1

INFORMATION DIGNITY ALLIANCE

Megan Keenan

Oregon State Bar No. 204657

(pro hac vice pending)

P.O. Box 8684

Portland, Oregon 97207

Phone: (925) 330-0359

Megan@InformationDignityAlliance.org

Attorney for Plaintiff

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK

DOEMAN MUSIC GROUP MEDIA AND

PHOTOGRAPHY LLC, on behalf of itself

and others similarly situated,

Plaintiff,

v.

DISTROKID LLC, KID DISTRO

HOLDINGS, LLC D/B/A DISTROKID,

RAQUELLA “ROCKY SNYDA” GEORGE,

Defendants.

Case No. 1:23-cv-04776

CLASS-ACTION COMPLAINT FOR

BREACH OF FIDUCIARY DUTY AND

BREACH OF THE COVENANT OF

GOOD FAITH AND FAIR DEALING,

AND

COMPLAINT FOR KNOWING AND

MATERIAL MISREPRESENTATIONS

IN COPYRIGHT NOTICE-AND-

TAKEDOWN REQUESTS

JURY TRIAL REQUESTED

Case 1:23-cv-04776-VEC Document 1 Filed 06/07/23 Page 1 of 34

2

CONTENTS

I. NATURE OF THE CASE ....................................................................................................... 3

II. PARTIES TO THE CASE ....................................................................................................... 4

III. JURISDICTION & VENUE ................................................................................................... 5

IV. GLOSSARY ............................................................................................................................ 7

V. STATEMENT OF FACTS ...................................................................................................... 8

A. In the 1990s, Congress enacted the DMCA to address copyright law’s looming infringement

problem posed by the Internet. .................................................................................................................. 8

B. The Music Industry: Major Labels and Signed Artists v. ILIAs .................................................... 10

C. Takedown Requests Differ for Major Labels and ILIAs ................................................................ 12

a. Major Labels and Major Artists have Aligned Interests when Dealing with Takedown Requests

12

b. ILIAs Interests Do Not Always Align with Music Distributors ................................................ 13

D. ILIAs Depend Upon Music Distributors, including DistroKid, and Music Distributors, including

DistroKid Wield Extraordinary Power over the ILIAs ............................................................................ 14

E. Doeman Music Group is an ILIA ................................................................................................... 18

F. Doeman relied on DistroKid ........................................................................................................... 18

G. Creation of “Scary Movie” ............................................................................................................. 20

H. Ms. George’s Knowingly False Takedown Request ...................................................................... 21

I. DistroKid’s Response to the 512 Takedown .................................................................................. 23

VI. CLASS ACTION ALLEGATIONS ...................................................................................... 27

VII. CAUSES OF ACTION .......................................................................................................... 30

VIII. PRAYER FOR RELIEF ................................................................................................... 33

IX. JURY DEMAND ................................................................................................................... 34

Case 1:23-cv-04776-VEC Document 1 Filed 06/07/23 Page 2 of 34

3

Plaintiff Doeman Music Group Media and Photography LLC brings this action on behalf

of itself and on behalf of a class defined herein of others similarly situated against Defendants

DistroKid LLC and Kid Distro Holdings, LLC d/b/a DistroKid (collectively “DistroKid”), and on

behalf of itself against Ms. Raquella “Rocky Snyda” George based upon personal knowledge, upon

information and belief where applicable, and upon the investigation of counsel.

I. NATURE OF THE CASE

1. This is a case bringing claims under 17 U.S.C. § 512(f) for abuse of the Digital

Millennium Copyright Act (“DMCA”) notice-and-takedown procedures codified at 17 U.S.C.

§ 512(c). It is also a case about a company’s wrongful and harmful acquiescence to abuses of the

DMCA notice-and-takedown system, in violation of that company’s fiduciary duties and duties of

good faith and fair dealing. This company’s wrongful actions leave a vulnerable class of

independent artists and labels powerless to distribute their own music even though they had

contracted with—and paid—this company for that very purpose, i.e., to get their music distributed

on a wide array of platforms. In that regard, this is a case about that company’s rank refusal to do

so much as lift a finger in providing vulnerable independent artists and labels with the information

necessary to keep their works online when faced with abusive DMCA takedowns.

2. That company, DistroKid, operates as a music distributor—a position of significant

market power operating as the middleman between independent artists and labels (who create

music) and the platforms that supply the music directly to the public (Spotify, Amazon Music,

iTunes, etc.). DistroKid’s power stems from the fact that platforms, like Spotify and iTunes, will

not allow independent artists and labels to post their music to the platforms directly, requiring them

to instead go through music distributors. This market dynamic leaves independent labels and

artists subject to the whims and preferences of a music distributor like DistroKid.

Case 1:23-cv-04776-VEC Document 1 Filed 06/07/23 Page 3 of 34

4

3. A music distributor like DistroKid’s refusal to make any reasonable effort in line

with its duties to assist artists and independent labels with information about notice-and-takedowns

results in artists’ financial and reputational ruin. And the harm goes further. Indeed, the public at

large suffers too because tens of thousands of listeners lose access to the music that they want to

listen to.

4. Despite the notice-and-takedown procedures set forth in 17 U.S.C. § 512(c)

creating an out-of-court system to resolve a majority of disputes, the music distributor’s

indifference to the procedures leaves the harmed the artists and labels with legal course as their

only option.

II. PARTIES TO THE CASE

5. Plaintiffs. Named Plaintiff Doeman Music Group Media & Photography LLC is a

West Virginia limited-liability company with a principal place of business in West Virginia

(“Doeman”). At present, Doeman is unaware of the domicile of the unnamed class members

similarly situated to itself.

