2023 AAHA Management of Allergic Skin Diseases

in Dogs an d Ca ts Guidelines

Julia Miller, DVM, DACVD,

†

Andrew Simpson, DVM, MS, DACVD,

†

Paul Bloom, DVM, DACVD, DABVP (Canine and Feline), Alison Diesel, DVM, DACVD,

Amanda Friedeck, BS, LVT, VTS (Dermatology), Tara Paterson, DVM, MS, Michelle Wisecup, DVM,

Chih-Ming Yu, DVM, MPH, ECFVG

ABSTRACT

These guidelines present a systematic approach to diagnosis, treatment, and management of allergic skin diseases in

dogs and cats. The guidelines describe detailed diagnosis and treatment plans for flea allergy, food allergy, and atopy in

dogs and for flea allergy, food allergy, and feline atopic skin syndrome in cats. Management of the allergic patient entails

a multimodal approach with frequent and ongoing communication with the client. Obtaining a comprehensive history is

crucial for diagnosis and treatment of allergic skin diseases, and the guidelines describe key questions to ask when presented

with allergic canine and feline patients. Once a detailed history is obtained, a physical examination should be performed, a

minimum dermatologic database collected, and treatment for secondary infection, ectoparasites, and pruritus (where indi-

cated) initiated. The process of diagnosing and managing allergic skin disease can be prolonged and frustrating for clients.

The guidelines offer recommendations and tips for client communication and when referral to a dermatologist should be

considered, to improve client satisfaction and optimize patient outcomes. (JAmAnimHospAssoc2023; 59:

䊏䊏䊏

–

䊏䊏䊏

.

DOI 10.5326/JAAHA-MS-7396)

AFFILIATIONS

Animal Dermatology Clinic, Louisville, Kentucky (J.M.); VCA Aurora

Animal Hospital, Aurora, Illinois (A.S.); Allergy, Skin and Ear Clinic for Pets,

Livonia, Michigan (P.B.); Animal Dermatology Clinic-Austin, Austin, Texas

(A.D.); Texas A&M University, College Station, Texas (A.F.); St. George’s

University, St. George’s, Grenada (T.P.); The Ohio State University,

Columbus, Ohio (M.W.); U-Vet Animal Clinic, Newburgh, Indiana (C-M.Y.)

CONTRIBUTING REVIEWERS

Lindsay McKay, DVM, DACVD, VCA Arboretum View Animal Hospital

Karen Trainor, DVM, MS, DACVP, Innovative Vet Path

Amelia White, DVM, MS, DACVD, Auburn University

Correspondence: [email protected]

†

J. Miller and A. Simpson are the cochairs of the AAHA Management

of Allergic Skin Diseases in Dogs and Cats Guidelines Task Force.

AAHA gratefully acknowledges the contribution of our task force

facilitator and writer, J.P. O’Connor, FASAE, in the preparation of this

manuscript.

These guidelines were prepared by a task force of experts convened by

the American Animal Hospital Association. This document is intended as

a guideline only, not an AAHA standard of care. These guidelines and

recommendations should not be construed as dictating an exclusive

protocol, course of treatment, or procedure. Variations in practice may

be warranted based on the needs of the individual patient, resources,

and limitations unique to each individual practice setting. Evidence-

guided support for specific recommendations has been cited whenever

possible and appropriate. Other recommendations are based on

practical clinical experience and a consensus of expert opinion. Further

research is needed to document some of these recommendations. Drug

approvals and labeling are current at the time of writing but may change

over time. Because each case is different, veterinarians must base their

decisions on the best available scientific evidence in conjunction with

their own knowledge and experience.

The 2023 AAHA Management of Allergic Skin Diseases in Dogs and

Cats Guidelines are generously supported by Hill’s Pet Nutrition Inc.,

Merck, and Zoetis.

AOE (allergic otitis externa); ASIT (allergen-specific immunotherapy);

DTM (dermatophyte test medium); FASS (feline atopic skin syndrome);

OTC (over the counter); PO (per os); SBF (superficial bacterial folliculitis);

SOC (spectrum of care)

Technician utilization

recommendation

Spectrum of care

recommendation

Referral

recommendation

© 2023 by American Animal Hospital Association JAAHA.ORG 1

VETERINARY PRACTICE GUIDELINES

Introduction

An itchy pet is one of the most common reasons a client seeks veter-

inary care. Allergic skin diseases can cause not only significant

discomfort and distress to the individual animal but also stress and

disruption to the pet’s family members. Because of the complex

nature of allergic skin disease, diagnosis can be time-consuming and

may require multiple follow-up visits before a final diagnosis is

achieved. Patients with allergic skin disease often require lifelong

management to optimize their quality of life. These guidelines offer a

step-by-step approach to diagnose and manage flea allergy, food

allergy, and atopy in the dog and cat.

Section 1 describes the steps in diagnosing the canine patient with

allergic skin disease.

Section 2 describes initial and long-term management of canine

allergic skin diseases and acute flares.

Section 3 addresses diagnosing allergy in the feline patient, including

clinical presentations of dermatitis in cats and key differences

between cats and dogs.

Section 4 describes initial and long-term management of feline aller-

gic skin diseases and acute flares.

Section 5 provides an overview of diagnosis and treatment of allergic

otitis externa.

Section 6 presents spectrum of care considerations for managing

allergic skin diseases, including referral recommendations, tele-

health, and communication tips.

Section 7 discusses the vital role of veterinary technicians in the

management of allergic patients and how to optimize their involve-

ment in these cases.

Section 8 offers key messaging points for client communication.

These guidelines are designed to simplify the path to diagnosis

and management of canine and feline allergic skin diseases, while

emphasizing a multimodal approach for the patient and effective cli-

ent communication to ensure the best possible outcome.

Section 1: Diagnosing the Allergic Canine

Patient

Top 3 Takeaways:

1. A detailed history, including a review of previous medical records,

should be obtained. Information regarding seasonality, pruritus

level, ectoparasite prevention, and response to previous therapies

are all paramount in the workup of the pruritic dog.

2. A minimum dermatologic database should be performed including

skin cytology, flea combing, skin scrapings, and ear cytology (if ear

disease is present).

3. Atopy is a diagnosis of exclusion. Allergy testing (intradermal or

serum) to identify allergens should only be performed if immuno-

therapy is planned.

Overview

Diagnosing allergic skin disease in the canine patient requires the

veterinary team to be well versed in obtaining accurate clinical histo-

ries that include key questions about the dog’s level of pruritus, the

environment, and any other medical conditions present. A minimum

dermatologic database should also be performed on pruritic patients

to assess for the presence of ectoparasites and skin infections.

Because atopy is a diagnosis of exclusion, the process may be time-

consuming and frustrating for clients. Clear communication regard-

ing timelines and expectations is crucial for successful results.

Step One: Clinical History and Dermatologic Physical

Examination

Clinical History

A detailed history should provide essential information about the

dog’s clinical signs, patterns of pruritus, and environment, which will

assist the practitioner in diagnosing the specific allergic disease.

When asking a client about the presence and intensity of pruritus, it

is important to clearly explain the signs of pruritus to owners who

may not readily recognize them. Clients may not understand that

scratching, biting, chewing, licking, gnawing, rubbing, or rolling can

all be evidence of an itchy dog. Pruritus scales (usually ranging from

1to10with10representingconstantitching)canbeahelpfultool

to use with clients. The validated canine Pruritus Visual Analog Scale

can be found at https://www.vetdermclinic.com/pruritus-visual-analog-

scale-canine/.

Educating clients and helping them to understand that each

question in the client history provides significant diagnostic clues

can make the process seem less of a formality and more like progress

toward the mutual goal of a more comfortable and happier dog.

Engaging clients in this way can create the sense that everyone is on

the same team, for what may be a long road ahead.

Veterinary technicians are an invaluable asset in

dermatologic appointments. From taking compre-

hensive clinical histories to educating clients, tech-

nicians serve a vital role in the workup and suc-

cessful management of pruritic patients.

Key Questions for Clinical History

1. What was the distribution of the pruritus initially? What is it now?

Have there been changes?

Note that only ectoparasites have a predictable distribution. The dis-

tribution of pruritus for atopy or food allergy is identical.

1

2. Is the pruritus seasonal, year-round, or year-round with a seasonal

flare?

Seasonal pruritus is most consistent with atopy. Year-round pruri-

tus may be associated with food allergy, atopy due to indoor aller-

gens, and atopy in certain geographical locations where outdoor

allergens lack seasonality.

3. What was the age of onset?

Food allergies may start at any age, but because atopy has a more

defined age of onset (i.e., clinical signs starting between 6 mo and

4yrofage),foodallergymaybeprioritizedintheveryyoungand

older patients.

