Promoting Health and

Preventing Disease and Injury

Through Workplace Tobacco Policies

CURRENT INTELLIGENCE BULLETIN 67

DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health

On the cover: e cover design includes a wispy background image intended to evoke the well-known health

hazard of smoke associated with the use of combustible tobacco products, and the much less studied misty

emissions associated with the use of electronic devices to “vape” liquids containing nicotine and other com-

ponents. e full range of hazards associated with tobacco use extends well beyond such air contaminants, so

the cover design also incorporates a text box to highlight the optimal “Tobacco-Free” (i.e., not just “Smoke-

Free”) status for both workplaces and workers. e text box also evokes the NIOSH Total Worker Health

TM

strategy. is strategy maintains a strong focus on protection of workers against occupational hazards,

including exposure to secondhand tobacco smoke on the job, while additionally encompassing workplace

health promotion to target lifestyle risk factors, including tobacco use by workers. Photo by ©inkstock.

Current Intelligence Bulletin 67

Promoting Health and

Preventing Disease and Injury

Through Workplace Tobacco Policies

DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health

Robert M. Castellan, MD, MPH; L. Casey Chosewood, MD; Douglas Trout, MD;

Gregory R. Wagner, MD; Claire C. Caruso, PhD, RN, FAAN; Jacek Mazurek,

MD, MS, PhD; Susan H. McCrone, PhD, RN; David N. Weissman, MD

ii

NIOSH CIB 67

•

Workplace Tobacco Policies

This document is in the public domain and may be freely copied

or reprinted.

Disclaimer

Mention of any company or product does not constitute endorsement by the National In-

stitute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH). In addition, citations to websites ex-

ternal to NIOSH do not constitute NIOSH endorsement of the sponsoring organizations

or their programs or products. Furthermore, NIOSH is not responsible for the content of

these websites. All Web addresses referenced in this document were accessible as of the

publication date.

Ordering Information

To receive documents or other information about occupational safety and health topics,

contact NIOSH at

Telephone: 1–800–CDC–INFO (1–800–232–4636)

TTY: 1–888–232–6348

CDC INFO: www.cdc.gov/info

or visit the NIOSH website at www.cdc.gov/niosh.

For a monthly update on news at NIOSH, subscribe to NIOSH eNews by visiting www.cdc.

gov/niosh/eNews.

Suggested Citation

NIOSH [2015]. Current intelligence bulletin 67: promoting health and preventing disease

and injury through workplace tobacco policies. By Castellan RM, Chosewood LC, Trout D,

Wagner GR, Caruso CC, Mazurek J, McCrone SH, Weissman DN. Morgantown, WV: U.S.

Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention,

National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, DHHS (NIOSH) Publication No.

2015-113, http://www.cdc.gov/niosh/docs/2015-113/.

DHHS (NIOSH) Publication No. 2015–113

April 2015

Safer • Healthier • People

TM

iii

NIOSH CIB 67

•

Workplace Tobacco Policies

Foreword

Current Intelligence Bulletins (CIBs) are issued by the National Institute for Occupational

Safety and Health (NIOSH) to disseminate new scientic information about occupational

hazards. A CIB may draw attention to a formerly unrecognized hazard, report new data on

a known hazard, or disseminate information about hazard control.

Public health eorts to prevent disease caused by tobacco use have been underway for the

past half century, but more remains to be done to achieve a society free of tobacco-

related death and disease. e Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), of which

NIOSH is a part, has recently proclaimed a “Winnable Battle” to reduce tobacco use. NIOSH

marks a half century since the rst Surgeon General’s Report on the health consequences of

smoking by disseminating this CIB 67, Promoting Health and Preventing Disease and Injury

through Workplace Tobacco Policies.

Workers who use tobacco products, or who are employed in workplaces where smoking

is allowed, are exposed to carcinogenic and other toxic components of tobacco and to-

bacco smoke. Cigarette smoking is becoming less frequent, and smoke-free and tobacco-

free workplace policies are reducing exposure to secondhand smoke (SHS) and motivating

smokers to quit—but millions of workers still smoke, and smoking is still permitted in

many workplaces. Other forms of tobacco also represent a health hazard to workers who

use them. In addition to direct adverse eects of tobacco on the health of workers who use

tobacco products or are exposed to SHS, tobacco products used in the workplace—and

away from work—can worsen the hazardous eects of other workplace exposures.

is CIB addresses the following aspects of tobacco use:

• Tobacco use among workers.

• Exposure to secondhand smoke in workplaces.

• Occupational health and safety concerns relating to tobacco use by workers.

• Existing occupational safety and health regulations and recommendations prohibit-

ing or limiting tobacco use in the workplace.

• Hazards of worker exposure to SHS in the workplace.

• Interventions aimed at eliminating or reducing these hazards.

is CIB concludes with NIOSH recommendations on tobacco use in places of work and

tobacco use by workers.

NIOSH urges all employers to embrace a goal that all their workplaces will ultimately be made

and maintained tobacco-free. Initially, at a minimum, employers should take these actions:

• Establish their workplaces as smoke-free (encompassing all indoor areas without ex-

ceptions, areas immediately outside building entrances and air intakes, and all work

vehicles).

iv

NIOSH CIB 67

•

Workplace Tobacco Policies

• Assure compliance with OSHA and MSHA regulations that prohibit or otherwise re-

strict smoking, smoking materials, and/or use of other tobacco products in desig-

nated hazardous work areas.

• Provide cessation support for their employees who continue to use tobacco products.

• Doing all this will help fulll employers’ fundamental obligation to provide safe work-

places, and these actions can improve the health and well-being of their workers.

John Howard, M.D.

Director, National Institute for Occupational

Safety and Health

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

v

NIOSH CIB 67

•

Workplace Tobacco Policies

Executive Summary

Introduction

Various NIOSH criteria documents on individual hazardous industrial agents, from asbes-

tos [NIOSH 1972] through hexavalent chromium [NIOSH 2013a], have included specic

recommendations relating to tobacco use, along with other recommendations to eliminate

or reduce occupational safety and health risks. In addition, NIOSH has published two Cur-

rent Intelligence Bulletins focused entirely on the hazards of tobacco use. CIB 31, Adverse

Health Eects of Smoking and the Occupational Environment, outlined how tobacco use—

most commonly smoking—can increase risk, sometimes profoundly, of occupational dis-

ease and injury [NIOSH 1979]. In that CIB, NIOSH recommended that smoking be cur-

tailed in workplaces where those other hazards are present and that worker exposure to

those other occupational hazards be controlled. CIB 54, Environmental Tobacco Smoke in

the Workplace: Lung Cancer and Other Health Eects, presented a determination by NIOSH

that secondhand smoke (SHS) causes cancer and cardiovascular disease [NIOSH 1991]. In

that CIB, NIOSH recommended that workplace exposures to SHS be reduced to the lowest

feasible concentration, emphasizing that eliminating tobacco smoking from the workplace

is the best way to achieve that. is current CIB 67, Promoting Health and Preventing Disease

and Injury rough Workplace Tobacco Policies, augments those two earlier NIOSH CIBs.

Consistent with the philosophy embodied in the NIOSH Total Worker Health™ Program

[NIOSH 2013b], this CIB is aimed not just at preventing occupational injury and illness

related to tobacco use, but also at improving the general health and well-being of workers.

Smoking and Other Tobacco Use by Workers—

Exposure to Secondhand Smoke at Work

Millions of workers use tobacco products. Since publication of the rst Surgeon General’s

Report on the health consequences of smoking, cigarette smoking prevalence in the United

States has declined by more than 50% among all U.S. adults—from about 42% in 1965 to

about 18% in 2013 [DHHS 2014; CDC 2014d]. Overall, smoking among workers has simi-

larly declined, but smoking rates among blue-collar workers have been shown to be consis-

tently higher than among white-collar workers. Among blue-collar workers, those exposed

to higher levels of workplace dust and chemical hazards are more likely to be smokers [Chin

et al. 2012]. Also, on average, blue-collar smokers smoke more heavily than white-collar

smokers [Fujishiro et al. 2012].