6. Defendants. DistroKid LLC is a Delaware limited-liability company with a

principal place of business in the Southern District of New York. Likewise, Kid Distro Holdings

LLC d/b/a DistroKid is, on information and belief, a Delaware limited-liability company with a

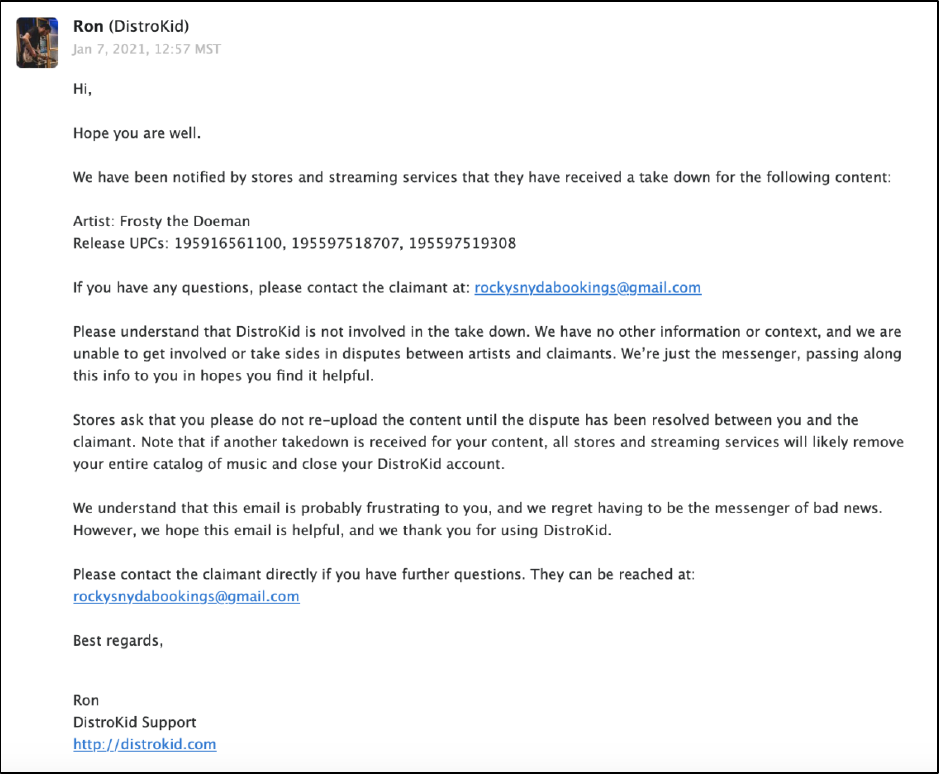

principal place of business in the Southern District of New York. Ms. George is, on information

and belief, domiciled either in the Southern District of New York (the Bronx) or the Eastern

District of New York (Brooklyn).

Case 1:23-cv-04776-VEC Document 1 Filed 06/07/23 Page 4 of 34

5

III. JURISDICTION & VENUE

7. Subject-Matter Jurisdiction. This Court has subject-matter jurisdiction because

the claims in suit involve federal questions as well as related state-law claims that themselves

involve diverse parties with a sufficient amount in controversy.

a. Federal-Question Jurisdiction: Doeman’s claims against Ms. George for knowing

and material misrepresentations in her notice-and-takedown requests arise under an act of

Congress relating to copyrights, i.e., under 17 U.S.C. § 512(f). Therefore, this Court has exclusive

subject-matter jurisdiction over these claims. See 28 U.S.C. §§ 1331 (federal-question

jurisdiction), 1338(a) (exclusive jurisdiction over copyrights).

b. Supplemental Jurisdiction: Doeman’s New York common-law claims against

DistroKid for breach of fiduciary duty and for breach of the implied covenant of good faith and

fair dealing are so related to the claims against Ms. George that they form part of the same case or

controversy. Therefore, this Court has supplemental jurisdiction over these claims. See 28 U.S.C.

§ 1367(a).

c. Ordinary Diversity Jurisdiction: Doeman’s New York common-law claims against

DistroKid arise between diverse parties. Doeman is incorporated in West Virginia with a principal

place of business in West Virginia. DistroKid is incorporated in Delaware with, on information

and belief, a principal place of business in New York. Likewise, Ms. George is, on information

and belief, domiciled in New York. Thus, there exists complete diversity of citizenship between

the Parties. 28 U.S.C. § 1332(a)(1), (c)(1). And, the amount in controversy exceeds $75,000. 28

U.S.C. § 1332(a).

d. Class-Action Diversity Jurisdiction: This Court also has jurisdiction under 28

U.S.C. § 1332(d)(2)(b).

Case 1:23-cv-04776-VEC Document 1 Filed 06/07/23 Page 5 of 34

6

8. Personal Jurisdiction. DistroKid is domiciled in the State of New York. Ms.

George is as well. Therefore, Defendants are subject to the jurisdiction of a court of general

jurisdiction in the State of New York. N.Y. C.L.P.R. § 301 (authorizing the exercise of

“jurisdiction over persons, property, or status as might have been exercised” on or before

September 1, 1963); e.g., Rawstorne v. Maguire, 192 N.E. 294, 295 (N.Y. 1934) (“The courts of

the State can obtain jurisdiction of the persons of those who are domiciled within the State[.]”).

Upon service of summons or waiver thereof, this Court will have personal jurisdiction over

Defendants. See Fed. R. Civ. P. 4(k)(1)(A).

9. Venue. All Defendants are residents of the State of New York. DistroKid resides

in the Southern District of New York. See 28 U.S.C. § 1391(c)(2). Ms. George resides, on

information or belief, either in the Southern District of New York (the Bronx) or the Eastern

District of New York (Brooklyn). See 28 U.S.C. § 1391(c)(1). Moreover, a substantial part of the

events and omissions giving rise to the claims occurred in this District. Therefore, this District is

a proper venue. See 28 U.S.C. § 1391(b)(1)-(2).

10. Intra-District Assignment. None of the claims asserted herein arose in whole or

in major part in the Northern Counties of this District. Likewise, none of the named Parties reside

in the Northern Counties. Therefore, under this Court’s Rules for the Division of Business Among

District Judges, this case is appropriately assigned to Manhattan. See Rule 18(a)(3)(C) (Civil cases

not meeting the criteria for assignment to White Plains under Rule 18(a)(3)(A)-(B) “shall be

designated for assignment to Manhattan.”).

Case 1:23-cv-04776-VEC Document 1 Filed 06/07/23 Page 6 of 34

7

IV. GLOSSARY

Defined Term

Definition

Takedown

Request

The request received by a platform to take down a work pursuant to the

notice and takedown procedures set out in ¶16 and 17 U.S.C. § 512. This

definition includes a false takedown that falls within 17 U.S.C. § 512(f).

Distribution

Agreement

The DistroKid Distribution Agreement is its form contract supplied on its

website and also accepted by each ILIA upon upload of a new song or album

using DistroKid’s music distribution service.

DMCA

Digital Millennium Copyright Act

Doeman

Doeman Music Group Media & Photography LLC, a West Virginia limited-

liability company with a principal place of business in West Virginia

ILIA

Independent record labels and independent artists that self-distributes music,

i.e., not a major label.

