have a direct bearing on the policy of the Government,

there is an imperative need for a voluntary code of

conduct. As pointed out by this Court in Common Cause

25

(supra), collective responsibility has two meanings, namely,

(i) that all members of the Council of Ministers are

unanimous in support of its policies and exhibit such

unanimity in public; and (ii) that they are personally and

morally responsible for its success and failure;

(xix) Individual aberrations on the part of Ministers are serious

threats to constitutional governance and as such the head

of the Council of Ministers has a duty to ensure that such

breaches do not happen;

(xx) A code of conduct to self-regulate the speeches and actions

of Ministers is constitutionally justifiable and this Court

can definitely examine its requirement. Ideally, a Minister

is not supposed to breach his collective responsibility

towards the Cabinet and the Legislature and hence, it is

advisable to have a cogent code of conduct as occurring in

advanced democracies;

(xxi) While it is not possible to impose additional restrictions on

the freedom of speech, it is certainly desirable to have a

code of conduct for public functionaries, as followed in

other jurisdictions. The Court may keep in mind the fact

that this Court in Sahara India Real Estate

Corporation Limited (supra) cautioned against framing

guidelines across the board to restrict the freedom of Press;

26

(xxii) Coming to hate speeches, there has been a steep increase

in the number of hate speeches since 2014. From May-

2014 to date, there have been 124 reported instances of

derogatory speeches by 45 politicians. Social media

platforms have connived the proliferation of targeted hate

speech. Such speeches provide fertile ground for

incitement to violence;

(xxiii) On the role of the Court in dealing with the question of

hate speech, the decisions in Pravasi Bhalai Sangathan

vs. Union of India

40

; Kodungallur Film Society vs.

Union of India

41

and Amish Devgan (supra) lay down

broad parameters;

(xxiv) At the international level, the definition of hate speech was

formulated in the UN Strategy and Plan of Action on Hate

Speech, to mean

“… any kind of communication in speech, writing or

behavior, that attacks or uses pejorative or

discriminatory language with reference to a person

or a group on the basis of who they are, in other

words, based on their religion, ethnicity,

nationality, race, colour, descent, gender or other

identity factor.”

The Role and Responsibilities of Political Leaders in

Combating Hate Speech and Intolerance (Provisional

version) dated 12 March 2019, was submitted by the

40 (2014) 11 SCC 477

41 (2018) 10 SCC 713

27

Committee on Equality and Non-Discrimination to the

Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe. The

Assembly passed the resolution adopting the text proposed

by rapporteur Ms. Elvira Kovacs, Serbia;

(xxv) Finally, the way forward is, (i) for the legislature to adopt a

voluntary model code of conduct for persons holding public

offices, which would reflect Constitutional morality and

values of good governance; and (ii) the creation of an

appropriate mechanism such as Ombudsman, in

accordance with the Venice principles and Paris principles.

Till such an Ombudsman is constituted, the National and

State Human Rights Commissions have to take pro-active

measures, in terms of the provisions of Protection of

Human Rights Act, 1993.

IV. Discussion and Analysis

Question No. 1

12. Question No.1 referred to us, is as to whether the grounds

specified in Article 19(2) in relation to which reasonable restrictions

on the right to free speech can be imposed by law are exhaustive, or

can restrictions on the right to free speech be imposed on grounds

not found in Article 19(2) by invoking other fundamental rights?

28

History of evolution of clause (2) of Article 19

13. For finding an answer to this question, it may be necessary

and even relevant to take a peep into history. Since Dr. B.R.

Ambedkar’s original draft in this regard followed Article 40(6) of the

Irish Constitution, the original draft of the Advisory Committee

included restrictions such as public order, morality, sedition,

obscenity, blasphemy and defamation. Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel

suggested the inclusion of libel also. These restrictions were sought

to be justified by citing the decision in Gitlow vs. New York

42

.

