MID-TERM PERFORMANCE EVALUATION OF

THE STRENGTHENING VALUE CHAINS (SVC)

ACTIVITY IN THE DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC

OF THE CONGO

January 15, 2021

MID-TERM PERFORMANCE EVALUATION OF

THE STRENGTHENING VALUE CHAINS (SVC)

ACTIVITY IN THE DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC

OF THE CONGO

January 15, 2021

Prepared for the United States Agency for International Development under USAID Contract Number:

AID-OAA-TO-16-00008

Submitted to:

USAID/DRC

Carter Hemphill

chemphill@usaid.gov

and

USAID/Bureau for Resilience and Food Security

Lesley Perlman

Submitted by:

Della E. McMillan, Team Leader

James L. Seale, Jr., Agriculture Specialist/Value Chain Expert

Christopher Coffman, Evaluation Specialist

Dieudonné Bahati Shamamba, Agricultural Specialist

Dora Muhuku Salama, Gender, SBCC and Capacity Building Specialist

Pascal Kaboy Mupenda, Evaluation Field Coordinator

Contractor:

Program Evaluation for Effectiveness and Learning (PEEL)

ME&A

1020 19

th

Street NW, Suite 875

Washington, DC 20036

Tel: 240-762-6296

Recommended citation:

Della E. McMillan, James L. Seale, Jr., Dieudonné Bahati Shamamba, Dora Muhuku Salama, Pascal Kaboy

Mupenda, Christopher Coffman. 2020. Mid-Term Performance Evaluation of the Strengthening Value

Chain (SVC) Activity in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Bethesda, Md. Program Evaluation for

Effectiveness and Learning (PEEL) for USAID/DRC.

Photo Credit: Woman’s hands holding beans (left). Woman sorting coffee beans (right). Photo by Lucy

O’Bryan Photography. Images used with the permission of Tetra Tech.

DISCLAIMER

The authors’ views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States

Agency for International Development or the United States Government.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The evaluation team (ET) would like to express its deep gratitude to the Strengthening Value Chain

Activity (SVC) team for its stolid backup at every stage of this evaluation.

SVC M&E Director, Ruben Bahavu Bihango provided strong back-up and helped develop simple tables that

distilled the activity’s considerable achievements. Special thanks are also due to Hubert Nkaotuli, Finance

Specialist, for providing summary tables on finance. In addition to accompanying the team on its initial pilot

testing of the forms, Gender Specialist Bertin Bisimwa Kabomboro provided reams of documents and

special tables on the SVC Gender Action Learning System (GALS) strategy that were much appreciated.

The ET would also like to extend a special note of gratitude to the Chief of Party’s principal assistant,

Guilain Kulimushi, who played a vital role in helping the Evaluation Field Coordinator, Pascal K. Mupenda,

track down hundreds of missing telephone and email addresses and initiate contact with the people to

explain who we were and why we wanted to interview them.

The ET would also like to thank its local partner, Research Initiative in Social Development (RISD), and

its Managing Director Emmanuel Kandate Musema and Senior Researcher Antoine Mmushagalusa Ciza.

We would also like to thank RISD Field Supervisor Rodrigue Salomona Bagabo who verified field

appointments and non-respondents to the initial invitation for online survey.

We also want to thank the USAID staff who played a key role in in this study. We are especially grateful

to the SVC Contracting Officer’s Representative Carter Hemphill and the SVC Agreement Officer’s

Representative Augustin Ngeleka who is the institutional memory for this activity and the Kivu Agriculture

and Nutrition Shared Results Framework and all of the previous agriculture and economic growth projects

that preceded SVC. Finally, we would like to thank Lesley Perlman at the Bureau for Resilience and Food

Security for her firm support throughout this process.

One of the things that made this exercise very different from a conventional Feed the Future evaluation

was the wide participation and support it enjoyed from other USAID program staff and funded projects.

For this we are grateful to the leadership of Marialice Ariens, the USAID/DRC Food for Peace Advisor,

and her team Marcel Ntumba and Dieudonne Mbuka and DFSA leaders like Anthony Koomsom, Dr.

Claude Nankam, and Filbert Leone Ahmat at Food for the Hungry and Jean Daniel at Mercy Corps.

The team also wishes to thank the PEEL staff who backstopped us down to the very end, especially Dr.

Gary Woller, PEEL Chief of Party; Lidia Awad, Senior Project Coordinator; Michelle Ghiselli, ME&A Senior

Editor; and Jessica Drew, Assistant Project Coordinator.

ABSTRACT

The USAID/Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) Strengthen Value Chain Activity (SVC) activity aims to

increase agricultural production and incomes of small farmers in the dried bean, soybean, and coffee value

chains (VCs) in the DRC’s South Kivu province. The SVC mid-term performance evaluation sought to

identify achievements, performance issues, and constraints, focusing on SVC’s collaboration with Food for

Peace (FFP) and, from this, to identify a set of actionable recommendations to achieve activity goals and

objectives for the short, medium, and long-term.

Activity interventions contributed to the increased adoption of improved production and post-harvest

practices and increased production, quality, and sales, and to a lesser extent increased market linkages, in

the dried bean and coffee VCs. SVC’s gender activities further contributed to the increased adoption of

gender practices and gender outcomes by small farmers and their POs. However, numerous challenges

remain in the targeted VCs, chief among them the lack of access to quality inputs and finance, lack of

horizontal and vertical market linkages, and weak capacity of farmer producer organizations (POs).

SVC has struggled to achieve an integrated “one-team” approach with the FFP Development Food Security

Activities (DFSAs) owing to, among other things, different intervention priorities, contractual restrictions,

weak intra-project communication, and poor synchronization of implementation timelines.

The evaluation offers nine primary recommendations and 25 sub-recommendations for USAID/DRC

related to staffing and management, capacity building, access to inputs, access to finance, market

diversification, strengthening the enabling environment, inter-project coordination, gender, youth, and

social engagement, and strengthening VC best practices.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................................................................................................... i

1.0 EVALUATION OVERVIEW .................................................................................................................................. 1

1.1 Evaluation Purpose and Audience ........................................................................................ 1

1.2 Evaluation Questions ......................................................................................................... 1

2.0 ACTIVITY BACKGROUND ................................................................................................................................. 1

2.1 Mechanism Description ...................................................................................................... 1

2.1.1 Context ............................................................................................................... 1

2.1.2 Target Populations and Areas ................................................................................ 2

2.1.3 Activity Implementation Plan ................................................................................. 3

3.0 EVALUATION METHODS AND LIMITATIONS ............................................................................................ 5

3.1 Data Collection Methods ................................................................................................... 6

3.2 Methodological Limitations ................................................................................................. 6

4.0 FINDINGS & CONCLUSIONS ............................................................................................................................ 7

4.1 EQ 1: To what extent is SVC meeting overall intended goals and objectives? ......................... 7

4.1.1 How can Tetra Tech improve its implementation and management approach to better

achieve results toward objectives? .......................................................................... 7

4.1.2 What are the notable areas of progress the activity has achieved in support of activity

objectives? .......................................................................................................... 10

4.1.3 Conclusions ....................................................................................................... 20

4.2 EQ 2: In what ways has SVC’s collaboration with other USAID activities effectively contributed

to the Sub-IRs in the Shared Results Framework and the Shared Contract Target? .............. 21

4.2.1 What are some of the difficulties the activity has faced coordinating activities? ........ 21

4.2.2 For which Sub-IRs has the collaboration been most effective? ................................ 24

4.2.3 Are the results different between sites where collaboration has occurred versus sites

where SVC has been working independently? ........................................................ 24

4.2.4 How can the collaboration and identified gaps be improved? .................................. 25

4.2.5 Conclusions ....................................................................................................... 26

4.3 EQ 3: To what extent did SVC address the issue of increased gender equality and increased

women’s economic empowerment in target communities? .................................................. 26

4.3.1 What approaches have been most effective? ......................................................... 26

4.3.2 How can SVC more effectively integrate cross-cutting sectors and gender

considerations into interventions? ........................................................................ 30

4.3.3 Conclusions ....................................................................................................... 31

4.4 EQ 1-C: What are some of the challenges faced in meeting the intended goals, objectives, and

results? How effectively has the implementer dealt with those challenges? What can be changed

to better meet goals and objectives? / EQ 4: What are the internal and external threats to

sustainability beyond the life of the activity for the following components of SVC? What are the

biggest challenges that need to be addressed? What opportunities are there for the Mission to

better ensure sustainability? ............................................................................................. 31