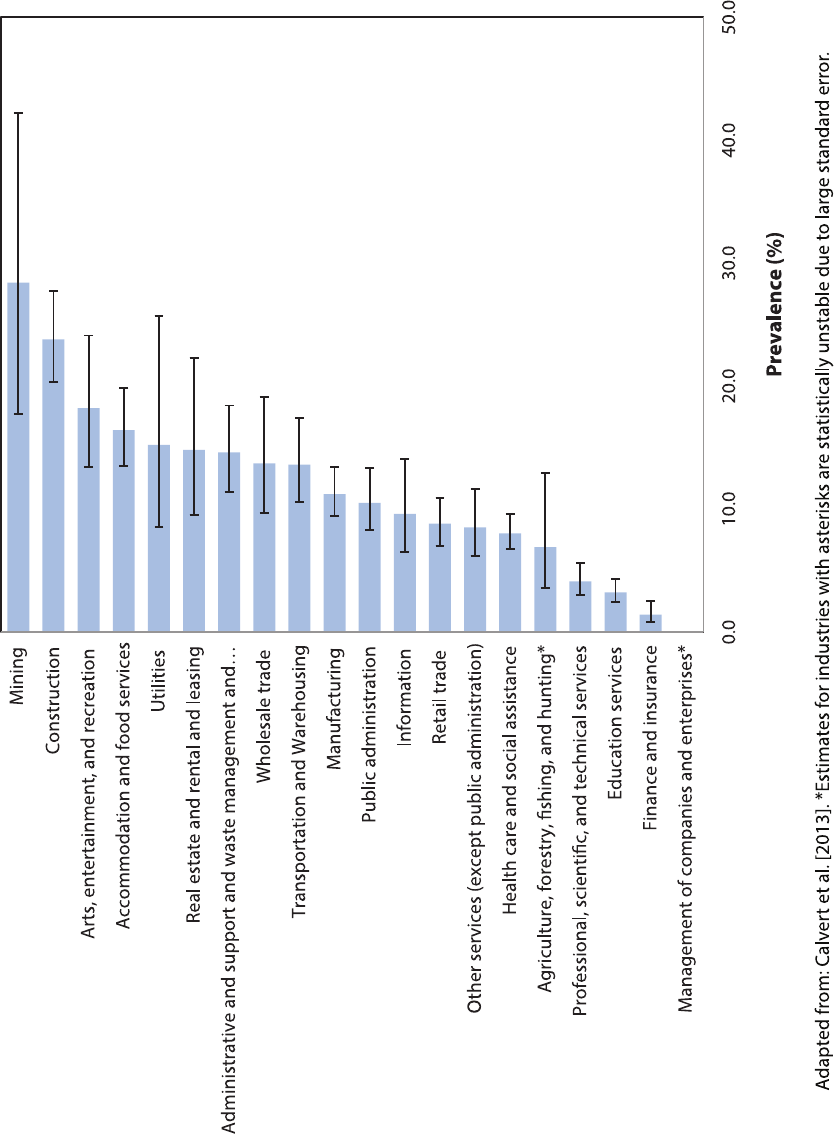

From 2004–2011, cigarette smoking prevalence varied widely by industry, ranging from

about 10% in education services to more than 30% in construction, mining, and accom-

modation and food services. Smoking prevalence varies even more by occupation, ranging

from 2% among religious workers to 50% among construction trades helpers [NIOSH

2014]. A recent survey of U.S. adults found that by 2013, approximately 1 in 3 current

vi

NIOSH CIB 67

•

Workplace Tobacco Policies

smokers reported ever having used e-cigarettes, a type of electronic nicotine delivery sys-

tem (ENDS) [King et al. 2015]. However, the prevalence of ENDS use by industry and occu-

pation has not been studied. Overall, about 3% of all workers use smokeless tobacco in the

form of chewing tobacco and snu, but smokeless tobacco use exceeds 10% among workers

in construction and extraction jobs and stands at nearly 20% among workers in the mining

industry [NIOSH 2014]. e use of smokeless tobacco by persons who also smoke tobacco

products—one form of what is known as “dual use”—is a way some workers maintain their

nicotine habit in settings where smoking is prohibited (e.g., in an oce where indoor smok-

ing is prohibited or in coal mines where smoking can cause explosions). More than 4% of

U.S. workers who smoke cigarettes also use smokeless tobacco [CDC 2014b; NIOSH 2014].

e implementation of smoke-free policies has eliminated or substantially decreased ex-

posure to SHS in many U.S. workplaces. But millions of nonsmoking workers not covered

by these policies are still exposed to SHS in their workplace. A 2009–2010 survey found

that 20.4% of nonsmoking U.S. workers experienced exposure to SHS at work on at least 1 day

during the preceding week [King et al. 2014]. Another survey conducted at about the

same time estimated that 10.0% of nonsmoking adult U.S. workers experienced exposure

to SHS at work on at least 2 days per week during the past year [Calvert et al. 2013]. Such

exposure varied by industry (ranging from 4% for nance and insurance to nearly 28%

for mining) and by occupation (ranging from 2% for education, training, and library oc-

cupations to nearly 29% for construction and extraction occupations). Inclusion of ENDS

in smoke-free policies has increased over time. In the United States, the number of states

and localities that explicitly prohibited use of e-cigarettes in public places where tobacco

smoking was already prohibited totaled 3 states and more than 200 localities before the

end of 2014 [CDC 2014c].

Health and Safety Consequences of Tobacco Use

Since the rst Surgeon General’s report on smoking and health, many reports from the Sur-

geon General and other health authorities have documented serious health consequences

of smoking tobacco, exposure to secondhand smoke (SHS), and use of smokeless tobacco.

Smoking is a known cause of the top fıve health conditions impacting the U.S. popula-

tion—heart disease, cancer, cerebrovascular disease, chronic lower respiratory disease, and

unintentional injuries [DHHS 2004, 2014]. Smoking also causes a variety of other diseases,

as well as adverse reproductive eects [DHHS 2004, 2014]. Smoking is responsible for more

than 480,000 premature deaths each year in the U.S. [DHHS 2014]. e risk of most ad-

verse health outcomes caused by smoking is related to the duration and intensity of tobacco

smoking, but no level of tobacco smoking is risk free [DHHS 2010b, 2014].

Likewise, there is no risk-free level of exposure to SHS [DHHS 2006, 2014]. SHS exposure

causes more than 41,000 deaths each year among U.S. nonsmokers [DHHS 2014]. Among

exposed adults, there is strong evidence of a causal relationship between exposure to SHS

and a number of adverse health eects, including lung cancer, heart disease (including

heart attacks), stroke, exacerbation of asthma, and reduced birth weight of ospring (due

to SHS exposure of nonsmoking pregnant women) [DHHS 2006, 2014; IARC 2009; IOM

2010; Henneberger et al. 2011]. In addition, there is suggestive evidence that exposure to

SHS causes a range of other health eects among adults, including other cancers (breast

cancer, nasal cancer), asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and pre-

mature delivery of babies born to women exposed to SHS [DHHS 2006, 2014; IARC 2009].

vii

NIOSH CIB 67

•

Workplace Tobacco Policies

Because ENDS are relatively new products that vary widely and have not been well studied,

limited data are available on potential hazardous eects of active and passive exposures to

their emissions [Brown and Cheng 2014; Orr 2014; Bhatnagar et al. 2014]. A recent white

paper from the American Industrial Hygiene Association thoroughly reviewed the ENDS

issue and cautioned that “… the existing research does not appear to warrant the conclusion

that e-cigarettes are “safe” in absolute terms … e-cigarettes should be considered a source of

volatile organic compounds (VOCs) and particulates in the indoor environment that have

not been thoroughly characterized or evaluated for safety” [AIHA 2014].

Smokeless tobacco is known to cause several types of cancer, including oral, esophageal,

and pancreatic cancers [IARC 2012]. Some newer smokeless tobacco products (e.g., snus)

are processed in a way intended to substantially reduce toxicant and carcinogen content,

though variable residual levels remain even in these newer products and represent poten-

tial risk to users [Stepanov et al. 2008]. All smokeless tobacco products contain nicotine, a

highly addictive substance which is plausibly responsible for high risks of adverse repro-

ductive outcomes (e.g., low birth weight, pre-term delivery, and stillbirth) associated with

maternal use of snus [DHHS 2014].

Combining Tobacco Use and Occupational

Hazards Enhances Risk

Many workers and their employers do not fully understand that tobacco use in their work-

places (most commonly smoking) can increase—sometimes profoundly—the likelihood

and/or the severity of occupational disease and injury caused by other hazards present. is

can occur in various ways. A toxic industrial chemical present in the workplace can also be

present in tobacco products and/or tobacco smoke, so workers who smoke or are exposed

to SHS are more highly exposed and placed at greater risk of the occupational disease as-

sociated with those chemicals.

Heat generated by smoking tobacco in the workplace can transform some workplace

chemicals into more toxic chemicals, placing workers who smoke at greater risk of toxicity

[NIOSH 1979; DHEW 1979b; DHHS 1985]. Tobacco products can readily become con-

taminated by toxic workplace chemicals, through contact of the tobacco products with un-

washed hands or contaminated surfaces and through deposition of airborne contaminants

onto the tobacco products. Subsequent use of the contaminated tobacco products, whether

at or away from the workplace, can facilitate entry of these toxic agents into the user’s body

[NIOSH 1979; DHEW 1979b].