2

Pruritus due to ectoparasites may present at any age.

2 JAAHA | 59:6 Nov/Dec 2023

4. What previous treatments were prescribed and how effective were they?

Response to treatments such as oclacitinib or lokivetmab will vary

among allergic patients. Response to glucocorticoids does not help

narrow the cause of pruritus as any pruritic disease may respond

to antipruritic doses of glucocorticoids. Failure to respond to gluco-

corticoids, however, may suggest the presence of secondary infections

(bacterial or Malassezia), ectoparasites, and/or food allergy. In addi-

tion, an incomplete response to antibiotic therapy may indicate the

presence of antimicrobial resistance. Commonly, antimicrobials and

antipruritic therapies are prescribed and discontinued at the same

time. To truly assess response to these therapies, it is helpful to avoid

discontinuat ion of these medications at the same time.

Complete response Partial response No response

Consider food

allergy concurrent

with atopy. Continue

diet trial while

treating for atopy.

Pruritus when diet

is challenged

Treat for atopy,

recheck MDB.

Ectoparasites were cleared vs seasonal atopy vs resolution

of secondary skin infections due to primary endocrinopathy

Nonseasonal Seasonal

Complete response AND

no return of pruritus after

medications stopped

Food allergy

Continue

hypoallergenic diet

Treat for atopy

Partial or no response OR return of pruritus after medications stopped

Presentation of dog:

Skin lesions +/- pruritus

STEP 1: Clinical History and Dermatologic

Physical Examination (skin AND ears)

STEP 3: Treat Pruritus (+/- oral glucocorticoid, oclacitinib, or lokivetmab, depending on severity)

STEP 4: Treat Secondary Infections, Ectoparasites, and OE

STEP 5: Recheck

STEP 6: Diet Trial

STEP 2: MDB (skin scraping,

skin cytology, +/- ear cytology)

MDB, minimum dermatologic database; OE, otitis externa

FIGURE 1

Diagnosing Allergic Skin Disease in the Canine Patient.

JAAHA.ORG 3

5. Are other pets or humans affected?

Pruritus affecting other pets or humans strongly suggests the pres-

ence of ectoparasites such as fleas, scabies, or Cheyletiella.

6. Is there any vomiting, soft stool, or increased flatulence that may sug-

gest a food allergy?

In addition to cutaneous signs, 19–27% of food-allergic dogs will

also exhibit vomiting, soft stool, and/or diarrhea.

3

Using a fecal score

chart can be beneficial (see https://www.proplanveterinarydiets.ca/

sites/g/files/2021-02/180107_PPPVD-Fecal-Scoring-Chart-UPDATE-

EN-FINAL.pdf).

Dermatologic Physical Examination

Perform a complete physical examination, including flea combing and

an otoscopic examination. An otoscopic examination should be per-

formed even if the owner does not report otic pruritus because it is

common for dogs to not show overt clinical signs of ear disease until

it is moderately severe. Note that up to 50% of allergic dogs may have

otitis externa

1

and this may be the first and only clinical signs of aller-

gicdisease.Besuretoassesstheskininareaswhereinflammatio n

may be less obvious, including the paws, claws, perianal skin, and

intertrigi nous areas such as the axillary and inguinal regions and skin

folds (see Figure 2). A complete nose-to-tail examination is essential

and may require sedation if an animal is very uncomfortabl e or resis-

tant to handling.

Flea combing should always be performed as part of

the initial physical examination.

Step Two: Minimum Dermatologic Database

A minimum dermatologic database should be collected as the next

step and consists of the following:

Cytology of skin and ears (where evidence of ear disease is present)

Skin scrapings (deep/superficial to assess for both Demodex and Sar-

coptes mites)

If there are financial constraints, consider a thera-

peutic trial with an isoxazoline, rather than per-

forming skin scrapings. However, be aware that

although uncommon, failures in the treatment of

mites using isoxazolines have been anecdotally

reported. A s alternatives to traditional deep skin

scrapings, plucking hairs (trichogram) or acetate

tape samples on pinched skin may be able to detect

Demodex mites in areas that are too sensitive for a

deep skin scrape.

6 Dermatophyte test medium (DTM) culture (depending on regional

prevalence, history, and index of suspicion)

Depending on state regulations, collecting samples

for a minimum dermatologic database may be

assigned to a veterinary technician.

Step Three: Treat Pruritus

A critical aspect in managing both the patient and the owner’squal-

ity of life is reducing pruritus. Consider the use of an antipruritic

agent (glucocorticoids, oclacitinib, or lokivetmab) and/or topical

therapy (see Table 1 and Section 2 for more information). These

therapies may be less effective in the face of active infection; there-

fore, appropriate diagnosis and treatment of secondary infections is

critical before assessing response to antipruritic therapy.

Step Four: Treat Secondary Infections and

Ectoparasites

Secondary bacterial and Malassezia infections must be treated con-

currently with controlling pruritus and diagnosing the underlying

allergic disease (see Tables 4 and 5). Otitis externa, if present, should

also be treated (see Section 5). Prescribe a flea and tick preventive if

the dog is not currently receiving one and discuss compliance with

the client. The guidelines task force prefers an oral isoxazoline as

this drug class offers flea, tick, and mite prevention and allows for

routine bathing. All parasiticides may lower seizure threshold, and

consultation with a neurologist is recommended in severely epileptic

patients.

Step Five: Recheck, Verify Medication, and Assess

Response to Treatment

Assessing the response to medications such as flea preventives and

antipruritic drugs is a key step in the diagnostic process. It is impor-

tant to ensure that the veterinary team and the client are all on the

same page about medication administration, duration of therapy,

and follow-up examinations. Response to therapy should be assessed

14 days after initiating therapy, and this is ideally done with an

in-person recheck examination. However, if a physical examination

is not feasible for the client, this would be a reasonable application

for a telehealth appointment. If multiple medications were pre-

scribed, it is recommended to discontinue these one at a time to help

determinewhich,ifany,wereresponsiblefortheresponse.Itisnot

ideal to stop antipruritic and antimicrobial therapies at the same

time as this muddies the water and does not allow you to inter-

pret what was causing the patient’sitch—the infection or the

allergic inflammation.

If the dog shows a full response to treatment (i.e., resolution of

pruritus, resolution of infection, skin lesions, etc.) after being weaned

off antipruritic therapy at the time of reassessment:

1. The diagnosis may be one of three things: ectoparasitism that has

now resolved, secondary infections that have now resolved, and/or

seasonal atopy.

4 JAAHA | 59:6 Nov/Dec 2023

FIGURE 2

Clinical Presentation of the Pruritic Canine Patient.

JAAHA.ORG 5

2. If a secondary infection was present, it may have been the

primary cause of the pruritus. Primary diagnoses to consider then

include:

a. Ectoparasites

b. Seasonal atopy

c. Endocrinopathy

i. If other clinical signs are present

ii. Note that these conditions are not pruritic unless secondary

infection is present

Next Steps

1. Continue routine use of flea/tick preventives.

2. If receiving antimicrobial therapy and the infection has resolved,

continue antimicrobial therapy for 7 days beyond clinical and cyto-

logical resolution (see Section 2 for more information).

3. If the history supports seasonal atopy, discuss management options

(see Section 2).

4. If the history supports an endocrinopathy, recommend additional

diagnostics.

TABLE 1

Antipruritic and Anti-inflammatory Medications for Dogs

Drug Name Oclacitinib

1

Lokivetmab

2

Cyclosporine

3

Glucocorticoids

4

Mode of action JAK-STAT inhibitor that

blocks signaling from

proinflammatory and

pruritogenic cytokines

Caninized monoclonal

antibody that

neutralizes the

pruritogenic cytokine

IL-31

Calcinurin inhibitor

that modulates T-cell

function

Influences gene

expression of

proinflammatory

cytokines

Administration PO

q 12 hr up to 14 days,

then reduce to q 24 hr

SC injection at

veterinary oce

q 4-8 wk

PO

q 24 hr

PO

q 12-24 hr with taper

Injectable not

recommended

Time to onset Hours Hours to 3 days 4-6 wk Hours

Age >1 yr Any >6 mo Any

Weight >3 kg Any >1.8 kg Any

Health restrictions History of demodicosis

History of neoplasia

Serious infection

None History of neoplasia

Renal insuciency

Congestive heart

failure

Diabetes mellitus

Hyperadrenocorticism

Hypertension

Adverse reactions Vomiting

Diarrhea

Nonspecific dermal

masses

Demodicosis

Pyoderma

Vomiting

Diarrhea

Lethargy

Pain at injection site

Rare: Hypersensitivity

eects (urticaria, facial

edema, anaphylaxis)

Vomiting

Diarrhea

Gingival hyperplasia

Hirsutism

Cutaneous

papillomatosis

Drug interactions

Polyuria/polydipsia

Polyphagia

Panting

Obesity

Muscle wasting

Iatrogenic

hyperadrenocorticism

Congestive heart

failure

JAK-STAT, Janus kinase signal transducers and activators of transcription; PO, orally; SC, subcutaneously.