4.4.1 Primary challenges and threats to Coffee and Agriculture/Agribusiness Sectors ....... 31

4.4.2 Predictable and unpredictable challenges and threats ............................................. 33

4.4.3 Component 1: Build capacity of vertical and horizontal actors in targeted VCs ........ 34

4.4.4 Component 2: Enhance coffee production ............................................................ 36

4.4.5

Component 3: Develop and implement public private partnerships ......................... 36

4.4.6 Component 4: Access to Finance (A2F) ................................................................ 37

4.4.7 Cross-Cutting Intermediate Result (CCIR): Gender, Youth, and Social Inclusion ...... 37

4.4.8 Capacity Building Assistance ................................................................................ 38

4.4.9 Conclusions ....................................................................................................... 39

4.5 EQ 5: What considerations should USAID/DRC consider in the future design of

Agriculture/EG Activities, particularly in regard to the IRs of the Shared Results Framework? . 40

4.5.1 IR 1: Improved agricultural livelihoods .................................................................. 40

4.5.2 IR 2: Expanded markets and trade ........................................................................ 41

4.5.3 IR 3: Improved uptake of essential nutrition behaviors and services ........................ 43

4.5.4 CCIR: Gender equality and social empowerment (SBCC and conflict mitigation) ..... 44

4.5.5 Improved collaboration with other USAID-funded projects ................................... 44

4.5.6 Conclusions ....................................................................................................... 45

5.0 RECOMMENDATIONS .................................................................................................................................. 46

6.0 ANNEXES .......................................................................................................................................................... 50

Annex 1: Evaluation Questions ........................................................................................... 51

Annex 2: Summary Recommendations for the Current Life of Activity and Any Costed Extension

(*Indicates Activities That Will Require a Costed Extension) ................................... 53

Annex 3: Components and Partners by Territory ................................................................. 59

Annex 4: Nested Market Networks Collaborating With SVC ................................................ 60

Annex 5: Qualitative and Quantitative Data Sources for the Seven Categories of SVC Stakeholders

.......................................................................................................................... 64

Annex 6: Performance Indicator Tracking Table ................................................................... 65

Annex 7: Apex Groups and Producer Organizations in South Kivu ........................................ 73

Annex 8: Concessionaire Partners of SVC ........................................................................... 75

Annex 9: Apex Groups and Concessionaries Working on Soybeans Possibly Targeted for Support

in FY 2021 and FY 2022 ....................................................................................... 76

Annex 10: Evolution of SVC Support for Different Types of Finance (Through June 30, 2020) . 78

Annex 11: GALS Training Participants ................................................................................. 79

Annex 12: List of Stakeholders Interviewed ......................................................................... 82

Annex 13: Bibliography ...................................................................................................... 93

Annex 14: SVC Mid-Term Performance Evaluation Expression of Interest .............................. 95

Annex 15: Conflict of Interest Forms for ET Members ....................................................... 105

LIST OF TABLES

Table 1: Adoption of Improved Agricultural Practices in the Coffee VC (N=54) ........................................... 11

Table 2: Increased Use of Agricultural Production Inputs in the Coffee VC (N=54) ..................................... 12

Table 3: Adoption of Post-Harvest Practices in the Coffee VC (N=54) ............................................................ 13

Table 4: Market Linkage Outcomes in the Agriculture and Agribusiness VCs (N=120) ............................... 18

Table 5: Post-Harvest Outcomes in the Agriculture and Agribusiness VCs (N=120) ................................... 19

Table 6: Comparison of Outcomes for Dried Bean Farmers in North Kalehe and South Kalehe (N=432)

............................................................................................................................................................................. 25

Table 7: Effectiveness of GALS in Promoting Gender Outcomes ....................................................................... 29

Table 8: Perceived Sustainability of SVC Impacts – Online Survey Respondents (N=183) ........................... 32

Table 9: Primary Challenges and Threats – CATI Survey Respondents ............................................................ 32

Table 10: Primary Challenges and Threats – Online Survey Respondents ........................................................ 33

Table 11: Perceived Usefulness of SVC Capacity Building Assistance (N=26) ................................................. 38

Table 12: Evolution of DFSA VC Priorities Over the Life Cycle of a Five-Year Activity and Opportunities

for Market Systems Engagement in Three Predictable Time Frames ................................................ 45

LIST OF FIGURES

Figure 1: Kivu Agriculture and Nutrition Shared Results Framework (2013) .................................................... 2

Figure 2: FTF SVC and FSP Locations ........................................................................................................................... 4

Figure 3: Co-Location Areas Between FSP and SVC Activities .............................................................................. 5

Figure 4: Trajectory of Dried Bean Sales Prices by Season and Territory ($US per Kilogram) ................... 16

LIST OF ACRONYMS

ACRONYM

DESCRIPTION

A2F

Access to Finance

ACT

Association of Small Cross-Border Traders

AMELP

Activity Monitoring, Evaluation, and Learning Plan

AMSA

Association des Multiplicateurs de Semences Améliorées

AOR

Agreement Officer’s Representative

ASOP

Action Sociale et d’Organisation Paysanne

AVEC

Associations Villageoises d'Épargne et de Crédits

B2B

Business to Business

CARG

Rural Agricultural Management Council

CATI

Computer-Assisted Telephone Interview

CBG

Community-Based Group

CCIR

Cross-Cutting Intermediate Result

CCKa

Kalehe Coffee Cooperative

CDCS

Country Development Cooperation Strategy

CDO

Community Development Officer

CFC

Coffee Farmer College

CLD

Communauté Locale de Développement

CMC

Community Marketing Center

COP

Chief of Party

COR

Contracting Officer’s Representative

COVID-19

Coronavirus Disease 2019

CPCK

La Coopérative des Producteurs du Café de Kabamba

CPEs

Concessionaires and Private Enterprises

CPR

Centre de Promotion Rurale/ Idjwi

CSP

Coffee Service Provider

CTAs

Collaborators and Technical Assistance Providers

DCA

Development Credit Authority

DFSA

Development Food Security Activity

DRC

Democratic Republic of the Congo

DTS

Deconcentrated Government Services

EG

Economic Growth

EQ

Evaluation Question

ET

Evaluation Team

ETD

Entité Territoriale Décentralisée

FBG

Farmer Business Group

FEC

Federation of Businesses of the Congo

FFP

Food for Peace

FFS

Farmer Field School

FGD

Focus Group Discussion

FH

Food for the Hungry

FI

Financial Institution

FODDR

Fondation Djuma Dominique Rwesi

FSP

Food Security Project

FTF

Feed the Future

FY

Fiscal Year

GALS

Gender Action Learning System

GAP/K

Groupe Agricole Pastorale/Kivu

ACRONYM

DESCRIPTION

GDRC

Government of the Democratic Republic of the Congo

GYSI

Gender, Youth, and Social Inclusion

ha

Hectare

HQ

Headquarters

IA

Inter-Association

IGA

Integrated Governance Activity

IHP

Integrated Health Project

INERA

National Agricultural Study and Research Institute

IP

Implementing Partner

IR

Intermediate Result

IYDA

Integrated Youth Development Activity

KACCO

Kalehe Arabica Coffee Cooperative

kg

Kilogram

KII

Key Informant Interview

km

Kilometer

LC

Listening Club

LOA

Life of Activity

M&E

Monitoring and Evaluation

MC

Mercy Corps

ME&A

ME&A, Inc.