Oen, a health eect can be independently caused by tobacco use and by workplace ex-

posure to a toxic agent. For example, tobacco smoking can reduce a worker’s lung func-

tion, leaving that worker more vulnerable to the eect of any similar impairment of lung

function caused by occupational exposure to dusts, gases, or fumes [NIOSH 1979; DHEW

1979b; DHHS 1985]. For some occupational hazards, the combined impact of tobacco use

and exposure to a toxic occupational agent can be synergistic (i.e., amounting to an eect

profoundly greater than the sum of each independent eect). An example is the combined

synergistic eect of tobacco smoking and asbestos exposure on lung cancer, which results

in a profoundly increased risk of lung cancer among asbestos-exposed workers who smoke

[NIOSH 1979; DHEW 1979b; IARC 2004; Frost et al. 2011; Markowitz et al. 2013]

.

viii

NIOSH CIB 67

•

Workplace Tobacco Policies

e risk of occupational injuries and traumatic fatalities can be greatly enhanced when

tobacco use is combined with an occupational hazard. Obvious examples are explosions

and res when explosive or ammable materials in the workplace are ignited by sources as-

sociated with tobacco smoking [MSHA 2000; OSHA 2013a]. However, any form of tobacco

use may result in traumatic injury if the worker operating a vehicle or industrial machinery

is distracted by tobacco use (e.g., while opening, lighting, extinguishing, or disposing of a

tobacco product) [NIOSH 1979].

Preventive Interventions

Both health and economic considerations can motivate people to quit tobacco use. Work-

ers who smoke can protect their own health by quitting tobacco use and can protect their

coworkers’ health by not smoking in the workplace. Smokers who quit stand to benet -

nancially. Among other savings, they no longer incur direct costs associated with consumer

purchases of tobacco products and related materials, and they generally pay lower life and

health insurance premiums and lower out-of-pocket costs for health care.

Legally determined employer responsibilities set out in federal, state, and local laws and

regulations, as well as health and economic considerations, can motivate employers to

establish workplace policies that prohibit or restrict tobacco use. Even where smoke-free

workplace policies are not explicitly mandated by state or local governments, the general

duty of employers to provide safe work environments for their employees can motivate

employers to prohibit smoking in their workplaces, thereby avoiding liability for exposing

nonsmoking employees to SHS [Zellers et al. 2007]. Also, not only are nonsmoking workers

generally healthier, but they are more productive and less costly for employers. Considering

aggregate cost and productivity impacts, one recent study estimated that the annual cost

to employ a smoker was, on average, nearly $6,000 greater than the cost to employ a non-

smoker [Berman et al. 2013]. It follows that interventions that help smoking workers quit

can benet the bottom line of a business.

Several studies have shown that smoke-free workplace policies decrease exposure of non-

smoking employees to SHS at work, increase smoking cessation, and decrease smoking

rates among employees [Fichtenberg and Glantz 2002; Bauer et al. 2005; DHHS 2006; IARC

2009; Hopkins et al. 2010]. Less restrictive workplace smoking policies are associated with

higher levels of sustained tobacco use among workers [IARC 2009]. In workplaces without

a workplace rule that limits smoking, workers are signicantly more likely to be smokers

[Ham et al. 2011]. Policies that make indoor workplaces smoke-free result in improved

worker health [IARC 2009; Callinan et al. 2010]. For example, smoke-free policies in the

hospitality industry have been shown to improve health among bar workers, who are oen

heavily exposed to SHS in the absence of such policies [Eisner et al. 1998; DHHS 2006;

IARC 2009]. Smoke-free policies also reduce hospitalizations for heart attacks in the gen-

eral population [IARC 2009; IOM 2010; Tan and Glantz 2012; DHHS 2014] and several

recent studies suggest that these policies may also reduce hospitalizations and emergency

department visits for asthma in the general population [Hahn 2010; Mackay et al. 2010; Tan

and Glantz 2012; Herman and Walsh 2011]. e CDC-administered Task Force on Com-

munity Preventive Services recommends smoke-free workplace policies, not only to reduce

exposure to SHS, but also to increase tobacco cessation, reduce tobacco use prevalence, and

reduce tobacco-related morbidity and mortality [Hopkins et al. 2010; Task Force on Com-

munity Preventive Services 2010; GCPS 2012a].

ix

NIOSH CIB 67

•

Workplace Tobacco Policies

Some employers have taken action to extend restrictions on tobacco use by their employ-

ees beyond the workplace, for example by prohibiting smoking by workers during their

workday breaks, when away from the workplace, including during lunchtime. Several large

employers have gone further by barring the hiring of smokers. Such wide-ranging poli-

cies generate substantial controversy and are illegal in some jurisdictions [Asch et al. 2013;

Schmidt et al. 2013].

Workplace Tobacco Use Cessation Programs

Employees who smoke and want to quit can benet from employer-provided resources

and assistance. Various levels and types of cessation support can be provided to workers,

though more intensive intervention has a greater eect [Clinical Practice Guideline 2008].

Occupational health providers and worksite health promotion sta can increase quit rates

simply by asking about a worker’s tobacco use and oering brief counseling [O’Hara et al.

1993; Clinical Practice Guideline 2008]. Workers who smoke can be referred to publicly

funded state quitlines, which have been shown to increase tobacco cessation success [GCPS

2012b; Clinical Practice Guideline 2008]. Widespread availability, ease of accessibility, af-

fordability, and potential reach to populations with higher levels of tobacco use make quit-

lines an important component of any cessation eort [Clinical Practice Guideline 2008].

However, many employers do not make their employees aware of them [Hughes et al. 2011].

Mobile phone texting interventions and web-based interventions are also promising ap-

proaches to assist with tobacco cessation [Graham et al. 2007; Clinical Practice Guideline

2008; Whittaker et al. 2011; Civljak et al. 2013]. e most comprehensive workplace cessa-

tion programs incorporate tobacco cessation support into programs that address the overall

safety, health, and well-being of workers. A growing evidence base supports the enhanced

eectiveness of workplace health promotion programs when they are combined with oc-

cupational health protection programs [Sorensen et al. 2003; Barbeau et al. 2006; Hymel et

al. 2011; NIOSH 2013b].

Health Insurance and Smoking—Using Incentives

and Disincentives to Modify Tobacco Use Behavior

Many workers are covered by employer-provided health insurance, which is increasingly

being designed to encourage and help employees to adopt positive personal health-related

behaviors, including smoking cessation for smokers. Health insurance coverage of evi-

dence-based smoking cessation treatments is associated with increases in the number of

smokers who attempt to quit, use proven treatments in these attempts, and succeed in quit-

ting [Clinical Practice Guideline 2008]. Ideally, such coverage should provide access to all

evidence-based cessation treatments, including individual, group, and telephone counsel-

ing, and all seven FDA-approved cessation medications, while eliminating or minimizing

barriers such as cost-sharing and prior authorization [Clinical Practice Guideline 2008;

CDC 2014b].

e Aordable Care Act (ACA), Public Law 111-148, includes provisions pertinent to to-

bacco use and cessation [McAfee et al. 2015]. Some of these provisions are intended to

help smokers quit by increasing their access to proven cessation treatments. Other ACA

provisions are intended to encourage tobacco cessation by permitting small-group plans

to charge tobacco users premiums that are up to 50% higher than those charged to non-

tobacco users, subject certain limitations [78 Fed. Reg. 33158].

x

NIOSH CIB 67

•

Workplace Tobacco Policies

e appropriate intent of incentives is to help employees who use tobacco quit, thus im-

proving health and reducing health-care costs overall. e evidence for the eectiveness

of imposing insurance premium surcharges on tobacco users is limited, and care is need-

ed to ensure that incentive programs are designed to work as intended and to minimize

the potential use of incentives in an unduly coercive or discriminatory manner [Madison

et al. 2011, 2013]. e Task Force on Community Preventive Services has recommended

worksite-based incentives and competitions that are combined with other evidence-based

interventions (e.g., education, group support, telephonic counseling, self-help materials,

smoke-free workplace policies) as part of a comprehensive cessation program [GCPS 2005].

Conclusions

• Cigarette smoking by workers and SHS exposure in the workplace have both declined

substantially over recent decades, but about 20% of all U.S. workers still smoke and

about 20% of nonsmoking workers are still exposed to SHS at work.

• Smoking prevalence among workers varies widely by industry and occupation, ap-

proaching or exceeding 30% in construction, mining, and accommodation and food

services workers.

• Prevalence of ENDS use by occupation and industry has not been studied, but ENDS

has grown greatly, with about 1 in 3 current U.S. adult smokers reporting ever having

used e-cigarettes by 2013.

• Smokeless tobacco is used by about 3% of U.S. workers overall, but smokeless tobacco

is used by more than 10% workers in construction and extraction jobs and by nearly

20% of workers in the mining industry, which can be expected to result in disparities

in tobacco-related morbidity and mortality.

• Tobacco use causes debilitating and fatal diseases, including cancer, respiratory dis-

eases, and cardiovascular diseases. ese diseases aict mainly users, but they also

occur in those exposed to SHS. Smoking is substantially more hazardous, but use of

smokeless tobacco also causes adverse health eects. More than 16 million U.S. adults

live with a disease caused by smoking, and each year nearly a half million die prema-

turely from smoking or exposure to SHS.

• Tobacco use is associated with increased risk of injury and property loss due to re,

explosion, and vehicular collisions.

