Labels, Artists, and Contracts in Today's

Music Industry: An Economic Analysis

By Debra J. Aron, Ph.D.

*

and Steven S. Wildman, Ph.D.

**

August 1, 2023

*

Vice President, Charles River Associates, [email protected]

**

Professor & J.H. Quello Chair of Telecommunication Studies Emeritus, Michigan State University,

swildman@msu.edu

This research was funded in part by the RIAA. The views expressed herein are the views and opinions of the

authors and do not reflect or represent the views of the RIAA, Charles River Associates, or any of the organizations

with which the authors are affiliated.

Copyright 2023 Charles River Associates

Table of Contents

Executive Summary ........................................................................................................................ 1

I. An Overview of the Relationships Between Labels and Artists in the Music Industry .......... 6

A. Introduction .......................................................................................................................... 6

B. Services and Resources Available to Recording Artists in Today’s Music Industry .......... 7

II. The Music Industry Has Changed Dramatically in the Last 20 Years .................................. 10

A. The technological drivers of music industry change ......................................................... 11

B. The distribution and consumption of music have changed ................................................ 14

C. Opportunities for artists and independent labels ................................................................ 18

D. Adjustments by major labels .............................................................................................. 30

III. Contractual Arrangements with Artists ................................................................................. 31

A. The relationship between artists and labels is complex ..................................................... 31

B. The structure of artists’ contractual arrangements addresses these complexities .............. 37

IV. Conclusions ........................................................................................................................... 47

1

Executive Summary

The music recording industry has undergone dramatic change in the last twenty years. The ways

that music is marketed, distributed, and even produced are almost unrecognizable compared to the

way things were done at the turn of this century. This study updates and expands a study of music

industry contracts performed by one of the present authors in 2002. Since that time, the

development of digital technology, the broad dissemination of broadband access, and the near

ubiquity of smartphones, laptops and tablet devices have revolutionized the distribution of music.

Instead of visiting brick-and-mortar retail establishments selling music on physical media,

consumers today largely obtain and consume their music via streaming and downloads from the

comfort of their homes, during their commutes, at work, at the gym, or at leisure. Music can be

obtained by subscription, providing consumers the ability to access a massive variety of content at

no incremental (per-song or per-album) cost–a pricing structure that, compared to having to pay

by the individual album or single, encourages more experimentation in sampling new music.

Vendors who once sold music in physical stores and had to curate a limited selection of options to

meet the realities of limited physical shelf space have been largely replaced by online streaming

services who face no similar physical limitations to the number of options that can be offered to

consumers. Brick-and-mortar vendors with the ability to steer consumers to certain titles, genres,

or artists by their choice of inventory have been replaced by influencers, both independent and

commercial, who create playlists that, by identifying trends and highlighting promising artists and

releases, help streaming customers make selections from nearly boundless collections of

recordings and, on occasion, launch previously obscure artists on a path to stardom.

The impact of the digital revolution on the music industry is readily apparent in industry statistics.

Today 83 percent of total music revenue is accounted for by streaming services, a delivery mode

that did not exist twenty years ago. Moreover, despite the far greater range of music available to

consumers today, the total revenue generated by the sale of that music, whether via physical media

or digital media, is far lower than it was twenty years ago. Consumers are getting a lot more and

paying a lot less.

The digital revolution in music has not only democratized the selection of music available to

consumers by placing the choice among a vast array of options in their own hands (literally, at

2

their own fingertips), but by making it possible for virtually anyone to upload a recording to a

streaming service or digital download vendor at very low cost, the digital revolution has also

expanded the range and quantity of music created. Consumers searching today’s digital music

services may find recordings by obscure artists and tunes produced and recorded in bedrooms and

garages alongside the work of the world’s most famous pop stars. Music today can be produced

in an artist’s bedroom at a level of fidelity that was once achievable only in professional studios.

The major music labels traditionally identified and signed a roster of artists to whom they offered

an extensive suite of services–including business expertise; advance funding; matchmaking with

producers, studio musicians, and other creative professionals; marketing; and distribution of music

that artists needed to be commercially successful, in exchange for a share of the revenues generated

over multiple projects. Today, artists have far more ways to obtain those services, ranging from a

menu of à la carte options provided by numerous companies serving artists seeking to assemble

their own package of services without contracting with a label, to working with independent labels

that also can provide a comparable suite of services, to contracting for particular services “à la

carte” from the major record companies’ label services divisions. While the major labels have

scale and resources for supporting artists unmatched by independents and DIY options, it is not

necessary for an artist to be signed to a major label today to access the marketplace or the

technology and services needed to produce and sell their music and enjoy considerable success

doing so.

Independent labels and artists working independent of labels (the so-called do-it-yourself or DIY

artists) have benefitted from these changes. Independent labels have been able to build new

businesses providing artists with distribution to and assistance with promotion on streaming

services and via social media, and because the streaming services and digital download vendors’

music catalogues are searchable using tools these services provide, music consumers are able to

find and listen to music from artists signed to independent labels whose releases would not have

been stocked by record stores in the past. A notable number of DIY artists have been able to

achieve prominence and mainstream success by building audiences on streaming platforms with

the help of services acquired on an à la carte basis from independent vendors or, in some cases, by

literally managing promotion and arranging distribution to online services on their own.

3

Labels are in the business of finding and nurturing promising talent and helping established artists

realize their full commercial potential. For artists who are offered and choose to accept contracts

with labels, there are certain realities of the music business that must be addressed. These include

a label’s role in nurturing new talent; the need to help some artists, and new ones especially, fund

the production, marketing, and distribution of their music; the benefits of guidance and advice that

can help artists realize their artistic visions; the value of business knowledge; business connections

that can match artists with individuals with complementary talents; the benefits of back-office

assistance for reaching an audience; the unpredictability of commercial success for new artists

especially, but also for forthcoming releases from established artists; and the unavoidably delicate

relationship between an artist and a label that encompasses so many judgements and decisions that

cannot be perfectly anticipated in a contract. While labels’ efforts on behalf of their artists cannot

eliminate the risks attendant to the creation, promotion, and sale of recorded music, they can

increase the odds that artists’ efforts will be met with success and, by sharing the risks, mitigate

for artists the downside of failed releases. These realities largely motivate and determine the way

that artists and labels contract with one another.

The substance and variety of label contracts today are a reflection of the modern music industry.

As in the past, major labels provide a set of services to artists with whom they have contracts, the

elements of which may vary, plus an advance of funds to support the artist and the production of

the artist’s work. Label-supplied services typically include distribution, marketing and promotion,

among other things. Major label contracts typically provide terms for an initial recording project

(such as an album) and terms for a specified number of additional projects. The terms for the

additional projects are often conditional on the success of previous albums and allow for increased

advances and royalties the greater the artist’s success. The contracts allow the artist and the label

to share both the risks and potential rewards of recording projects by limiting the artist’s downside

risk—the advance may never be recovered by the label if the album does not produce enough

revenue—while allowing the artist and label to share in the upside potential of the work if it is

commercially successful.

Based on our review of contract data and other information from the major record labels, we can

report that for different artists the amounts of advances and royalty rates may vary by an order of

magnitude or more. The number of projects optioned, and the mix and types of recordings covered

4

by contracts, also vary considerably. It is clear that contracts are highly individualized and

bespoke, as would be expected since they are tailored to needs and desires of an artist and those

vary widely among individual artists. Variation among contracts shows that just about all terms

are subject to negotiation, and indicates further that contract terms are heavily negotiated. The

data also show that artists are virtually always represented by legal counsel in their negotiations,

and that labels give artists advances to cover the cost of legal representation in their contract

negotiations.