Major Labels

The three largest record labels, Universal Music, Sony Music, and Warner

Music.

Music

Distributor

A company that charges ILIAs a fee to populate music to a variety of

streaming services, online music stores, and other Platforms. Defendant,

DistroKid is a Music Distributor.

Platforms

Any business that offers an online website that relies upon, shares, and

distributes content, without modification to the content, posted by its users:

e.g., Facebook, Instagram, TikTok, YouTube, Spotify, etc.

Case 1:23-cv-04776-VEC Document 1 Filed 06/07/23 Page 7 of 34

8

V. STATEMENT OF FACTS

A. In the 1990s, Congress enacted the DMCA in response to the looming copyright

infringement problem posed by the Internet.

11. In the mid-1990s, Congress realized that a massive problem was looming with the

adoption of the Internet; copyright infringement could, and would, scale at an unprecedented rate.

Copyrightable works could be copied with almost no cost, and infringing copies could be

frictionlessly distributed across the Internet instantaneously. As a strict-liability tort, Copyright

law could make every instance of copying a federal lawsuit against the posting party and the

Platform that hosted the infringing content. This inevitable proliferation of copyright infringement

would wreak havoc for three key stakeholders: copyright holders, federal courts, and Platforms.

12. Copyright holders faced the risk of massive amounts of infringement. The

Internet’s global reach and frictionless copying endangered copyright holders’ rights with

unprecedented ease. One copy posted online could multiply into hundreds or thousands of copies

instantaneously all across the Internet. To protect their rights, copyright holders would have to go

to court to obtain an injunction to stop each infringing copy. Thus, a copyright holder could have

to file hundreds or thousands of lawsuits to stop what started out as one posted infringing copy of

a work. But, the cost of representation can be high to appear in federal court, and many copyright

holders may not have the means to bring suit, or would be forced to represent themselves pro se.

13. Federal courts faced the risk of a deluge of pro se copyright litigation dealing with

each copyright holder’s hundreds or thousands of lawsuits for injunctive relief. Given federal

courts’ exclusive federal jurisdiction over copyright claims, such online infringements would

inundate federal dockets.

Case 1:23-cv-04776-VEC Document 1 Filed 06/07/23 Page 8 of 34

9

14. Platforms faced the risk of secondary liability for each infringing copy uploaded to

their website by an infringing user. Thus, the Internet’s scale and the difficulty of moderating user

content paired with the proliferation of copyright infringement meant that Platforms faced

potentially ruinous liability for the acts of their users.

15. Foreseeing these issues on the horizon, Congress created an elegant solution

codified in 17 U.S.C. § 512, also known as the Notice-and-Takedown System. This system was

meant to keep the majority of online infringement disputes out of courts saving each stakeholder

resources.

16. The Notice-and-Takedown System works as follows.

a. A posting party posts a work on a Platform. A copyright holder sees the

work on a Platform and identifies the work as an infringement of their copyright.

b. The copyright holder can notify the Platform of the infringing copy. Instead

of filing a case in federal court for an injunction, copyright holders can submit a simple

form directly to the Platforms to request the removal of infringing content. 17 U.S.C. §

512(c)(3)(A). (Exhibit A to this Complaint is a sample takedown request available on the

U.S. Copyright Office website).

c. The Platform would receive the request and expeditiously remove the

content from its website. 17 U.S.C. § 512(c)(1)(A). Subsequently, it would inform the

posting party that the content had been removed. 17 U.S.C. § 512(g)(2)(A).

d. If the posting party believes that the takedown was made by mistake or

misrepresentation, then the posting party can submit a counter-notification stating so. 17

U.S.C. § 512(g)(3).

Case 1:23-cv-04776-VEC Document 1 Filed 06/07/23 Page 9 of 34

10

e. Once the Platform receives a counter-notification it must replace the content

within 10-14 days unless it receives notice from the copyright holder, or its agent, that the

copyright holder has filed a case in federal court seeking to restrain the posting party from

infringing the copyright holder’s rights. 17 U.S.C. § 512(g)(2)(C).

17. Congress incentivized Platforms to participate in the Notice-and-Takedown System

by providing a safe harbor for Platforms that comply with the Notice-and-Takedown System. 17

U.S.C. § 512(g).

18. As a result of the Notice-and-Takedown System, federal courts would not be

inundated with infringement claims arising out of third-party content posted on Platforms online,

platforms would not be subject to ruinous liability, and copyright holders could enforce their rights

without the burden and financial strain of filing hundreds of lawsuits.

19. While an elegant solution to all three stakeholders’ problems, Congress still had to

address the issue of abuse of the Notice-and-Takedown System. Given §512’s quasi-injunctive

power, bad actors could weaponize the Notice-and-Takedown System by fraudulently submitting

a Takedown Request and removing content from Platforms that was rightfully posted by the

copyright holder. Thus, Congress created a cause of action for false takedowns, 17 U.S.C. § 512(f).

20. Since its adoption, the Notice-and-Takedown System has been an effective means

of dealing with third-party infringement on the Internet.

B. The Music Industry: Major Labels and Signed Artists v. ILIAs

21. This system has benefited a wide range of industries. One such industry that relies

upon the Notice-and-Takedown System is the music industry. Musical artists have used the Notice-

and-Takedown System as a means to enforce their rights online to protect their recorded music.

But the system works better for some artists than others.

Case 1:23-cv-04776-VEC Document 1 Filed 06/07/23 Page 10 of 34

11

22. For Artists signed with a Major Label, the system works. Yet, for ILIAs it doesn’t.

The difference lies in the market realities for Major Labels and ILIAs and the shift towards

streaming music instead of owning copies.

23. The Internet made way for many music Platforms, like Spotify, iTunes, Pandora,

YouTube, TikTok, iHeartRadio, and Amazon, to provide consumers with instantaneous access to

recorded music. In today’s digital world, individuals can find, play, use, or purchase recorded

music in hundreds of places. For example, suppose you hear a song you like on TikTok. Later,

you listen to that song on your personal Spotify account. Then, you decide to watch the music

video for that song on YouTube. You hear the same song, but you are interacting with it on a

number of distinct Platforms.

24. A music Platform’s success is dependent upon artists uploading their music to a

Platform’s website, i.e., artists are third-party posters that supply content (or music) to Platforms.

These Platforms then provide access to an artists’ recorded music to consumers to find, play, use,

or purchase.