• Tobacco use by workers can increase, sometimes profoundly, the likelihood and the

severity of occupational disease and injury caused by other workplace hazards (e.g.,

lead, asbestos, and ammable materials).

• Restrictions on smoking and tobacco use in specic work areas where particular

high-risk occupational hazards are present (e.g., explosives, highly ammable materi-

als, or highly toxic materials that could be ingested via tobacco use) have long been

used to protect workers.

• A risk-free level of exposure to SHS has not been established, and ventilation is insuf-

cient to eliminate indoor exposure to SHS.

• Potential adverse health eects associated with using ENDS or secondhand exposure

to particulate aerosols and gases emitted from ENDS remains to be fully characterized.

xi

NIOSH CIB 67

•

Workplace Tobacco Policies

• Policies that prohibit tobacco smoking throughout the workplace (i.e., smoke-free

workplace policies) are now widely implemented, but they have not yet been univer-

sally adopted across the United States. ese policies improve workplace air qual-

ity, reduce SHS exposure and related health eects among nonsmoking employees,

increase the likelihood that workers who smoke will quit, decrease the amount of

smoking during the working day by employees who continue to smoke, and have an

overall impact of improving the health of workers (i.e., among both nonsmokers who

are no longer exposed to SHS on the job and smokers who quit).

• Workplace-based eorts to help workers quit tobacco use can be easily integrated into

existing occupational health and wellness programs. Even minimal counseling and/or

simple referral to state quitlines, mobile phone texting interventions, and web-based

intervention can be eective, and more comprehensive programs are even more ef-

fective.

• Integrating both occupational safety and health protection components into work-

place health promotion programs (e.g., smoking cessation) can increase participation

in tobacco cessation programs and successful cessation among blue-collar workers.

• Smokers, on average, are substantially more costly to employ than nonsmokers.

• Some employers have policies that prohibit employees from using tobacco when away

from work or that bar the hiring of smokers or tobacco users. However, the ethics

of these policies remain under debate, and they may be legally prohibited in some

jurisdictions.

Recommendations

NIOSH recommends that employers take the following actions related to employ-

ee tobacco use:

• At a minimum, establish and maintain smoke-free workplaces that protect those in

workplaces from involuntary, secondhand exposures to tobacco smoke and airborne

emissions from e-cigarettes and other electronic nicotine delivery systems. Ideally,

smoke-free workplaces should be established in concert with tobacco cessation sup-

port programs. Smoke-free zones should encompass (1) all indoor areas without ex-

ceptions (i.e., no indoor smoking areas of any kind, even if separately enclosed and/

or ventilated), (2) all areas immediately outside building entrances and air intakes,

and (3) all work vehicles. Additionally, ashtrays should be removed from these areas.

• Optimally, establish and maintain entirely tobacco-free workplaces, allowing no use

of any tobacco products across the entire workplace campus (see model policy in

Box 6-1).

• Comply with current OSHA and MSHA regulations that prohibit or limit smoking,

smoking materials, and/or use of other tobacco products in work areas characterized

by the presence of explosive or highly ammable materials or potential exposure to

toxic materials (see Table A-3 in the Appendix). To the extent feasible, follow all simi-

lar NIOSH recommendations (see Table A-2 in the Appendix).

• Provide information on tobacco-related health risks and on benets of quitting to all

employees and other workers at the worksite (e.g., contractors and volunteers).

ȣ Inform all workers about health risks of tobacco use.

ȣ Inform all workers about health risks of exposure to SHS.

ȣ Train workers who are exposed or potentially exposed to occupational hazards at

work about increased health and/or injury risks of combining tobacco use with

exposure to workplace hazards, about what the employer is doing to limit the

risks, and about what the worker can do to limit his/her risks.

• Provide information on employer-provided and publicly available tobacco cessation

services to all employees and other workers at the worksite (e.g., contractors and vol-

unteers).

ȣ At a minimum, include information on available quitlines, mobile phone texting

interventions, and web-based cessation programs, self-help materials, and

employer-provided cessation programs and tobacco-related health insurance

benets available to the worker.

ȣ Ask about personal tobacco use as part of all occupational health and

wellness program interactions with individual workers and promptly provide

encouragement to quit and guidance on tobacco cessation to each worker

identied as a tobacco user and to any other worker who requests tobacco

cessation guidance.

• Oer and promote comprehensive tobacco cessation support to all tobacco-using

workers and, where feasible, to their dependents.

ȣ Provide employer-sponsored cessation programs at no cost or subsidize cessation

programs for lower-wage workers to enhance the likelihood of their participation.

If health insurance is provided for employees, the health plan should provide

comprehensive cessation coverage, including all evidence-based cessation

treatments, unimpeded by co-pays and other nancial or administrative barriers.

ȣ Include occupational health protection content specic to the individual

workplace in employer-sponsored tobacco cessation programs oered to workers

with jobs involving potential exposure to other occupational hazards.

• Become familiar with available guidance (e.g., CDC’s “Implementing a Tobacco-Free

Campus Initiative in Your Workplace”) (see Box 6-2) and federal guidance on tobacco

cessation insurance coverage under the ACA (e.g., http://www.dol.gov/ebsa/faqs/faq-

aca19.html) before developing, implementing, or modifying tobacco-related policies,

interventions, or controls.

• Develop, implement, and modify tobacco-related policies, interventions, and controls

in a stepwise and participatory manner. Get input from employees, labor represen-

tatives, line management, occupational safety/health and wellness sta, and human

resources professionals. ose providing input should include current and former to-

bacco users, as well as those who have never used tobacco. Seek voluntary input from

employees with health conditions, such as heart disease and asthma, exacerbated by

exposure to SHS.

• Make sure that any dierential employment benets policies that are based on to-

bacco use or participation in tobacco cessation programs are designed with a primary

intent to improve worker health and comply with all applicable federal, state, and lo-

cal laws and regulations. Even when permissible by law, these dierential employment

benet policies—as well as dierential hiring policies based on tobacco use—should

be implemented only after seriously considering ethical concerns and possible

xiii

NIOSH CIB 67

•

Workplace Tobacco Policies

unintended consequences. ese consequences can include the potential for adverse

impacts on individual employees (e.g., coercion, discrimination, and breach of priva-

cy) and the workforce as a whole. Furthermore, the impact of any dierential policies

that are introduced should be monitored to determine whether they improve health

and/or have unintended consequences.

NIOSH recommends that workers who smoke cigarettes or use other tobacco products take

the following actions:

• Comply with all workplace tobacco policies.

• Ask about available employer-provided tobacco cessation programs and cessation-

related health insurance benets.

• Quit using tobacco products. Know that quitting tobacco use is benecial at any age,

but the earlier one quits, the greater the benets. Many people nd various types

of assistance to be very helpful in quitting, and evidence-based cessation treatments

have been found to increase smokers’ chances of quitting successfully. Workers can

get help from

ȣ tobacco cessation programs, including web-based programs (e.g., http://smokefree.

gov and http://www.cdc.gov/tips) and mobile phone texting services (e.g., the

SmokefreeTXT program, http://smokefree.gov/smokefreetxt);

ȣ state quitlines (phone: 1-800-QUIT-NOW [1-800-784-8669], or 1-855-DEJELO-YA

[1-855-335-3569 for Spanish-speaking callers]); and/or

ȣ health-care providers.

In addition, individual workers who want to quit tobacco may nd several of the websites

listed in Box 6-2 helpful.

NIOSH recommends that all workers, including workers who use tobacco and nonsmokers

exposed to SHS at their workplace:

• know the occupational safety and health risks associated with their work, includ-

ing those that can be made worse by personal tobacco use, and how to limit those

risks; and

• consider sharing a copy of this CIB with their employer.

is page intentionally le blank.