14. Since the country had witnessed large scale communal riots at

that time, Sir Alladi Krishnaswamy Iyer forcefully argued for the

inclusion of security and defence of the State or national security as

one of the restrictions. Discussion also took place about restricting

speech that is intended to spoil communal harmony and speech

which is seditious in nature. With suggestions, counter suggestions

and objections so articulated, the initial report of the Sub-

Committee on Fundamental Rights underwent a lot of changes. The

evolution of clauses (1) and (2) of Article 19 stage by stage, from the

42 286 US 652 (1925)

29

time when the draft report was submitted in April 1947, upto the

time when the Constitution was adopted, can be presented in a

tabular form

43

as follows:

Draft Provision

Draft Report of the

Subcommittee on

Fundamental Rights, April

1947 (BSR II, 139)

9. There shall be liberty for the exercise of

the following rights subject to public order

and morality:

(a) The right of every citizen to freedom of

speech and expression. The publication or

utterance of seditious, obscene, slanderous,

libellous or defamatory matter shall be

actionable or punishable in accordance with

law.

Final Report of the Sub-

Committee on Fundamental

Rights, April 1947 (BSR II,

172)

10. There shall be liberty for the exercise of

the following rights subject to public order

and morality or to the existence of grave

emergency declared to be such by the

Government of the Union or the unit

concerned whereby the security of the Union

or the unit, as the case may be.

Interim Report of the

Advisory Committee, April

30, 1947

There shall be liberty for the exercise of the

following rights subject to public order and

morality or to the existence of grave

emergency declared to be such by the

Government of the Union or the Unit

concerned whereby the security of the Union

or the Unit, as the case may be, is

threatened:

(a) The right of every citizen to freedom of

speech and expression:

Provision may be made by law to make the

publication or utterance of seditious,

obscene, blasphemous, slanderous, libellous

or defamatory matter actionable or

punishable.

Draft Constitution prepared 15. (1) There shall be liberty for the exercise

43 Sourced from the article “Arguments from Colonial Continuity- the Constitution (First

Amendment) Act, 1951” (2008) of Burra, Arudra, Assistant Professor, Department of

Humanities and Social Sciences , IIT (Delhi),

30

by B. N. Rau, October 1947

(BSR III, 8-9)

of the following rights subject to public order

and morality, namely:

(a) the right of every citizen to freedom of

speech and expression;

…

(2) Nothing in this section shall restrict the

power of the State to make any law or to take

any executive action which under this

Constitution it has power to make or to take,

during the period when a Proclamation of

Emergency issued under sub-section (I) of

section 182 is in force, or, in the case of a

unit during the period of any grave

emergency declared by the Government of

the unit whereby the security of the unit is

threatened.

Draft Constitution prepared

by the Drafting Committee

and submitted to the

President of the Constituent

Assembly, February 1948

(BSR III, 522)

13. (1) Subject to the other provisions of this

Article, all citizens shall have the right –

(a) to freedom of speech and expression;

…

(2) Nothing in sub-clause (a) of clause (1) of

this Article shall affect the operation of any

existing law, or prevent the State from

making any law, relating to libel, slander,

defamation, sedition or any other matter

which offends against decency or

morality or undermines the authority or

foundation of the State.

Proposal introduced in the

Constituent Assembly in

October 1948 (BSR IV, 39)

13. (1) Subject to the other provisions of this

Article, all citizens shall have the right –

(a) to freedom of speech and expression;

…

(2) Nothing in sub-clause (a) of clause (1) of

this article shall affect the operation of any

existing law, or prevent the State from

making any law, relating to libel, slander,

defamation, sedition or any other matter

which offends against decency or morality or

undermines the security of, or tends to

overthrow, the State.

31

Revised Draft Constitution,

introduced and adopted in

November 1949 (BSR IV,

755)

19. (1) All citizens shall have the right ---

(a) to freedom of speech and expression;

…

(2) Nothing in sub-clause (a) of clause (1)

shall affect the operation of any existing law

in so far as it relates to, or prevent the State

from making any law relating to, libel,

slander, defamation, contempt of Court or

any matter which offends against decency or

morality or which undermines the security

of, or tends to overthrow, the State.