1 Apoquel (oclacitinib tablet). Package insert. Zoetis, 2020.

2 Cytopoint. Package insert. Zoetis, 2015.

3 Atopica (cyclosporine capsules). Package insert. Elanco, 2020.

4 Saridomichelakis MN, Olivry T. An update on the treatment of canine atopic dermatitis. The Vet Jour. 2016;207:29–37.

6 JAAHA | 59:6 Nov/Dec 2023

5. If there is no history of previous skin or ear disease or an uncertain

history, propose observing for recurrence, but also discuss the possi-

bility of a future diagnosis of allergic disease.

If the dog is showing partial or no response while on an appro-

priate antipruritic agent:

1. Repeat cytology.

2. If evidence of bacterial infection is present (Figure 3) and a systemic

antibiotic has already been used:

a. Perform an aerobic bacterial culture and withhold systemic anti-

biotics pending culture and susceptibility results.

b. Choosing a second antibiotic empirically is strongly discouraged

owing to the risk of increasing incidence of antimicrobial drug

resistance. The cost of using the wrong antibiotic can exceed the

cost of culture.

c. If you MUST choose a second antibiotic, be sure to change the

class of antibiotic (e.g., do not change from one beta lactam anti-

biotic to another). See Table 4 for guidance on choosing first-

and second-tier antibiotics.

3. Discuss the owner’s ability to increase the frequency of topical anti-

microbial treatment—often, more intense topical treatment elimi-

nates the need for systemic antibiotics.

4

4. If Malassezia yeasts are identified cytologically from lesioned skin

(Figure 3), then antifungal treatment should be initiated topically

and/or systemically based on clinician discretion. The number of

Malassezia yeasts noted cytologically does not necessarily correlate

with the severity of the disease.

Addressing Malassezia is imperative, especially in individuals with a

hypersensitivity response to these organisms, which in turn worsens

clinical signs.

5

5. If lesions and/or infections have resolved but pruritus persists, the

dog has either atopy or food allergy.

a. Treatment for allergic skin disease is individualized for THIS

dog and THIS client.

b. In general, food allergy is less steroid responsive than atopy.

1

c. If a diet trial is not possible (e.g., the client is not able to comply

or the environment of the dog is not conducive), then symptom-

atic treatment for atopy should be initiated and response to ther-

apy should be assessed.

The guidelines task force acknowledges that a properly

performed diet trial is difficult to conduct and client

compliance can be challenging. The task force recom-

mends considering a consultation with or referral to a

veterinary dermato logist before beginning a diet trial.

Step Six: Diet Trial

Because there are no historical or physical examination findings that

can differentiate atopy from food allergy, a diet trial is an important

step in the diagnostic process. Other than the seasonality associated

with atopy, a higher incidence of gastrointestinal signs in food-allergic

animals, and the possibility that the pruritus may be less steroid

responsive in food-allergic dogs, there are no differences between the

diseases. The previously held observation that an “ears and rears”

pruritic pattern indicates a food allergy is no longer accurate.

1

Serum

tests, saliva tests, and hair tests are of no value in the diagnosis and

management of food allergy.

1,6

FIGURE 3

Cytology of Secondary Bacterial and Yeast Infections.

JAAHA.ORG 7

Diet trials should be conducted for 4–12 wk and a food chal-

lenge performed to confirm the diagnosis of food allergy if there is a

positive response. Recent studies show that a fair number of food-

allergic dogs may respond to strict prescription diet trials in 30 days,

however, 8 weeks may be needed to capture a diagnosis in .90% of

food-allergic dogs, and there is a small subset of dogs that may

require 12 weeks for complete resolution of pruritus.

7,8,9

Antipruritic treatment is frequently needed to give relief during

the initial stage of the diet trial. The guidelines task force considers

glucocorticoids or oclacitinib to be appropriate choices to control

pruritus. If a client is unable to give oral medication during the diet

trial, lokivetmab can be considered as an alternative; however,

because of the long-acting nature of this injection, the diet trial must

be extended more than 60 days to allow for individual variation in

duration of action. The exact length of time a diet trial must be

extended is not known, and for this reason, the task force does not

recommend using lokivetmab during diet trials unless absolutely

necessary—for example, in a young, growing puppy where glucocor-

ticoids are not ideal and oclacitinib is off label.

Diet Choices

Numerous prescription hydrolyzed or novel protein diets are available

in a multitude of formulations, and the option to home cook a highly

limited-ingredient novel protein diet is also available. Although home-

cooked diets potentially offer the strictest formulation, it may be

impractical for many clients in terms of labor and cost of ingredients.

The choice of diet will depend on the dog’s clinical and diet history,

the dog’s dietary preferences, and the owner’s financial constraints.

At present, there is no one-size-fits-all diet that is appropriate for

all patients. Prescription veterinary diets, compared with over-the-

counter (OTC) diets, are less likely to contain unidentified protein

sources

10

and therefore are the only acceptable commercial diet

choices for a true elimination diet trial.

Use of OTC diets should not be recommended

when conducting a diet trial. Ingredients not declared

on the label have been detected in OTC diets, possibly

negating the results of the trial.

11

Howeve r, the guide-

lines task force agrees that an OTC novel protein diet

can be used if financial constraints make other diets

impossible. The client should be warned that an OTC

diet may not provide optimal results and should be

considered a diet change, not a true diet trial.

During the diet trial, monthly oral flavored heartworm and flea

and tick preventives should be avoided. Topical or long-lasting isoxa-

zolines administered at the very beginning of a diet trial along with

topical or injectable heartworm preventives should be considered. It

is imperative to explain that the chosen diet must be the only thing

Recheck skin cytology—if

no indication of yeast

and/or bacterial infection

secondary to the diet

challenge, then the dog

does not have food

allergy. Consider atopy.

Return to the

elimination diet.

May require restarting

antipruritic therapy for 1-2

wk, then discontinuing to

evaluate response

Food allergy is ruled

OUT, consider atopy

Dog has food allergy

Food allergy is ruled

OUT, consider atopy

Did the pruritus return

within 14 days?

Did the pruritus

resolve within 14 days?

YES

Discontinue antipruritic therapy at wk 2–3 of trial,

then recheck and reassess pruritus at 4 wk

Resume antipruritic

therapy for 2-3 wk

and continue the diet

for an additional 4 wk

Perform a food

challenge by

reintroducing the dog’s

previous diet

Is dog pruritic?

YES NO

NO

YES

YES

NO

Discontinue

antipruritic therapy

again while

maintaining strict diet

Is dog pruritic?

NO

FIGURE 4

Assessing Diet Trial Results.

8 JAAHA | 59:6 Nov/Dec 2023

to “pass the lips” of the dog during the 4 to 12 wk trial. This includes

pill pockets, treats, flavored toys, cat food or feces, shared water

bowls, table scraps, etc.

Veterinary technicians can play an important role in

discussing the choice of an appropriate diet with own-

ers, as well as addressing any questions regarding com-

pliance with the trial diet. A follow-up call 2–3wkinto

the diet trial can be beneficial and allows the veteri-

nary team to address any challeng es or client concer ns.

Assessing a Diet Trial

The finalstepinperformingadiettrialistochallengethepatientby

reintroducing the original diet. This is essential in patients that have

responded well to the diet trial and is the sole means of confirming a

diagnosis of food allergy. Misdi agnosi s can result in unnecess ary

expense to the owner (due to long-term use of expensive therapeutic

diets) and the potential for ongoing dermatologic problems (due to

missed diagnosis of seasonal atopy or other pruritic condition).

Figure 4 illustrates the steps of assessing a diet trial.

Remember that a properly performed diet trial is

time-consuming for the veterinarian and client to

manage, and a discussion of a referral to a veteri-

nary dermatologist should be brought up with the

client and considered.

Seasonal or Nonseasonal with Seasonal

Fluctuation (Atopy)

Because atopy is a diagnosis of exclusion, if the dog is on an appropriate

treatment for ectoparasites and a food allergy has not been demon-

strated, then a diagnosis of atopy has been established. Intradermal and

serum allergy testing are NOT used to diagnose atopy. It should only be

used if the client is interested in administering allergy immunotherapy.

Section 2: Treating the Allergic Canine Patient

Top 3 Takeaways:

1. Treating the allergic dog is not one-size-fits-all, and a multimodal

approach often yields the best results.

2. Client education, communication, and compliance is critical in the

success of any treatment plan.