MECC

Monitoring, Evaluation, Coordination, Contract

MFI

Microfinance Institution

MIS

Market Information System

MOU

Memorandum of Understanding

MSMEs

Micro, Small, and Medium-Sized Enterprises

MT

Metric Ton

OFTT

On-Farm Technical Trial

ONAPAC

Office Nationale des Produits Agricoles

PACE

Participatory Agricultural Cascade

PAV

Programme d’Appui aux Vulnérables

PEEL

Program Evaluation for Effectiveness and Learning

PHH

Post-Harvest Handling

PITT

Performance Indicator Tracking Table

PO

Producer Organization

POSA

Producer Organization Sustainability Assessment Tool

PPP

Public-Private Partnership

RCPCA

Réseau des Coopératives des Producteurs de Café Cacao en RDC

RFS

Bureau for Resilience and Food Security

RISD

Research Initiative for Social Development

SBCC

Social and Behavior Change Communication

SCPNCK

Société Coopérative des Producteurs Novateurs du Café au Kivu

SFCG

Search for Common Ground

SIL

Soy Innovation Lab

Sub-IR

Sub-Intermediate Result

SVC

Strengthening Value Chains Activity

TA

Technical Assistance

TIP

Trafficking in Persons

TO

Transition Objective

TOT

Training of Trainers

UCB

Catholic University of Bukavu

ACRONYM

DESCRIPTION

UCOAKA

Union des Coopératives Agricoles de Kalehe

UO

Umbrella Organization

USAID

United States Agency for International Development

USG

United States Government

VC

Value Chain

VSLA

Village Savings and Loan Association

WCR

World Coffee Research

WV

World Vision

ZOI

Zone of Influence

i

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

INTRODUCTION

This Executive Summary presents an overview of the findings, conclusions, and recommendations from

the midterm performance evaluation of the Feed the Future, Democratic Republic of the Congo,

Strengthening Value Chains (SVC) Activity. The evaluation’s purpose is to identify achievements,

performance issues, and constraints related to activity implementation and effectiveness, with a focus on

SVC’s collaboration with Food for Peace (FFP) in the same geographical zone, and, from this, to identify a

set of actionable recommendations to achieve activity goals and objectives for three time horizons—

short-term (one to two years); medium-term (three to four years); and long-term (greater than five years).

ACTIVITY BACKGROUND

In 2013, the United States Agency for International Development Democratic Republic of the Congo

(USAID/DRC) Country Development Cooperative Strategy (CDCS) committed USAID to support a new

model of integrated regional transition planning for Eastern Congo designed to shift assistance focus away

from humanitarian relief toward a market-led development as articulated in CDCS Transition Objective

(TO) 3. To achieve TO 3, USAID developed a regional strategy in which USAID-funded activities in South

Kivu would collaborate with one another to achieve the three principle objectives of the Kivu Agriculture

and Nutrition Shared Results Framework. SVC was originally conceptualized as one of three categories

of USAID-funded activities to achieve the Kivu Agricultural and Nutrition Shared Objective, “Reduce

extreme poverty and malnutrition in target populations.” The two other categories of programming included

the two FFP projects known as Development Food Security Activities (DFSAs) and other USAID-funded

projects that were active in the area. SVC’s stated purpose is to “increase household incomes and access to

nutrient-rich crops by linking smallholder farmers to strengthened and inclusive value chains and supportive market

chain services.”

Tetra Tech implements SVC in collaboration with five implementing partners (IPs): Banyan Global, J.E.

Austin Associates, Inc., Search for Common Ground (SFCG), TechnoServe, and World Coffee Research

(WCR). Together they work to build the capacity of vertical and horizontal actors working within the

dried bean, soybean, and coffee value chains (VCs) in the South Kivu territories of Kabare, Kalehe, and

Walungu. Contractually, SVC’s assistance to the dried bean and soybean VCs is limited to post-harvest to

market activities, while its assistance to the coffee VC covers the entire VC.

SVC is organized around six components: 1) build capacity of vertical and horizontal actors in targeted

VCs; 2) enhance coffee production; 3) develop and implement public-private partnerships (PPPs);

4) enhance access to finance; 5) gender, youth, and social inclusion (GYSI); and 6) social and behavior

change communication (SBCC) and resilience. The component teams were expected to work with the

DFSAs and other USAID projects to benefit diverse actors, including the provincial, territorial, and local

governments, producer organizations (POs), cooperatives, agro-dealers, concessionaires (large

landholders), collection centers, warehouses, wet mills, buyers, financial institutions (FIs), and smallholder

farmers. By June 2020, SVC was working with 45,291 direct beneficiaries, 50 percent more than its

contractual target of 30,000, and 61,000-92,000 indirect beneficiaries.

EVALUATION DESIGN AND LIMITATIONS

The evaluation sought to answer five primary evaluation questions (EQs) using a mixed-methods

evaluation design consisting of a document review; a review of SVC’s performance monitoring data;

133 key informant interviews (KIIs) and focus group discussions (FGDs) with 292 participants across six

primary stakeholder groups; an online survey with 183 respondents across the same six stakeholder

groups; and a computer-assisted telephone interview (CATI) survey with 800 smallholder farmers

benefiting from activity production and post-harvest handling (PHH) support in the dried beans and coffee

ii

VCs and 203 farmers participating in SVC’s Gender Action Learning System (GALS) trainings. Because of

government bans on travel outside of Bukavu, the evaluation team (ET), consisting of two international

consultants and three local consultants, conducted only 23 of their KIIs/FGDs in person and the rest using

remote interviewing methods, including telephone, Skype, Google Meet, and Zoom.

The SVC evaluation design included a number of methodological limitations. The principal limitation was,

due to the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, the two international consultants were not

able to conduct field visits. The ET sought to minimize the impact of this limitation by taking additional

time to develop and refine the KII/FGD protocols and train the team in their use and adopting a

participatory process for decentralized management under the leadership of a qualified field coordinator.

Other limitations included the challenges involved in identifying and selecting participants in the KIIs and

FGDs and the two surveys both to minimize bias and ensure the independence of the evaluation. To

address these challenges, the ET collaborated closely with SVC to generate comprehensive lists (or

sampling frames) of stakeholders and then to either purposively (KIIs, FGDs, and online survey) or

randomly (CATI survey) select key informants to participate in the evaluation. The ET employed a variety

of processes to ensure that the selection process (responses) was as representative as possible.

Notwithstanding, the degree of female representation on the CATI survey fell below targets owing to

lower ownership/control of mobile phones by females compared to males.

FINDINGS AND CONCLUSIONS

EQ 1: To what extent is the SVC meeting intended goals and objectives?

Findings

How can Tetra Tech improve its implementation and management approach to better

achieve results toward objectives? Key informants praised Tetra Tech’s flexible management

approach, which enabled it to make progress towards its objectives in the face of several major challenges.

Implementation challenges that SVC has faced are as follows:

∉ Difficulty developing a “one team” approach with the IPs because of SVC’s requirement to create and

report on IP component teams, which encouraged the teams to develop their own work plans in silos

before consolidation in a master work plan for execution and reporting by component teams.

∉ The common perception among activity stakeholders that SVC failed to incorporate local actors and

local concerns in activity planning and interventions, notwithstanding SVC’s efforts to involve local

partners it its annual planning and implementation activities.

∉ Misaligned provisions in the SVC contract and the DFSA cooperative agreements, which meant that

the DFSAs focused on different VCs than SVC, limited SVC to working on half the VC in the dried

bean and soybean VCs while providing full support for the specialty coffee VC, and adversely affected

SVC’s ability to backstop the DFSAs in developing the private sector seed supply needed to sustain

higher production levels.

∉ Lack of field staff, which affected SVC’s ability to provide the level of service required. This, together

with the above contractual requirement, made it difficult for SVC to support some emerging

community and DFSA initiatives and kept it tied to the soybean VC.

∉ Project contracts that did not include guidance on monitoring and reporting on joint activities.

∉ Most support for intra-project coordination with the DFSAs and other USAID projects in South Kivu

stopped after the security situation worsened in Fiscal Year (FY) 2018.

iii

What are the notable areas of progress the activity has achieved in support of activity

objectives?

Coffee Value Chain: Senior staff at USAID, SVC, the DFSAs, and other USAID projects cited the

successful scale-up of the SVC coffee model as SVC’s biggest success story. Notable areas of progress in

the coffee VC include:

Intermediate Result (IR) I: Improved agricultural livelihoods among targeted households: Eighty-seven

percent of coffee farmer college (CFC) participants in the CATI survey reported their coffee production

increased by a large or very large extent, and 67 percent increased their coffee sales to a large or very

large extent. FGD participants agreed that SVC is very effective in improving coffee production through

the CFC, while 94 percent of online survey respondents agreed that the quality of their coffee cherry had

improved after participating in the CFC. KII and FGD participants noted improvements in outcomes

related to production, quality, sales, and income.