15. Immediately after the adoption of the Constitution, this Court

had an occasion to deal with a challenge to an order passed by the

Government of Madras in exercise of the powers conferred by

Section 9(1-A) of the Madras Maintenance of Public Order Act,

1949

44

, banning the entry and circulation of a weekly journal called

‘Cross Roads’ printed and published in Bombay. The ban order was

challenged on the ground that it was violative of Article 19(1)(a).

The validity of the statutory provision under which the ban order

was issued, was also attacked on the basis of Article 13(1) of the

Constitution. A Seven Member Constitution Bench of this Court,

while upholding the challenge in Romesh Thappar vs. State of

Madras

45

held as follows: -

44 1949 Act

45 AIR 1950 SC 124

32

“[12] We are therefore of opinion that unless a law

restricting freedom of speech and expression is

directed solely against the undermining of the security

of the State or the overthrow of it, such law cannot fall

within the reservation under clause (2) of Art. 19,

although the restrictions which it seeks to impose may

have been conceived generally in the interests of public

order. …”

16. An argument was advanced in Romesh Thappar (supra) that

Section 9(1-A) of the 1949 Act could not be considered wholly void,

as the securing of public safety or maintenance of public order

would include the security of the State and that therefore the said

provision, as applied to the latter purpose was covered by Article

19(2). However, the said argument was rejected on the ground that

where a law purports to authorise the imposition of restrictions on

a fundamental right, in language wide enough to cover restrictions,

both within or without the limits of Constitutionally permissible

legislative action affecting such right, it is not possible to uphold it

even so far as it may be applied within the Constitutional limits, as

it is not severable.

17. On the same date on which the decision in Romesh Thappar

was delivered, the Constitution Bench of this Court also delivered

another judgment in Brij Bhushan vs. The State of Delhi

46

. It also

46 AIR 1950 SC 129

33

arose out of a writ petition under Article 32 challenging an order

passed by the Chief Commissioner of Delhi in exercise of the powers

conferred by Section 7(1)(c) of the East Punjab Public Safety Act,

1949, requiring the Printer and the Publisher as well as the Editor

of an English weekly by name ‘Organizer’, to submit for scrutiny,

before publication, all communal matters and news and views

about Pakistan including photographs and cartoons, other than

those derived from the official sources. Following the decision in

Romesh Thappar, the Constitution Bench held that the imposition

of pre-censorship on a journal is a restriction on the liberty of the

Press, which is an essential part of the right to freedom of speech

and expression. The Bench went on to hold that Section 7(1)(c) of

the East Punjab Public Safety Act, 1949 does not fall within the

reservation of clause (2) of Article 19.

18. After aforesaid two decisions, the Parliament sought to amend

the Constitution through the Constitution (First Amendment) Bill,

1951. In the Statement of Objects and Reasons to the First

Amendment, it was indicated that the citizen's right to freedom of

speech and expression guaranteed by Article 19(1)(a) has been held

34

by some Courts to be so comprehensive as not to render a person

culpable, even if he advocates murder and other crimes of violence.

Incidentally, the First Amendment also dealt with other issues,

about which we are not concerned in this discussion. Clause (2) of

Article 19 was substituted by a new clause under the Constitution

(First Amendment) Act, 1951. For easy appreciation of the

metamorphosis that clause (2) of Article 19 underwent after the first

amendment, we present in a tabular column, Article 19(2) pre-first

amendment and post-first amendment as under: -

Pre-First Amendment – Article

19(2)

Post-First Amendment – Article

19(2)

(2) Nothing in sub-clause (a) of clause

(1) shall affect the operation of any

existing law in so far as it relates to,

or prevents the State from making

any law relating to, libel, slander,

defamation, contempt of court or any

matter which offends against decency

or morality or which undermines the

security of, or tends to overthrow, the

State.

(2) Nothing in sub-clause (a) of

clause (1) shall affect the operation

of any existing law, or prevent the

State from making any law, in so far

as such law imposes reasonable

restrictions on the exercise of the

right conferred by the said sub-

clause in the interests of the

security of the State, friendly

relations with foreign States, public

order, decency or morality, or in

relation to contempt of court,

defamation or incitement to an

offence.