Contents

Foreword ................................................................. iii

Executive Summary ........................................................ v

Introduction .......................................................... v

Smoking and Other Tobacco Use by Workers—Exposure to

Secondhand Smoke at Work

........................................... v

Health and Safety Consequences of Tobacco Use ........................... vi

Combining Tobacco Use and Occupational Hazards Enhances Risk .......... vii

Preventive Interventions ................................................ viii

Workplace Tobacco Use Cessation Programs .............................. ix

Health Insurance and Smoking—Using Incentives

and Disincentives to Modify Tobacco Use Behavior

...................... ix

Conclusions .......................................................... x

Recommendations ..................................................... xi

Abbreviations ............................................................. xvii

Acknowledgments ......................................................... xviii

1 Background ............................................................. 1

2 Tobacco Use by Workers and Secondhand Smoke Exposures at Work ............ 3

Use of Conventional Tobacco Products by Workers ......................... 3

Tobacco Smoking ................................................... 3

Smokeless Tobacco ................................................. 3

Dual Use .......................................................... 4

Secondhand Smoke Exposures at Work ................................... 4

Electronic Nicotine Delivery Systems ..................................... 5

3 Health and Safety Consequences of Tobacco Use .............................. 7

Health Problems Caused by Use of Tobacco Products ....................... 7

Tobacco Smoking ................................................... 7

Secondhand Smoke ................................................. 10

Smokeless Tobacco ................................................. 10

Electronic Nicotine Delivery Systems .................................. 12

Traumatic Injuries and Fatalities Caused by Tobacco Use ................ 13

Tobacco Use and Increased Risk of Work-related Disease and Injury ....... 13

4 Preventive Interventions .................................................. 19

Workplace Policies Prohibiting or Restricting Smoking ..................... 21

Employer Prohibitions on Tobacco Use Extending Beyond the Workplace ..... 24

Workplace Tobacco Use Cessation Programs .............................. 25

xvi

NIOSH CIB 67

•

Workplace Tobacco Policies

Health Insurance and Smoking Behavior .................................. 26

Using Incentives and Disincentives to Modify Tobacco Use Behavior ......... 28

5 Conclusions ............................................................. 31

6 Recommendations ....................................................... 33

References ................................................................ 41

Appendix ................................................................. 57

xvii

NIOSH CIB 67

•

Workplace Tobacco Policies

Abbreviations

ACA Aordable Care Act

CDC Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

CIB Current Intelligence Bulletin

COPD chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

ENDS electronic nicotine delivery system

FDA Food and Drug Administration

MSHA Mine Safety and Health Administration

NHIS National Health Interview Survey

NIOSH National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health

OEL occupational exposure limit

OSHA Occupational Safety and Health Administration

SHS secondhand smoke

SIDS sudden infant death syndrome

xviii

NIOSH CIB 67

•

Workplace Tobacco Policies

Acknowledgments

For contributions to the technical content and review of this document, the authors ac-

knowledge the following NIOSH contributors: Toni Alterman, PhD; Richard J. Driscoll,

PhD, MPH; omas R. Hales, MD, MPH; Candice Johnson, PhD; and Anita L. Schill, PhD,

MPH, MA. From the Oce of Smoking and Health, CDC: Stephen Babb, MPH.

John Lechliter and Seleen Collins provided editorial support, and Vanessa Williams con-

tributed to the design and layout of this document.

e following external peer reviewers provided comments on a dra of this CIB:

William S. Beckett, MD, MPH

Associate Professor of Medicine

Harvard Medical School

Richard A. Daynard, JD, PhD

University Distinguished Professor of Law

Northeastern University School of Law

James A. Merchant, MD, DrPH

Professor of Occupational and Environmental Health

University of Iowa College of Public Health

Kristin M. Madison, JD, PhD

Professor of Law and Health Sciences

Northeastern University School of Law

Jonathan M. Samet, MD, MS

Distinguished Professor andFloraL. ornton Chair

Department of Preventive Medicine

University of Southern California Keck School of Medicine

Comments on a dra of this document were also submitted to the NIOSH docket by in-

terested stakeholders and other members of the public. All comments were considered in

preparing this nal version of the document.

is page intentionally le blank.

is page intentionally le blank.

1

NIOSH CIB 67

•

Workplace Tobacco Policies

1 Background

e widespread recognition that tobacco use is the

leading preventable cause of premature death and

a major cause of preventable disease, injury, and

disability in the United States is based on an ex-

traordinarily strong scientic foundation. e rst

Surgeon General’s report on smoking and health,

issued a half century ago, concluded that cigarette

smoke causes lung cancer and chronic bronchitis

[DHEW 1964]. Subsequent reports of the Surgeon

General have determined that both active tobacco

smoking and secondhand smoke (SHS) exposure

are important causes of cancer, heart disease, and

respiratory disease, and that smokeless tobacco use

also causes serious disease, including oral, esoph-

ageal, and pancreatic cancer [e.g., DHHS 1982;

1983; 1984; 1986a,b; 2004; 2006; 2014]. One Sur-

geon General’s report focused entirely on smoking-

enhanced risks of cancer and chronic lung disease

for workers exposed to hazardous industrial agents

in the workplace [DHHS 1985]. Several reports of

the Surgeon General have addressed benets of

eective smoking cessation programs and other

means of reducing tobacco use [DHHS 1990, 2000,

2012, 2014].

A Surgeon General’s report also established the

ongoing Healthy People strategy, aimed broadly at

improving the nation’s health [DHEW 1979a]. Cur-

rently, Healthy People 2020 includes a major goal of

reducing “illness, disability, and death related to to-

bacco use and secondhand smoke exposure” along

with several specic objectives that target eliminat-

ing tobacco smoking in workplaces [DHHS 2013].

e Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has

declared reducing tobacco use a “Winnable Battle,”

noting that tobacco use is one of several “public

health priorities with large-scale impact on health

and with known, eective strategies to address

them” [CDC 2013a]. e U.S. Department of Health

and Human Services has published a strategic plan

for tobacco control that envisions “a society free of

tobacco-related death and disease” [DHHS 2010a].

Over time, National Institute for Occupation-

al Safety and Health (NIOSH) publications have

evolved in how they have acknowledged and made

recommendations about hazards associated with

tobacco use by workers. e rst criteria document

published by NIOSH—on asbestos—only briey

mentioned smoking. Smoking was addressed in

the context of a discussion of research ndings that

concluded that smoking alone could not explain

the extremely high risk of lung cancer observed in

asbestos-exposed workers. Smoking was also men-

tioned in a suggestion that the medical monitor-

ing recommended by NIOSH for asbestos-exposed

workers would oer opportunity for various forms

of individualized medical management, including

smoking cessation [NIOSH 1972] (see Appendix

Table A-2). Nearly a decade later, aer substantial-

ly more research on asbestos had been published,

NIOSH disseminated a document arming syn-

ergistic (i.e., more than additive) eects on lung

cancer risk of combined exposure to asbestos and

smoking [NIOSH 1980].

In the late 1970s, NIOSH scientists authored a

chapter on “e Interaction between Smoking

and Occupational Exposure” in the 1979 Surgeon

General’s Report on Smoking and Health [DHEW

1979b]. at work led directly to the rst NIOSH

publication focused solely on tobacco smoke, a

Current Intelligence Bulletin (CIB) that outlined

several ways in which tobacco use can increase,

sometimes profoundly, the risk of occupational dis-

ease and injury [NIOSH 1979]. In that CIB, NIOSH

recommended that smoking be curtailed in work-

places where those other hazards are present and

that worker exposure to those other occupational

hazards be controlled (see Appendix Table A-1).

2 3

NIOSH CIB 67

•

Workplace Tobacco Policies NIOSH CIB 67

•

Workplace Tobacco Policies

Later, when scientic evidence became clear that

the health risk from inhaling tobacco smoke is

not limited to smokers but also aects bystanders,

NIOSH published another CIB focused solely on

tobacco smoke—this one on SHS in the workplace

[NIOSH 1991]. In that CIB, NIOSH presented its

determination that SHS (referred to in that docu-

ment as “environmental tobacco smoke”) causes

cancer and cardiovascular disease. In recommend-

ing that workplace exposures to SHS be reduced to

the lowest feasible concentration using all available

preventive measures, NIOSH emphasized that the

best approach is to eliminate tobacco smoking in

the workplace, and it endorsed employer-provided

smoking cessation programs for employees who

smoke [NIOSH 1991] (see Appendix Table A-1).

In retrospect, the CIB on SHS in the workplace

marked a watershed in the Institute’s approach to

occupational safety and health. Over time, NIOSH

recommendations concerning specic industrial

hazards—which earlier might have been relatively

silent about what were then narrowly understood

to be strictly personal health-related behaviors like

smoking—have come to embrace a more compre-

hensive preventive approach. is evolution has

been motivated by a better understanding of how

tobacco use adversely impacts occupational dis-

eases and injuries and—perhaps just as important-

ly—by a changing societal view of the health and

economic consequences of tobacco use. By way of

example, criteria documents produced in the past

decade on two lung hazards—refractory ceramic

bers [NIOSH 2006] and hexavalent chromium

[NIOSH 2013a]—have included entire sections on

smoking cessation, something not seen in earlier

criteria documents (see Appendix Table A-2). In a

2004 medical journal paper, the Director of NIOSH

concluded that “Smoking is an occupational haz-

ard, both for the worker who smokes and for the

nonsmoker who is exposed to [SHS] in his or her

workplace.” He also recommended that “Smoking

as an occupational hazard should be completely

eliminated for the sake of the health and safety of

American workforce” [Howard 2004]. A 2010 post

on the NIOSH Blog site pointed out that “Tobacco-

free workplaces, on-site tobacco cessation services,

and comprehensive, employer-sponsored health-

care benets that provide multiple quit attempts,

have all been shown to increase tobacco treatment

success” [Howard et al. 2010].

us, instead of staying focused nearly exclusively

on protecting workers from specic occupational

hazards, NIOSH has progressively adopted a “strat-

egy integrating occupational safety and health pro-

tection with health promotion to prevent worker

injury and illness and to advance health and well-

being” [NIOSH 2013b]. is integrated approach,

embodied by NIOSH in its Total Worker Health™

Program [Schill and Chosewood 2013], has mo-

tivated NIOSH to produce this CIB, Promoting

Health and Preventing Disease and Injury through

Workplace Tobacco Policies.