Sub-Intermediate Result (Sub-IR) 1.1: Increased use of improved agricultural practices and inputs: Ninety-

two percent of CATI survey CFC participants said they implemented what they learned from the training

either to a large extent or very large extent. More than 90 percent of online survey farmer trainers and

focal farmers agreed that coffee farmers had adopted improved weeding, pest management, rejuvenation,

and pruning practices and increased the quality of their coffee production because of CFC.

IR 2: Expanded markets and trade: SVC helped POs, concessionaires, and private enterprises to access

credit and training to develop washing station infrastructure and quality control measures needed to be

competitive in international markets; attracted roasters to the Saveur du Kivu trade show and improved

the cupper training; targeted and monitored PO capacity building for managing washing stations; facilitated

the creation of the Network of Cocoa Coffee Producers Cooperatives in the DRC (RCPCA), the principal

national platform for coffee producers in the country; and encouraged a better enabling environment.

Sub-IR 2.1: Improved market linkages and information systems: Activity internal tracking shows more

revenue per kilogram of exportable green and an upward trend in initial and second payments in the

percentage of the final price accruing to farmers. Tracking also shows an increase in the number of

containers of specialty coffee exported per year from South Kivu in the number of specialty coffee buyers.

Sub-IR 2.2: Improved post-harvest storage and processing: Ninety percent of online survey respondents

reported increased adoption of improved post-harvest practices. According to stakeholder interviews,

SVC was successful in relation to post-harvest practices and infrastructure.

Sub-IR 2.3: Improved access to finance: SVC surpassed its targets for increasing private sector investment

in the specialty coffee VC. SVC has provided basic training, retraining, and coaching that have increased

the FIs’ willingness and ability to make loans. To facilitate concessionaires’ co-investment in the target

VCs, SVC has provided SVC technical staff advice on improved agricultural practices and inputs and helped

develop the business plans they need to get credit.

Sub-IR 2.4: Increased capacity of agricultural-related producer groups, organizations, and enterprises: SVC

scaled up support to cooperatives and private enterprises managing the coffee washing stations from nine

in FY 2018 to 19 in FY 2020 managed by 15 operators, seven cooperatives and eight private enterprises.

Five cooperatives have reached the minimum level of capacity that they need to operative effectively, and

five cooperatives are managing the washing station satisfy SVC’s criteria for sustainability.

Sub-IR 2.5: Improved government service regulations and taxation for agricultural inputs and trade: Four

stakeholder interviews commended SVC for improving the global enabling environment for specialty

coffee production.

Sub-IR 3.2: Increased awareness of and commitment to essential nutrition promoting practices/Sub-IR 3.4:

Improved access to diverse and nutritious foods: SVC contributed to increasing the awareness of and

access to diverse and nutritious foods in the areas where it supports the specialty coffee VC by

iv

broadcasting SBCC radio spots promoting the consumption of dried beans and soybean products on seven

rural radio stations that were monitored by 19 community-based listening groups.

Cross-Cutting Intermediate Result (CCIR): Gender, youth, and social inclusion: SVC integrated messages

on gender and youth inclusion in all its PO and CFC trainings, developed a GALS course for CFCs, and

incorporated a gender module in the core training for 13,089 CFC participants. Sixty-four percent of CFC

online survey respondents agreed that SVC contributed to improving gender equity and women’s socio-

economic empowerment.

Addressing community development needs: SVC held training for 160 coffee farmers on GALS, increasing

their access to knowledge, inputs, and financing for washing stations needed to diversify into specialty

coffee production and making available more land for bean production.

Dried Bean Value Chain: In January 2020, SVC signed capacity building memoranda of understanding

(MOUs) with 10 platform/apex organizations working in the VC, including apex groups working with the

bean and soybean POs, principal apex organizations working with the bean and soybean sellers, and

Association of Small Cross-Border Traders (ACT). Notable areas of progress include:

IR 1: Improved agriculture livelihoods among targeted households: Thirty-nine percent of CATI survey

bean farmers reported that they received some production training, 91 percent of whom reported that

this production training had a positive impact on sales. Prices have increased since 2018 because of higher

product quality, the market linkages facilitated by SVC, and aggregation at the point of sale. Seventy-eight

percent of bean farmers reported receiving higher bean prices than the previous year. Twenty-five

stakeholder interviews cited instances in which activity assistance had contributed to improved dried bean

production, quality, sales, and income.

Sub-IR 1.1: Increased use of improved agriculture practices and inputs: An internal study found yields of

350 to 450 kilograms per hectare (kg/ha) on activity beneficiaries’ plots versus 1,025 kg/ha or higher on

demonstration plots, a result of weak access to improved seed and inputs, low adoption of improved

production practices, and limited application of fertilizers required due to low soil fertility. Only

48.3 percent of online respondents agreed or strongly agreed that farmers had increased their access to

quality inputs. The lack of access to inputs was cited as a persistent challenge across multiple KIIs/FGDs

and stakeholder groups. More positively, 86 percent of dried bean farmers in the CATI survey are

implementing their DFSA-supported production training in their fields, 96 percent have improved their

bean production, and 99 percent want to increase their bean production. In the online survey, 74.1 percent

of respondents agreed or strongly agreed that farmers had increased their product quality.

Sub-IR 2.1: Improved market linkages and information systems: Fifty-five percent of online survey

respondents reported that farmers had increased their number of commercial linkages or their access to

market information. Thirty stakeholder interviews cited forming new market linkages. More

concessionaires are facilitating leveraged sales for the beans grown adjacent to their concessions.

Sub-IR 2.2: Improved post-harvest storage and processing: Twenty-eight percent of CATI bean farmers

received formal post-harvest training, of which 86 percent reported implementing the training, 84 percent

said the training positively affected their production, and 82 percent said the training positively affected

their dried bean sales. Nearly 60 percent of online survey respondents reported that farmers had adopted

improved post-harvest practices. One-third of trained POs between 2018 and 2020 produced 27 percent

more beans for market.

Sub-IR 2.3: Improved access to finance: SVC helped leverage $3,169,630 in loans for SVC clients in the

coffee sector from FY 2017 through June FY 2020, principally to washing stations. The number of loans

from FIs with Development Credit Authority (DCA) loan guarantees increased from six in FY 2017 to 35

through June of FY 2020, albeit with the majority going to large agribusinesses. As of June 2020, 12 SVC-

supported concessionaires are working to receive (or have already received) loans for large infrastructure

investments, such as washing stations.

v

Sub-IR 2.4: Increased capacity of agriculture-related producer groups, organizations, and enterprises: Fifty-

two percent of POs included in SVC’s internal PO Sustainability Assessment Tool (POSA) survey had

attained the target of 61 percent of the basic capacity needed to organize group sales and member services.

Sub-IR 3.2: Increased awareness of and commitment to essential nutrition promoting practices: Ninety-

four percent of CATI survey respondents answering the question said that SVC’s SBCC messages were

incorporated into the PHH training and had increased their awareness of the nutritional benefits of

consuming biofortified beans. Further, 18 community-based stakeholder interviews stated that SVC SBCC

messaging on the radios had made them more aware of the health benefits of soybeans and dried beans.

Sub-IR 3.4: Improved access to diverse and nutritious foods: Twenty-one percent of CATI survey bean

farmers said they grew beans for household consumption, while 63 percent grew beans for both

household consumption and for sale. Bean farmers reserved 50.6 percent of their bean crop for home

consumption. SVC facilitated access to biofortified seeds for 6,800 of the most vulnerable households.

CCIR: Gender, youth, and social inclusion: Sixty percent of online survey respondents agreed that gender

equity and women’s socio-economic empowerment had improved in the agricultural and agribusiness

sectors, while 50.9 percent agreed that social inclusion had improved.

Soybean Value Chain: Since 2018, SVC has used the half VC strategy for the soybean VC to support

smallholders’ production of and access to soybeans. Soybean activities have included the following:

Sub-IR 1.1: Increased use of improved agricultural practices and inputs: SVC launched a public awareness

campaign to generate demand for improved bean and soybean seed; undertook missions to identify POs

interested in soy production; produced a cost of product study; and developed a handout of recommended

timing for agricultural inputs.

IR 2: Expanded markets and trade: SVC has conducted special studies of storage practices; explored and

facilitated institutional market opportunities to develop market linkages with SVC-supported POs and

concessionaires; facilitated linkages between local producers to supply local processors and buyers;

supported training in post-harvest processing and marketing; developed a fact sheet on soybean

production for banks and microfinance institutions (MFIs); and organized business to business (B2B) events

to promote soybean seed sales.