19. It is significant to note that Section 3(1)(a) of the Constitution

(First Amendment) Act, 1951, declared that the newly substituted

35

clause (2) of Article 19 shall be deemed always to have been

enacted in the amended form, meaning thereby that the

amended clause (2) was given retrospective effect.

20. Another important feature to be noted in the amended clause

(2) of Article 19 is the inclusion of the words ‘reasonable

restrictions’. Thus, the test of reasonableness was introduced by the

first amendment and the same fell for jural exploration within no

time, in State of Madras vs. V.G. Row

47

. The said case arose out

of a judgment of the Madras High Court quashing a Government

Order declaring a society known as ‘People’s Education Society’ as

an unlawful association and also declaring as unconstitutional,

Section 15(2)(b) of the Indian Criminal Law Amendment Act, 1908,

as amended by the Indian Criminal Law Amendment (Madras) Act,

1950. While upholding the judgment of the Madras High Court, this

Court indicated as to how the test of reasonableness has to be

expounded. The relevant portion of the judgment reads as follows: -

“23. It is important in this context to bear in mind that

the test of reasonableness, wherever prescribed,

should be applied to each individual statute impugned,

and no abstract standard, or general pattern of

47(1952) 1 SCC 410

36

reasonableness can be laid down as applicable to all

cases. The nature of the right alleged to have been

infringed, the underlying purpose of the

restrictions imposed, the extent and urgency of the

evil sought to be remedied thereby, the

disproportion of the imposition, the prevailing

conditions at the time, should all enter into the

judicial verdict. In evaluating such elusive factors

and forming their own conception of what is

reasonable, in all the circumstances of a given

case, it is inevitable that the social philosophy and

the scale of values of the Judges participating in

the decision should play an important part, and the

limit to their interference with legislative

judgment in such cases can only be dictated by

their sense of responsibility and self-restraint and

the sobering reflection that the Constitution is

meant not only for people of their way of thinking

but for all, and that the majority of the elected

representatives of the people have, in authorizing

the imposition of the restrictions, considered them

to be reasonable.”

21. After the First Amendment to the Constitution, the country

witnessed cries for secession, with parochial tendencies showing

their ugly head, especially from a southern State. Therefore, a

National Integration Conference was convened in September-

October, 1961 to find ways and means to combat the evils of

communalism, casteism, regionalism, linguism and narrow

mindedness. This Conference decided to set up the National

Integration Council. Accordingly, it was constituted in 1962. The

constitution of the Council assumed significance in the wake of the

37

Sino-India war in 1962. This National Integration Council had a

Committee on national integration and regionalism. This Committee

recommended two amendments to the Constitution, namely, (i) the

amendment of clause (2) of Article 19 so as to include the words

“the sovereignty and integrity of India” as one of the restrictions; and

(ii) the amendment of 8 Forms of oath or affirmation contained in

the Third Schedule. Until 1963, no one taking a constitutional oath

was required to swear that they would “uphold the sovereignty and

integrity of India”. But, the Constitution (Sixteenth Amendment) Act,

1963 expanded the forms of oath to ensure that “every candidate

for the membership of a State Legislature or Parliament, and every

aspirant to, and incumbent of, public office” – to quote its Statement

of Objects and Reasons – “pledges himself . . . to preserve the

integrity and sovereignty of the Union of India.” Thus, by the

Constitution (Sixteenth Amendment) Act, 1963, “the sovereignty

and integrity of India”, was included as an additional ground of

restriction on the right guaranteed under Article 19(1)(a).

22. Having seen the history of evolution of clause (2) of Article 19,

let us now turn to the first question.

38

Two parts of Question No.1

23. Question No.1 is actually in two parts. The first part raises a

poser as to whether reasonable restrictions on the right to free

speech enumerated in Article 19(2) could be said to be exhaustive.

The second part of the Question raises a debate as to whether

additional restrictions on the right to free speech can be imposed on

grounds not found in Article 19(2), by invoking other fundamental

rights.

