K–12 Local Control

Funding

The State’s Approach Has Not Ensured That

Significant Funding Is Benefiting Students as

Intended to Close Achievement Gaps

November 2019

REPORT

For questions regarding the contents of this report, please contact MargaritaFernández, Chief of Public Affairs, at ..

This report is also available online at www.auditor.ca.gov | Alternative format reports available upon request | Permission is granted to reproduce reports

Capitol Mall, Suite | Sacramento | CA |

CALIFORNIA STATE AUDITOR

.. | TTY ..

...

For complaints of state employee misconduct,

contact us through the Whistleblower Hotline:

Don’t want to miss any of our reports? Subscribe to our email list at

auditor.ca.gov

Elaine M. Howle State Auditor

621 Capitol Mall, Suite 1200 | Sacramento, CA 95814 | 916.445.0255 | 916.327.0019 fax | www.auditor.ca.gov

November ,

2019‑ 101

e Governor of California

President pro Tempore of the Senate

Speaker of the Assembly

State Capitol

Sacramento, California

Dear Governor and Legislative Leaders:

As directed by the Joint Legislative Audit Committee, my office conducted an audit of the funding

that the State provides to school districts under the Local Control Funding Formula (LCFF). Our

assessment focused on state and district efforts to implement LCFF, and the following report details

the audit’s findings and conclusions. In general, we determined that theState’s approach to LCFF

has not ensured that funding is benefiting students as intended.

e State intended for LCFF to provide more local control over the spending of state K– funds

and to improve educational outcomes among certain student groups. Specifically, in addition to base

funding that districts can use for any local educational purpose, LCFF would also provide districts

with supplemental and concentration funds based on the proportions of students they serve who

are English learners, youth in foster care, and those from households with low incomes (intended

student groups).

We are concerned that the State does not explicitly require districts to spend their supplemental and

concentration funds on the intended student groups or to track how they spend those funds; therefore,

neither state nor local stakeholders have adequate information to assess the impact of those funds

on intended student groups. Further compounding the problem, the State adopted regulations that

deferred full implementation of the supplemental and concentration funding formulas as partof

the transition from the previous funding model to LCFF. Since fiscal year –, this deferral

offull formula implementation has caused the three districts we reviewed to identify approximately

. million as being part of its base funds rather than supplemental and concentration funds.

We also had difficulty determining the extent to which the districts used those funds to increase or

improve services for intended student groups because of unclear descriptions in their local control

and accountability plans.

e State has an opportunity to take steps toward learning more about the effectiveness of

billions ofdollars that it allocates for K– education. By collecting additional information about

districts’ uses of supplemental and concentration funds, the State could begin to determine

howdistricts’spending of those funds affects educational outcomes of intended student groups and

whether it needs to take further action to ensure that these students receive the services they need.

Respectfully submitted,

ELAINE M. HOWLE, CPA

California State Auditor

iv California State Auditor Report 2019-101

November 2019

Selected Abbreviations Used in This Report

CCSESA California County Superintendents Educational Services Association

CDE California Department of Education

Clovis Unified Clovis Unified School District

county offices county offices of education

LCFF Local Control Funding Formula

LCAP Local Control and Accountability Plan

Oakland Unified Oakland Unified School District

San Diego Unified San Diego Unified School District

State Board California State Board of Education

vCalifornia State Auditor Report 2019-101

November 2019

Contents

Summary 1

Introduction 5

Audit Results

California’s Approach to Overseeing Supplemental and

Concentration Funds Has Not Always Ensured That Those

Funds Benefit Intended Student Groups 15

LCAPs Have Not Consistently Provided Transparency or

Facilitated Accountability 24

The State Currently Lacks Information That Would Better

Enable It to Measure the Effectiveness of LCFF 29

Recommendations 38

Appendix A

Scope and Methodology 41

Appendix B

Trends of LCFF Funding 45

Response to the Audit

California State Board of Education 47

California State Auditor’s Comments on theResponse From

the California State Board of Education 57

vi California State Auditor Report 2019-101

November 2019

Blank page inserted for reproduction purposes only.