IR 3: Improved uptake of essential nutrition behaviors and services: SVC has promoted the nutritional

value of producing and consuming soybean products and supported SBCC radio spots. Ninety-three

percent of community-based producer groups who responded to the mini-survey on SBCC messaging

said that SVC’s investment in promoting soy had increased their interest in growing and consuming it.

Conclusions

SVC’s contract restrictions and budget adversely affected its ability to support the collaboration with

other projects needed to scale up initiatives. Promoting more or more effective coordination will require

better mechanisms for joint planning, execution, and co-reporting and reinstating some of the original

coordination mechanisms that USAID proposed.

SVC’s coffee strategy is increasing community-based stakeholders’ access to more diversified sources of

income by linking them to the specialty coffee VC. These activities are strengthening social inclusion by

facilitating women’s and youth’s access to CFC training and facilitating farmers’ access to nutritious foods.

SVC’s capacity building efforts are encouraging bean farmers in POs to consider additional investment in

yield-increasing production practices and strengthening smallholders’ access to dried beans for home

consumption.

Despite SVC’s efforts to promote soybean production, the scale-up and impact of these efforts has been

limited due to many of the same issues constraining dried bean sales, including low crop productivity and

vi

limited access to higher-yielding seeds. Nonetheless, there is emerging interest in promoting soybean

production and processing in community-based bean producer groups because of SVC’s promotion.

EQ 2: In what ways is SVC’s collaboration with other United States Government (USG)

activities effectively contributing to the Sub-IRs in the shared results framework and the

shared contract target?

Findings

What are some of the difficulties the activity has faced coordinating activities? Collaboration

between USG-funded activities in the three locations for the achievement of the 13 Sub-IRs in the shared

results framework has been difficult because of 1) the lack of USAID backstopping for expected TO 3

collaboration; 2) the delayed and difficult start-up of other USAID-funded projects; 3) the lack of

synchronization with the DFSAs who were expected to be SVC’s principal partner in the dried bean and

soybean VCs; and 4) SVC’s lack of territory-level offices or territory-based staff.

For which Sub-IRs has the collaboration been most effective? There has been effective formal

collaboration and informal areas of overlap between SVC and the two DFSAs, most notably in the dried

bean VC where SVC is providing assistance contributing to IR 1 and Sub-IRs 1.1, 2.1, 2.2, and 2.4, including

training the Food Security Project DFSA bean/soybean POs in post-harvest processing and collaboration

on GALS training. Successful formal collaboration includes training of DFSA staff on building PO capacity

on market principles and warehouse management, technical assistance (TA) for DFSA activities, GALS

training of DFSA staff and DFSA-supported village savings and loan association (VSLA) community agents,

and training for DFSA staff on helping POs access finance from MFIs and banks. Informal areas of overlap

include PO members attached to SVC-supported apex organizations that also work with the DFSAs,

geographical overlap between SVC and the DFSAs, CFC participants who also participate in DFSA

activities, overlapping participation in SVC POs and trainings between DFSA members and former

Development Food Assistance Program (DFAP)-supported VSLAs, and women beneficiaries of SVC who

are members of a DFSA VSLA, PO, or youth group.

Are the results different between sites where collaboration has occurred vs. sites where SVC

has been working independently? The DFSAs’ decision not to support soybean weakened the impact

of SVC’s efforts to link the most active concessionaires and cooperatives that wanted to develop their

soybean production to reliable national and international markets. While this overlap and collaboration

between SVC and the DFSAs helped in some cases, it was less effective in areas that graduated from

humanitarian aid and are no longer chronically food insecure.

How can the collaboration and identified gaps be improved? Stakeholder recommendations for

improving collaboration gaps, included better communication with the DFSAs, formal protocols for

collaboration with the DFSAs, a shared beneficiary database, grants for initiatives that strengthen VC

activities to encourage local banks to take an interest in POs and apex organizations, permission for SVC

to provide more support to dried bean and soybean production and other VCs, and new mechanisms to

ensure coordination between Feed the Future and FFP Contracting Officer’s Representatives/Agreement

Officer’s Representatives (COR/AORs) and DRC Mission staff.

Conclusions

SVC has not built the formal collaboration with the DFSAs envisioned in SVC’s original contract, but their

collaboration can complement the DFSAs’ investment to contribute to the achievement of the higher-

level goals in the shared results framework.

Many DFSA beneficiaries are becoming less food insecure, allowing them to invest in VC activities that

overlap with SVC post-harvest training and market linkages activities, which has linked smallholder farmers

to stronger VC activities and supportive market services. A primary challenge will be to make this overlap

more formal and strategic.

vii

EQ 3: To what extent did SVC address the issue of increased gender equality and increased

women’s socio-economic empowerment in target communities?

Findings

What approaches have been most effective? SVC has nearly reached its 50 percent target for

training participants who are women and has exceeded its 30 percent target for women in leadership

positions at targeted POs, cooperatives, and businesses. The online survey, CATI survey, and stakeholder

interviews revealed that most stakeholders in all stakeholder categories agreed that SVC has had a positive

impact on gender equity and women’s socio-economic empowerment.

Eighty percent of female farmer trainers responding to the online survey said the CFC training increased

their coffee production, 55 percent said it increased their sales and income, and 70 percent said it

improved gender equity and women’s socio-economic empowerment, while most women who responded

to the CATI survey reported increased coffee production and sales as a result of the CFC. Eighty percent

of 174 GALS participants responding to the CATI survey said the training increased sharing in household

decision-making, while 95 percent said they met with community members to help them better understand

gender relationships. SVC’s internal GALS assessment, which included interviews with 389 GALS

graduates, found that 49 percent of women surveyed reported increased access to productive assets to

participate in targeted VCs, and 43 percent said the training helped them start small businesses.

Interviewees reported women having greater say over how agricultural land is used, women’s increased

leadership in household and agricultural decision-making, a decrease in spousal domestic violence, greater

transparency around income and savings, and more active participation of youth in VCs. In KIIs and FGDs,

stakeholders ranked SVC’s record on gender integration as one of its top achievements. The evaluation

also found that GALS’ approach helped create 562 new micro, small, and medium-sized enterprises

(MSMEs), including 357 new livestock enterprises (38.4 percent woman-owned) and 205 sole-owner

market activities (47.3 percent woman-owned); 54 percent of the MSMEs were created by youth.

Stakeholders attributed SVC’s strong gender performance to 1) success in retaining women for activity

staff positions; 2) strict adherence to gender and youth training targets; 3) piloting and adjusting the GALS

methodology to DRC’s post-conflict context and scaling it up through trainings of trainers (TOTs); and

4) commitment to retraining. As of June 2020, SVC had provided GALS training to 103 senior government

officials, concessionaires, and USAID-funded project staff and 353 people in six territorial-level workshops.

How can SVC more effectively integrate cross-cutting sectors and gender considerations

into interventions? Reported in stakeholder interviews, constraints to SVC integrating cross-cutting

sectors and gender into activity interventions are limited access to finance to scale up action plans, lack of

follow-up from SVC, a limited number of persons trained, and high levels of illiteracy among women. The

biggest challenges are inadequate staffing and co-support from the DFSAs, failure to mainstream GALS

trainees at the DFSAs, and inadequate tracking of TOT and cascading training to other PO members and

CFC groups. Frequent recommendations from SVC and DFSA staff were additional training and incentives

for GALS champions, scaling up GALS training for POs, and increasing PO support for integrating youth

into existing POs.

Conclusions

There is evidence that the SVC GALS model 1) is an effective approach for empowering women; 2) is well

adapted to post-conflict transition economies; and 3) provides a scalable mechanism, through GALS

champions, for monitoring training and providing follow-up.

SVC’s ability to fully scale up and pilot test the GALS model has been hampered by a shortage in GYSI

staff, a lack of territorial-based field officers, and weak coordination with the DFSAs (see EQ 2).

Sustaining GALS achievements is not guaranteed since it will require a concerted effort to link GALS

champions and trainees to women members and leadership of POs and cooperatives.

viii

EQ I C: What are some of the challenges faced in meeting the intended goals, objectives,

and results? How effectively has the implementer dealt with those challenges? What can be

changed to better meet goals and objectives?

EQ 4: What are the internal and external threats to sustainability beyond the life of the

activity for the principal components of the SVC?