2 3

NIOSH CIB 67

•

Workplace Tobacco Policies NIOSH CIB 67

•

Workplace Tobacco Policies

2 Tobacco Use by Workers and Secondhand

Smoke Exposures at Work

Use of Conventional Tobacco

Products by Workers

Tobacco Smoking

Since publication of the rst Surgeon General’s

report on the health consequences of smoking,

cigarette smoking prevalence has decreased sub-

stantially among U.S. adults, from 42.4% in 1965 to

17.8% in 2013 [DHHS 2014; CDC 2014d]. Nation-

ally representative studies on the smoking status of

workers in the United States, most oen based on

one or more iterations of the National Health Inter-

view Survey (NHIS), have demonstrated substan-

tial declines in overall cigarette smoking, which are

similar to the decrease in cigarette smoking among

all U.S. adults [Sterling and Weinkam 1976; Nel-

son et al. 1994; Lee et al. 2004, 2007; Barbeau et al.

2004]. e overall prevalence of current cigarette

smoking among workers during the 2004–2010

period was 19.6%, very closely approximating the

prevalence among all U.S. adults, which annually

ranged from a high of 20.9% to a low of 19.3% dur-

ing the 2004–2010 period [CDC 2011a, 2013b].

During the past several decades, a number of stud-

ies have assessed smoking habits among U.S. work-

ers. Consistently, these studies have shown substan-

tially higher cigarette smoking prevalence among

blue-collar workers compared with white-collar

workers, particularly among males [Sterling and

Weinkam 1976; DHHS 1985; Stellman et al. 1988;

Brackbill et al. 1988; Covey et al. 1992; Nelson et al.

1994; Bang and Kim 2001; Barbeau et al. 2004; Lee

et al. 2004, 2007; CDC 2011a; Calvert et al. 2013].

In addition, these studies provide evidence of high-

er intensity of smoking among blue-collar workers

who smoke than white-collar workers who smoke

[Fujishiro et al. 2012]. Among blue-collar workers,

those with higher levels of exposure to dust and

chemical hazards are more likely to be smokers

[Chin et al. 2012].

NIOSH publishes recent data on cigarette smok-

ing status by industry and occupation groupings

in the Work-Related Lung Disease (WoRLD) Sur-

veillance Report and corresponding online updates

[NIOSH 2008a, 2014]. e most recent tables,

covering the period 2004–2011, show that smok-

ing prevalence varies widely—nearly four-fold—by

industry. Smoking prevalence at or below 10% was

found among major industry sectors in education

services (9.8%) and among minor industry sec-

tors in religious, grantmaking, civic, labor, profes-

sional, and similar organizations (10.0%). Smoking

prevalence exceeding 30% was found among three

major industry sectors: construction (32.1%); ac-

commodation and food services (32.1%); and min-

ing (30.2%). Several minor sectors in other major

industries also exceeded 30%: gasoline stations

(37.6%); shing, trapping, and hunting (34.3%);

forestry and logging (32.9%); warehousing and

storage (32.0%); rental and leasing services (31.3%);

wood product manufacturing (30.7%); and non-

metallic mineral product manufacturing (30.4%).

Additional tables posted on that same NIOSH site

show that cigarette smoking prevalence varies even

more extremely—25-fold—by specic occupation-

al group, from 2.0% for religious workers to 49.5%

for construction trades helpers [NIOSH 2014] (see

Appendix Figures A-1a and A-1b).

Smokeless Tobacco

Smokeless tobacco is not burned when used. Types

of smokeless tobacco include chewing tobacco,

4 5

NIOSH CIB 67

•

Workplace Tobacco Policies NIOSH CIB 67

•

Workplace Tobacco Policies

snu, dip, snus, and dissolvable tobacco products.

As with smoking, NHIS data have been used to es-

timate smokeless tobacco use by workers [Dietz et

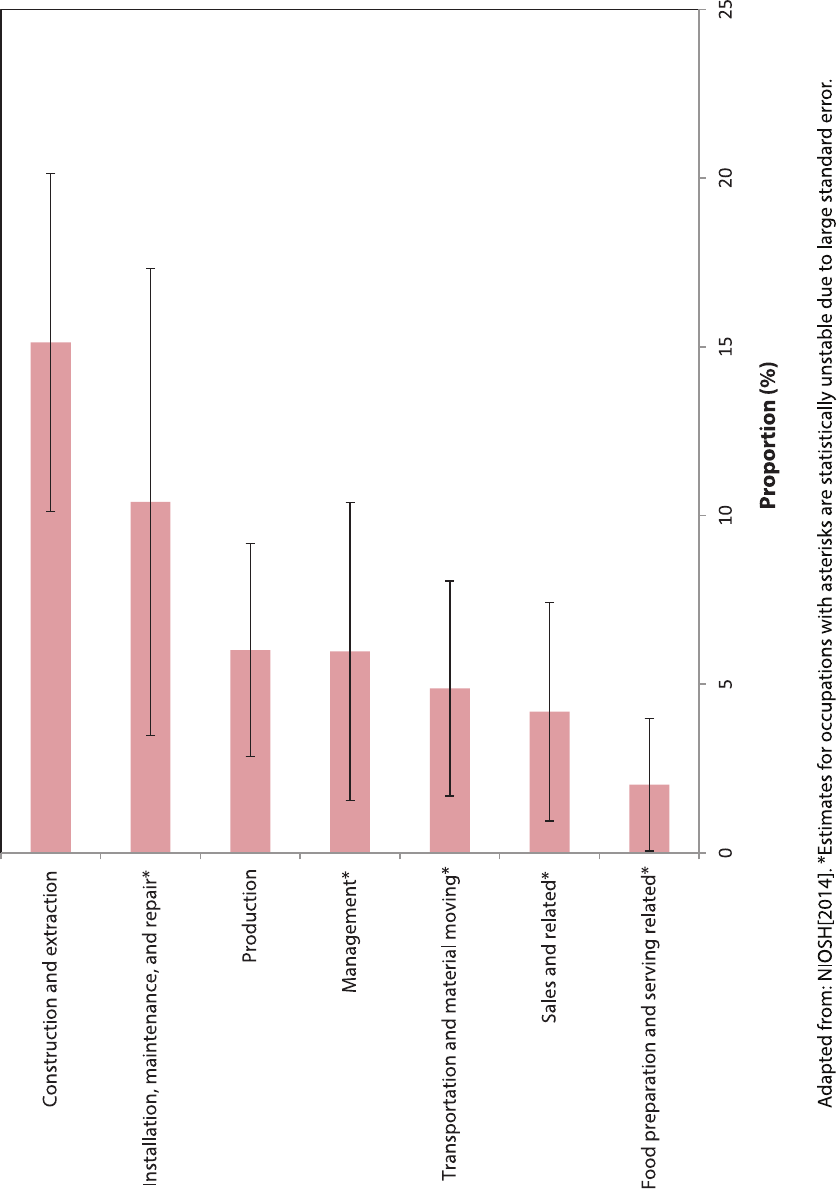

al. 2011; NIOSH 2014]. During 2010, an estimated

3% of currently working adults used smokeless

tobacco in the form of chewing tobacco or snu.

Smokeless tobacco use ranged up to 11% for those

working in construction and extraction jobs and

more than 18% for those working in the mining in-

dustry [CDC 2014a; NIOSH 2014]. (Appendix Fig-

ures A-2a and A-2b display prevalence of smoke-

less tobacco use for major industry and occupation

categories.)

Dual Use

Someone who smokes cigarettes and also uses

smokeless tobacco engages in “dual use.” is is

one way smokers can try to maintain their nico-

tine habit when and where smoking is prohib-

ited. Based on 2010 NHIS data, more than 4% of

U.S. adult workers who smoke cigarettes also use

smokeless tobacco in the form of snu or chewing

tobacco [CDC 2014a; NIOSH 2014]. Dual use has

traditionally been practiced by many workers, in-

cluding coal miners and others, employed in mines

or factories where smoking poses risks for explo-

sion and re [Mejia and Ling 2010]. (Appendix Fig-

ures A-3a and A-3b display prevalence of dual use

among U.S. adult workers who are current smokers

for major industry and occupation categories, re-

spectively.) Use of electronic cigarettes by persons

who also smoke is another form of “dual use” that

is becoming more prevalent as electronic cigarette

use increases (see below, under “Electronic Nico-

tine Delivery Systems”).

Secondhand Smoke

Exposures at Work

SHS is a mixture of the “sidestream smoke” emitted

directly into the air by the burning tobacco product

and the “mainstream smoke” exhaled by smokers

while smoking. Workplace exposures to SHS have

been demonstrated by using air monitoring and

through the use of biological markers, such as co-

tinine, a metabolite of nicotine [Hammond et al.