1California State Auditor Report 2019-101

November 2019

Summary

Results in Brief

Since fiscal year –, California has funded K– education

in part through an approach called the Local Control Funding

Formula (LCFF). e State intended for LCFF to provide more

local control over the spending of state funding and to improve

educational outcomes among certain student groups. rough

LCFF, the State envisioned providing billions of dollars each year

to local educational agencies—with most of those funds going to

school districts—in part based on their student populations of

English learners, youth in foster care, and those from households

with low incomes (intended student groups). Specifically, in

addition to a base funding amount that they can use for any local

educational purpose, districts would also receive supplemental

and concentration funds based on the proportions of intended

students they serve. e State established these supplemental and

concentration funds in recognition of the fact that districts may

require different levels of funding to provide adequate services for

the students they educate. However, the State’s approach to LCFF

places oversight responsibilities for supplemental and concentration

funds almost entirely on local entities, such as county offices of

education and local stakeholders. is approach has not always

ensured that these funds benefit the intended student groups.

We are particularly concerned that the State does not explicitly

require districts to spend their supplemental and concentration

funds on the intended student groups or to track their spending

of those funds. Without a means of tracking how districts use

supplemental and concentration funds, state and local policymakers

and other local stakeholders lack adequate information to assess

the impact of those funds on the outcomes of intended student

groups. Although regulations adopted to implement LCFF require

districts to use these funds to increase or improve services for

intended student groups, the regulations do not create an effective

means of ensuring that districts do so. Districts must identify in

their annual local control and accountability plans (LCAPs) the

supplemental and concentration funds they expect to receive and

spend. LCAPs provide a key opportunity for stakeholders to ensure

that districts direct the funds toward the intended student groups.

However, districts can treat any supplemental and concentration

funds that they do not fully spend in a given year as base funds in

the following year, meaning that the districts can use the funds

for general purposes that do not directly serve intended student

groups. Despite this lack of restriction, the State has not established

Audit Highlights . . .

Our audit of the funding that the State

provides to school districts under the LCFF

revealed the following:

» The State’s approach to LCFF has not

ensured that funding is benefiting

intended student groups and closing

achievement gaps.

» The State does not explicitly require

districts to spend their supplemental

and concentration funds on the intended

student groups or to track their spending

of those funds.

• Districts can treat any unspent

supplemental and concentration funds

in a given year as base funds in the

following year and can use those funds

for general purposes.

» Since fiscal year 2013–14, the deferral

of full formula implementation to

LCFF has caused the three districts we

reviewed to identify $320 million as

being part of their base funds rather than

supplemental and concentration funds.

» Districts do not always include clear

information in their LCAPs regarding

their use of supplemental and

concentration funds.

» Policymakers and stakeholders lack

adequate information to assess

the impact of supplemental and

concentration funds on the educational

outcomes of the intended student groups.

California State Auditor Report 2019-101

November 2019

2

a process for districts to track supplemental and concentration

funds that remain unspent at the end of the year and to ensure that

they spend those funds appropriately.

Our review of three large districts suggests that the State’s approach

for determining supplemental and concentration funds has led

districts to identify hundreds of millions of dollars of LCFF funding

as base funds rather than supplemental and concentration funds

since it implemented LCFF in fiscal year –. For the transition

from its previous funding model to LCFF, the State adopted

regulations that required districts to estimate their supplemental

and concentration funds based on prior-year spending, rather

than on the supplemental and concentration funding formulas

described in state law, which are based on districts percentages of

intended student groups. is approach essentially deferred full

implementation of these formulas. It also resulted in a difference

of approximately . million that the three districts identified

as base funds, rather than supplemental and concentration funds

for fiscal years – through –. In other words, by

directing districts to base their estimates on prior-year spending,

they identified amounts of supplemental and concentration funds

that were similar to amounts they had already been providing

before LCFF. If all districts statewide estimated at similar rates,

we believe that the regulations have likely led districts to identify

billions of dollars of LCFF funding as base rather than supplemental

and concentration funds since the inception of LCFF in fiscal

year –. By deferring the full implementation, the State also

likely deferred improved educational outcomes for the intended

studentgroups.