3. If previously successful management protocols stop working, first

perform a thorough history and physical examination and return to

the minimum dermatologic database to determine whether anything

has changed.

Overview

The clinical management of the allergic canine patient is often

viewed as frustrating by veterinarians and clients alike, as there is no

one-size-fits-all treatment. In addition to the need to manage second-

ary infections, inflammatory flares, and individual patient responses,

veterinary teams must consider client compliance, finances, and

other factors like time availability and access to transportation.

Atopic patients need lifelong medical care that will require routine

veterinary visits and an active working relationship with the client.

Tailoring a communication-rich, multimodal approach for each indi-

vidual patient will provide the best path to success.

Flea Allergy

Flea allergy dermatitis is one of the most common causes of pruritus

in canine patients, and successful management relies on a three-

tiered approach.

Step One: Choose the appropriate preventive.

Preventives that have potent adulticide activity should be used. Isoxa-

zolines are now widely considered the gold standard in prevention

and are recommended for initial consideration. It has been demon-

strated in recent years that dogs with flea allergy dermatitis may be

successfully managed with the routine administration of an oral iso-

xazoline.

12

The effectiveness of the preventive chosen is closely tied

to accurate application of the product.

Step Two: Use the preventive year-round in all

in-contact animals.

Step Three: Treat the environment in severe

infestation situations.

Food Allergy

Avoiding all offending allergens, based on the diet challenge trials, is

the goal for patients and clients. Here the client has two options: a

veterinary prescription diet or OTC food.

An unfortunate consequence of maintaining a patient on a pre-

scription diet is the potential for backorders. Consider other prescrip-

tion diets that avoid the offending allergen or have similar ingredients.

Pet food companies can provide excellent technical support and may

have additional recommendations. A helpful tip is to have clients keep

extra dog food bags on hand to avoid temporary backorder issues.

For some patients, control may be maintained by feeding an OTC

diet that does not claim to contain the offending allergen. In a small sub-

set of dogs, however, their severe sensitivity prohibits the use of OTC

diets because of potential contamination with unlabeled proteins.

10,13

If a flare occurs in a patient on an OTC diet, inquire whether

they were fed from a new bag of food as the formulation may have

changed or the batch may contain unlabeled proteins. Investigate

whether they are now displaying clinical signs of atopy in conjunc-

tion with food allergy and consider ectoparasites, as they are the

leading cause for acute-onset pruritus.

JAAHA.ORG 9

Atopy

Initial Management

When choosing a management protocol, the clinician must take into

consideration the level of inflammation and pruritus present and

whether any secondary infections are present. If a patient is 10/10

pruritic with severely inflamed skin, a glucocorticoid may offer an effec-

tive initial treatment and a short course may effectively manage a single

atopic episode. Many veterinary dermatologists would recommend the

use of glucocorticoids over oclacitinib in severely inflamed skin; how-

ever, there is evidence to show that oclacitinib can have the same anti-

inflammatory benefits as prednisolone in certain cases.

14

Lokivetmab

maybeanappropriatechoicewheninflammation is less severe.

For mild to moderate inflammation and pruritus, oclacitinib

and/or lokivetmab (see Table 1 and Table 2) may be administered.

Multiple factors should be considered when choosing one of these

drugs as neither medication is 100% effective, and there is significan t

variation in individual patient response.

15,16

Oclacitinib is more effec-

tive in some patients, and lokivetmab is more effective in others.

17

If the patient is presenting for extremely mild clinical signs, an

antihistamine (see Table 3) trial may be appropriate; however, it is

imperative to remember that antihistamines are best used as preven-

tive medicine, do not perform well as monotherapy, and are not

effective in treating moderate to severe inflammation or pruritus.

18,19

Long-term Management

A multimodal approach can promote successful long-term manage-

ment, but it will take patience while assessing which option works

for each patient.

If adequate control of clinical signs cannot be

achieved by the third veterinary visit, then referral

to a veterinary dermatologist should be presented

as an option to the owner

49

to provide more effec-

tive treatment and less cost to the client in the long

run. Referral could be discussed even earlier, but

this may not always be necessary. Availability to be

evaluated by a veterinary dermatologist could be

markedly delayed in certain geographic areas, in

which case more acute management by a general

practitioner would be needed.

If the veterinary team moves forward with treatment, the fol-

lowing steps are recommended.

1. Continue antipruritic/anti-inflammatory therapy and use routinely

in a preventive manner. If oclacitinib and lokivetmab have been

found ineffective, cyclosporine may be considered, with the under-

standing that it will take 4–6 wk to be maximally effective.

19

Some patients are glucocorticoid-responsive-only

and/or some clients cannot afford other treat-

ments; therefore, chronic management with gluco-

corticoids may be appropriate. A thorough discussion

of the potential long-term side effects and recom-

mended monitoring must take place.

2. Consider adjunctive therapies such as veterinary-formulated essen-

tial fatty acid supplementation, specially formulated dermatologic

diets, nutraceuticals, palmitoylethanolamide, probiotics, and pro-

ducts aimed at improving epidermal barrier dysfunction. These are

all excellent options to consider in atopic patients.

15

3. Topical therapy: routine bathing using shampoos with moisturizing

factors (i.e., fatty acids, oatmeal, ceramides, and lipids) can be help-

ful as adjunctive therapy. Particularly with dogs experiencing recur-

rent bacterial pyoderma and/or Malassezia dermatitis, anti-infective

shampoos, mousses, or sprays can be used routinely to help reduce

the recurrence of secondary infections.

4. Allergen-specific immunotherapy (ASIT) is a safe, drug-free treat-

ment that is effective in 50–100% of canine patients.

21

Clinical

benefit may not appear for up to a year, and routine antipruritic/

anti-inflammatory management will be required in the interim.

19

Successful ASIT protocols again require diligent, educated clients

who recognize that it is not a quick fix.

For allergy testing and ASIT management, referral

to a veterinary dermatologist is highly recommended

as tailoring individual protocols increases positive

response rates.

22

The preferred method of testing,

whether intradermal allergy testing or serum allergy

testing, is highly controversial and has not yet been

established in the literature.

23

Injectable immuno-

therapy is considered the standard; however, sublin-

gual immunotherapy has also been shown to be

effective.

24,25

Management of Acute Flares

All atopic dogs will experience allergic flares regardless of how well

managedtheyare.Whenaflare occurs, collect a thorough history

and a minimum dermatologic database to determine whether there

have been any changes in the patient’s lifestyle. Look for evidence of

ectoparasitism or secondary infections. If the flare is mild and sec-

ondary issues have been identified, managing the secondary issues

should resolve the increased pruritus.

If the inflammatory flare is severe, the addition of a short

course of glucocorti coids may be ben eficial in regaining control.

If glucocorticoids are contraindicated, administering twice-daily

oclacitinib for a limited time (e.g., up to 14 days) or adding loki-

vetmab may be appropria te. Cycl osporine is not appropriate for

an acute flare.

Acute Flare Factors

•

Secondary infections

•

Ectoparasites (fleas/mites)

•

Environmental/seasonal changes

•

Food challenges (holidays!)

10 JAAHA | 59:6 Nov/Dec 2023

TABLE 2

Acute Flare and Long-term Management Therapies in Dogs

JAAHA.ORG 11

Considerations in Treating Secondary Infections

When superficial bacterial folliculitis (SBF) is identified, there are

three guidelines to follow: correct antibiotic, correct dose, and cor-

rect duration.

4

Table 4 provides a tiered approach to appropriate

antibiotic choices including recommended doses for managing SBF.

The golden rule for duration of antibiotic therapy is 7 days past clini-

cal and cytologic resolution.

26

As such, the current recommended

course for oral antibiotics in treating SBF is typically 21 days.

Topical therapy is an integral part of managing SBF, and many

infections will resolve with topical therapy alone.

27,28

As this requires

advanced client compliance, prescribing more user-friendly formulations

(spot-ons, sprays, or mousses) may encourage more effective usage.

Topical antimicrobial therapy also acts as an excellent adjunctive

therapy to oral antibiotics.

TABLE 3

Oral Antihistamine Doses for Dogs

Drug Name Dose

Hydroxyzine 2 mg/kg q 12 hr

1

Cetirizine 1–2 mg/kg q 24 hr

1

Chlorpheniramine 0.4 mg/kg q 12 hr

2

Cyproheptadine 0.3–2 mg/kg q 12 hr

2

Clemastine 0.05–1 mg/kg q 12 hr

2

Loratadine 1 mg/kg q 12 hr

2

Fexofenadine 5–15 mg/kg q 24 hr

3

Amitriptyline 1–2 mg/kg q 12 hr

2

Diphenhydramine 2–3 mg/kg q 12 hr

2

4

1 Bizikova P, Papich MG, Olivry T. Hydroxyzine and cetirizine

pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics after oral and

intravenous administration of hydroxyzine to healthy dogs. Vet

Dermatol. 2008;19:348–57.