One notable feature of label recording contracts that has remained consistent over the last twenty

years (at least) is that they are project-delimited rather than time-delimited. That is, a contract

provides for a specified number of projects rather than a set period of time, and the contract ends

when either the projects are completed or the label chooses not to exercise its option under the

contract to fund the next project. That label recording contracts are project-delimited rather than

expiring after a set period of time reflects the fact that investments and advances provided by labels

are recoverable only if the contracted projects are completed, yet the timing and pace of project

completion – even when agreed to in the contract – is in the control of the artist. In addition, while

labels’ investments in artists are project-specific, they also have a significant long-term

component. The shorter the time and fewer the projects over which a label might be able to recoup

its investment, the less a rational investor would be willing to invest, to the detriment of both the

label and the artist.

Of course, because it is always uncertain how successful an artist’s future projects will be, the

terms of a contract will reflect the information available at the time the contract is made and the

expectations of the parties at that time. Sometimes the predictions will be too optimistic, and the

label may take a loss on the contract. Other times the artist may far exceed expectations.

Successful artists may seek to renegotiate the terms of their contract before all projects have been

completed and, despite having committed to an agreement, the artist can in practice – and typically

does - exercise negotiating power and request a renegotiation of their contract before beginning

their next contracted project. Successful artists have negotiating leverage both because the artist

controls the pace of the recording process and because the label has an incentive to maintain a

good relationship with the artist and a reputation for fairness within the industry in order to re-sign

5

the artist when their contract is completed and to continue to attract and sign highly promising

artists.

The contracting documents and information we reviewed are consistent with this analysis of the

economic character of recording contracts. Although major label contracts typically specify a set

number of projects, the contractual relationship with an artist rarely remains unaltered during the

course of a contract. Moreover, artists can and do renegotiate contract terms even during the

pendency of an existing contract. Based on our review of the rosters of the three major labels over

time, we found that over half of the artists signed in 2015 (the most recent year for which we could

track artists for seven years) were no longer with their original label within four years and 69

percent were no longer with the label by year seven. In documents covering a full year for one of

the major labels, we found that of those who remained by year seven, all had renegotiated their

contract terms by that time.

Based on the broad array evidence we reviewed to produce this report, it would be hard not to

conclude that the terms of artist-label contracts and the negotiations that produce those terms are

appropriate responses to the economic challenges posed to both artists and labels by today’s music

market.

6

I. An Overview of the Relationships Between Labels and Artists in the Music Industry

A. Introduction

The music industry is complex and the relationships among the players are multifaceted. In 2002,

one of the present authors published a report describing the music industry and recording contracts

in the mid-to-late 1990s and year 2000.

1

Since that time, the industry has changed so rapidly and

extensively that understandings based on familiarity with the industry even in its recent past may

be badly outdated.

This report updates and expands the report written twenty years ago to reflect the sea-change in

the music industry driven by advances in technologies and new services designed to take advantage

of the new capabilities unleashed by those technologies. We describe certain key features of the

structure of the music industry today and critical players in the industry, along with a discussion

of music industry economics.

We pay particular attention to the economic characteristics of contracts between artists and labels

and the non-label options available to artists to assist them with creating, recording, marketing,

and selling their music. The market participation and market power, if any, of streaming services

and their pricing and intellectual property practices vis à vis artists are important topics in the

modern music industry and ones that have garnered much press recently, but are outside the scope

of this report. We focus on the role of the labels in the modern industry and the economic functions

of their contract structures and practices. Our view is that public policy regarding recording

contracts must be informed by an understanding of the goals, challenges, incentives, and benefits

that contracts between artists and labels encompass. Our hope is that policymakers will be able to

draw on the information and perspectives presented in this report to make better-informed choices

when crafting the laws and policies that will govern the music industry going forward.

The remainder of this report is organized as follows. In the next subsection, we provide an

overview of the many services that complement and support the endeavors of music artists today,

and the institutions that have emerged in the marketplace that operate alongside and as alternatives

1

Steven Wildman, “An Economic Analysis of Recording Contracts,” July 22, 2002 (hereafter, 2002 Wildman

Report).

7

to the major labels to provide these services and enable artists to realize their vision and advance

their ability to bring their music to commercial fruition and financial success.

Section II provides a brief overview of the technological changes and new services and institutions

based on those changes that have upended the way fans explore, purchase, and consume music and

the way artists produce and market their music and connect with their fans. We explain and

provide examples of the many options available to artists today from high-touch independent and

major labels to à la carte and off-the-shelf services, and we discuss how the major record

companies have responded to the industry changes as well.

In Section III, we describe the challenges and nuances of the relationship between artists and labels

and the role of the major terms of artist-label contracts in sharing risk and reward and aligning the

incentives of both parties toward the common goal of commercial success for the artist, in part by

allowing contract terms to vary substantially to appropriately reflect differences in artists’

circumstances and needs. We explain that certain fundamentals of the artist-label relationship

remain unchanged—and therefore, certain fundamental features of recording contracts that served

a recognizable purpose in promoting successful artist-label relationships 20 years ago appear in

modern contracts as well—but the profound changes in the industry have been accompanied by a

notable amplification in the variety of contractable services available to artists. Section IV

contains concluding comments.

B. Services and Resources Available to Recording Artists in Today’s Music

Industry

Musical recordings, as with many other types of media content such as films, TV programs, novels,

news reporting, and blogs, for which demand is driven by content, differ from most other consumer

goods in economically important ways. Each recording is a unique expression of the vision and

intent of an individual artist; once the initial (master) recording is created, the costs of replication

are extremely low and the cost of distributing another unit of an individual recording through any

of the various channels tends to be low as well (for digital distribution it is close to zero), even

though the costs of maintaining and operating the distribution channels may be quite high.

Whether an audience of economically meaningful size for the artistic expression embodied in any

specific recording exists cannot be known in advance, and in a music market where 100,000 new

8

tracks (songs) are uploaded to streaming services every day

2

and many millions of earlier

recordings also compete for listeners’ time and attention, there is no guarantee that the listeners

who may like a recording can be found even if they do exist. Recordings in which artists and

labels have invested considerable time, effort, and money in anticipation of strong sales may fail

to cover their costs. Time and financial commitments to the creation of new music are therefore

inherently risky.

These factors make the market for recorded music difficult to navigate and challenging for artists

and the companies that invest in and promote their careers. The challenges are especially great for

new artists at the beginnings of their careers when they still have much to learn about the music

business, including frequently the process of creating and recording music with commercial

appeal. It is possible today for an artist to record a song with high fidelity sound using home

recording equipment

3

and upload it to one of the streaming services like Spotify, Pandora, Apple

Music, or YouTube, thereby making it available to a worldwide audience. For artists who enjoy

sustained commercial success there is almost always much more involved, beginning with the

production of a recording for which an artist has turned to a professional producer with a recording

studio for help finding and refining a sound that matches their artistic vision, and often for

managing the recording processes itself. Labels can help to facilitate matching between a record

producer and an artist, or help finance the purchase of a particular instrument,

4

identify songs for

the artist to record, pay for professional studio time, or help secure the use of excellent studio

musicians, among other components of a music recording–services that can be especially valuable

to new artists still finding their way in the industry. Our review of contract data provided by the

major recording companies showed that contracts for artists signed to the major record companies’

labels typically include label-funded budgets for recording costs. That labels are willing to commit

upfront to cover the cost of working with a producer is strong evidence that the labels believe that

2

Tim Ingham, “It’s Happened: 100,000 New Tracks are Now Being Uploaded to Streaming Services Like

Spotify Each Day,” Music Business Worldwide, October 6, 2022,

https://www.musicbusinessworldwide.com/its-happened-100000-tracks-are-now-being-uploaded/.