25. Each Platform provides unique consumer experiences while also demanding

different requirements from the artists to post content on them. Indeed, for artists, a fundamental

feature of this digital market for recorded music is its disaggregation. Different Platforms require

different upload formats, have different payment methods, use different reporting, operate in

different languages, etc. In other words, the disaggregation of the market for recorded music leads

to massive administrative complexities for artists.

26. Artists can populate these music Platforms in two ways. An artist can sign with a

Major Label, or the artist can self-distribute using an independent label or individually.

Case 1:23-cv-04776-VEC Document 1 Filed 06/07/23 Page 11 of 34

12

27. Major Labels are self-contained entities that can post music online directly to

Platforms. Whereas ILIAs must work with music distributors to post music to Platforms.

C. Takedown Requests Differ for Major Labels and ILIAs

a. Major Labels and Major Artists have Aligned Interests when Dealing with Takedown

Requests

28. Major Labels control much of the market for recorded music and have the resources

and staff to post and monitor their artists’ online musical content. The biggest artists like Taylor

Swift, Drake, Rihanna, etc., all sign with Major Labels.

29. Because the Major Labels control much of the market for recorded music, Major

Labels use their expertise and resources to negotiate royalty terms with, and post music directly

onto, Platforms like Spotify and YouTube. Major Labels are in the business of promoting their

artists and the Major Labels benefit when their artists are successful. Indeed, Major Labels are

invested in their artists and take an interest in an artist’s reputation, fans, and ability to reach new

listeners. And, Major Labels have an interest in ensuring that listeners can access their artists’

music. Thus, Major Labels and their artists have aligned interests. Both parties share a holistic

interest in the artists’ success and both parties benefit from posting the artists’ music and ensuring

that the music is available for listeners to stream and purchase.

30. Thus, because artists and Major Labels have aligned interests, the standard Notice-

and-Takedown System works because the Major Label wants to ensure that the artists’ music stays

up. Major Labels meet their contractual obligations and their fiduciary duties to artists because the

Major Labels ensure that the music that they are charged with taking care of and posting on behalf

of the artist is populated on applicable streaming services and kept posted.

Case 1:23-cv-04776-VEC Document 1 Filed 06/07/23 Page 12 of 34

13

31. For example, take a look at Taylor Swift. Taylor Swift is one of the most streamed

artists on Platforms like Spotify and YouTube. If a takedown party sends Spotify a Takedown

Request for Taylor Swift’s music, her record label would use its expertise and resources to take

immediate and necessary corrective action to avoid having the music removed from Spotify. Her

Major Label would send a counter-notice as fast as it could. By doing so, the music does not get

taken down—and her fans can continue to listen to her music and her royalties continue to accrue.

b. ILIAs Interests Do Not Always Align with Music Distributors

32. Major Labels are not the entire music industry. Today, many artists represent

themselves or sign with small independent labels.

33. Where the Major Labels have the resources and expertise to manage the multitude

of formats and requirements necessary to upload music and to negotiate directly with streaming

services, the same is not true of ILIAs. Thus, ILIAs rely upon Music Distributors, like DistroKid.

Indeed, some streaming services and online stores require that ILIAs upload music using a Music

Distributor.

34. In the Notice-and-Takedown System, the interests of ILIAs and Music Distributors

are not as in sync and aligned as the interests of Major Labels and its artists. When an ILIA uploads

music to a Platform using a Music Distributor, the Music Distributor does not have the same

investment in the ILIA as the Major Label has with its artists. Music Distributors are not invested

in the holistic success of small artists and labels as Major Labels are with their artists. Indeed,

Music Distributors are not dependent upon the success of an ILIA’s music amongst listeners.

35. A Music Distributor may not have a financial incentive aligned with an ILIA’s

music staying posted online. A Music Distributor like DistroKid collects money upfront and

annually. And it offers extra services, for extra fees, when an ILIA uploads music. Thus, after the

Case 1:23-cv-04776-VEC Document 1 Filed 06/07/23 Page 13 of 34

14

music has been posted, there is little financial incentive for a Music Distributor like DistroKid to

take extra measures to ensure that music stays up.

36. DistroKid, and Music Distributors generally, have little to no interest in an ILIA’s

reputation, its fans, or its ability to reach new listeners.

37. And, even if a Music Distributor requires a percentage of royalties, such payments

for many ILIAs can be incredibly small. So, keeping the music posted online does not necessarily

benefit a Music Distributor because streams can be so low as to not provide financial value.

38. Oftentimes, after the initial upload of the music to a Platform, a Music Distributor

has little to no continuing internal financial reason to expend resources ensuring that the music

continues to stay posted. Especially in the context of small ILIAs that do not generate large income

from streaming music on Platforms.

D. ILIAs Depend Upon Music Distributors, including DistroKid, and Music Distributors,

including DistroKid Wield Extraordinary Power over the ILIAs

39. Music Distributors bring industry expertise and specific knowledge to ILIAs.

40. Music Distributors contract directly with Platforms and negotiate terms and

procedures, so the Platforms don’t have to negotiate separately with every ILIA that wants to

upload music to Platforms’ websites.

41. ILIAs do not have access to the terms or negotiations between Music Distributors

and Platforms.

42. Music Distributors communicate with the Platforms that they upload music to,

including about music uploaded by DistroKid on behalf of ILIAs.

43. ILIAs are not included in, nor given access to, such communications.

Case 1:23-cv-04776-VEC Document 1 Filed 06/07/23 Page 14 of 34

15

44. Music Distributors have specialized knowledge on how to upload music to a variety

of Platforms. Music Distributors leverage this industry expertise and specialized knowledge to

create a uniform system for Platforms to onboard ILIAs.

45. ILIAs do not have such specialized knowledge and must rely upon Music

Distributors to upload to a variety of Platforms. Music Distributors are not only for convenience.

Some Platforms, like Spotify and iTunes, will not allow ILIAs to upload music directly on their

platform. These Platforms require ILIAs to upload music through a Music Distributor.

46. An ILIA’s ability to populate music on a variety of music platforms is critical to

any artist’s success. Having a song or album on Platforms like Spotify, iTunes, Pandora, or TikTok

gives an artist legitimacy and the ability to promote their music, keep fans, and obtain new ones.

47. In today’s digital world, an ILIA can find it virtually impossible to promote its

music if it is not on Platforms like Spotify, iTunes, Pandora, or TikTok. Indeed, in 2022 84% of

revenue from music distribution came from online streaming. Simply put, ILIAs must be present

in online streaming platforms to stay competitive and have the opportunity to share their music

with the consuming public.