Findings

Primary Challenges and Threats to Coffee and Agriculture/Agribusiness Sectors: Only

58.1 percent of online respondents felt the conditions for ensuring sustainability of SVC’s results were

fully assured, due to several external and internal challenges. The online survey rated low prices and low

sales for farm products, access to finance, access to agricultural inputs, access to market information, lack

of price differentiation, limited opportunities to form commercial linkages, and lack of private investment

in agriculture as the greatest challenges in the coffee sector and access to finance, government policies

that inhibit markets, and opportunities to form commercial linkages as the greatest challenges in the

agricultural and agribusiness sectors. Coffee and dried bean farmers in the CATI survey rated lack of

access to finance and to tools and equipment as the biggest challenges.

Predictable and Unpredictable Challenges and Threats: The predictable external threat to

sustainability most frequently cited in stakeholder interviews was the humanitarian mindset of community-

based stakeholders and local governments more focused on meeting the immediate needs of vulnerable

farmer households than developing and expanding markets. Other predictable external threats frequently

mentioned are the different philosophical approaches taken by SVC and DFSAs, logistical challenges, and

conflict and insecurity. The most frequently cited unpredictable threats were natural causes (COVID-19,

Ebola, and climate change) and shifts in donor policies, i.e., trafficking in persons (TIP) sanctions.

Component 1: Build Capacity of Vertical and Horizontal Actors in Targeted VCs: The biggest

challenges and threats to sustainability in Component 1 are lack of access to quality agricultural inputs,

including tools and equipment for bean production; lack of access and willingness to buy quality seed;

government policies inhibiting markets; limited adoption of post-harvest practices; limited opportunities

to store or warehouse crops; weak organizational capacity of dried bean and soybean POs; limited

opportunities to form commercial linkages; lack of market linkages and markets to sell products; limited

private sector investment by concessionaires and private enterprises; lack of access to land use; limited

adoption of improved production practices; low productivity; and high production costs.

Component 2: Enhance Coffee Production: Principal challenges to sustainability of Component 2

are the weak capacity of POs, cooperatives, and RCPCA to facilitate services SVC provides community-

based coffee groups; limited adoption of recommended coffee practices to produce high-quality coffee;

lack of tools, equipment, and agricultural inputs; limited access to market information and opportunities

to form commercial linkages; monopolistic practices of cooperatives that manage washing stations; limited

access to finance for more washing stations; weak cupping capacity of washing stations; dependence of the

coffee sector on international roasters; and fluctuating prices.

Component 3: Develop and Implement PPPs: Component 3 sustainability challenges include

facilitating dialogue between private sector enterprises in targeted VCs and government; low capacity of

private sector organizations to engage in PPP dialogue with government officials; low government

responsiveness and involvement; lack of awareness and understanding of the PPP concept and approach;

lack of private investment in agriculture; and lack of SVC staff in Kinshasa to support policy initiatives and

develop the PPPs stakeholders have identified as best practices.

Component 4: Access to Finance: Key challenges to the sustainability of Component 4 activities are

the risk that FIs that benefited from DCA-guaranteed loans will not continue supporting larger VC

agribusinesses; USAID-funded loan guarantees mitigate but do not resolve the impact of external and

ix

internal constraints; the lack of financial offerings that are adopted to rural-based POs and cooperatives;

and the weak financial literacy of cooperatives and POs.

CCIR: Gender, Youth, and Social Inclusion: The most pressing challenges to CCIR activity

sustainability are the need to intensify gender training and messaging, insufficient field staff and monitoring

and oversight of activities, low literacy levels among women, integration of gender messaging into VC

training and assistance activities, and limited youth engagement.

Staff and Partner Capacity: Examples of how SVC is succeeding in building the capacity of the activity

staff and local partners include capacity building on quality coffee production; improved post-harvest

practices; improved coffee farming practice; increased agriculture and agribusiness loans; training in

entrepreneurial management, strategic planning, and financial management; exchange visits with non-SVC

institutions and programs; and training on improved advocacy at different levels of government. Gaps in

sustainable capacity development include the lack of follow-up and mentorship on GALS training; an

inadequate training plan for community trainers; lack of central database to track capacity building; lack of

a tracking system for SVC TA; and weak capacity of SVC to track cross-cutting capacity building envisioned

in the shared results framework.

Conclusions

Stakeholders and SVC staff identified a number of external and internal challenges and threats and cross-

cutting and component-specific challenges and threats for SVC to address.

Two cross-cutting challenges are outside the SVC mandate: the limited productivity and production

support for the dried bean VC and limited access to finance for the larger infrastructure investments that

SVC needs to support the scale up of the specialty coffee and dried bean VCs.

While SVC can make significant progress to address component-specific challenges and threats and

strengthen its connections to the DFSAs to increase crop productivity, it is unlikely all of the conditions

needed to sustain many activities will be in place by SVC’s end date.

EQ 5: What considerations should USAID/DRC consider in the future design of

agriculture/economic growth (EG) activities, particularly in regard to the IRs in the shared

results framework and ways to improve collaboration/coordination between USG activities?

Findings

Below are 11 considerations for future USAID/DRC agriculture/EG programming, presented by IR.

IR 1: Improved Agricultural Livelihoods

1. Support full VCs (not half VCs).

2. Strengthen farmers’ access to quality inputs.

3. Encourage VC diversification and support.

4. Promote inclusive agri-business models.

IR 2: Expanded Markets and Trade

5. Promote TOT training to build POs’ capacity for post-harvest processing, warehouse management, and

market linkages for dried beans.

6. Anticipate the need for specialized investments to ensure the quality standards needed to access the

international specialty coffee market.

7. Facilitate increased access to finance.

8. Support an improved enabling environment for VC activities.

IR 3: Improved Uptake of Essential Nutrition Behaviors and Services

9. Promote increased awareness of and access to nutritious food.

x

CCIR: Gender Equality and Social Empowerment (SBCC and Conflict Mitigation)

10. Strengthen future programs’ support for gender equality and empowerment in South Kivu.

Improved Collaboration with Other USAID-Funded Projects

11. Improve intra-USAID coordination.

Conclusions

Senior stakeholders agree on the validity of the ongoing CDCS TO 3 strategy to help South Kivu transition

out of dependency on humanitarian aid and that the envisioned layering and sequencing of support by

USAID projects is the best mechanism to achieve the results outlined in the 2013 Kivu Agriculture and

Nutrition Shared Results Framework.

Poor roads, underfunded local governments, competing militias causing civil unrest, and poor government

agricultural policy remain in South Kivu, but this evaluation confirmed that 1) despite long odds, a growing

number of FFP and non-FFP SVC beneficiaries are taking steps toward the market, and 2) DFSA and SVC

activities helped facilitate this process.

The ET identified nine summary considerations to guide USAID/DRC’s future programming in South Kivu

and nine examples of best practices to consider in future program design in the region.

RECOMMENDATIONS

Recommendation 1: Staffing and Management: Strengthen SVC’s ability to backstop targeted VCs.

Recommendation 2: Capacity Building: Strengthen SVC’s capacity to build technical and cross-

cutting capacities of stakeholder groups.

Recommendation 3: Inputs: Increase the direct beneficiaries of SVC and DFSAs and strengthen their

understanding of and access to the quality inputs to scale up and sustain VC activities.

Recommendation 4: Finance: Strengthen stakeholders’ access to finance for working capital and

investments and critical equipment and infrastructure.

Recommendation 5: Market Diversification (Specialty Coffee): Continue to scale up SVC’s efforts

to collaborate with RCPCA in promoting market diversification and quality control.

Recommendation 6: Enabling Environment: Continue to support and scale up SVC’s support for

promising Government of the Democratic Republic of the Congo-led initiatives to improve the enabling

environment.

Recommendation 7: Coordination: Strengthen SVC’s internal capacity to support improved

coordination with the DFSAs.

Recommendation 8: Gender, Youth, and Social Integration: Continue to scale up SVC’s support

for youth and gender entrepreneurship in collaboration with the DFSAs.

Recommendation 9: Annotated Bibliography/Case Studies of SVC Best Practice: Facilitate

development of an annotated bibliography of existing data and technical reports on SVC best practices.