3

For example, Billie Eilish famously recorded her first album in her bedroom, produced by her brother Finneas.

Alice Gustafson, “Billie Eilish’s Happier Than Ever: Bedroom Production Reaches New Heights,” Headliner,

accessed February 8, 2023, https://headlinermagazine.net/billie-eilish-happier-than-ever-bedroom-production-

reaches-new-heights.html.

4

“Everything You Need to Know About Record Labels,” The Planetary Group, accessed February 1, 2023,

https://www.planetarygroup.com/music-promotion-guide/record-labels/.

9

working with a good producer can increase substantially the appeal and the likelihood that the

artist’s recordings will achieve financial success, including a fair return on the label’s investment

in the artist.

Producing a recording is only the beginning of the process of finding an audience willing to pay,

or listen to ads, for the right to stream an artist’s work. Once an artist’s music has been recorded

it must be placed with appropriate distribution channels, where in-channel promotion can be

critical to finding an audience. Advertisements for a particular artist’s work may be placed within

the various streaming services

5

and securing inclusion in the right curated playlists on those

services can also be important to creating and managing an artist’s profile.

6

There may also be

advertising in other media, both online and offline, as well as efforts to promote an artist’s work

by bringing it to the attention of critical gatekeepers and influencers, such as people who construct

radio playlists, book TV appearances, write reviews of recent releases, and publish influential

playlists for streaming services. If physical as well as digital copies of a recording are to be sold,

their manufacture must be arranged and their placement in distribution channels for CDs and vinyl

records secured. Promotion outside of the streaming platforms is also often arranged and if an

artist tours in support of a recording, labels will potentially assist with coordinating venues and

tour dates along with lodging and travel.

Few if any artists have the expertise to handle all of these noncreative activities well, and even if

they did, the time required to manage them would come at the expense of time that could have

been spent developing, recording, and performing their music. In addition, because many of these

activities are costly, limited financial resources can also make it more difficult for new artists,

especially, to break out.

As would be expected, a variety of institutions, organizations, and services have been developed

to help artists create their music and find and connect with listeners who may enjoy their songs.

5

See, for example, “Turn up Your Music Marketing,” Spotify Advertising, accessed February 4, 2023,

https://ads.spotify.com/en-US/music-marketing/.

6

See, “Music and Streaming Final Report,” Competition & Markets Authority (CMA), November 29, 2022, p.

61. CMA’s analysis shows that “…around 20% of streams were from playlists provided by the music streaming

services (as opposed to playlists created by the users themselves) and a further 11% of streams were delivered

through autoplay function on music streaming services or ‘stations/radio’ provided by music streaming

services.”

10

Best known are the major record companies, whose labels can provide the artists on their rosters

an extensive set of services that, should the artists choose them, might prove helpful to their efforts

to find success in the music business. But a contract with a major record company label is far from

the only path to commercial success. While independent labels cannot come close to matching the

scale of a major record company, the larger ones can offer their artists a comparable set of services

as the major’s labels and the smaller ones often partner with independent services suppliers to

accomplish the same goal. And the many artists who work independent of labels can use a mix-

and-match approach to acquire services they need from independent service suppliers on an à la

carte basis.

The artist-services providers briefly described in the preceding paragraph along with the services

they provide are described in more detail in Section II of this report. Because the relationships

among these players and their dealings with artists are complex and multifaceted, it is not possible

to craft laws and policies that serve the public’s interest in the music business without a nuanced

understanding of these relationships and dealings. Critical to that understanding is an appreciation

of the many ways the music industry has changed over the last 20 years.

In the next section we offer a deeper look at the music industry of today and the forces that have

and continue to transform it before delving more deeply in the remainder of this report into the

economics of contracting that should inform the design of music industry policy.

II. The Music Industry Has Changed Dramatically in the Last 20 Years

For much of the 20

th

Century, and even into the early years of the 21

st

Century, the music industry

was based on a fairly stable business model, a central feature of which was the distribution and

sale of recorded music embedded in various physical media, including vinyl records, audio tapes,

and CDs, that were sold through record stores and other brick-and-mortar retailers. Most music

acquired by consumers was purchased through these outlets, where both the number and the variety

of recordings readily available to consumers were severely constrained by the limited amounts of

retail shelf space. Today the industry’s revenues are primarily comprised of payments for the

11

industry’s share of revenues generated by music streaming services and digital downloads,

7

and

consumers can choose among the many millions of recordings available through online services

that dwarf the variety that even the largest of traditional record stores could offer consumers.

8

As

is described in Section II.A, release and promotion strategies and the ways consumers find and

consume music have all been changed by the shift to online distribution and the industry is still in

the process of reinventing itself in response to these and other changes.

A. The technological drivers of music industry change

Like other parts of the economy, the music industry has been substantially impacted by advances

in information technologies and new services and ways of doing business based on those

technologies. Developments of particular importance to the music industry during the period from

the earliest data employed in the 2002 Wildman Report to the present were the rapid

commercialization of the internet following the National Science Foundation’s initial provision of

points of access that made it possible for commercial networks to interconnect with the internet in

1995;

9

the accelerating trend driven by advances in semiconductors toward ever more powerful

and compact computational devices that led simultaneously to dramatic declines in their costs and

prices; and increased availability and rapid consumer adoption of fixed and mobile communication

services with bandwidth sufficient to support low-latency interactive internet services, including

those that stream entertainment content, both video and audio.

7

BBC news reported that streaming and music downloads accounted for 69 percent of the $26 billion in global

music industry revenues in the year 2021. See Mark Savage, “The global music market was worth $26bn in

2021,” BBC, March 22, 2022, https://www.bbc.com/news/entertainment-arts-60837880; RIAA’s own data

shows that in 2021, streaming and downloads accounted for 87 percent of music revenue in the United States.

8

The difference in magnitude between the diversity of music titles that a physical store can offer in comparison

to the diversity of available digital content is illustrated by analogy to the book industry. Barnes and Noble

brick-and-mortar stores, for example, typically stock between 60,000 and 200,000 book titles. Barnes and

Noble also maintains warehouses across the United States where it stocks “over 1 million titles for immediate

delivery.” In comparison, Barnes & Noble also maintains an online eBook store for its NOOK eReader. This

store offers over 3.6 million titles that are available “anytime, anywhere” on a NOOK device or the Barnes &

Nobel NOOK App. See “Barnes & Noble,” Town Center Plaza & Crossing, accessed February 9, 2023,

https://towncenterplaza.com/stores/barnes-noble; “About Barnes & Noble.com,” Barnes & Noble, accessed

February 9, 2023, https://www.barnesandnoble.com/h/help/about/barnesandnoble; “eBooks & NOOK,” Barnes

& Noble, accessed February 9, 2023, https://www.barnesandnoble.com/b/ebooks-nook/_/N-

8qa?st=PSC&sid=BNB_DRS_Pinterest&2sid=PT&sourceId=PSPTC1.

9

National Science Foundation, “A Brief History of the Internet,” August 13, 2003,

https://www.nsf.gov/news/news_summ.jsp?cntn_id=103050.

12

These developments led first to the widespread use of desktop and laptop computers to download

digital content, including music. Music thus acquired could be played from the computer used to

download it and it could be shared with other music lovers via the transfer of files to other

computers, by burning it to a CD for use with a CD player, or by saving it as an MP3 file that could

be loaded on a portable MP3 player like Apple’s iPod or Microsoft’s Zune. Peer-to-peer

filesharing services, like Napster (launched June 1, 1999

10

) and LimeWire (launched May 3,

2000

11

), facilitated unauthorized transfers of copyrighted material and contributed to the cratering

of music industry revenues in the early 2000s documented below. These services took advantage

of advances in digital technology to make it easy for music users to share music with each other

as MP3 files online. Commercial alternatives, like Apple’s iTunes Music Store, emerged a bit

later to offer consumers a way to legally acquire music from online sources.