2

Muller & Kirk’s Small Animal

Dermatology. 7th ed. St. Louis:Elsevier;2013.

3

antihistamine fexofenadine versus methylprednisolone in the

treatment of atopic dermatitis in dogs. Slov Vet Res. 2009;46:5–12.

4

and cetirizine on immediate and late-phase cutaneous allergic

reactions in healthy dogs: a randomized, double-blinded

crossover study. Vet Dermatol. 2020;31:256–e58.

TABLE 4

Antimicrobials for Skin Infections in Dogs

1

*

12 JAAHA | 59:6 Nov/Dec 2023

Malassezia dermatitis is a common flare factor and may dra-

matically increase pruritus in atopic dogs. In many cases, appropriate

treatment for Malassezia significantly increases the effectiveness of

antipruritic/anti-inflammatory therapy. Topical treatment for Malas-

sezia may be useful, however, some cases of deep or chronic Malasse-

zia dermatitis (such as Malassezia in the claw folds or in severely

lichenified skin) necessitate oral antifun gal therapy with

ketoconazole, fluconazole, itraconazole, or terbinafine (Table 5). The

golden rule of 7 days past clinical and cytologi c resolution applies

here, too.

Section 3: Diagnosing the Feline Patient

Top 3 Takeaways:

1. Cats, unlike dogs, have a more varied clinical presentation of aller-

gic dermatitis, including scratching, overgrooming, and several

cutaneous inflammatory reaction patterns.

2. Treating all pruritic cats for fleas/mites is not only a potentially

important therapeutic measure but also a key diagnostic step on the

path to determining the primary cause of pruritus.

3. There are no accurate allergy tests for diagnosing feline atopic skin

syndrome (environmental allergies) in cats. This diagnosis is deter-

mined through diligently ruling out all other causes of pruritus.

Overview

Compared with dogs, the pathogenesis of skin diseases in cats is not

as well understood. Recently, there has been a resurgence in investi-

gation for this species and attempts to clarify and classify the feline

allergic profile.

Feline atopic syndrome has been proposed as the umbrella

nomenclature describing allergic dermatitis involving environmental

allergens, food allergy (gastrointestinal manifestation), and allergic

asthmas (respiratory disease) often associated with immunoglobulin

E antibodies. Feline atopic skin syndrome (FASS) refers to the entity

associated with inflammatory and pruritic allergic skin disease from

environmental allergens.

29

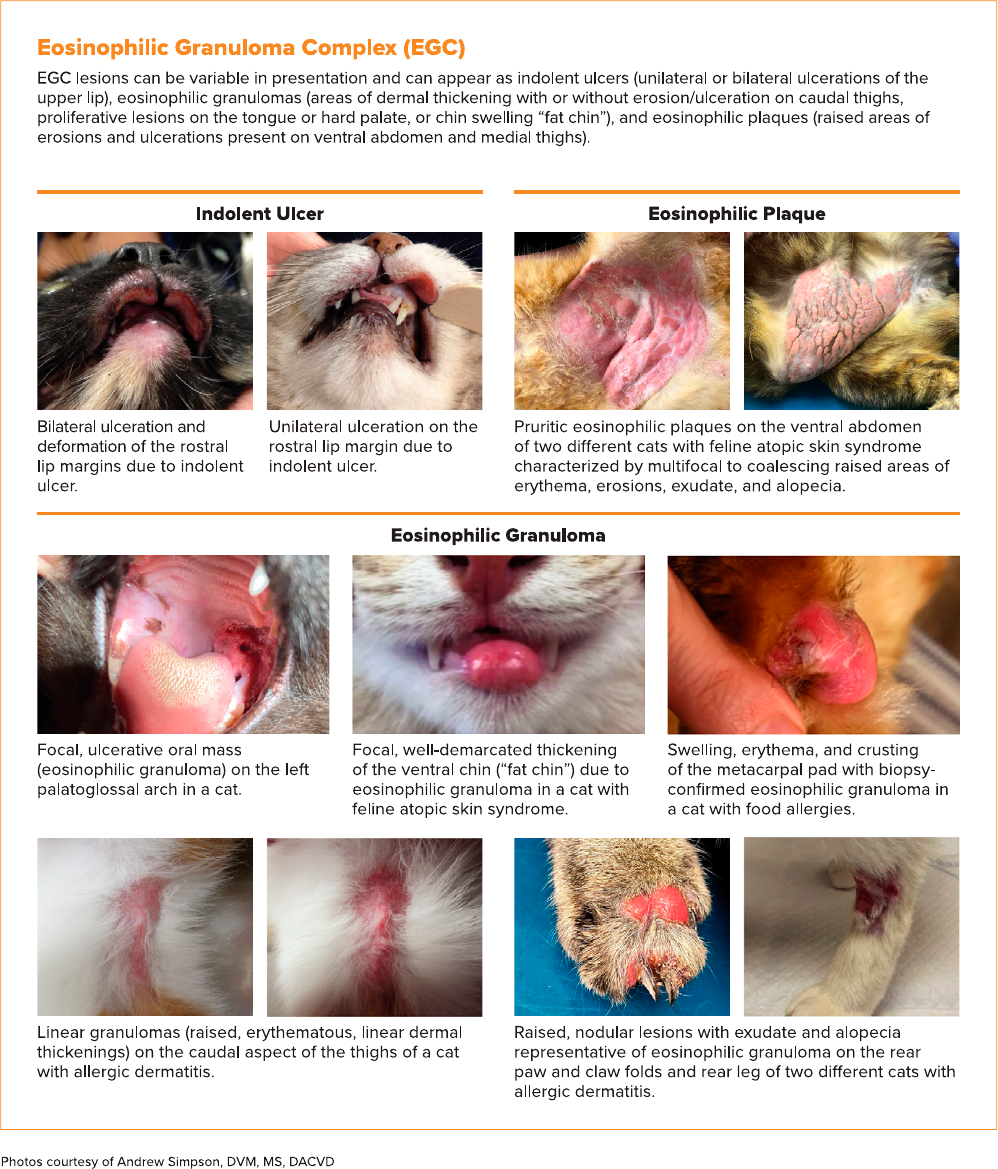

Presentation of the Feline Patient

Four distinct clinical patterns of allergic dermatitis have been

described in the cat: miliary dermatitis, head and neck pruritus, self-

induced alopecia, and eosinophilic granuloma complex (eosinophilic

plaques, granulomas, and indolent ulcers) (see Figure 5). Pruritus,

from mild to severe, is typically present in cats with allergic dermatitis,

whether due to food allergy, flea allergy, and/or FASS (environmental

allergies). Exceptions include indolent ulcers or eosinophilic granulo-

mas, which can occur without pruritus.

30

None of the feline cutaneous reaction patterns are pathogno-

monic for any particular pruritic disease, emphasizing the need to

perform a thorough diagnostic workup,

31

including an accurate clini-

cal history, dermatologic physical examination, and a minimum der-

matologic database. Atypical or non–treatment-responsive lesions

mayrequireaskinbiopsyfordefinitive diagnosis.

Step One: Clinical History and Dermatologic Physical

Examination

Clinical History

When inquiring about the presence and intensity of pruritus in

the cat, it is important to educate the client that feline pruritus can

manifest as scratching (head, neck, ears) with the hind paws and/or

overgrooming (licking/biting/chewing) of specific areas such as the

ventral abdomen, lumbar region, tail, and along the front and hind

limbs. In addition, clients should know that some cats are “closet

groomers” and may engage in overgrooming when clients are not

directly supervising them. A trichogram demonstrating sharply bro-

ken hair shafts is an excellent way to confirm self-trauma as the

cause of hair loss. A validated scoring method for pruritus has been

published recently for cats,

30

which provides the client with detailed

direction on ranking both scratching and licking behaviors by mark-

ing responses along a series of descriptions. This should be used at

the initial appointment and then at each subsequent appointment

after starting ectoparasite treatment, an elimination diet trial, courses

of glucocorticoids, or long-term therapies for FASS (i.e., allergy

immunotherapy or cyclosporine).

Having technicians take the history is an excellent

way for them to build client trust and relationships

that can carry through treatment follow-ups, client

education, and ongoing control measures.

TABLE 5

Oral Antifungal Medication Doses for Dogs

JAAHA.ORG 13

FIGURE 5

Clinical Presentation of the Pruritic Feline Patient.

14 JAAHA | 59:6 Nov/Dec 2023

FIGURE 5

Continued.