First part of Question No.1

24. The judicial history of the evolution of clause (2) of Article 19

which we have captured above shows that lot of deliberations went

into the articulation of the restrictions now enumerated. The draft

Report of the Sub-Committee on Fundamental Rights itself

underwent several changes until the Constitution was adopted in

November, 1949. In the form in which the Constitution was adopted

in 1949, the restrictions related to (i) libel; (ii) slander; (iii)

defamation; (iv) contempt of court; (v) any matter which offends

39

against decency or morality; and (vi) any matter which undermines

the security of the State or tends to overthrow the State.

25. After the 1

st

and 16

th

Amendments, the emphasis is on

reasonable restrictions relating to, (i) interests of sovereignty and

integrity of India; (ii) the security of the State; (iii) friendly relations

with foreign states; (iv) public order; (v) decency or morality; (vi)

contempt of court; (vii) defamation; and (viii) incitement to an

offence.

26. A careful look at these eight heads of restrictions would

show that they save the existing laws and enable the State to

make laws, restricting free speech with a view to afford

protection to (i) individuals (ii) groups of persons (iii) sections

of society (iv) classes of citizens (v) the Court (vi) the State and

(vii) the country. This can be demonstrated by providing in a table,

the provisions of the Indian Penal Code that make some speech or

expression a punishable offence, thereby impeding the right to free

speech, the heads of restriction under which they fall and the

40

category/class of person/persons sought to be protected by the

restriction:

Table of Provisions under IPC restricting freedom of speech and expression

Laws restricting free

speech

Heads of Restriction

traceable to Article 19(2)

Person/Class of Person

sought to be protected

and the nature of

protection.

Section 117 of the IPC

-Abetting commission of

offence by the public or by

more than ten persons.

There is an illustration

under the section which

forms part of the statute.

This illustration seeks to

restrict freedom of

expression

Illustration:

A affixes in a public place a

placard instigating a sect

consisting of more than ten

members to meet at a

certain time and place, for

the purpose of attacking the

members of an adverse sect,

while engaged in a

procession. A has committed

the offence defined in this

section.

1. Public Order

2. Incitement to an Offence

Individual Persons -

Protection from

incitement to commit

offence.

Section 124A of the IPC -

Sedition

48

1. Public Order

2. Decency and Morality

State – Protection against

disaffection

Section 153A(1)(a) of the

IPC - Promoting enmity

between different groups on

ground of religion, race,

place of birth, residence,

language, etc., and doing

acts prejudicial to

maintenance of harmony

1.Public Order

2. Decency and Morality

Groups of Persons -

Protection from

disrupting harmony

among different sections

of society.

48 Subject matter of challenge pending before this Court.

41

Section 153B of the IPC -

Imputations, assertions

prejudicial to the national-

integration

1. Sovereignty and

Integrity of the State

2. Public Order

3. Decency and Morality

1. Nation

2. Group of persons

belonging to different

religions, races,

languages, etc,.

Section 171C of the IPC

-Undue Influence at

Elections

1. Public Order Candidates contesting

the Election and Voters –

To ensure free and fair

election and to keep the

purity of the democratic

process

Section 228 of the IPC -

Intentional insult or

interruption to public

servant sitting in judicial

proceedings

Contempt of Court Court –To prevent people

from undermining the

authority of the court.

Section 228A of the IPC-

Disclosure of identity of the

victim of certain offences

etc.

1. Public Order

2. Decency and Morality

Individual persons

(Victims of offences u/s

376)- Protection of

identity of women and

minors.

Section 295A of the IPC -

Deliberate and malicious

acts, intended to outrage

religious feelings of any

class by insulting its

religion or religious beliefs.

1. Public order,

2. Decency and morality

Sections of society

professing and practicing

different religious

beliefs/sentiments.

Section 298 of the IPC-

Uttering words, etc., with

deliberate intent to wound

religious feelings.

1. Public order,

2. Decency and morality

Sections of society

professing and practicing

different religious

beliefs/sentiments.

Section 351 of the IPC –

Assault. The definition of

assault includes some

utterances, as seen from

the Explanation under the

Section.

Explanation:

Mere words do not amount

to an assault. But the words

which a person uses may

give to his gestures or

preparation such a meaning

1. Public Order

2. Decency and morality

Individual Persons –

Protection from Criminal

Force.