12

Developments in digital technology also made it feasible for online service providers to build

computational facilities with the capacity to store massive amounts of user-searchable data at costs

per unit so low that even when much of the content attracted few or even no users, there was a

reasonable expectation that some combination of user payments for access to content and

advertisers’ payments for access to the audiences generated would be more than sufficient to cover

the cost of storing and giving users access to content. The music streaming services are

applications of this business model.

13

Pandora was one of the early applications of this business

model, as were Facebook, YouTube, and Spotify.

10

Stephen Dowling, “Napster Turns 20: How it Changed the Music Industry,” BBC, May 31, 1999,

https://www.bbc.com/culture/article/20190531-napster-turns-20-how-it-changed-the-music-industry.

11

Viktor Hendelmann, “What Happened to LimeWire: What the File-Sharing Service is Up to Now,”

Productmint, accessed January 19, 2023, https://productmint.com/what-happened-to-limewire/.

12

“Apple Launches iTunes Music Store,” Apple Press Release, April 28, 2003,

https://www.apple.com/newsroom/2003/04/28Apple-Launches-the-iTunes-Music-Store/.

13

The differing economics of sales through offline retail establishments versus online sellers was famously

articulated by Chris Andersen in a 2004 article in Wired magazine (“The Long Tail”) and in a 2006 book (The

Long Tail: Why the Future of Business Is Selling Less of More, New York, NY: Hyperion), especially pp. 9, 55,

153. While Anderson’s prediction that relative sales volumes would shift in favor of more niche products at the

expense of mainstream hits has been cast in doubt by subsequent empirical work (see, e.g., Anita Elberse,

“Should You Invest in the Long Tail?,” Harvard Business Review Magazine, July-August, 2008, pp. 88-96), his

thesis that a shift toward online sales would greatly expand the number, range, and diversity of products

available to consumers has been more than borne out. Compare, for example, the millions of book titles

available through Amazon’s bookstore to even the largest brick-and-mortar booksellers whose offerings may

number in the low hundreds of thousands. The reason is that while shelf space for offline retailers, which

13

As the processing power of desktop and handheld devices increased and the bandwidth delivered

to consumers by both wireless and fixed broadband providers increased, the annoyances of

interruptions due to the buffering of streamed content diminished to the point where the consumer

experience listening to streamed music was comparable to listening to traditional radio. Streaming

music also had the added benefits that commercial interruptions were less frequent on ad-supported

streaming services than on commercial radio stations and that ad-free versions of these services

were available for a relatively modest monthly fee. This happened first with personal computers,

but with the introduction of the iPhone in 2007 and the first Android phones in 2008, portable

phones were transformed into high-powered multipurpose computers with the capability to store

and play music files and to stream music over the internet. Today in the United States most people

carry one of these streaming-capable devices in their pocket or purse. According to Statista, in

2021, 95 percent of American adults aged 18-49 owned a smart phone, as did 83 percent of those

age 50-64 and 61 percent of those 65 and above.

14

According to Pew Research, as of 2018, 95

percent of U.S. teens also had access to a smartphone.

15

Entrepreneurs quickly responded to these advances in technology and rapid consumer adoption of

devices capable of receiving streamed content by introducing music streaming services that gave

consumers new ways to listen to music and provided new channels through which artists could

reach listeners. The new streaming services proved popular, and a variety of services soon

emerged to help artists with the placement and marketing of their music on streaming services and

to provide the whole panoply of traditional label services. These developments had a number of

transformational effects on the music industry.

includes not just the shelving but also the building in which it is housed, is expensive and at the margin must

pay for itself through the profit margin multiplied by volume for the item being sold, online storage for digital

products is relatively very cheap.

14

Federica Laricchia, “Share of Adults in the United States Who Owned a Smartphone from 2015-2021,” Statista,

October 18, 2022, https://www.statista.com/statistics/489255/percentage-of-us-smartphone-owners-by-age-

group/.

15

“Smartphone access nearly ubiquitous among teens, while having a home computer varies by income,” Pew

Research Center, May 29, 2018, https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2018/05/31/teens-social-media-

technology-2018/pi_2018-05-31_teenstech_0-04/.

14

B. The distribution and consumption of music have changed

Figure 1, which shows the revenue (in 2021 dollars) generated by music sales to U.S. music

consumers through various distribution formats from 1994 through 2021, reveals a near total

transformation in the ways and forms in which consumers acquired music during this period. CDs,

which were first commercially introduced in Japan in 1982 and in Europe in 1983 and were thus

still a relatively new technology, dominated music sales in the 1990s and into the early 2000s, and,

having already largely displaced vinyl records, were in the process of squeezing music cassettes

from the market as well. By 2004 cassettes, which had accounted for 27 percent of revenues in

1994, were no longer a consequential component of music sales. Online music sales started to

account for a noticeable share of industry revenues beginning in 2005 in the form of digital

downloads, both albums and singles. That singles constituted an appreciable fraction of digital

downloads was a harbinger of the trend toward single track sales rather than albums and EPs.

That trend gained force as purchases from online sources grew and singles soon became the main

format of music consumed, especially as demand shifted increasingly to music streaming services,

where playlists and listening are largely track-oriented. Revenue from online sales first eclipsed

CD sales in 2012 and rapidly became the predominant source of consumer online music

revenues.

16

In 2021 music streaming services accounted for 83 percent of total music sales, with

the remaining 17 percent divided among CDs (four percent), vinyl records (seven percent), which

made a comeback among audiophiles, and the mix of all other types (six percent).

16

CD sales defined as sales of CD albums and CD singles.

15

Figure 1: U.S. Recorded Music Retail Revenue by Format

(1994-2021, Adjusted for Inflation, 2021 Dollars)

Figure 1 also shows how new technologies impacted not only revenues from traditional formats

but total industry revenues during this period. Total revenue peaked in 1999 and then, due to

growing use of unlicensed music file sharing services like Napster and Limewire, entered a period

of steep decline that only started to reverse in 2015 as streaming services like Spotify (launched in

Notes:

[1] As stated by RIAA, the values presented are based on recommended/estimated list prices. For

music formats without a retail list price, the wholesale price was used.

[2] Streaming includes paid subscriptions, limited tier paid subscriptions, ad-supported on-demand

streaming, other ad-supported streaming, and SoundExchange. SoundExchange collects digital

royalties from services such as Pandora and SiriusXM and distributes them to artists and rights

owners. See https://www.soundexchange.com/digital-performance-royalties.

[3] “Other” includes DVD audio, kiosk, SACD, downloaded music videos, physical music videos,

ringtones & ringbacks, synchronization, and other digital sources. For a detailed description of

these and other music formats, refer to RIAA’s website at https://www.riaa.com/u-s-sales-

database/.

Source: CRA analysis of RIAA U.S. Sales Database provided to the authors by RIAA. Compare

to figure available at https://www.riaa.com/u-s-sales-database/.

16

2008

17

), Pandora (which launched its internet radio service in 2005

18

and introduced the Pandora

app in 2008

19

), and Apple Music (launched in 2015

20

) gained traction and quickly became the

leading source of consumer sales, by far. Streaming services accounted for 83 percent of all U.S.

consumer sales revenue in 2021. However, while total industry revenues have recovered from

their low points in the first half of the 2010s, industry revenues are still well below their levels in

the 1990s. Consumers have access to and are consuming more music

21

and are paying

substantially less for it.