JAAHA.ORG 15

Key Clinical History Questions

1. At what age did the pruritus start?

2. Is it seasonal?

3. Are other cats or dogs in the house itchy?

4. How much time is spent indoors versus outdoors?

5. Was the cat recently housed in a shelter/cattery/boarding facility?

6. Has there been any exposure to new or stray cats?

7. How often is ectoparasite control applied?

8. Has there been a response to other treatments, including antibiotics

or antipruritic medications?

9. What previous diagnostic tests have been performed?

Dermatologic Physical Examination

Evaluation should include the most commonly affected areas includ-

ing the head, neck, and ventral abdomen; however, any area of

haired skin could potentially be involved, such as along the dorsum,

sternum, axillae, medial thighs, forelimbs/hindlimbs, paws, perineum,

and tail.

31

The oral cavity should be examined to look for granulomas

of the tongue/palate and indolent ulcers of the upper lip. Flea comb-

ing is a crucial part of the examination to identify live fleas and/or

flea dirt to support a diagnosis of a flea infestation or allergy.

Otitis externa can occur in 20% of cats with feline atopic skin

syndrome,

31,32

but it can also occur in cats with food allergy. Evalua-

tion of the pinnae and otoscopic examination of the ear canals is an

integral part of the complete dermatologic examination.

Step Two: Minimum Dermatologic Database

The minimum dermatologic database should be collected based on

reaction patterns (Figure 6).

Cytology of skin and ear (if evidence of ear disease is present).

Superficial bacterial skin infections and Malassezia infections can be

present with all cutaneous reaction patterns, and thus, all skin

lesions on the cat should be sampled for secondary infection, placing

this diagnostic higher on the priority list. The exception to this

rule would be self-induced alopecia without overt evidence of cuta-

neous inflammation, as alopecia alone is not as likely to harbor

infection.

Superficial and deep skin scrapings. Ideal in all cases of pruritic

skin disease in cats to potentially provide a definitive diagnosis.

When broad-spectrum ectoparasiticides are used (i.e., isoxazolines),

keep in mind that treatment failures could still occur.

6 DTM culture. Considering that pruritus is typically minimal to

absent in most cases of dermatophytosis,

33

performing a fungal

culture (DTM) and/or dermatophyte polymerase chain reaction

test may not be necessary in all cases of cats with cutaneous reac-

tion patterns. This reflects the majority opinion of the guidelines

task force; however, not all members agreed on the overall ranking

of screening for dermatophytosis. One task force member felt that

although dermatophytosis is not t ypically pruritic (or at least

not severely), it should be ranked higher on the differe ntial list

because of its likelihoo d of occurrence. Consider ation of dermato-

phytosis may rank higher on the differential list under certain

circum stances, including indoor/outdoor cats, recently adopted

kittens, older immunocompromised cats, and Persians and other

long-h aired felines. In some cases, such as miliary d ermatitis and

self-induced alopec ia, DTM 6 de rmatophyte polymerase chain

reaction test may be more highly considered if parasites have been

ruled out.

Skin scrapings and otic preparations for mites

could be prioritized lower on the list with cost-

concerned clients, as pruritic mites are already

likely being treated if isoxazolines have been

prescribed.

Step Three: Treat Pruritus During the

Diagnostic Period

Many itchy cats require glucocorticoids because of their rapid and

reliable benefits for immediate treatment, especially when moder-

ate to severe pruritus and/or inflammatory lesions are present.

34

Antihistamines are not as reliable at controlling itch

35

and do not

have enough anti-inflammatory properties to reduce severely

inflamed lesions. Cyclosporine, although effective for long-term

treatment, does not typically provide immediate relief from

pruritus.

It is recommended to consider oral glucocorticoids (predniso-

lone 2 mg/kg/day, methylprednisolone 0.8–1.5 mg/kg/day,

34

or dexa-

methasone 0.2 mg/kg/day

26

tapered over a 3 wk period) rather than

injectable repositol glucocorticoids, given the inability to rapidly

withdraw the medication in the event of side effects (e.g., congestive

heart failure, diabetes, and skin fragility).

Step Four: Treat Ectoparasites and Secondary

Infections

Ectoparasite Treatment

It is essential to rule out external parasites (i.e., fleas and mites) in all

cases of feline pruritus with reliable parasite control measures. Dis-

cussion of all available flea treatment products is beyond the scope of

these guidelines; however, the guidelines task force generally recom-

mends the use of isoxazolines (fluralaner, sarolaner, and lotilaner)

owing to their relatively rapid flea adulticidal properties in addition

to off-label broad-spectrum ectoparasite coverage (i.e., Demodex cati,

Demodex gatoi,andOtodectes).

36–38

When reviewing the known or suspected clinical picture with

clients, it is important to discuss therapy durations. Be candid that

treating mites takes 6–8 wk on average, whereas a flea infestation

takes closer to 3 mo to treat under ideal conditions. Openly discuss-

ing client constraints (e.g., time, ability to comply, and finances) in

initial appointments will inform treatment choices and expectations

for the veterinary team and clients.

16 JAAHA | 59:6 Nov/Dec 2023

Complete response

after stopping

antipruritic medication

Assess for food allergy + maintain year-round flea preventives

FASS

STEP 5: Recheck/Assess Response to Antiparasitic/Antipruritic Treatment

STEP 4: Treat Ectoparasites and Secondary Infections

STEP 3: Treat Pruritus: oral glucocorticoids (prednisolone or methylprednisolone)

Flea allergy/mites or

seasonal FASS:

maintain year-round

flea preventives

Nonseasonal Seasonal

Food allergy

Consider food allergy concurrent

with FASS. Continue diet trial

while treating for FASS

Treat for FASS,

recheck MDB

Partial or no response after stopping antipruritic medication

Parasite treatment

Cytology

DTM

Skin scrape

Parasite treatment

DTM

Skin scrape

Parasite treatment

Ear cytology/mite treatment

Cytology

Skin scrape

DTM

Cytology

Parasite treatment

Presentation of cat:

Skin lesions +/- pruritus

STEP 1: Clinical History and

Dermatologic Physical Examination

Miliary Dermatitis Self-Induced Alopecia Head/Neck Pruritus Eosinophilic Lesions

STEP 2: MDB

Collect MDB based on reaction patterns (in order of priority)

DTM, dermatophyte test medium; FASS,

feline atopic skin syndrome; MDB, minimum

dermatologic database.

STEP 6: Diet Trial

Complete response Partial response No response

Pruritus when diet

is challenged

FIGURE 6

Diagnosing Allergic Skin Disease in the Feline Patient.

JAAHA.ORG 17

Treat Secondary Infections

Superficial skin cytology is the diagnostic method of choice to iden-

tify the presence of secondary infection with either bacteria or Malas-

sezia and can be performed using a microscope slide (for a direct

impression smear of exudative lesions) and acetate tape (for scaling,

crusting, and erythema).

Treatment for bacterial infection (amoxicillin-clavulanic acid

12.5–20 mg/kg orally twice daily; clindamycin 11–33 mg/kg orally

once daily; cefovecin 8 mg/kg subcutaneously) should be based on

the presence of degenerate neutrophils with cocci-shaped bacteria.

39

Bacterial culture and susceptibility testing may be needed in more

complicated cases involving rod-shaped bacteria. Finding more than

one Malassezia per high-power field suggests yeast overgrowth

40

and

may warrant systemic therapy.

41

For Malassezia dermatitis, itracon-

azole, fluconazole, or terbinafine should be selected (Table 9). Keto-

conazole may cause severe hepatotoxicity in cats.

42

Although topical antimicrobial therapies are ideal to reduce the

overall exposure to systemic antibiotics, the grooming behavior of

cats and their decreased tolerance for topical applications often limits

their use.

If diagnostics cannot be performed because of client

financial constraints, then it would be most advan-

tageous to use a broad-spectrum external parasite

treatment in addition to a tapering course of oral

glucocorticoids.

Step Five: Recheck, Assess Response to

Antiparasitic/Antipruritic Therapy

In flea-endemic areas, consistent flea prevention should be continued

in all cats year-round regardless of their flea history to reduce the

possible burden of flea allergy leading to worsening dermatitis and

pruritus. If there is no improvement or only partial improvement of

pruritus and clinical lesions after ectoparasiticide treatment and

addressing secondary infections, then other causes of pruritus should

be investigated. A skin biopsy is recommended in cases with atypical

lesions to rule out other pruritic dermatoses (e.g., pemphigus folia-

ceus), especially in cases of crusting dermatitis without cytologic evi-

dence of bacterial or yeast. With nonseasonal pruritus, a restrictive

diet trial should be pursued to rule out food allergies.

Step Six: Diet Trial

Food allergies in cats can only be diagnosed with an elimination diet

trial, by feeding either a hydrolyzed or a novel protein diet.