42

as may make those gestures

or preparations amount to

an assault.

Section 354 of the IPC-

Assault to woman with

intent to outrage her

modesty

Note:

The Definition of Assault

includes the use of words.

1. Public Order

2. Decency and morality

3. Defamation

Individual Persons –

Protection of Modesty of

a Woman.

Section 354A of the IPC –

Sexual Harassment (It

includes sexually colored

remarks).

1. Public Order

2. Decency and morality

3. Defamation

Individuals – Protection

of Modesty of a Woman.

Section 354C of the IPC –

Voyeurism

1. Public Order

2. Decency and morality

3. Defamation

Individuals – Protection

of Modesty of a Woman.

Section 354D of the IPC –

Stalking

1. Decency and Morality

2. Defamation

Individuals – Protection

of Modesty of a Woman.

Section 354E of the IPC –

Sextortion

1. Public Order

2. Decency and morality

3. Defamation

Individual Persons –

Protection of Modesty of

a Woman.

Section 355 of the IPC -

Assault or criminal force

with intent to dishonour

person, otherwise than on

grave provocation.

Note:

The Definition of Assault

includes use of words.

1. Public Order

2. Decency and morality

3. Defamation

Individual Persons –

Protection of reputation.

Section 383 of the IPC –

Extortion (The illustration

under the Section includes

threat to publish

defamatory libel).

Illustration:

A threatens to publish a

defamatory libel concerning

Z unless Z gives him money.

He thus induces Z to give

1. Public Order

2. Decency and Morality

Individuals – Protection

from fear of injury/

Protection of Property.

43

him money. A has

committed extortion.

Section 390 of the IPC –

Robbery

Note:

In all robbery there is either

theft or extortion.

1. Public Order

2. Decency and Morality

Individuals – Protection

from fear of injury/

Protection of Property.

Section 499 of the IPC –

Defamation

Defamation Individual Persons and

Group of People –

Reputation sought to be

protected.

Section 504 of the IPC –

Intentional insult with

intent to provoke breach of

peace.

1. Incitement to an offense

2. Public Order

3. Decency and morality

The public – Protection of

Peace.

Section 505(1)(b) of the IPC

– Statement likely to cause

fear or alarm to the public

whereby any person may be

induced to commit an

offence against the State or

against the public

tranquility.

1. Sovereignty and Integrity

of the State

2. Incitement to an offense

3. Public Order

State – Protection from

the commission of

offences against the State

and protection of public

tranquility.

Section 505(1)(c) of the IPC-

Statement intended to incite

any class or community of

persons to commit any

offence against any other

class or community.

Public Order Class/community of

people.

Protection from

incitement to commit

violence against class or

community.

Section 509 of the IPC –

Word, Gesture or Act

intended to insult the

modesty of a woman.

1. Defamation

2. Decency or Morality

Individual persons –

Protection of Modesty of

a Woman.

27. We have taken note of, in the above Table, only the provisions

of the Indian Penal Code that curtail free speech. There are also

other special enactments such as The Scheduled Castes and The

44

Scheduled Tribes (Prevention of Atrocities) Act, 1989, The

Prevention of Insults to National Honour Act, 1971 etc., which also

impose certain restrictions on free speech. From these it will be

clear that the eight heads of restrictions contained in clause (2) of

Article 19 are so exhaustive that the laws made for the purpose of

protection of the individual, sections of society, classes of citizens,

court, the country and the State have been saved.

28. The restrictions under clause (2) of Article 19 are

comprehensive enough to cover all possible attacks on the

individual, groups/classes of people, the society, the court, the

country and the State. This is why this Court repeatedly held that

any restriction which does not fall within the four corners of Article

19(2) will be unconstitutional. For instance, it was held by the

Constitution Bench in Express Newspapers (Private) Ltd. vs. The

Union of India

49

, that a law enacted by the legislature, which does

not come squarely within Article 19(2) would be struck down as

unconstitutional. Again, in Sakal Papers (supra), this Court held

that the State cannot make a law which directly restricts one

freedom even for securing the better enjoyment of another freedom.