Moreover, even when districts did report supplemental and

concentration funds in their LCAPs, we had difficulty determining

whether or how the districts’ use of those funds increased or

improved services for intended student groups—a difficulty

that stakeholders likely share. One challenge is that the current

requirement districts must meet for spending supplemental

and concentration funds to benefit intended student groups is

essentially meaningless. Specifically, a district must describe in its

LCAP how it will increase or improve services for those students in

proportion to the amount of supplemental and concentration funds

it receives. However, it is unclear how a district would demonstrate

that it increased or improved services by a proportion, and neither

county offices of education nor the California Department of

Education are responsible for verifying whether districts actually

met the required proportional increases. Another problem is that

the legal requirements for county offices of education to approve

districts’ LCAPs, such as ensuring that they adhere to the State’s

LCAP template, are insufficient to ensure that those LCAPs are

clear and effective. When districts fail to clearly demonstrate

3California State Auditor Report 2019-101

November 2019

how they use supplemental and concentration funds to benefit

intended student groups, it not only reduces transparency but also

puts the districts at risk of stakeholders’ submitting complaints or

filinglawsuits.

Although the State intended LCFF to improve the educational

outcomes of the intended student groups, measuring the

effectiveness of LCFF with any precision remains difficult. e

California School Dashboard (dashboard) displays on a website

results for performance indicators across several student subgroups

and is one of the State’s accountability tools for LCFF. However,

it includes only two years of results so far, and . More

significantly, the State has not required districts to track and report

their expenditures of supplemental and concentration funds in

a way that aligns with the dashboard indicators, so determining

whether a particular district’s use of those funds is effectively

improving the performance of the intended student groups it

serves is challenging. Further, although districts must report in

their LCAPs information about the services on which they have

spent their supplemental and concentration funds, they often do

not effectively analyze whether those services have been successful.

As a result, stakeholders may struggle to hold districts accountable

for continuing to fund effective services and discontinuing

ineffectiveservices.

e State now has an opportunity to take an important step toward

learning more about the effectiveness of billions of dollars that it

allocates for K– education. We acknowledge that local control

is a key principle of LCFF, and we do not advocate undermining

that principle. However, implementation of a statewide tracking

mechanism for supplemental and concentration funds could

provide information to assess the impact of those funds on the

educational outcomes of intended student groups. For instance,

such a mechanism would provide assurance that districts spend

all of their supplemental and concentration funds for their

intended purpose. In addition, it would enable the State and

other stakeholders to better evaluate the effectiveness of districts’

spending strategies and the effectiveness of LCFF generally. By

collecting and reporting additional information about districts’ uses

of supplemental and concentration funds, the State could begin to

determine how districts’ spending of those funds affects students

and whether it needs to take further action to ensure that these

students receive the services they need.

California State Auditor Report 2019-101

November 2019

4

Selected Recommendations

To ensure that intended student groups receive the maximum

benefit from supplemental and concentration funds, the Legislature

should take the following actions:

• Amend state law to require districts and other local educational

agencies to identify any unspent supplemental and concentration

funds by annually reconciling the estimated amounts of

thesefunds they include in their LCAPs with the actual amounts

of funding the State reports apportioning to them.

• Amend state law to specify that unspent supplemental and

concentration funds at year-end must retain their designation

to increase and improve services for intended student

groupsandbe spent in a following year, and it should require

districts and other local educational agencies to identify in their

LCAPs the total amounts of any unspent supplemental and

concentration funds from the previous year.

To provide additional data for the State and other stakeholders

and to align spending information with the dashboard indicators

or other student outcomes, the Legislature should take the

followingactions:

• Require the State to direct districts and other local educational

agencies to track and report to it the total amount of

supplemental and concentration funds they receive and spend

each year.

• Require the State to identify a common method that districts

and other local educational agencies must use to report the

types of services on which they spend their supplemental and

concentration funds.

Agency Comment

e State Board agreed with three of the four recommendations we

made to it.