43–45

Definitive diagnosis is ultimately confirmed if the pruritus and/or

skin lesions return after challenging the cat with the previous diet

and then resolve again once returning to the restrictive diet. It is

recommended to conduct the elimination diet trial for 8 wk, as 90%

of food-allergic cats resolve their clinical signs by this time point,

whereas 50% of feline food-a llergic cases resolve at 4 wk.

46

Use of OTC diets should not be recommended

when conducting a diet trial in cats. Ingredients

not declared on the label (e.g., chicken) have been

detected in up to 82% of OTC feline diets,

47,48

pos-

sibly negating the results of the trial. However, the

guidelines task force agrees that an OTC novel pro-

tein diet can be used if financial constraints make

other diets impossible. The client should be warned

that an OTC diet may not provide optimal results

and should be considered a diet change, not a true

diet trial.

Systemic glucocorticoids can be withdrawn at the 3 wk point of

a diet trial and/or parasite treatment trial and again at the 6 wk point

to assess response to diet alone.

Feline Atopic Skin Syndrome Diagnosis

FASS can only be diagnosed based on compatible history and clini-

cal signs and by ruling out all other diseases that can look similar

to this disease (i.e., flea allergy, food allergy, external parasites, bac-

terial skin infection, and dermatophytosis). Up to 25–30% of cats

with FASS will exhibit seasonal patterns,

32

which supports a diag-

nosis of environmental allergies without the need for an elimina-

tion diet trial, if external parasites and secondary skin infections

have been treated and/or ruled out. Otherwise, lack of response to

a restrictive diet trial would indicate FASS in the nonseasonal pru-

ritic cat.

Once a diagnosis of FASS has been achieved by pro-

cess of elimination, intradermal or serum allergy test-

ing by a veterinary dermatologist is then a useful

tool to identify which specific environmental allergens

should be included in allergy immunotherapy.

Superficial bacterial skin infection due to Staphylococcus spp. on

the lateral neck of a cat. Note the alopecia, exudate, crusting, ery-

thema, and erosions.

Credit: Photo courtesy of Andrew Simpson, DVM, MS, DACVD

18 JAAHA | 59:6 Nov/Dec 2023

Section 4: Managing Feline Chronic

Allergic Conditions

Top 3 Takeaways:

1. Ectoparasites and infections need to be ruled in/out and addressed

before treating allergic skin disease in cats.

2. Flea allergy dermatitis is the most common allergic skin disease; dil-

igent adulticidal flea prevention is key in any pruritic feline patient

as this can be a complicating concurrent factor.

3. FASS has different management considerations compared with

canine atopic dermatitis; partnership with a veterinary dermatolo-

gist can be beneficial for these patients.

Overview

Identifying the cause(s) of an allergic condition can be a long, often

frustrating process of trial and error for both clients and veterinary

staff. Although ultimately discovering the source brings relief, this is

actually just the beginning of another stage that will last the cat’s

lifetime—that of managing a chronic condition. Before launching

into what will be required next, however, pausing to congratulate the

client for seeing the diagnosis process through speaks volumes about a

practice’s compassion and desire to cultivate long-lasting relationships.

Treating Flea Allergy

Flea allergy dermatitis is the most common allergic skin disease, seen

solely or concurrently with other allergic conditions. Diligent adulti-

cidal flea prevention must continue long term and consists of the

following considerations:

1. Use FDA-approved products for cats.

2. Recommend isoxazoline medications for broad coverage (fluralaner,

sarolaner, lotilaner, 6 selamectin or moxidectin).

3. Treat for the proper duration and response for fleas versus mites.

TABLE 6

Antipruritic and Anti-inflammatory Medications for Cats

JAAHA.ORG 19

4. If there are multiple cats or the client has difficulty medicating, con-

sider imidacloprid/flumethrin collars.

5. Ensure other animals are treated and on year-round prevention as

well.

6. Consider environmental treatment.

7. Educate clients on the life cycle of fleas, including the time it takes

to see treatment response.

8. Symptomatic antipruritic therapy:

Prednisolone 2 mg/kg/day per os (PO) tapered over 3 wk

Methylprednisolone 0.8–1.5 mg/kg/day PO tapered over 3 wk

Dexamethasone 0.2 mg/kg/day PO tapered over 3 wk

Technicians can discuss treatment of other pets in

the households, explain parasite life cycles, and rein-

force the importance of year-round prevention with

clients.

Treating Food Allergy

Food allergy (at least anecdotally) seems to be more common in cats

than dogs. For cats, palatability of a diet and securing the preferred

formulation (e.g., dry only versus wet) are important considerations,

especially if the patient is a picky eater. Ideally, a prescription veteri-

nary diet should be fed long term with either a novel protein diet

(e.g., rabbit, kangaroo, or alligator) or a hydrolyzed diet (hydrolyzed

soy, hydrolyzed fish, or hydrolyzed poultry feather). If a specificaller-

gen is identi fied, an OTC diet that does not contain this allergen may

be an effective choice for long-term management. Once an appropri-

ate diet has been identified, clients must stick to the regimen and

understand this will be a commitment for the rest of the cat’slife.

During client education, technicians or members of the veteri-

nary team should advise clients to plan for possible shortages or

backorders of special diets. Keeping extra bags or cans of food on

hand is one strategy. Considering different brands with similar or

identical ingredients is another. Choosing a home-cooked diet in

consultation with a veterinary nutritionist is a third strategy, but it

should be done with extreme caution to account for the specific

nutritional needs of cats.

Treating Feline Atopic Skin Syndrome

A diagnosis of FASS is an excellent juncture in treatment to consider

referral to a veterinary dermatologist if this has not occurred already.

Finding the proper therapeutic regimen for a feline patient and client

can be challenging, and “tinkering” with options that do not provide

sufficient improvement tends to lead to client frustration and poten-

tial loss of trust.

49

Even for clients with cost concerns, a veterinary

dermatologist can provide more targeted treatment to bring the

patient relief. Moreover, there may be time and cost savings in the

long run with more targeted treatments.

If referral is not possible or desired, establishing a baseline level

of pruritus at this point is helpful to assess response to various

therapeutic interventions. Because glucocorticoids tend to provide

relief for most allergic cats, they should be considered as a first test

intervention to determine the degree of improvement. If FASS is sea-

sonal,theymaybeanoptionforcontinuedmanagement.

Once pruritus surpasses 6 out of 12 mo in a given year, alterna-

tive options should be discussed with the clients (see Table 7).

Cyclosporine is a labeled treatment for feline allergy and comes

in liquid form; however, its palatability is questionable, and many

owners struggle with administration. It takes time to reach therapeu-

tic levels (4–6 wk), but at that point, most cats can have the fre-

quency decreased to every other day (or possibly less). This should

not be recommended for cats that go outside owing to the increased

risk of infectious disease exposure that may be fatal on this medica-

tion (e.g., toxoplasmosis). Cats on this medication should be fed a

cooked diet and maintained on effective internal and external para-

site control measures.

Oclacitinib is not labeled for cats and has not been thoroughly

assessed in this species with regard to long-term safety and dosing.

The task force does not recommend the use of oclacitinib in cats at

this time.

Lokivetmab should not be used in cats; this caninized monoclonal

antibody can potentially be fatal if administered to a non-dog species.

Immunotherapy canbeanexcellentoptionforcatswithFASS

as this species tends to respond more favorably than not.

35

Keep in

mind that allergy tests, both serum and intradermal, do not diagnose

allergy but rather support the clinical diagnosis and aid in immuno-

therapy formulation; they should not be used as “allergic or not”

diagnostics, as they can be positive in animals with no clinical signs

of allergy. Both injectable and sublingual immunotherapy may be

considered depending on client and patient preference. Most owners

elect injections first due to ease of administration, but the oral option

is also effective in cats.

Opting for immunotherapy is another treatment

juncture where veterinary dermatologists may be

more adept at the intricacies of testing, formula-

tions, and making appropriate adjustments.

Alternative or adjunct therapies to consider in the allergic

feline include the following:

Antihistamines. Can be helpful in cats with concurrent upper respi-

ratory manifestation of allergy, but they do not provide much pruri-

tus relief (Table 8).

Nutraceuticals (e.g., ultra-micronized palmitoylethanolamide and essen-

tial fatty acids). These can be administered separately as supplements,

or some clients may appreciate the benefitfroma“skin support” diet

that includes these ingredients as opposed to another oral therapy.

Topical skin barrier support (e.g., fatty acid/essential oil spot-on

formulations). The benefits of these interventions to allergic cats are

somewhat uncertain owing to the lack of information supporting

the impact of barrier dysfunction in feline allergy. They may at least

20 JAAHA | 59:6 Nov/Dec 2023

be good options for mildly affected cats or as adjunct therapy to

reduce other medication requirements.