491959 SCR 12

45

29. That the Executive cannot transgress its limits by imposing an

additional restriction in the form of Executive or Departmental

instruction was emphasised by this Court in Bijoe Emmanuel vs.

State of Kerala

50

. The Court made it clear that the reasonable

restrictions sought to be imposed must be through “a law” having

statutory force and not a mere Executive or Departmental

instruction. The restraint upon the Executive not to have a

back-door intrusion applies equally to Courts. While Courts

may be entitled to interpret the law in such a manner that the

rights existing in blue print have expansive connotations, the Court

cannot impose additional restrictions by using tools of

interpretation. What this Court can do and how far it can afford to

go, was articulated by B. Sudharshan Reddy, J., in Ram

Jethmalani (supra) as follows:

“85. An argument can be made that this Court can

make exceptions under the peculiar circumstances of

this case, wherein the State has acknowledged that it

has not acted with the requisite speed and vigour in the

case of large volumes of suspected unaccounted for

monies of certain individuals. There is an inherent

danger in making exceptions to fundamental principles

and rights on the fly. Those exceptions, bit by bit, would

then eviscerate the content of the main right itself.

50(1986) 3 SCC 615

46

Undesirable lapses in upholding of fundamental rights

by the legislature, or the executive, can be rectified by

assertion of constitutional principles by this Court.

However, a decision by this Court that an exception

could be carved out remains permanently as a part of

judicial canon, and becomes a part of the constitutional

interpretation itself. It can be used in the future in a

manner and form that may far exceed what this Court

intended or what the constitutional text and values can

bear. We are not proposing that Constitutions cannot be

interpreted in a manner that allows the nation-State to

tackle the problems it faces. The principle is that

exceptions cannot be carved out willy-nilly, and without

forethought as to the damage they may cause.

86.One of the chief dangers of making exceptions to

principles that have become a part of constitutional law,

through aeons of human experience, is that the logic,

and ease of seeing exceptions, would become

entrenched as a part of the constitutional order. Such

logic would then lead to seeking exceptions, from

protective walls of all fundamental rights, on grounds of

expediency and claims that there are no solutions to

problems that the society is confronting without the

evisceration of fundamental rights. That same logic

could then be used by the State in demanding

exceptions to a slew of other fundamental rights,

leading to violation of human rights of citizens on a

massive scale.”

30. Again, in Secretary, Ministry of Information &

Broadcasting, Govt. of India vs. Cricket Association of

Bengal

51

, this Court cautioned that the restrictions on free speech

can be imposed only on the basis of Article 19(2). In Ramlila

Maidan Incident, in re.

52

, this Court developed a three-pronged

51(1995) 2 SCC 161

52 (2012) 5 SCC 1

47

test namely, (i) that the restriction can be imposed only by or under

the authority of law and not by exercise of the executive power; (ii)

that such restriction must be reasonable; and (iii) that the

restriction must be related to the purposes mentioned in clause (2)

of Article 19.

31. That the eight heads of restrictions contained in clause (2) of

Article 19 are exhaustive can be established from another

perspective also. The nature of the restrictions on free speech

imposed by law/judicial pronouncements even in countries where a

higher threshold is maintained, are almost similar. To drive home

this point, we are presenting in the following table, a comparative

note relating to different jurisdictions:

Jurisdiction The Document

from which the

Right to Freedom

of Speech and

Expression flows

The Document

from which the

restrictions on

the right to

freedom of

Speech and

Expression flow

Nature of

Restrictions

India Article 19(1)(a) -

Constitution of

India

Article 19(2) -

Constitution of

India

1. Sovereignty and

integrity of the

State,

2. Security of the

State,

3. Friendly relations

48

with foreign

countries,

4. Public order,

5. Decency and

morality,

6. Contempt of court,

7. Defamation,

8. Incitement to an

offense.

UK Article 10(1) of the

Human Rights Act,

1998

Article 10(2) of the

Human Rights Act,

1998

1. National security,

2. Territorial integrity

or public safety,

3. For the prevention

of disorder or

crime, for the

protection of

health or morals,

4. For the protection

of the reputation

or rights of others,

5. For preventing the

disclosure of

information

received in

confidence, or

6. For maintaining

the authority and

impartiality of the

judiciary.