1

1.0 EVALUATION OVERVIEW

1.1 EVALUATION PURPOSE AND AUDIENCE

The purpose of the Strengthening Value Chains Activity (SVC) mid-term performance evaluation is to

provide an independent examination of the activity’s progress and accomplishments. The evaluation

assessed the achievements, performance, and constraints related to activity implementation and

effectiveness, with a focus on the effectiveness of the collaboration with Food For Peace (FFP) in the same

geographical areas of focus. From this, the evaluation has identified results and lessons learned and a set

of actionable recommendations to ensure the achievement of activity objectives for three time horizons:

short-term (one to two years), medium-term (three to four years), and long-term (greater than five years).

The primary evaluation audience is the United States Agency for International Development/Democratic

Republic of the Congo (USAID/DRC), the Bureau for Resilience and Food Security (RFS), and activity

implementing partners (IPs). The evaluation will also be used by the Government of the Democratic

Republic of the Congo (GDRC), and FFP and other donor-funded projects in the DRC.

1.2 EVALUATION QUESTIONS

The evaluation focused on answering the five primary evaluation questions (EQs) found below. (See

Annex 1 for the full list of EQs and sub-EQs.)

1. To what extent is SVC meeting overall intended goals and objectives?

2. In what ways is SVC’s collaboration with other United States Government (USG) activities

effectively contributing to the Sub-Intermediate Results (Sub-IRs) in the shared results frameworks

and the shared contract target?

3. To what extent did SVC address the issue of increased gender equality and increased women’s

socio-economic empowerment in target communities?

4. What are the internal and external threats to sustainability beyond the life of the activity for the

components of SVC? What are the biggest challenges that need to be addressed? What

opportunities are there for the Mission to better ensure sustainability?

5. What considerations should USAID/DRC consider in the future design of agriculture/Economic

Growth (EG) activities, particularly in regard to the Intermediate Results (IRs) of the shared

results framework?

2.0 ACTIVITY BACKGROUND

2.1 MECHANISM DESCRIPTION

2.1.1 Context

In 2013, the USAID/DRC Country Development Cooperative Strategy (CDCS) committed USAID to

support a new model of integrated regional transition planning for Eastern Congo designed to shift

assistance focus away from humanitarian relief toward a market-led development as articulated in CDCS

Transition Objective (TO) 3. To achieve TO 3, USAID developed a regional strategy in which USAID-

funded activities in South Kivu would collaborate with one another to achieve the three principle

objectives of the Kivu Agriculture and Nutrition Shared Results Framework (Figure 1).

SVC was originally conceptualized as one of three categories of USAID-funded activities to achieve the

Kivu Agricultural and Nutrition Shared Objective, “Reduce extreme poverty and malnutrition in target

populations.” The two other categories of programming included the two FFP projects known as

2

Development Food Security Activities (DFSAs) and other USAID-funded projects

1

that were active in the

area. SVC’s stated purpose is to “increase household incomes and access to nutrient-rich crops by linking

smallholder farmers to strengthened and inclusive value chains and supportive market chain services.”

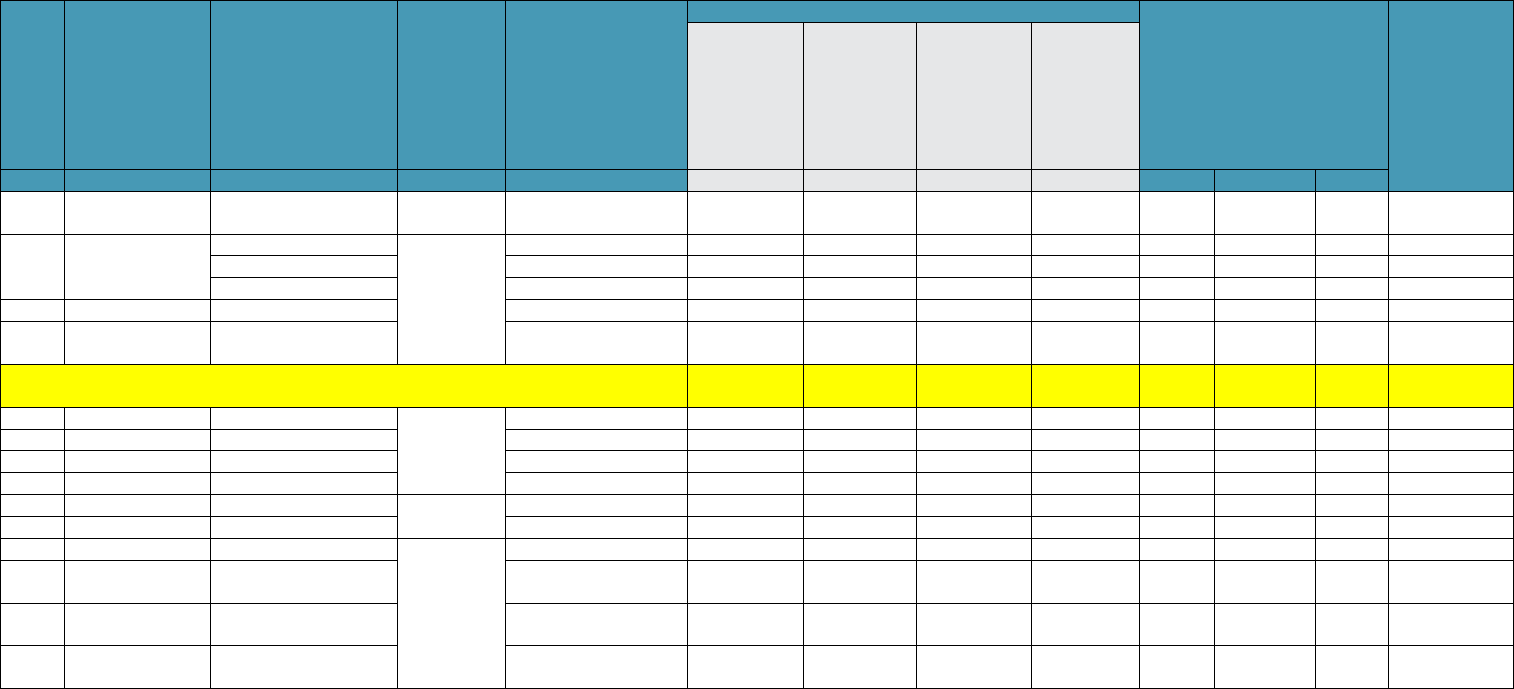

Figure 1: Kivu Agriculture and Nutrition Shared Results Framework (2013)

Source: USAID/DRC. (2013). CDCS (Fiscal Year [FY] 2014-FY 2019), Kinshasa: USAID.

2.1.2 Target Populations and Areas

SVC seeks to contribute to USAID/DRC’s goal of a significant reduction in extreme poverty and

malnutrition in the Eastern Congo areas being targeted by the CDC TO 3 through building the capacity

of the vertical and horizontal actors working within the coffee, dried bean, and soybean value chains (VCs)

in the South Kivu territories of Kabare, Kalehe, and Walungu. Tetra Tech implements SVC in collaboration

with five IPs: Banyan Global, J.E. Austin Associates, Inc., Search for Common Ground (SFCG),

TechnoServe, and World Coffee Research (WCR). Contractually, SVC’s assistance to the dried bean and

soybean VCs is limited to post-harvest to market activities, while its assistance to the coffee VC covers

the entire VC.

1

Other USAID-funded programs include the Integrated Youth Development Activity (IYDA), Integrated Health Project (IHP),

Integrated Governance Activity (IGA), and the USAID-funded Development Credit Authority (DCA).

3

In Fiscal Year (FY) 2020, the activity started supporting light touch operations in the territory of Idjwi.

The three territories vary significantly in terms of the degree to which the crops targeted by SVC are

cultivated as well as other context issues (e.g., prevalence of mining, degree of donor dependence, and

level of insecurity and cross-border trade) that are likely to affect both the rollout and results of the SVC

interventions.