Treating Flares

As with dogs, even the best-managed allergic cat can experience

episodes of pruritic flare. It is imperative to reassess the presence

of ectoparasites and secondary bacterial and yeast infections in

this situation, as these remain common complications in the face

of allergy. Additionally, remind owners that treatment does not

just stop working once it has been determined to be beneficial;

rather, the cat may need a bit of extra support during these

episodes.

To provide antipruritic and anti-inflammatory benefit during

acute flares, a tapering course of systemic glucocorticoids should be

considered, such as prednisolone (2 mg/kg PO q 24 hr), methylpred-

nisolone (0.8–1.5 mg/kg PO q 24 hr), or dexamethasone (0.2 mg/kg

PO q 24 hr). In addition, in cases in which cats have been receiving

lower-dose cyclosporine (i.e., every-other-day dosing or twice-weekly

dosing), a temporary increase to once-daily dosing can be recom-

mended for 3–4wk.

Section 5: Otitis Externa

Top 3 Takeaways:

1. Recurrent otitis externa is commonly caused by underlying allergic

disease, and in some patients, it may be the only clinical manifesta-

tion of allergy.

2. Cytology should be performed in every case of otitis externa.

3. The goal of short-term treatment is to reduce inflammation and

treat secondary infection (where present), while long-term manage-

ment aims to control inflammation and maintain ear health.

TABLE 7

Acute Flare and Long-term Management Therapies in Cats

JAAHA.ORG 21

Overview

Allergic otitis externa (AOE) is a common manifestation of allergy in

animals and in some cases is the only clinical sign. AOE is an inflam-

matory condition of the ear and should not be confused with

infection—which commonly occurs secondary to AOE. Although it

is important to identify and treat secondary infections, identification

of the primary (underlying) cause of otitis externa is critical to the

prevention of recurrent otitis. More than half of dogs and 20% of

cats with allergies have AOE.

50–52

Other primary causes of otitis

externa include parasites, foreign body, neoplasia, endocrinopathy,

andkeratinizationdisordersandshouldberuledoutinevery

case.

26,51

AOE occurs frequently in patients with atopic dermatitis

andfoodallergybutisnotafeatureofflea allergy dermatitis.

Clinical Presentation

Most cases of AOE present as bilateral ear disease—although disease

severity may differ between ears. Otic pruritus manifests as head

shaking, scratching at the ears, and rubbing the face/head. Clinical

signs of AOE include pruritus, pain, erythema, ceruminous (waxy)

exudate, periauricular alopecia, and excoriation. When secondary

infection is present, otic exudate (6 malodorous), crusting/scaling,

erosions, and asymmetric ear carriage may also oc cur. Otitis

media/interna should be suspected in animals presenting with hear-

ing loss, head tilt, vestibular disturbances, Horner’ssyndrome,

and/or temporomandibular joint pain.

Diagnosis

The importance of a thorough evaluation of the ears in any patient

presenting with dermatologic disease cannot be overemphasized. This

includes examination of the periauricular region and pinna, palpa-

tion of the canals, and otoscopic examination. Pliability of the carti-

laginous structures of the ear canals provide clues to pathologic

changes that can result from chronic inflammation, which can ulti-

mately lead to calcification. Otoscopy not only is important for

examination of deeper ear structures but also helps to rule out most

other primary causes of otitis externa. Chronic inflammation can

lead to ceruminous gland hyperplasia within the ear canals causing a

cobblestone-like appearance.

51

Stenosis of the ear canals occurs

because of edema and inflammation and/or pathologic changes to

the ear over time.

Secondary infection is common in animals with AOE. Altera-

tions of the skin’s natural flora have been demonstrated in dogs with

TABLE 8

Oral Antihistamine Doses for Cats

Drug Name Dose

Hydroxyzine 5–10 mg/cat (NOT mg/kg) q 12 hr

1

Cetirizine

5–10 mg/cat (NOT mg/kg) q 24 hr

2

Chlorpheniramine

2–4 mg/cat (NOT mg/kg) q 12 hr

2

Cyproheptadine

2 mg/cat (NOT mg/kg) q 12 hr

2

Clemastine

0.68 mg/cat (NOT mg/kg) q 12 hr

2

Loratadine

2.5–5 mg/cat (NOT mg/kg) PO q 24 hr

1

Fexofenadine 30–60 mg/cat (NOT mg/kg) PO q 24 hr

3

Amitriptyline 2.5–7.5 mg/cat PO (NOT mg/kg) q 12 hr

1

Diphenhydramine 2–3 mg/kg q 12 hr

2

1 Plumb DC. Plumb’s Veterinary Drug Handbook. 9th ed. Wiley-Blackwell;2018.

2 Muller & Kirk’s Small Animal Dermatology. 7th ed.

St. Louis:Elsevier;2013.

3 Diesel A. Feline allergy: symptomatic treatments. In: Noli C, Foster A, Rosenkrantz W,

Miller WH, Grin GE, Campbell KL.

eds. Veterinary Allergy. West Sussex (UK):John Wiley and Sons;2014.

TABLE 9

Oral Antifungal Medication Doses for Cats

1,2

Drug Name Dose

Ketoconazole Contraindicated—causes

severe hepatotoxicity

2

Fluconazole 5–10 mg/kg q 24 hr

Itraconazole 5 mg/kg q 24 hr

Terbinafine 30–40 mg/kg q 24 hr

1 Muller & Kirk’s

Small Animal Dermatology. 7th ed.

St. Louis:Elsevier;2013.

2 Plumb DC.

Miller WH, Grin GE, Campbell KL.

Plumb’s Veterinary Drug Handbook.

9th ed. Wiley-Blackwell;2018.

22 JAAHA | 59:6 Nov/Dec 2023

atopic dermatitis, and a similar dysbiosis has also been observed

within the ear canals of atopic dogs having increased amounts of

Staphylococcus spp. relative to normal dogs.

53

Inflammation causes

changes to the ear canal microenvironment, altering the bacterial

population and creating an ideal environment for yeast (Malassezia

spp.) overgrowth.

51

Therefore, it is imperative that ear cytology be

performed in every case of AOE. Diagnostic evaluation should

include both a stained, dry-mounted sample to assess for microbial

infection and an unstained, mineral oil wet mount to rule out otic

ectoparasites. This is of particular importance in cats because of the

prevalence of Otodectes in this species.

Training technicians to obtain an d interpret ear

cytology facilitates increased efficiency when seeing

appointments.

Treatment

Topical therapy should always be guided by cytologic findings. In

cases with abundant exudate, an in-clinic ear flush should be per-

formed to aid in the removal of exudate and facilitate a more thor-

ough otoscopic examination. Caution should be exercised in cases of

a ruptured tympanic membrane, with careful selection of antimicro-

bial agents and cleaning solutions that are safe for use in the middle

ear. Discussion of specific products and ingredients is beyond the

scope of these guidelines.

In difficult cases of otitis externa in which the

patient has failed numerous treatment protocols

and/or there is no resolution after 3–6mooftreat-

ment, collaborative care with a board-certified der-

matologist is recommended as this h as been shown

to significantly improve resolution of chronic otitis

with infection.

54

Treatment recommendations for secondary infections in AOE

are beyond the scope of these guidelines.

Short-term and Long-term Management of AOE

The short-term goal of therapy is to reduce inflammation and treat

secondary microbial infection (where present). Oral corticosteroids

in a short, tapering course at anti-inflammatory doses or oclacitinib

may be used for control of inflammation and pruritus. Corticoster-

oids applied topically are also effective.

The long-term goal of therapy focuses on control of inflamma-

tion and maintenance of ear health. Managing the underlying allergy

is key to minimizing AOE. When crafting an allergy management

plan in patients with AOE, one must be mindful that medications

used to manage atopic dermatitis have varying efficacy against AOE

and individual patient response must be assessed.

Routine, topical maintenance therapies are often very helpful in

reducing the recurrence of AOE. Routine ear cleaning based on an

individual patient’s needs is useful to maintain a healthy microenvi-

ronment and remove debris and ceruminous material from the ear

canals. Cleansing agents that promote epidermal barrier function are

useful to reduce microbial adherence to the epithelium and should

be considered in individuals prone to secondary infection. Topical

glucocorticoids (e.g., hydrocortisone and dexamethasone) aid the

management of inflammation in the ear canal and may help prevent

allergic flares and secondary infections as well.

Referral is indicated if the patient has AOE that is

complicated with secondary i nfection that is not

responding to empiric treatment, if it involves a resis-

tant organism, and/or if the patient has otitis media.

54

Demonstration of ear cleaning technique and topi-