The drastic changes in the way music is consumed are also dramatically illustrated by changes in

the format composition of successful recordings. Twenty years ago, most recording achieving the

industry’s highest metrics of success—gold and platinum designations—were albums.

22

By 2018,

the vast majority were singles.

Figure 2, which reports the numbers of singles and albums certified gold or platinum each year

from 2001 to 2004 and from 2018 to 2021, shows how the domination of singles over albums in

17

“About Spotify,” Spotify, accessed February 6, 2023, https://newsroom.spotify.com/company-info/.

18

Michael Arrington, “Pandora to launch next week,” TechCrunch, August 25, 2005,

https://techcrunch.com/2005/08/25/pandora-to-launch-next-week/.

19

MG Siegler, “Pandora solidifies its place as the top iPhone app with its 2 millionth user,” VentureBeat,

December 2, 2008, https://venturebeat.com/social/pandora-solidifies-its-place-as-the-top-iphone-app-with-its-2-

millionth-user/.

20

“Introducing Apple Music — All The Ways You Love Music. All in One Place,” Apple Press Release, June 8,

2015, https://www.apple.com/newsroom/2015/06/08Introducing-Apple-Music-All-The-Ways-You-Love-

Music-All-in-One-Place-/. Apple acquired the Beats Music streaming service with its acquisition of Beats

Electronics in May 2014. Beats Music was shut down by Apple in November 2015 with subscribers having the

choice to migrate to Apple Music and retain their music libraries and playlists. Beats Music was launched in

January 2014. “Apple Is Shutting Down Beats Music On November 30, Forbes, November 13, 2015,

https://www.forbes.com/sites/abigailtracy/2015/11/13/apple-beats-music-headphones-shutting-down-dr-

dre/?sh=2ccb70a55c88. Miriam Coleman, “Beats Music Launching Streaming Service January 21

st

,” January

12, 2014, https://www.rollingstone.com/music/music-news/beats-music-launching-streaming-service-january-

21st-105067/.

21

According to Forbes, citing a study by Nielsen Music, Americans consumed over 36 percent more hours of

music in 2017 than they did even two years earlier, with a trend showing “massive gains from year to year, with

the average expanding by several hours every 12 months.” Hugh McIntyre, “Americans Are Spending More

Time Listening To Music Than Ever Before,” Forbes, Nov.9, 2017,

https://www.forbes.com/sites/hughmcintyre/2017/11/09/americans-are-spending-more-time-listening-to-music-

than-ever-before/?sh=4060bcec2f7f.

22

A recording (e.g., single, short-form album, and full-length album) is certified Gold by the RIAA if it has sold

more than 500,000 units. A recording (e.g., single, short-form album, and full-length album) is certified

Platinum by the RIAA if it has sold more than 1,000,000 units. “Gold & Platinum: About the Awards,”

Recording Industry Association of America, https://www.riaa.com/gold-platinum/about-awards/.

17

aggregate online sales is also reflected in a shift toward singles for gold and platinum

certifications.

23

Today singles account for the bulk of recordings reaching these two milestones.

Figure 2: Composition of Recording Formats by Certification

(2001-2004 and 2018-2021)

The development and rapid rise to predominance of new distribution formats and the

transformation in the ways consumers acquire and consume music are only two of the more visible

ways that advancing information technologies and new services based on those technologies have

changed the music industry. It is fair to say that many of the fundamentals of the music business

have changed. As we discuss in the next subsection, these changes are seen in the options available

to artists at every stage from the production to the distribution of music, in the ways that labels

search for new talent to add to their rosters, in the growing vibrancy of independent labels, and in

23

The search for a standard of comparison that could equate streaming revenues with revenue from the sale of

albums and singles through other channels led to the creation of the revenue-equivalent standard for comparing

a recording’s performance in different distribution channels. For example, the “Billboard 200” albums chart

currently treats 1,250 paid streams and 3,750 ad-supported streams as the revenue equivalent of the purchase of

one album. Gold and platinum certifications and Billboard’s most comprehensive charts are now based on

revenue equivalent measures of success. See Ben Sisario, “The Music Industry’s Math Changes, but the

Outcome Doesn’t: Drake Is No. 1,” New York Times, July 9, 2018,

https://www.nytimes.com/2018/07/09/arts/music/drake-scorpion-streams-billboard-chart.html.

18

the major record companies’ decisions to make sales of services to independent labels and artists

significant components of their businesses.

C. Opportunities for artists and independent labels

The emergence of streaming as the predominant source of music industry revenue opened new

opportunities for artists to make their music available to the music-consuming public. Streaming

services make their money from a combination of advertising placed within the audio streams

distributed by their lowest-tier services, which are typically free to users, and fees paid by

subscribers for the ads-free higher-tier versions of their services. Because the appeal of a streaming

service to its users increases with the number of recordings from which they can choose, the major

music streaming services encourage uploads by virtually anyone with music to which they own

the rights. Artists typically arrange for uploads to be handled by labels or by independent

distribution companies who manage this process and generally collect the revenues artists earn

from streaming for either a fairly low fee or a small share of the revenues they collect.

24

The chance to access at very little cost the streaming services that can distribute music so

efficiently (services that, as noted earlier, account for 83 percent of consumer-driven music

revenue) resulted in an explosion of uploads by artists both well-known and obscure. Figures

released by Spotify, the leading music streaming service, illustrate this point. At the beginning of

2023 the platform offered its users over 80 million songs and 4.7 million podcast titles contributed

by “over 11 million artists and creators.” Over 1,800,000 songs are uploaded during an average

month. Tracks uploaded to Spotify have the potential to reach each of Spotify’s 456 million active

24

For example, CD Baby, DistroKid, and ReverbNation. CD Baby charges $9.95 for releasing a single and

$29.99 for releasing an album for the users of their standard plan, which covers digital distribution to Spotify,

Apple Music, Amazon Music, and more. See, “Pricing,” CD Baby, accessed February 8, 2023,

https://cdbaby.com/cd-baby-cost/. DistroKid charges a subscription fee of $19.99 per year to upload as many

albums and songs as the artist wants, and they will get the artist’s music to all the major streaming services.

See, DistroKid, accessed February 8, 2023, https://distrokid.com/. ReverbNation offers digital distribution to

six retailers (e.g., Spotify, Apple Music, and Deezer), starting at one dollar per single or nine dollars per album

per year. See, “Digital Distribution,” ReverbNation, https://www.reverbnation.com/band-

promotion/distribution.

19

monthly users.

25

As noted earlier, Spotify is just one of a number of prominent music streaming

services, a partial list of which includes Apple Music, Pandora, and Amazon Music Unlimited.

In addition to the upload services mentioned earlier that help artists select and place their music

with streaming services, other services, such as marketing and promotion services (e.g., digital

marketing, promotion, neighboring rights management, synchronization, campaign management

for artists selling music or other items, such as hats and t-shirts off their own websites, and

assistance with direct-to-consumer sales), and distribution services (e.g., sales, digital and physical

distribution, logistics, stock management, and manufacturing), are available to artists striving to

succeed in the music business.

The major record companies, through their labels, offer the artists they sign to recording contracts

upfront financing and the opportunity to acquire most, if not all, of these services through a single

source in exchange for a cut of the revenue the artists generate through sales of their recordings or

in some cases through other activities, such as touring and merchandise sales, that may be

supported by a label. A variety of alternatives have arisen in the marketplace that enable artists to

acquire similar services without a major label recording contract.

With the exception of upfront financing of the artist’s production process, the major record

companies also offer these same services to non-roster artists through their label services divisions.