48. ILIAs are entirely dependent upon Music Distributors to promote their music since

Music Distributors are the intermediary between Platforms and ILIAs. And, Music Distributors

have the ability to remove ILIA’s music from the Platforms that is populates.

49. Music Distributors are not only charged with populating ILIAs’ music to a

multitude of Platforms, but Music Distributors also collect royalties from these Platforms on behalf

of ILIAs.

50. ILIAs do not have the ability to set royalty rates for the music uploaded to Platforms

using DistroKid.

Case 1:23-cv-04776-VEC Document 1 Filed 06/07/23 Page 15 of 34

16

51. DistroKid is a Music Distributor. And, DistroKid wields extraordinary power over

the ILIAs that pay for and use its music distribution service.

52. DistroKid has industry expertise and specific knowledge about music streaming

and the distribution of music to Platforms.

53. DistroKid contracts directly with the Platforms that it populates and negotiates

terms and procedures.

54. The ILIAs that use DistroKid as a music distributor do not have access to the terms

or negotiations between DistroKid and the Platforms it uploads music to.

55. DistroKid communicates with the Platforms it uploads music to, including about

music uploaded by DistroKid on behalf of ILIAs.

56. ILIAs are not included in, nor given access to the communications between

DistroKid and the Platforms that it uploads music to.

57. DistroKid has specialized knowledge on how to upload music to a variety of

Platforms. DistroKid leverages its industry expertise and specialized knowledge to create a

uniform system for Platforms to onboard ILIAs.

58. ILIAs that pay for DistroKid’s services do not have such specialized knowledge

and must rely upon DistroKid to upload to a variety of Platforms.

59. ILIAs that pay for DistroKid’s services are entirely dependent upon DistroKid to

promote their music since DistroKid is the intermediary between Platforms and ILIAs. And,

DistroKid has the ability to remove ILIA’s music from the Platforms that it uploads music to.

60. DistroKid also collect royalties from the Platforms that it populates music to on

behalf of ILIAs that pay for DistroKid’s services.

Case 1:23-cv-04776-VEC Document 1 Filed 06/07/23 Page 16 of 34

17

61. ILIAs do not have the ability to set royalty rates for the music uploaded to Platforms

using DistroKid.

62. Even more, DistroKid does not allow a right of accounting to ILIAs. DistroKid’s

form distribution agreement expressly waives an ILIAs’ right to request an accounting regarding

royalty payments paid through DistroKid. Thus, DistroKid has complete control over ILIA’s

royalty payments without any transparency into how it got the money.

63. When an ILIA wants to upload music to a Platform using DistroKid, DistroKid has

control over:

a. All communications from a Platform about an ILIAs’ music;

b. the terms of the agreements between DistroKid and the various

Platforms that effect ILIAs;

c. the terms of the agreements, i.e., the Terms of Use and Distribution

Agreement, between DistroKid and the ILIAs that pay for its

services;

d. all information pertaining to the uploading of music to any music

Platform that DistroKid contracts with;

e. the decision to remove an ILIA’s music from any or all streaming

services;

f. market information;

g. the royalties paid by Platforms to artists; and

h. the accounting for royalty payments.

Case 1:23-cv-04776-VEC Document 1 Filed 06/07/23 Page 17 of 34

18

E. Doeman Music Group is an ILIA

64. Doeman is a West Virginia-based independent record label that operates out of

Martinsburg, West Virginia.

65. Mr. Damien “Frosty the Doeman” Wilson, is a recording artist and songwriter

signed with Doeman and its publishing arm. Mr. Wilson is an accomplished hip-hop artist and has

been producing music for nearly two decades. Mr. Wilson has accumulated an expansive

repertoire of music and has extensive experience performing in music venues. Works that Mr.

Wilson created under his recording relationship with Doeman have been performed on Sirius XM,

terrestrial radio stations, and are streamed online to listeners across the globe. Mr. Wilson has

performed in a variety of music venues in the District of Columbia, in West Virginia, and in

Jamaica.

66. Doeman is a full-stack label that offers producing, mixing, mastering, and sound

engineering services that works with a wide variety of artists. Doeman also provides services in

its community to low-income artists by providing its wide array of services to artists that can’t

afford to pay for time in a recording studio.

67. In August 2020, Mr. Wilson’s hit single “Scary Movie” was featured on XM radio’s

Shade 45 station. The song was promoted on the station’s playlist and the station’s Instagram.

F. Doeman relied on DistroKid

68. Doeman chose DistroKid as its Music Distributor. Prior to uploading any music,

Doeman, and others similarly situated, had to create a DistroKid account. Part of the account-

creation process includes picking a plan and making a payment for the annual subscription fee

upfront after payment, and in accordance with DistroKid’s Terms of Use and Distribution

Agreement.

Case 1:23-cv-04776-VEC Document 1 Filed 06/07/23 Page 18 of 34

19

69. The DistroKid Distribution Agreement is a form contract that is required to be

accepted prior to uploading any music. Indeed, DistroKid labels the checkbox as “Mandatory”

requiring its acceptance prior to uploading any music to the DistroKid website. Once the

Distribution Agreement is accepted, an ILIA can upload its song or album to DistroKid, and

DistroKid will distribute the works to its network of Platforms.

70. There is no ability for an ILIA who wants to upload music to negotiate the terms of

the Distribution Agreement or reject any single term. An ILIA either accepts DistroKid’s terms or

does not upload any music to the website. Despite the fact that an ILIA has already paid for its

annual subscription prior to DistroKid presenting the Distribution Agreement upon uploading

music.

71. In July 2020, Doeman uploaded the extended play (“EP”) Halloween-themed

“Murder Season Vol.1” and a single included in the album titled “Scary Movie.”

72. Before uploading this music, DistroKid required Doeman to agree to its

Distribution Agreement. Doeman agreed and uploaded this music to DistroKid. DistroKid then

populated various Platforms with Doeman’s music.

73. Doeman relied upon DistroKid’s inside-knowledge and expertise to upload “Scary

Movie” and “Murder Season Vol. 1” onto streaming platforms like Spotify, iTunes, Amazon, etc.

Case 1:23-cv-04776-VEC Document 1 Filed 06/07/23 Page 19 of 34

20

74. Doeman relied upon DistroKid to contract with the streaming services to upload its

music.

75. Doeman relied upon DistroKid to provide guidance on what it needed to do in order

to post music on Platforms.