USA First Amendment

to the US

Constitution

No restriction is

specifically

provided in the

Constitution. But

Judicial Review by

the Supreme Court

has admitted

certain restrictions

Recognised forms of

Unprotected Speech:

1. Obscenity as held

in Roth v. United

States, 354 U.S. 476,

483 (1957).

2.Child Pornography

as held in Ashcroft v.

Free Speech Coalition,

435 U.S. 234 (2002).

3. Fighting Words

49

and True Threat as

held in Chaplinsky v.

New Hampshire, 315

U.S. 568 (1942) and

Virginia v. Black, 538

U.S. 343, 363 (2003),

respectively.

Australia Australian

Constitution does

not expressly

speak about

freedom of

expression.

However, the High

Court has held

that an implied

freedom of political

communication

exists as an

indispensible part

of the system of

representative and

responsible

government

created by the

Constitution. It

operates as a

freedom from

government

restraint, rather

than a right

conferred directly

on individuals.

Australia is a party

to seven core

international

human rights

treaties. The right

to freedom of

opinion and

expression is

contained in

Articles 19 and 20

of the International

Covenant on Civil

and Political

Rights (ICCPR)and

Articles 4 and 5 of

1. Article 19(3), 20

of the ICCPR

contains

mandatory

limitations on

freedom of

expression, and

requires countries,

subject to

reservation/declar

ation, to outlaw

vilification of

persons on

national, racial or

religious grounds.

Australia has

made a declaration

in relation to

Article 20 to the

effect that existing

Commonwealth

and state

legislation is

regarded as

adequate, and that

the right is

reserved not to

introduce any

further legislation

imposing further

restrictions on

these matters.

2. Criminal Code

Act 1995

3. Racial

Discrimination

Act 1975

Under International

Treaties:

1. Rights of

Reputation of

Others,

2. National Security,

3. Public Order,

4. Public Health, or

5. Public Morality

Under the Criminal

Code Act, 1995

1.Offences relating to

urging by force or

violence the overthrow

of the Constitution or

the lawful authority of

the Government; and

2. Offences relating to

the use of a

telecommunications

carriage service in a

way which is

intentionally

menacing, harassing

or offensive, and

using a carriage

service to

communicate content

which is menacing,

harassing or

offensive.

Speech or

Expression

amounting to Racial

50

the Convention on

the Elimination of

All Forms of Racial

Discrimination

(CERD) , Articles

12 and 13 of the

Convention on the

Rights of the Child

(CRC) and Article

21 of the

Convention on the

Rights of Persons

with Disabilities

(CRPD).

Discrimination

under the Racial

Discrimination Act,

1975

European

Union

Article 10(1),

European

Convention on

Human Rights,

1950

Article 10(2),

European

Convention on

Human Rights,

1950

1. In the interests of

national security,

territorial integrity

or public safety,

2. For the prevention

of disorder or

crime,

3. For the protection

of health or

morals,

4. For the protection

of the reputation

or rights of others,

5. For preventing the

disclosure of

information

received in

confidence, or

6. For maintaining

the authority and

impartiality of the

judiciary.

Republic of

South Africa

Bill of Rights,

Article 16(1) of the

Constitution of the

Republic of South

Africa, 1996

Bill of Rights,

Article 16(2) of the

Constitution of the

Republic of South

Africa, 1996

1. Propaganda for

war,

2. Incitement of

imminent violence,

3. Advocacy of hatred

that is based on

race, ethnicity,

gender, religion,

and that

51

constitutes

incitement to

cause harm.

32. Since the eight heads of restrictions contained in clause (2) of

Article 19 seek to protect:

(i) the individual – against the infringement of his dignity,

reputation, bodily autonomy and property;

(ii) different sections of society professing and practicing, different

religious beliefs/sentiments - against offending their beliefs and

sentiments;

(iii) classes/groups of citizens belonging to different races, linguistic