In addition, larger independent labels can also offer their artists the advantages of one-stop

shopping for similar services, often through a set of affiliated providers. And artists can acquire

similar services from a variety of non-label suppliers as well. Hence, the market provides a variety

of arrangements by which new and established artists may obtain services necessary for producing,

marketing, and performing music.

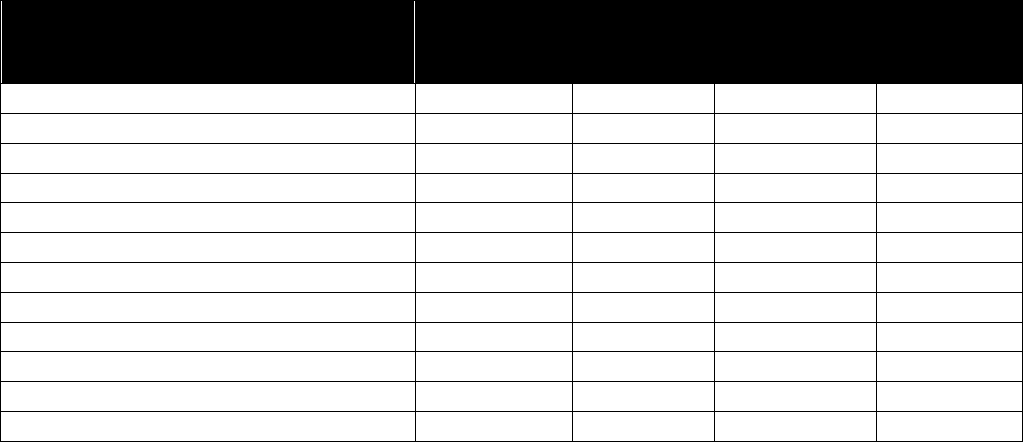

Table 1 lists some examples of independent labels with on-roster artists who have achieved notable

commercial success.

25

Daniel Ruby, “Spotify Stats 2023 (Facts & Data Listed),” Demand Sage, December 30, 2022,

https://www.demandsage.com/spotify-stats/.

20

Table 1: Examples of Alternatives to a Record Deal with a Major Label: Independent Labels

1

Parent

Label Name(s)

Services Provided

Source

A&R

2

Marketing and

Promotion

Wholesale

Distribution

3

Bertelsmann

/ BMG

4

BBR Music Group / Rise Records /

Infectious Music / Vagrant Records /

Trojan Records

[1]

Beggars

Group

4AD / Matador Records / Rough

Trade Records / XL Recordings /

Young

[2]

--

Domino

[3]

--

Brainfeeder

[4]

Secretly

Group

Secretly Canadian / Jagjaguwar /

Dead Oceans / Ghostly International

[5]

--

Asthmatic Kitty

[6]

--

Warp Records

[7]

--

Stones Throw Records

[8]

R&S Records

[9]

Omnian

Music Group

Captured Tracks / 2MR Records /

Manufactured Recordings /

Sinderlyn / Body Double / Fantasy

Memory

[10]

--

Rimas Music

5

[11]

Notes:

[1]

Independent labels are labels that are not owned by one of the big three record companies.

[2]

Talent scouting alone without successive support for artistic development or content creation is not considered A&R for

purposes of this table. We assume that independent labels provide A&R services even if we cannot find explicit mention

of these services on their websites.

[3]

Unless noted, these independent labels have distribution deals with an independent distributor.

[4]

BMG announced in 2016 that it signed a worldwide exclusive distribution deal with Warner's ADA.

[5]

Rimas Music announced a global distribution deal with Sony's The Orchard in 2021.

Sources:

[1]

https://www.bertelsmann.com/news-and-media/news/bmg-confirmed-as-world-s-fourth-largest-music-company.jsp;

https://www.bmg.com/de/publishing.html; https://www.bmg.com/de/recording.html.

[2]

https://www.beggars.com/; https://www.linkedin.com/company/xl-recordings/about/.

[3]

https://www.linkedin.com/company/domino-recording-co-ltd/about/; https://www.dominomusic.com/us;

https://www.musicbusinessworldwide.com/arctic-monkeys-domino-grew-its-uk-turnover-by-31-6-in-2021-driven-by-

strong-catalog-sales/.

[4]

https://www.ninjatune.net/about-us; https://brainfeeder.bandcamp.com/.

[5]

https://deadoceans.com/artists/phoebe-bridgers/; https://deadoceans.com/artists/toro-y-moi/;

https://guitar.com/review/album/the-genius-of-for-emma-forever-ago-by-bon-iver/;

https://shorefire.com/releases/entry/secretly-ghostly-international-announce-new-partnership;

https://www.linkedin.com/company/secretly-group-label/about/.

[6]

https://asthmatickitty.com/artists/sufjan-stevens/; https://asthmatickitty.com/info/;

https://www.imdb.com/name/nm2014294/awards.

[7]

https://www.linkedin.com/company/warp-records/about/; https://www.grammy.com/artists/aphex-twin/18287;

https://warp.net/us/about.

[8]

https://www.linkedin.com/company/stones-throw-records/about/.

[9]

https://www.rsrecords.com/about; https://www.musicweek.com/labels/read/r-s-records-sign-deal-with-believe-

digital/065593.

[10]

https://www.omnianmusicgroup.com/pages/about-us; https://thevogue.com/artists/diiv/;

https://www.manufacturedrecordings.com/contact-us.

[11]

https://www.linkedin.com/company/rimasmusic/about/; https://www.billboard.com/charts/year-end/2022/the-billboard-

200-labels/.

21

Independent labels operating at a relatively small scale may outsource some of their needs,

especially distribution, to a partner company. B2B providers of such services to independent labels

are often referred to as “label services” companies. Some independent artists also need a team

with expertise in marketing, promotion, or distribution to get their music to listeners. Companies,

including some label services companies, that provide such services directly to independent artists

are often called “artist services” providers. Given their overlap, label services companies and artist

services companies are often referred to collectively as artist and label (A&L) services providers.

Typically, like the major and independent labels and the majors’ A&L services divisions, the

service offerings of A&L services providers include A&R, marketing and promotion, and

distribution, with the caveat that the A&R, marketing, and promotion services provided by an A&L

services company are typically a subset of the services provided by a record label’s A&R

division.

26

However, compared to the services of the major or independent labels, A&L services

are more frequently purchased on an à la carte basis and artists’ relationships with these companies

tend to be shorter-term and less comprehensive.

The service that independent artists and labels acquire most frequently from A&L services

companies is distribution,

27

both physical and digital. A&L distribution companies often employ

specialists to provide customized solutions for each artist, which is often a requirement for physical

distribution. For example, Believe, a company that provides digital and other distribution services

to labels and artists, purports to have “…an extensive network of physical distribution partners

around the world and a team of locally based experts who are able to manage and optimize your

physical distribution.”

28

26

“Complete Acquisition by Sony Music Entertainment of AWAL and Kobalt Neighboring Rights Business from

Kobalt Music Group Limited Final Report,” CMA, March 16, 2022 (hereafter, 03/16/2022 CMA Report), p.34,

https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/6231d78dd3bf7f5a8a6955f4/Sony_AWAL_-_Final_Report.pdf.

27

03/16/2022 CMA Report, pp. 7, 33.

28

“Distribution Solutions,” Believe, accessed February 8, 2023, https://www.believe.com/label-artist-

solutions/distribution-solutions.

22

Distribution deals allow the artist to retain their own master rights,

29

while master licensing deals

allow the artist to regain their master rights after the licensing period has expired.

30

Both

essentially grant the artist full control over their music, and therefore differ from traditional label

deals. In the case of distribution deals, the artist (or the independent label that the artist works

with) provides finished recorded materials to a distribution company (see Table 2 for examples of

A&L companies that provide wholesale distribution). The distribution company is responsible for

“… getting the songs and products to retail stores or Digital Service Providers (DSPs).”