76. Doeman relied upon DistroKid to properly format its music to each individual

Platform.

77. Doeman relied upon DistroKid to keep in contact with streaming services and pass

along any information a streaming service provides to DistroKid about its music.

78. Doeman relied upon DistroKid to upload music on its behalf to the streaming

services that DistroKid contracts with.

79. Doeman relied upon DistroKid to collect royalties from the Platforms on his behalf.

80. Doeman relied upon DistroKid to pay the royalties that DistroKid collected on

behalf of Doeman.

81. Doeman relied upon DistroKid to ensure that its music was available on the

Platforms.

G. Creation of “Scary Movie”

82. In May 2020, Doeman was working on creating new music, including “Scary

Movie.” Mr. Wilson was put in touch with Defendant, Ms. Raquella George through a close friend.

Mr. Wilson contacted Ms. George and requested that she contribute a short clip of her voice to be

used in his upcoming release, “Scary Movie.” Ms. George agreed.

83. Doeman paid Ms. George in exchange for her work and agreed to include her name

in the credits of the song.

Case 1:23-cv-04776-VEC Document 1 Filed 06/07/23 Page 20 of 34

21

84. Mr. Wilson emailed Ms. George a working version of “Scary Movie.” This working

version has Mr. Wilson singing the portion that Ms. George would simply imitate. Mr. Wilson

also gave Ms. George detailed instructions on what he wanted Ms. George to say in the recording

and how he wanted her to say it. He directed and coached her performance, with ultimate control

over its sounds, final version, etc.

85. Over the next several weeks, Mr. Wilson and Ms. George exchanged numerous

messages and versions of Ms. George’s part of the song. After extensive back and forth, Mr.

Wilson had the three-second clip of Ms. George that he wanted for his song.

86. In July 2020, Mr. Wilson uploaded the single “Scary Movie” and the EP “Murder

Season Vol. 1” (which included “Scary Movie”) to DistroKid for distribution.

H. Ms. George’s Knowingly False Takedown Request

87. After the release of “Scary Movie,” Mr. Wilson and Ms. George had a personal

falling out. A mutual contact had made false statements about Mr. Wilson to Ms. George and had

misrepresented Mr. Wilson to Ms. George to a sufficient degree that Ms. George decided to

retaliate.

88. Because of that falling out and her decision to retaliate, on or around January 7,

2021, Ms. George sent a direct message to Mr. Wilson on Instagram and demanded that her name

be removed from “Scary Movie.” Ms. George wrote:

“Please remove my name as a featured artist on the track ‘Scary Movie’ through your

distribution or I will be forced to issue a take down with my distributor. &This WILL result in the

take down of your entire project as well.

I need my name removed within 24 hours. If I don’t get a screen shot confirmation from

you that I’ve been removed via email I will be forced to proceed with the take down.”

Case 1:23-cv-04776-VEC Document 1 Filed 06/07/23 Page 21 of 34

22

89. Ms. George did not assert to Mr. Wilson that she was in any way the copyright

holder of “Scary Movie.” In fact, she never has asserted to Mr. Wilson that she was in any way the

copyright holder of “Scary Movie” because Ms. George’s message to Mr. Wilson does not convey

such information.

90. Ms. George did not assert that Doeman or Mr. Wilson had infringed any copyright.

In fact, she never has asserted to Mr. Wilson that Doeman or Mr. Wilson had infringed any

copyright ever.

91. Ms. George did not assert that Mr. Wilson had posted “Scary Movie” without

authorization of the copyright holder. In fact, Ms. George never asserted that anyone but Mr.

Wilson or Doeman had posted “Scary Movie” had the power and right to make such a posting

through DistroKid.

92. What Ms. George did do, was use §512 as a weapon to hold Doeman’s music

hostage to her preferences about how Doeman exercise its copyrights. She threatened that if

Doeman didn’t as she wished, she would send a takedown in retaliation.

93. Ms. George threatened to use the Notice-and-Takedown System as set forth in §512

as a weapon to ensure that Mr. Wilson comply with her desire to have her name taken off of the

song, “Scary Movie.”

94. Ms. George used the Takedown Request as leverage to threaten Doeman. Ms.

George knew that when she submitted the Takedown Request, Doeman’s entire EP would be taken

down.

95. Mr. Wilson refused to alter his work to accommodate her request.

Case 1:23-cv-04776-VEC Document 1 Filed 06/07/23 Page 22 of 34

23

96. Indeed, when Mr. Wilson asserted that Ms. George could not submit a takedown

because he was the rightful copyright owner, Ms. George responded by blocking Mr. Wilson on

Instagram.

97. Shortly after this exchange on Instagram, Ms. George submitted a Takedown

Request. Ms. George used the Takedown Request as a weapon in spite to fuel her personal animus

towards Doeman’s principal, Mr. Wilson.

98. It is unknown precisely which platforms Ms. George sent the takedown to. Ms.

George submitted this Takedown Request to Spotify. Ms. George falsely represented that she was

the copyright holder of the song “Scary Movie.” Despite that Mr. Wilson had informed her that

Doeman was the copyright holder. Ms. George blocked Mr. Wilson from messaging in an attempt

to be intentionally willfully blind to the reality that she did not have any rights in “Scary Movie.”

99. On information and belief, Ms. George submitted a Takedown Request to other

Platforms as well.

I. DistroKid’s Response to the 512 Takedown

100. On or around January 7, 2021, on information and belief, DistroKid received a

takedown notice from stores and streaming services pertaining to “Scary Movie.”

101. On information and belief, DistroKid knew the specific streaming services and

stores that reported the takedown notice for “Scary Movie.”

102. On or around January 7, 2021 DistroKid sent Doeman a form message notifying it

of the takedown. The email said the following:

Case 1:23-cv-04776-VEC Document 1 Filed 06/07/23 Page 23 of 34

24

103. DistroKid’s email withheld information from Doeman about the takedown.

104. DistroKid did have more information and context than it provided in its email.

105. DistroKid did not identify which stores and streaming services received a

takedown.

106. DistroKid did not inform Doeman where to submit a counter-notice.

107. DistroKid did not offer any identifying information that would assist Doeman in

submitting a §512 counter-notice.

Case 1:23-cv-04776-VEC Document 1 Filed 06/07/23 Page 24 of 34

25

108. In response to the email, Doeman promptly replied requesting information on how

to get involved in the process and asking additional information on how the dispute was

processed.