SVC is organized around five components: 1) build capacity of vertical and horizontal actors in targeted

VCs (Tetra Tech); 2) enhance coffee production (Technoserve and WCR); 3) develop and implement

public-private partnerships (PPPs) (J.E. Austin); 4) enhance access to finance (Banyan Global); 5) cross-

cutting initiatives, including 5a) gender, youth, and social inclusion (GYSI) (Banyan Global) and 5b) conflict

mitigation, resilience, and social and behavior change communication (SBCC) (SFCG). Components 3-4

are cross-cutting components and Components 5-6 are cross-cutting priorities. The component teams

were expected to work with the DFSAs and other USAID and non-USAID projects to benefit diverse

actors, including the provincial, territorial, and local governments, producer organizations (POs),

cooperatives, agro-dealers, concessionaires (large landholders), collection centers, warehouses, wet mills,

buyers, financial institutions (FIs), and smallholder farmers not attached to POs or cooperatives. By June

2020, SVC was working with 45,291 direct beneficiaries, 50 percent more than its contractual target of

30,000, and 61,000-92,000 indirect beneficiaries.

The actors that need capacity building are the national and local GDRC officials, POs, cooperatives, agro-

dealers, concessionaires, collection centers, warehouses, wet mills, buyers, FIs, and smallholder farmers.

Given the critical role of women in farming, trade, and the construction and maintenance of a more

durable peace, the issue of building women’s leadership capacity was a critical cross-cutting priority in all

of the capacity building activities.

2.1.3 Activity Implementation Plan

SVC interventions vary by VC and territory (see Figure 2). In the coffee VC, SVC has contractual

responsibility to develop the entire coffee VC in Kabare and Kalehe, and now in Idjwi, including working

to improve the management of small-scale coffee farms.

2

In the dried bean and soybean VCs, SVC is

strengthening horizontal and vertical linkages from post-harvest to market, while the FFP-funded DFSAs

are improving dried bean and soybean production and productivity in Kabare and Kalehe territories.

T

he two FFP-funded DFSAs vary in the type of support they provide. The Food Security Project (FSP)

DFSA, implemented by Mercy Corps (MC) in Kabare and its sub-contractor World Vision (WV) in South

Kalehe, works to strengthen production of bio-fortified beans but does not work in the soybean or non-

fortified dried bean VCs. The TUENDELEE PAMOJA Project DFSA, implemented by Food for the Hungry

(FH) in Walungu, targets the fortified bean and soybean VCs on the production side with a special focus

on supporting applied research on productive varieties.

SVC’s geographical areas overlap with the two DFSAs and with seven economic poles, defined as rural

aggregator markets SVC identified as dynamic with maximal capacity to benefit from its interventions and

services in its FY 2019 annual work plan.

2

The initial TechnoServe assessment indicated that the coffee VC was more developed in Kabare and Kalehe and by focusing

there, the target of 15,000 households could be reached. Idjwi was originally considered for inclusion but was removed by the

GRDC for political reasons. Requests for interventions resulted in Idjwi being reintegrated into SVC’s activities in FY 2020.

4

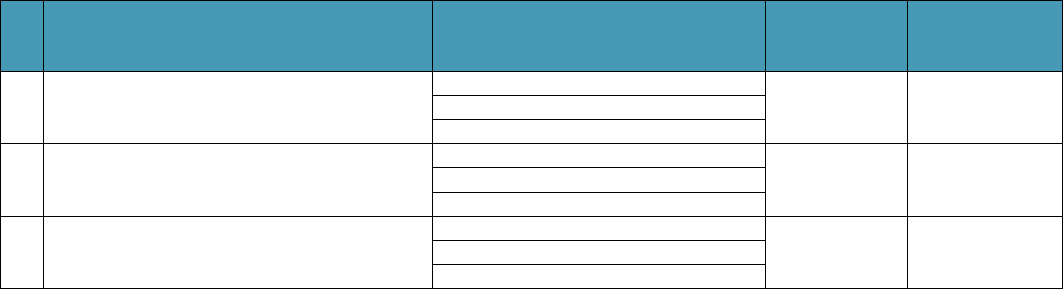

Figure 2: FTF SVC and FSP Locations

5

Figure 3: Co-Location Areas Between FSP and SVC Activities

3.0 EVALUATION METHODS AND

LIMITATIONS

The evaluation team (ET) adopted a mixed-methods approach to answer the EQs consisting of key

informant interviews (KIIs), focus group discussions (FGDs), online surveys, a computer-assisted

telephone interview (CATI) survey, and mini-surveys. Since these methods covered similar questions, this

enabled the ET to triangulate the evaluation findings from multiple qualitative and quantitative data sources.

6

3.1 DATA COLLECTION METHODS

Document Review: The ET received a list of documents from SVC and then worked closely with SVC

to update the list. A complete list of documents reviewed can be in Annex 13.

KIIs/FGDs: The revised evaluation plan included eight KII and FGD guides for seven categories of

stakeholders in the DRC, Europe, and the United States. Given the importance of protecting the health

of the national consultants and stakeholders being interviewed, the plan anticipated how the KII and FGD

methodology could be adjusted to three different coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) scenarios.

The ET used a two-step process to select interviewees, starting by co-developing a database with SVC

ranking each stakeholder group by level of engagement. From this database, the ET selected interviewees

based on their level of engagement and its informed judgment about who would be able to answer the

EQs. While this selection was not random, the ET considered this purposive sample reasonably

representative since these are the chief persons familiar with SVC within their organizations. This color-

coded database provided the basis for the ET to choose a reasoned sample of groups to interview that

included 1) a representative sample of groups from different stakeholder categories in each region and

2) the ET’s actual or physical access to the group based on security bans and/or COVID-19 concerns.

Overall, the ET interviewed 292 people in Bukavu, Kinshasa, Europe, and the United States, including 33 in

KIIs and 259 in FGDs ranging from 2-13 people, with most between 2-4 persons due to the COVID safety

guidelines (see Annex 12). KII and FGD notes were analyzed using Atlas.ti to produce a frequency analysis

of key themes. Because of GDRC bans on travel outside of Bukavu, only 23 (29 percent) of the

96 interviews were in person, the remaining were done by telephone, Skype, Google Meet, or Zoom.

CATI Survey: SVC’s beneficiary smallholder farmers number in the thousands, thus only a fraction of

them can be accessed using KIIs and FGDs. To address this issue, ME&A’s subcontractor GeoPoll

conducted a CATI survey of beneficiary smallholder farmers. The survey sampling frame was the full list

of 2,589 smallholder farmers who participated in the field trainings and 417 who participated in the Gender

Action Learning System (GALS) workshop. GeoPoll randomly selected and surveyed 1,003 persons from

this call list consisting of 800 coffee, dried bean, and soybean farmers and 203 GALS participants.

Online Survey: The ET created versions of the online survey for six stakeholder groups not included in

the CATI survey including a set of standardized and customized Yes/No, categorical, Likert-scale, and

open-ended questions. To increase the survey response rate and control the problem of invalid email

addresses, the ET distributed an initial emailed letter of invitation to each targeted stakeholder. The English

letter of invitation for stakeholder categories I, III, and IV was co-signed by the SVC Contracting Officer’s

Representatives (CORs) and the USAID/DRC FFP manager; the French cover letter of invitation was from

the SVC Chief of Party (COP), since he was the person that stakeholders would know. A total of

277 stakeholders with listed Internet addresses were sent invitations to take the survey; 251 (91 percent)

accepted the invitation, and 183 (73 percent) of those who confirmed the invitation completed the survey.

Mini Surveys: The KII and FGD guides incorporated mini-surveys consisting of Yes/Know or Likert-scale

questions targeted to different stakeholder groups on topics such as capacity building, on-farm production,

SBCC, and gender/GALS.

Performance Indicator Tracking Table (PITT): To assist the ET in understanding SVC’s

performance, Tetra Tech developed a consolidated PITT which can be found in Annex 6.

3.2 METHODOLOGICAL LIMITATIONS

One methodological limitation was that the two international consultants were unable to conduct field

visits due to COVID-19. The ET mitigated this limitation by forming a team with extensive experience in

francophone Africa and Feed the Future (FTF) evaluations and in online teaching and interviewing. It also

worked closely with its local subcontractor Research Initiative for Social Development (RISD) to conduct

an initial ten-day refinement and field testing of the KII and FGD guides and intake forms. A second

7

limitation was the COVID-19 pandemic. To manage this limitation, the evaluation plan anticipated the

need to support the research under three security scenarios. Developing these scenarios ahead of time

proved useful once GDRC decrees on June 13 necessitated remote interviews. Related to this, the remote

data collection limited the kinds of interpersonal interactions that make face-to-face interviewing and

group discussions more dynamic, such as the ability to read and react to body language and facial cues and