31

In return,

the distribution company takes royalties as a percentage of the sales revenue.

32

An artist that is not on roster with a major label may also sign a master licensing deal. In such

cases, the artist will create and record the music after which the artist (or the independent label that

the artist works with) will use marketing services, distribution services, and possibly other services

provided by a larger label to get their music on the market. In return, the larger label gets the

artist’s permission to “…exploit the recordings in different mediums and formats (TV, Film, CD,

Digital, etc.) to generate revenue” for a specified period of time.

33

For example, Olivia Rodrigo,

whose debut single, “Driver’s License,” dominated the Billboard Hot 100 for eight straight

weeks,

34

has control of her original recording rights.

35

Despite the sea-change in the industry described earlier, some aspects of label contractual

arrangements remain as they were 20 years ago. One such notable aspect of label contractual

arrangements is that they typically do not establish a fixed time period for the relationship but

29

“Record Deals and Their Types,” Tunedly, September 29, 2021 (hereafter, 9/29/2021 Tunedly-Record Deals

and Their Types), https://www.tunedly.com/blog/record-deals-and-their-types.html.

30

“What Does it Mean to Own Your Masters?,” amuse, accessed January 31, 2023,

https://www.amuse.io/en/content/owning-your-masters.

31

9/29/2021 Tunedly-Record Deals and Their Types.

32

“What is a Distribution Deal? 8 Pros & Cons to Great Success!,” Track Garden Studio, accessed January 31,

2023, https://trackgardenstudio.com/distribution-deal/.

33

“Recording agreement or licensing agreement?,” The Music Business Blog, September 06, 2021,

https://www.emusicentertainment.net/blog/recordingagreementorlicensingagreement.

34

Callie Ahlgrim, “Only 25 songs in history have debuted at No. 1 on the Billboard Hot 100 and stayed there —

here they all are,” Insider, updated November 8, 2022, https://www.insider.com/number-1-song-debuts-lasting-

runs-billboard-hot-100.

35

Callie Ahlgrim, “Olivia Rodrigo has full control of her masters because she paid attention to Taylor Swift's

battle over her own music,” Insider, May 7, 2021, https://www.insider.com/olivia-rodrigo-owns-master-

recordings-taylor-swift-battle-2021-5. Also, the Spotify page of Olivia Rodrigo’s 2021 Album Sour indicates

that the album is released under an exclusive licensing deal with Geffen Records,

https://open.spotify.com/album/6s84u2TUpR3wdUv4NgKA2j.

23

rather articulate a series of deliverables.

36

The deliverables are defined in the contract to minimize

ambiguity about what the product is that will be the basis for measuring performance and

determining compensation. The terms of contracts typically provide that the artist is entitled to

various forms of payment through the course of the relationship, and the label is entitled to ongoing

reimbursement of its upfront advances and, if full reimbursement is achieved, additional

compensation, depending on how much product the artist produces and its success.

It is uncommon for A&L services companies to offer A&R services, or even marketing and

promotion services, at the scale of full-service record labels. According to a report by the U.K.

Competition & Market Authority (CMA), A&L services companies seldom provide upfront

funding, support for artists’ creative activities, or tour support.

37

Table 2 provides examples of some A&L services companies and identifies their core offerings.

36

These deliverables have historically been (and remain today to be primarily) albums but, as just mentioned,

today the deliverables may also include EPs or even, in some circumstances, singles.

37

03/16/2022 CMA Report, p. 34.

24

Table 2: Examples of Alternatives to a Record Deal with a Major Label: A&L Services Companies

Parent

Company Name(s)

Services Provided

Source

A&R

1

Marketing

and

Promotion

Wholesale

Distribution

Universal Virgin Music Group

2

[1]

Warner

Alternative Distribution

Alliance (ADA)

[2]

Sony

The Orchard

[3]

Sony

AWAL

[4]

--

Believe

[5]

[PIAS] Group

3

[Integral]

[6]

-- EMPIRE

[7]

-- Kartel Music Group

[8]

-- AMPED

[9]

-- RedEye

[10]

Notes:

[1]

Talent scouting alone without successive support for artistic development or content creation is not considered

A&R for purposes of this table.

[2]

Virgin Music Group is Universal’s independent music division which provides label and artist services, and

includes Virgin Music Label & Artist Services, Ingrooves Music Group, and mtheory Artist Partnerships.

[3]

Universal acquired a 49% stake in the [PIAS] Group in 2022.

Sources:

[1]

https://www.virginmusic.com/about/; https://www.universalmusic.com/universal-music-group-launches-virgin-

music-group/.

[2]

https://www.linkedin.com/company/alternative-distribution-alliance/about/;

https://www.musicbusinessworldwide.com/ada-worldwide-reveals-new-leadership-structure-appointing-heads-of-

us-and-international/.

[3]

https://www.linkedin.com/company/the-orchard/about/; https://www.theorchard.com/about/history/.

[4]

https://www.linkedin.com/company/awal/about/; https://www.musicbusinessworldwide.com/sony-musics-430m-

acquisition-of-awal-officially-cleared-by-uk-competition-watchdog/.

[5]

https://www.linkedin.com/company/believeglobal/about/; https://www.believe.com/;

https://www.believe.com/newsroom/believe-and-groove-attack-establish-comprehensive-label-joint-venture-a-

million-music.

[6]

https://www.piasgroup.net/; https://www.integralmusic.com/;

https://www.musicbusinessworldwide.com/universal-acquires-49-stake-in-independent-music-powerhouse-pias/.

[7]

https://www.linkedin.com/company/empire-sf/about/; https://www.grammy.com/news/how-empire-became-

music-industry-giant-unlikely-city.

[8]

https://kartelmusicgroup.com/; https://kartelmusicgroup.com/blog/2019/2/12/funding.

[9]

https://www.linkedin.com/company/amped-distribution/about/; http://www.ampeddistribution.com/about-us.

[10]

https://www.linkedin.com/company/redeye-distribution/about/; https://www.redeyeworldwide.com/.

Thanks to the advances in technology and the prevalence of streaming services, artists nowadays

can also produce music, and release music to a vast audience, using a wide variety of DIY (do-it-

yourself) tools and platforms even without the use of A&L service companies’ offerings. Artists

25

doing so are often called DIY or self-releasing artists, and companies providing tools or platforms

to facilitate self-releasing are called DIY artist services companies. Different from labels which

are more full-service and more “high-touch” (i.e., more focused on personal interaction with the

artists), and A&L services companies, which can be thought of as more “medium-touch”

providers, DIY artist services providers are characterized by low-touch content creation,

marketing, promotion, and distribution services accessed through a common online interface using

a PC or smartphone. As mentioned earlier, for $19.99/year DistroKid will allow an artist to

distribute an unlimited number of albums and songs to all the major streaming services, including

Apple Music and Spotify.

38

Sage Audio is a mastering studio that offers sound engineering and

mastering services, both in-person and online, where artists can upload their songs through a web-

based file transfer system.

39

Sonicbids is an online marketplace that helps artists build their EPKs

(Electronic Press Kits

40

) and land gigs worldwide.

41

Table 3 provides examples of DIY artist

services providers.

Notably, the delineation among these segments (i.e., full-service labels, A&L services, and DIY

artist services) is blurring because companies of all three types have begun offering services

traditionally associated with the other types of companies. Some A&L services companies do

provide recoupable advances for recording and marketing; Kartel Music Group is an example.

42

Some also have their own full-service labels that leverage their in-house distribution platforms.