109. DistroKid again did not provide information that it did in fact have. In response,

DistroKid stated that:

110. DistroKid did have additional information.

111. Doeman followed up several times in efforts to obtain information from

DistroKid that Doeman could use to get its music back up. DistroKid ignored seven subsequent

messages from Doeman over the next few weeks.

112. Finally, on or around January 24, 2021, DistroKid responded as follows:

Case 1:23-cv-04776-VEC Document 1 Filed 06/07/23 Page 25 of 34

26

113. Again, DistroKid did not disclose the stores and streaming services that provided

DistroKid with the takedown.

114. DistroKid refused to provide this information to Doeman, and others similarly

situated. And, DistroKid withheld this information pursuant to its own internal policies. As the

email above stated, DistroKid handles takedowns by not disclosing the stores and platforms that

obtained the Takedown Request, and simply telling the artist to speak with the takedown party to

figure it out.

115. DistroKid’s internal policy regarding takedowns against ILIAs creates an

environment where an ILIA’s music can be taken down, but the ILIA is not given any

information or tools, other than the take-down party’s contact info, to have the music put back

online, especially where it’s a misuse of §512 such that the take-down party will not resolve the

issue in good faith.

Case 1:23-cv-04776-VEC Document 1 Filed 06/07/23 Page 26 of 34

27

116. Indeed, it gives the takedown party complete control over it.

117. DistroKid did not do an investigation into Doeman’s claims. Indeed, in an email

DistroKid told Doeman that it would forward his issues to a claims department. It never did so.

In fact it stopped responding to Doeman after he followed up several times.

VI. CLASS ACTION ALLEGATIONS

118. Plaintiff brings this action on behalf of itself, and a class action under the Federal

Rules of Civil Procedure, Rule 23(a), (b)(2) and (b)(3), seeking damages and injunctive relief

pursuant to New York state law on behalf of the members of the following class:

All persons who, on or after June 7, 2023, were or had been DistroKid accountholders who

have had non-infringing uses of expression distributed by DistroKid taken down from third-party

Platforms because of wrongful Takedown Notices sent to said Platforms.

119. Excluded from the Class are the Defendant and its officers, directors, management,

employees, subsidiaries, or affiliates; all governmental entities; and the judge to whom this case is

assigned, as well as the judge’s immediate family members, judicial officers and their personnel.

120. Numerosity: On information and belief, there are hundreds—if not thousands—of

DistroKid accountholders who have had non-infringing uses of expression taken down because of

wrongful Takedown Notices sent to Platforms. Given the likely existence of hundreds or thousands

of members of the alleged class, the alleged class is so numerous that joinder of all members is

impracticable. See Fed. R. Civ. P. 23(a)(1).

121. Typicality: Doeman’s claims are typical of those raised by the members of the class

because they stem from a form contract and actions by DistroKid in accordance with its policies

and procedures. Counsel are aware of no atypical defenses that would be eligible with respect to

DistroKid.

Case 1:23-cv-04776-VEC Document 1 Filed 06/07/23 Page 27 of 34

28

122. Adequate representation: Doeman will adequately and faithfully represent

interests of the class-members in maximizing the value of their individual damages claims and in

vigorously and zealously prosecuting their claims on important issues that strike at the heart of the

ability of ILIAs to get—and keep—their music online and from being abused.

123. Commonality: Common issues abound. Questions of law and fact common to the

members of the proposed Classes predominate over questions that may affect only individual

members of the Classes because Defendants have acted on grounds generally applicable to the

Classes and because Class members share a common injury. The common applicability of the

relevant facts to claims of Plaintiff and the proposed Classes are inherent in Defendants’ wrongful

conduct, because the New York state-law claims asserted by the alleged class stem from the

contractual relationship between DistroKid and its accountholders and because DistroKid uses a

form contract in managing relationships, all issues relating to the contract (formation, duties,

interpretation, etc.) are common to the class. Moreover, because the claims also stem from

DistroKid’s actions in accordance with its policies and procedures, DistroKid’s response to notice-

and-takedowns and refusal to conduct investigation, refusal to identify materials, there exist

questions of law and fact common to the class. See Fed. R. Civ. P. 23(a)(2).

124. There are common questions of law and fact specific to the Class that predominate

over any questions affecting individual members.

125. Prevention of Inconsistent or varying adjudications: If individuals filed their own

suit for the conduct complained of, there will likely be inconsistent and widely carrying results.

126. Injunctive relief: By way of its conduct described in this complaint, Defendant has

acted on grounds that apply generally to the proposed Class. Accordingly, injunctive relief is

appropriate and would benefit the Class as a whole.

Case 1:23-cv-04776-VEC Document 1 Filed 06/07/23 Page 28 of 34

29

127. Predominance and superiority: The issues common to the class predominate and

appear to be determinative of liability. Class proceedings on these facts and this law are superior

to all other available methods for the fair and efficient adjudication of this controversy, given that

joinder of all members is impracticable. Even if members of the proposed Class could sustain

individual litigation, that course would not be preferable to a class action because individual

litigation would increase the delay and expense to the parties due to the complex factual and legal

controversies present in this matter. Here, the class action device will present far fewer

management difficulties, and it will provide the benefit of a single adjudication, economies of

scale, and comprehensive supervision by this Court. Further, uniformity of decisions will be

ensured.

Case 1:23-cv-04776-VEC Document 1 Filed 06/07/23 Page 29 of 34

30

VII. CAUSES OF ACTION

FIRST CAUSE OF ACTION

COMMON-LAW BREACH OF FIDUCIARY DUTY

against DistroKid and asserted as a class action

128. Plaintiff Doeman hereby reasserts and realleges all paragraphs alleged above.

129. A Fiduciary Duty Existed. DistroKid acts on behalf of Doeman and other ILIAs.

DistroKid negotiates the terms of uploading music with the Platforms. DistroKid collects ILIAs’

money. DistroKid pays the ILIAs their money. ILIAs are dependent upon and required to use

third-party distribution companies to upload music to many of the most popular streaming services

like Spotify and Apple Music. Without such distributors, their music will not be populated to those

platforms.