1995; Hammond 1999; Achutan et al. 2011; Pache-

co et al. 2012]. By the late 1990s, studies that objec-

tively measured markers of SHS found levels that

varied substantially by workplace. Where smoking

was allowed, oces and blue-collar workplaces had

similar concentrations of nicotine in the air; higher

nicotine concentrations were present in restau-

rants, and still higher concentrations (an order of

magnitude higher than in oces) were measured

in bars [Hammond 1999]. More recently, in studies

involving nonsmoking card dealers at three casinos

where smoking was prevalent, objective evidence

of absorption of a cancer-causing component of

SHS (a tobacco-specic nitrosamine) was docu-

mented by showing signicant increases in urine

levels of a metabolite of that component over a

work shi [Achutan et al. 2011]. A comprehensive

review of research on SHS exposures in casinos has

been published elsewhere [Babb et al. 2015].

Smoke-free workplace policies have been increas-

ingly implemented over the past several decades in

the United States and have been shown to be ef-

fective in reducing exposure to SHS [DHHS 2006,

2014]. In a 1986 survey of the civilian U.S. popu-

lation, only 3% of employed respondents reported

working under a smoke-free workplace policy

[CDC 1988]. Subsequent surveys carried out in

the 1990s tracked an increasing proportion of in-

door workers who reported that they worked un-

der a smoke-free workplace policy—46.5% in 1993,

63.7% in 1996, and 69.3% by 1999 [Shopland et al.

2004]. e 1999 survey found wide disparities; al-

though smoke-free workplace policies covered 90%

of school teachers, they covered only 43% of food

preparation and service workers, and only 13% of

bartenders [Shopland et al. 2004].

Although establishment of smoke-free workplace

policies continues to progress in the United States,

these policies are not always 100% eective. A

2009–2010 nationwide survey found that, among

employed nonsmoking adults in the United States

whose workplaces were covered by an indoor

smoke-free policy, 16.4% reported exposure to

4 5

NIOSH CIB 67

•

Workplace Tobacco Policies NIOSH CIB 67

•

Workplace Tobacco Policies

SHS at work 1 or more days during the past 7 days

[King et al. 2014]. Still, this favorably compared

with the much greater 51.3% of those not covered

by smoke-free policies who reported such exposure

to SHS at work [King et al. 2014].

e 2009–2010 nationwide survey also found that

20.4% of nonsmoking employed adults reported

SHS exposure in their indoor workplace on 1 or

more days during the past 7 days [King et al. 2014].

An analysis of recent NHIS data that used a more

restrictive denition of SHS exposure—exposure

to SHS at work on 2 or more days per week dur-

ing the past year—estimated that 10.0% of non-

smoking U.S. workers reported frequent exposure

to SHS at work [Calvert et al. 2013]. Prevalence

of such frequent exposure by major industry sec-

tor ranged from 4.1% for nance and insurance to

28.4% for mining, while prevalence by major oc-

cupation ranged from 2.3% for education, training,

and library occupations to 28.5% for “construction

and extraction” occupations (See Appendix Figures

A-4a and A-4b).

Data from 14 state-based population surveys con-

ducted in 2005 indicated that the majority of all

indoor workers reported a completely smoke-free

workplace policy at their place of employment.

State-specic proportions ranged from 54.8% (Ne-

vada) to 85.8% (West Virginia), with a median of

73.4% [CDC 2006]. Results from later surveys con-

ducted by 13 states in 2008 found proportions of

nonsmoking employed adults who reported SHS

exposure on 2 or more days during the past 7 days

in their indoor workplace ranging from 6.0% (Ten-

nessee) to 15.8% (Mississippi), with a state-specic

median of 8.6% [CDC 2009]. An even more recent

survey involving all states found proportions of

nonsmoking employed adults who reported SHS

exposure on 1 or more days during the past 7 days

in their indoor workplace ranging from 12.4%

(Maine) to 30.8% (Nevada) [King et al. 2014].

Prevalences of SHS exposure at work on 1 or more

days during the past 7 days were signicantly higher

among males (23.8%) than females (16.7%), among

those without a high school diploma (31.9%) than

those with a graduate school degree (11.9%), and

among those with an annual household income less

than $20,000 (24.2%) than those with ≥$100,000

income (14.8%). A recent study separated eects

on workplace SHS exposure associated with educa-

tion and income from eects associated with occu-

pation [Fujishiro et al. 2012]. Even aer statistically

adjusting for the eects of education and income,

blue-collar workers were more likely to report

workplace SHS exposure than managers and pro-

fessionals. at same study also found that blue-

collar workers were also more likely to be smokers

and more likely to be heavy smokers, suggesting

that SHS exposures in the workplace could be in-

tense for many blue-collar workers.

Electronic Nicotine Delivery Systems

First introduced into the U.S. market in 2007 [Re-

gan et al. 2013], electronic nicotine delivery sys-

tems (ENDS), which include electronic cigarettes,

or e-cigarettes, are rapidly increasing in use [King

et al. 2015]. e ENDS marketplace has diversied

in recent years and now includes multiple products,

including electronic hookahs, vape pens, electronic

cigars, and electronic pipes. Typically, an ENDS

product has a cartridge containing a liquid con-

sisting of varying amounts of nicotine, a propylene

glycol and/or glycerin carrier, and avorings. Inha-

lation draws the uid to a heating element, creating

vapor that subsequently condenses into an aerosol

of minute droplets [Ingebrethsen et al. 2012].

Available data suggest that e-cigarette use has in-

creased greatly in the United States during the past

several years. A mail survey of U.S. adults showed

that the percentage who had ever used e-cigarette

more than quadrupled from 0.6% in 2009 to 2.7%

in 2010 [Regan et al. 2013]. A more recent survey

of U.S. adults found that by 2013 approximately 1

in 3 current smokers reported ever having used

e-cigarettes [King et al. 2015]. To date, there have

been no nationally representative surveys of ENDS

use specically among workers or specically in

the workplace.

is page intentionally le blank.

7

NIOSH CIB 67

•

Workplace Tobacco Policies

3 Health and Safety Consequences of

Tobacco Use

Health Problems Caused by

Use of Tobacco Products

Tobacco Smoking

Smoking is a known cause of the top fıve health

conditions impacting the U.S. population—heart

disease, cancer, cerebrovascular disease, chronic

lower respiratory disease, and unintentional inju-

ries [DHHS 2004] (Table 3-1), and each of these is

amenable to preventive intervention [Task Force on

Community Preventive Services 2010]. e risk and

severity of most adverse health outcomes caused by

smoking are directly related to the duration and in-

tensity of tobacco smoking, but no level of tobacco

smoking is risk-free [DHHS 2010b, 2014]. Smok-

ing is responsible for more than 480,000 deaths

each year in the United States [DHHS 2014]. It is

estimated that more than 16 million U.S. adults

live with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

or other disease attributable to tobacco smoking

[DHHS 2014].

Table 3-1. Some health conditions caused by active tobacco smoking

General disease category Site or specic health condition

Cancers Lung

Bladder

Esophageal

Laryngeal

Oral and throat

Cervical

Kidney

Pancreatic

Liver

Stomach

Colorectal

Acute myeloid leukemia

Cardiovascular disease Atherosclerosis

Coronary heart disease

Cerebrovascular disease (stroke)

Abdominal aortic aneurysm

Lung disease Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

Acute respiratory infections, including pneumonia

Asthma exacerbation

Tuberculosis

Asthmatic and other respiratory symptoms

Accelerated lung function decline

8 9

NIOSH CIB 67

•

Workplace Tobacco Policies NIOSH CIB 67

•

Workplace Tobacco Policies

General disease category Site or specic health condition

Reproductive eects Reduced fertility

Placental abnormalities

Ectopic pregnancy

Impaired fetal development and congenital orofacial

defects

Premature delivery

Low birth weight

Sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS)

Erectile dysfunction

Other diseases or conditions Cataracts, macular degeneration, and blindness

Low bone density and hip fractures

Poor wound healing

Peptic ulcer disease

Periodontitis

Diabetes

Rheumatoid arthritis

Impaired immune function

General poor health

Source: DHHS [2004, 2014]

Cancer

Smoking is estimated to cause nearly 164,000 can-

cer deaths among smokers each year in the United

States [DHHS 2014]. Cancers caused by smoking in-

clude lung, mouth, throat, bladder, and other cancers

(Table3-1). Among the carcinogens present in ciga-

rette smoke are polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons;

N-nitrosamines; aromatic amines; 1,3-butadiene;

benzene; aldehydes; and ethylene oxide. In addition

to directly causing cancer, smoking can synergistically

interact with occupational exposures known to sepa-

rately cause cancer, leading to eects on cancer cau-

sation greater than the eects of the two factors sepa-

rately [Wraith and Mengersen 2007; Frost et al. 2011;

Markowitz et al. 2013] (see Box 3-1).