For example, ONErpm offers marketing and career development services in addition to their core

distribution services. Artists who wish to benefit from the most comprehensive end of ONErpm’s

service spectrum (which the company refers to as “Next Level”) can obtain “full-service customer

career development planning and execution,” including production support, A&R development,

38

See, DistroKid, accessed February 8, 2023, https://distrokid.com/.

39

“Sage Audio Mastering,” Sage Audio, accessed February 8, 2023, https://www.sageaudio.com/.

40

“An Electronic Press Kit (EPK) is a resume or CV for music artists. It is designed to provide labels, agents,

music supervisors, venue talent, buyers and the media with essential information to understand who you are as

an artist so that you can get noticed, land a gig and/or make connections.” See, Deirdre O'Donoghue, “What Is

an EPK (Electronic Press Kit)? (+How to Make One),” G2, February 28, 2019,

https://www.g2.com/articles/epk.

41

Sonicbids, accessed February 8, 2023, https://www.sonicbids.com/.

42

“Funding,” Kartel, accessed February 8, 2023, https://kartelmusicgroup.com/blog/2019/2/12/funding.

26

marketing, promotion, and distribution, which makes “Next Level” service essentially an

equivalent to an independent label.

43

Some DIY services serve not only independent artists, but also have been utilized by independent

labels to promote and distribute their on-roster artists’ music. One example is Bandcamp.

Compared to other major streaming services like Spotify, Bandcamp, according to its website, is

more akin to “a record store and a music community”: artists can have their own homepages on

which they offer streaming of their music and sell digital and physical singles, albums or other

merchandise directly to their fans;

44

while independent labels can have homepages to market and

showcase the music of their roster artists, and also sell their music. Indeed, Bandcamp offers other

services to independent labels, including vinyl pressing (financing, production, and fulfillment),

territorial licensing, targeted fan communication, and real-time statistics.

45

Table 3 provides examples of DIY services providers and identifies some of the types of services

they advertise.

43

“How it Works,” ONErpm, accessed February 8, 2023, https://onerpm.com/how-it-works.

44

“About us,” Bandcamp, accessed February 8, 2023, https://bandcamp.com/about.

45

“Bandcamp for Labels,” Bandcamp, accessed February 8, 2023, https://bandcamp.com/labels?from=hplabels.

27

Table 3: Examples of Alternatives to a Record Deal with a Major Label: DIY Artist Services

Company Name

Services Provided

Source

Content

Creation

1

Marketing and

Promotion

Wholesale

Distribution

UnitedMasters

[1]

DistroKid

[2]

CD Baby

[3]

ONErpm

[4]

Ditto Music

[5]

amuse

[6]

Record Union

[7]

Sonicbids

[8]

beatBread

[9]

Fiverr

[10]

Sage Audio

[11]

Bandcamp

[12]

Notes:

[1]

Content creation refers generally to services that support artistic development, such as: sound recording, producing, or

funding.

Sources:

[1]

https://unitedmasters.com/about.

[2]

https://www.linkedin.com/company/distrokid/about/; https://news.distrokid.com/goodies-f371fd2ae3c8.

[3]

https://www.linkedin.com/company/cd-baby/about/.

[4]

https://www.linkedin.com/company/onerpm/about/.

[5]

https://www.linkedin.com/company/ditto-music/about/.

[6]

https://www.musicbusinessworldwide.com/lil-nas-x-rejected-a-1-million-plus-deal-with-amuse-before-signing-to-

columbia-records/;

https://www.amuse.io/en/content/how-to-get-signed.

[7]

https://www.linkedin.com/company/record-union/about/.

[8]

https://www.linkedin.com/company/sonicbids/about/.

[9]

https://www.beatbread.com/.

[10]

https://www.fiverr.com/ .

[11]

https://www.sageaudio.com/faq.php.

[12]

https://bandcamp.com/about.

At the same time that distribution was becoming more democratized, artists were creating their

own social media presences and building websites to connect directly with fans. From these

websites, fans can also sample tracks from an artist’s recordings and, if they want, purchase them

directly as downloads. Demonstrated success on streaming services and online connections with

a loyal fanbase are a source of bargaining leverage for artists considering a label deal for the first

time. Connections established with fans and the ability to maintain those connections using social

28

media and other online resources without the support of a label should also raise the compensation

bar for labels’ roster artists when it is time to consider renewing their contracts.

46

Online services also offer consumers tools for searching among the myriad artists and songs from

which they can choose. With Spotify’s search tools, for example, it is possible to filter music by

year of release, by artist, by album, by individual track, and by genre, and these filters can be

combined to further narrow a search.

47

Search tools made it possible for music fans to discover

recordings and artists they might never have encountered before digital distribution became the

norm while at the same time giving artists a new way to find an audience and build a fan base.

Streaming service customers can also listen to curated playlists, which has proven to be another

effective way to discover artists they otherwise might never have found. The more influential

playlists have been credited with breaking new stars.

48

In January 2022, the British group Glass

Animals became the first British band to reach the top of Spotify’s top global song chart–this

despite not receiving much support from radio or the written media. The band described streaming

services as “level[ing] the playing field.”

49

46

Rick Hendrix, a consultant and advisor to artists, makes these points in an interview with Forbes. According to

Hendrix, “In many ways, social media and streaming platforms have made talent and potential talent more

visible. It has also given artists an option and reduced the leverage that labels traditionally had over them.” In

addition, he explains, “Artists are now positioned better and can often attract some degree of success before

labels get to them, this way they come to the table with a loyal followership and can add directly to the bottom

line.” Josh Wilson, “The Age Of Digital; Music Executive Reacts To The Impact Of Digitalization In The

Music Industry,” Forbes, September 14, 2022, https://www.forbes.com/sites/joshwilson/2022/09/14/the-age-of-

digital-music-executive-reacts-to-the-impact-of-digitalization-in-the-music-industry/?sh=5b5da34e537b.

47

See Mark Harris, “How to Use Spotify’s Advanced Search Options,” Lifewire, October 29, 2021,

https://www.lifewire.com/tips-on-using-spotifys-advanced-music-search-options-2438840. For a description of

similar search functions for Apple Music and the iTunes Music store, see Markos, “How to Browse for Music

Genres on iTunes,” Boysetsfire, November 9, 2022, https://www.boysetsfire.net/how-to-browse-for-music-

genres-on-itunes/.

48

For an example of how inclusion in an influential playlist can help jumpstart a previously obscure artist’s

career, see Steven Bertoni, “How Spotify Made Lorde a Pop Superstar,” Forbes, November 26, 2013,

https://www.forbes.com/sites/stevenbertoni/2013/11/26/how-spotify-made-lorde-a-pop-

superstar/?sh=5955969276b4.

49

Peter Robinson, “Streams ahead: the artists who made it huge without radio support,” The Guardian, December

1, 2016, https://www.theguardian.com/music/2016/dec/01/artists-made-it-huge-streaming-spotify-apple-music;

Rachel Aroesti, “‘Our managers were like: it’s going to be a dud’: how Glass Animals became the biggest

British band in the world,” The Guardian, January 28, 2022,

https://www.theguardian.com/music/2022/jan/28/our-managers-were-like-its-going-to-be-a-dud-how-glass-

animals-became-the-biggest-british-band-in-the-world.

29

Independent labels

50

and artists building careers without signing with a label benefitted from these

developments. Independent labels quickly cultivated the capabilities and expertise needed to

distribute and promote their contract artists on the online music services and were able to expand

their businesses by selling these services to artists that were not on their rosters. A further benefit

to independent labels is that the streaming services give less well-known artists on their rosters

access to members of an extensive online audience that might never have encountered their music

in a traditional music store.

Self-releasing artists who work without labels, including some who preferred that status, have also