130. On behalf of Plaintiff and others similarly situated, DistroKid negotiates the terms

and procedures of uploading and taking music down with the streaming services. Plaintiff and

others similarly situated do not have any insight into, or control over what those negotiated terms

are. DistroKid negotiates with the streaming platforms, uploads music to the streaming platforms,

and collects royalties on behalf of Plaintiff and others similarly situated, putting it in a position of

control and comprehensive knowledge of the system- something that Plaintiff and others similarly

situated are not. DistroKid advises Plaintiff and others similarly situated on its ecosystem that it

controls and has superior knowledge of. For example, DistroKid advises Plaintiff and others

similarly situated on how to upload their music, on what the terms and procedures are for

uploading, the royalty collection process, etc.

131. Misconduct by DistroKid. Despite having information available to it, DistroKid

did not provide Doeman with all of the information that it had about the takedown notice.

DistroKid did not provide the proper information to submit a counter-notice. And, it did not initiate

Case 1:23-cv-04776-VEC Document 1 Filed 06/07/23 Page 30 of 34

31

a reasonable investigation when the take-down notice was challenged by the copyright owner, i.e.,

Doeman.

132. Damages Directly Caused by DistroKid’s Misconduct. By removing Plaintiff’s

music from the streaming services, Doeman lost revenue from the potential streams from current

listeners and new listeners. Further, Doeman’s song lost potential revenue from live shows,

merchandise, and other related revenue streams from his song gaining popularity on streaming

services.

133. CLAIM 1: DistroKid breached its fiduciary duty to Doeman and others similarly

situated.

SECOND CAUSE OF ACTION

COMMON-LAW BREACH OF THE IMPLIED COVENANT

OF GOOD FAITH AND FAIR DEALING

against DistroKid and asserted as a class action

134. Plaintiff Doeman hereby reasserts and realleges all paragraphs alleged above.

135. Contract Formation. Doeman and DistroKid entered into a legally binding

contract under New York law.

136. Implied Covenant of Good Faith and Fair Dealing. The covenant of good faith

and fair dealing is implied by law and is not waivable.

137. Breach of Implied Covenant. DistroKid breached the covenant of good faith and

fair dealing when it refused to provide the information regarding the takedown (especially the

information necessary for Doeman to get the music put back up whether via DistroKid or other

music distributors) and refused to conduct a reasonable investigation regarding attempts to keep

the music up.

138. Causation and Damages. By removing Plaintiff’s music from the streaming

services, Doeman lost revenue from the potential streams from current listeners and new listeners.

Case 1:23-cv-04776-VEC Document 1 Filed 06/07/23 Page 31 of 34

32

Further, Doeman’s song lost potential revenue from live shows, merchandise, and other related

revenue streams from his song gaining popularity on streaming services.

139. CLAIM 2: DistroKid breached its fiduciary duty to Doeman and others similarly

situated.

THIRD CAUSE OF ACTION

KNOWING AND MATERIAL MISREPRESENTATIONS

IN NOTICE-AND-TAKEDOWN REQUESTS

against Ms. George and asserted an individual basis only

140. Plaintiff Doeman hereby reasserts and realleges all paragraphs alleged above.

141. Any Person. Ms. George is a natural person subject to liability under 17 U.S.C.

§ 512(f) because this subsection of the DMCA makes subject to liability “[a]ny person” who

undertakes the acts of knowing and material misrepresentations under 17 U.S.C. § 512.

142. Material Misrepresentation. Ms. George sent a Takedown Request to various

streaming services in which she materially misrepresented that Doeman’s material—“Scary

Movie”—as posted there was infringing. It was not infringing. Thus, Ms. George’s Takedown

Request was a material misrepresentation. That’s because infringement requires unauthorized

exercise of the exclusive rights under Section 106. Yet, as discussed above, Doeman’s posting

was authorized by Doeman itself, by Mr. Wilson, and, in fact, even by Ms. George herself (until

she purported to withdraw her authorization but without legal effect because she is not the

copyright owner of “Scary Movie”). And, because the copyrights were owned by Doeman and/or

by Mr. Wilson, Ms. George had no right to restrict these owners’ use of the “Scary Movie” or

otherwise inhibit their use. Indeed, insofar as Doeman wrote, directed, masterminded, and

orchestrated the song, Doeman owned it in full. And, Doeman has not transferred its ownership

interest, certainly not to Ms. George. Thus, Ms. George’s Takedown Requests were material

misrepresentations under Section 512(c) regarding whether “Scary Movie” was infringing when

Case 1:23-cv-04776-VEC Document 1 Filed 06/07/23 Page 32 of 34

33

posted to the streaming service via DistroKid because the posting of “Scary Movie” was

authorized—indeed, conducted—by the copyright owner of “Scary Movie” itself.

143. Knowing Misrepresentation. Likewise, Ms. George’s Takedown Request

knowingly misrepresented that Doeman’s material—“Scary Movie”—was infringing. Ms. George

was and is well aware that Doeman and Mr. Wilson had the rights in “Scary Movie”—and she did

not care but rather acted out of personal animus and spite. Ms. George asked Mr. Wilson to remove

her name from the song.

144. CLAIM 3: Ms. George knowingly and materially mispresented under Section 512(c)

that material and/or activity is infringing.

VIII. PRAYER FOR RELIEF

WHEREFORE, Doeman prays for judgment in its favor and against Ms. George, and

further prays for judgment in its favor, and judgment in the favor of those similarly situated, against

DistroKid, seeking any and all relief permitted, including:

I. Money Damages, Costs, and Fees: That the Court, if permitted, money damages

a. Award Doeman damages as against DistroKid and Ms. George.

b. Award Doeman full recovery of costs as against DistroKid and Ms. George.

c. Award Doeman reasonable attorneys’ fees as against Ms. George.

II. Injunctive Relief: That the Court, if permitted and where necessary to provide a

remedy where money damages cannot adequately and sufficiently compensate Doeman:

a. Grant a preliminary and a permanent injunction preventing and restraining

Ms. George.

III. Other Relief: That the Court, if permitted,

a. Grant any other relief permitted by law.

Case 1:23-cv-04776-VEC Document 1 Filed 06/07/23 Page 33 of 34

34

IX. JURY DEMAND

145. Plaintiff Doeman, on behalf of itself and others similarly situated, hereby demands

a trial by jury of all issues so triable. See Fed. R. Civ. P. 39: U.S. Const. amend. VII.

Dated: June 7, 2023

Respectfully submitted,

Megan Keenan

Oregon State Bar No. 204657

P.O. Box 8684

Portland, OR 97207

Phone: (925) 330-0359

Megan@InformationDignityAlliance.org

Attorney for Plaintiff

Case 1:23-cv-04776-VEC Document 1 Filed 06/07/23 Page 34 of 34