Cardiovascular Disease

Cigarette smoking is estimated to cause nearly

125,000 heart disease deaths among smokers

each year in the United States [DHHS 2014]. e

constituents of tobacco smoke believed to be re-

sponsible for causing cardiovascular disease include

oxidizing chemicals, nicotine, carbon monoxide,

and particulate matter. Coronary heart disease

(ischemic heart disease) makes up the majority of

those heart disease deaths. Cerebrovascular disease

(vascular disease in the brain), which can cause

strokes, is also a major cause of death from smok-

ing. Smoking also causes aortic aneurysms and pe-

ripheral arterial disease. Smoking is estimated to

cause nearly 27,000 cerebrovascular and peripheral

vascular deaths among smokers each year in the

United States [DHHS 2014]. Even low levels of ex-

posure to tobacco smoke—such as a smoking only

a few cigarettes per day, occasional smoking, or ex-

posure to SHS—are enough to greatly increase risk

of cardiovascular events [DHHS 2010b].

Lung Disease

Cigarette smoking is estimated to cause more than

113,000 deaths among smokers each year in the

Table 3-1 (Continued). Some health conditions caused by active tobacco smoking

8 9

NIOSH CIB 67

•

Workplace Tobacco Policies NIOSH CIB 67

•

Workplace Tobacco Policies

United States from non-malignant lung diseases

[DHHS 2014]. Some of the chemical pathways by

which tobacco smoke produces lung damage have

been well characterized. It is likely that familial or

genetic factors inuence susceptibility to the ad-

verse eects of tobacco smoke. Chronic obstructive

pulmonary disease (COPD), a broad designation

encompassing bronchitis, emphysema, and airways

obstruction, accounts for most smoking-caused re-

spiratory deaths. As noted above, the eects of oc-

cupational exposure to agents that are toxic to the

lung can combine with the adverse health eects

of tobacco smoke to cause lung disease of greater

severity than that expected from either of the expo-

sures alone (see Box 3-2). Although smoking is the

single most common cause of COPD, occupational

exposures—oen combined with smoking—play a

role in causing about 10% to 20% of all COPD cases

[Balmes et al. 2003]. In addition, smoking causes

exacerbation of asthma, greater susceptibility to in-

fectious pneumonias, and higher risk of tuberculo-

sis [DHHS 2014].

Reproductive and Developmental Eects

Inhalation of tobacco smoke aects the reproduc-

tive system, with harmful eects related to fertil-

ity, fetal and child development, and pregnancy

outcome. Smoking is estimated to cause more

than 1,000 deaths from perinatal conditions each

year in the United States [DHHS 2014]. Exposure

to the complex chemical mixture of combustion

compounds in tobacco smoke—including carbon

monoxide, which binds to hemoglobin and can

deprive the fetus of oxygen—has been found to

contribute to a wide range of reproductive eects

in women. ese eects include altered menstrual

cycle and reduced fertility; placental abnormalities

and preterm delivery; reduced birth weight, still-

birth, neonatal death, and sudden infant death syn-

drome (SIDS) in their ospring; earlier and more

symptomatic menopause; and other eects [DHHS

2001, 2004, 2014; Soares and Melo 2008; Sadeu et

al. 2010]. Smoking by men causes erectile dysfunc-

tion [McVary et al. 2001; DHHS 2014], which can

also impair reproduction.

Box 3-1. Lung Cancer Risk in Insulators—Eects of Smoking, Asbestos Exposure, and Asbestosis

Cigarette smoking and exposure to asbestos are each well-known causes of lung cancer. Many studies

have assessed lung cancer risk among persons who have both smoking and asbestos exposure as risk

factors. Frost et al. [2011] conrmed the long-standing view that cigarette smoking raises the risk

of death from lung cancer among asbestos-exposed workers in a manner that is greater than addi-

tive, if not multiplicative. Results of the study by Markowitz et al. [2013] illustrate eects of smoking

combined not just with asbestos exposure, but also specically with asbestosis (a brotic lung disease

caused by asbestos). Markowitz et al. reported a long-term mortality study of 2,377 asbestos-exposed

insulators identied in 1967 and 54,243 contemporaneous blue-collar workers with little, if any, as-

bestos exposure. e insulators were divided into two subgroups—one with and the other with-

out radiographic evidence of asbestosis—with roughly equivalent asbestos exposure. Separate lung

cancer risks were 10.3-fold for smoking (without asbestos exposure), 3.6-fold for asbestos exposure

(without smoking), and 7.4-fold for asbestosis (without smoking). Combined lung cancer risks were

14.4-fold for smoking combined with asbestos exposure and 36.5-fold for smoking combined with

asbestosis. e former illustrates an apparent additive eect, because the combined eect was about

what would be expected by adding the separate risks for smoking and asbestos exposure. e latter

illustrates an apparent supra-additive (i.e., synergistic) eect, because the combined eect is substan-

tially greater than what would be expected by adding the separate risks for smoking and asbestosis.

10 11

NIOSH CIB 67

•

Workplace Tobacco Policies NIOSH CIB 67

•

Workplace Tobacco Policies

Other Adverse Eects

Smoking is known to cause other health problems

that contribute to the generally poorer health of

smokers as a group. ese include visual diculties

(due to cataracts and age-related macular degen-

eration), hip fractures (due to low bone density),

peptic ulcer disease, diabetes, rheumatoid arthritis,

and periodontitis [DHHS 2014] (Table 3-1). Smok-

ing may also cause hearing loss in adults [Cruick-

shanks et al. 1998].

Inammatory eects of tobacco smoke have

been associated with many other health ef-

fects. For example, smoking has been found to

delay wound healing aer surgery and lead to

wound complications [Sorensen 2012]. Also,

tobacco smoking may increase the risk of

hearing loss caused by occupational exposure

to excessive noise [Tao et al. 2013]. Research

on other health eects associated with ex-

posure to tobacco smoke will undoubtedly

provide a more complete understanding of the

adverse health eects of smoking.

Secondhand Smoke

In the United States, SHS exposure causes more

than 41,000 deaths among nonsmokers each year

[DHHS 2014]. ere is strong evidence of a causal

relationship between SHS of adults and adverse

health eects, including lung cancer, heart dis-

ease, stroke, exacerbation of asthma, nasal irrita-

tion, and (due to maternal exposure) reduced birth

weight of ospring (Table 3-2) [DHHS 2006, 2014;

IARC 2009; Henneberger et al. 2011]. e evidence

that exposure to SHS causes health eects among

exposed infants and children is also strong (Table

3-2)[DHHS 2006, 2014; IARC 2009].

ere is also suggestive evidence that exposure to

SHS causes a range of other health eects. ese

include respiratory diseases (asthma, COPD),

breast cancer, and nasal cancer among nonsmok-

ing adults, premature delivery of babies born to

women exposed to SHS, and cancers (leukemia,

lymphoma, brain cancer) among children exposed

to SHS [DHHS 2006, 2014; IARC 2009]. SHS ex-

posure may also be associated with hearing loss in

adults [Fabry et al. 2011].

Among nonsmoking adults, health risks of SHS

exposure extend to workplace exposures. A meta-

analysis of 11 pertinent studies provided quanti-

tative estimates of lung cancer risk attributable to

workplace exposure to SHS; lung cancer risk was

increased by 24% overall among workers exposed

to SHS in the workplace, and there was a doubling

of lung cancer risk among workers categorized as

highly exposed to SHS in the workplace [Stayner et

al. 2007]. A dramatic example of an adverse eect

of exposure to SHS in the workplace was an asth-

matic worker’s death (see Box 3-3).

Smokeless Tobacco

Some forms of smokeless tobacco are well docu-

mented as causes of oral cancer, esophageal cancer,

Box 3-2. Emphysema Risk in Coal Miners—Eects of Tobacco Smoking and Coal Mine Dust Exposure

A study [Kuempel et al. 2009] evaluated the eects of exposure to coal mine dust, cigarette smoking, and

other factors on the severity of lung disease (emphysema) among more than 700 deceased persons, including

more than 600 deceased coal miners. e study found that combined occupational exposure to coal mine

dust and cigarette smoking had an additive eect on the severity of emphysema among the coal miners.

Among smokers and never-smokers alike, emphysema was generally more severe among those who had

higher levels of exposure to coal mine dust. However, at any given level of dust exposure, miners who had

smoked generally had worse emphysema than miners who had not smoked.

10 11

NIOSH CIB 67

•

Workplace Tobacco Policies NIOSH CIB 67

•

Workplace Tobacco Policies

Box 3-3. Asthma Death and Exposure to Secondhand Smoke—A Case Report

On May 1, 2004, a 19-year-old part-time waitress, who had a history of asthma since childhood,

arrived at work. She spent 15 minutes chatting with a coworker in an otherwise unoccupied room

adjacent to the bar and was reported to have no apparent breathing diculty at that time. She then

entered the bar, which was occupied by dozens of patrons, many of whom were smoking. Less than 5

minutes later she reported to the manager that she wished she had her inhaler with her, needed fresh

air, and needed to get to the hospital. As she walked towards the door, she collapsed. An emergency

medical crew attempted resuscitation and transported her to a hospital emergency room, where she

was declared dead. “Status asthmaticus” and “asphyxia secondary to acute asthma attack’’ were the

causes of death recorded on the death certicate and autopsy report, respectively. e workplace was