5California State Auditor Report 2019-101

November 2019

Introduction

Background

e quality of California’s public education system directly affects

the lives of many of the State’s residents. About million students

in the K– grade levels attend public school in California. Since

fiscal year –, California has funded K– education in part

through an approach called the Local Control Funding Formula

(LCFF).

1

rough LCFF, the State provides billions of dollars each

year to local educational agencies: county offices of education

(county offices), school districts, and charter schools. School

districts receive most of those funds. For instance, districts received

nearly percent of the more than billion that the California

Department of Education (CDE) apportioned through LCFF in

fiscal year –. About billion of this billion consisted

of supplemental and concentration funds that CDE apportioned

to districts based on their student populations of English learners,

youth in foster care, and those from households with low incomes.

(intended student groups).

e State’s policy—consistent with its constitutional obligation—is

to afford all students in public schools equal access to educational

opportunity. e State intended these supplemental and

concentration funds—and LCFF generally—to establish more

equitable funding by recognizing that districts may require different

levels of funding to provide adequate services for the students they

educate. Nonetheless, state data demonstrate that certain student

groups have poorer educational outcomes, including academic and

other performance outcomes, in comparison to students overall

(achievement gaps). ese achievement gaps have likely contributed

to California’s consistently ranking below the national average

on metrics such as National Assessment of Educational Progress

reading and mathematics scores. One of the goals of LCFF is to

address achievement gaps among intended student groups, and

research indicates that intended student groups frequently need

additional services and other support to be successful in school.

For this audit, we selected three large districts to review—Clovis

Unified School District (Clovis Unified), Oakland Unified School

District (Oakland Unified), and San Diego Unified School District

(San Diego Unified). We examined whether these districts have

used supplemental and concentration funds to provide services

to the intended student groups and whether those services have

improved the intended student groups’ educational outcomes.

1

Local educational agencies may also receive other types of state and federal funding, including

special education funding and Every Student Succeeds Act Title funding.

California State Auditor Report 2019-101

November 2019

6

California Funds K–12 Education Primarily Through LCFF

e State made an historic shift in the way it funds K– education

when it implemented LCFF more than six years ago. LCFF was

intended to simplify the State’s funding model and provide school

districts with more local control over how they spend the state

funding they receive. Before LCFF, districts received a certain amount

of funding for each student, known as general‑purpose funding

or revenue limit funding. ey also received additional funding—

commonly called categorical funds—that the State designated

for specific purposes, such as serving special education students

or reducing class sizes. Districts considered the restrictions and

administrative requirements associated with categorical funds to be

burdensome. At one time, the State had more than categorically

funded programs, many of which had different spending and

eligibilityrequirements.

In contrast, LCFF has three primary funding components: base funds,

supplemental funds, and concentration funds. State law establishes

base funding rates by grade span, such as kindergarten through

thirdgrade, and requires CDE to compute each district’s base fund

amount by multiplying those rates by the district’s average daily student

attendance. Depending on its percentage of students in the intended

student groups, a district can receive an additional percent of the

set base rate as supplemental funds. When more than percent of a

district’s students are in the intended student groups, the district would

also receive as concentration funds an additional percent of the base

rate for its percentage of students above this threshold. Figure details

LCFF’s funding components. Unlike categorical funds, LCFF funding

is generally unrestricted, meaning that districts can use it for any local

educational purpose not prohibited by law. However, districts must

use supplemental and concentration funds to increase or improve

services for intended student groups in proportion to the amount of

supplemental and concentration funds they receive.

Although the Legislature implemented LCFF in fiscal year –,

it did not fully fund it until fiscal year – because LCFF

represented a significant increase in the amount of educational

funding the State was providing. Consequently, the funding formulas

for base, supplemental, and concentration funds in state law

represented a “target” funding amount, not the amounts that districts

actually received. Instead, during this phase-in period, the State

implemented a transition entitlement. is entitlement consisted of

a funding floor amount and a transition adjustment amount known

as gap funding. However, it did not separately identify the portions

of the transition entitlements that were base, supplemental, and

concentration funds. e funding floor consisted of a district’s fiscal

year – revenue limit funding, divided by its fiscal year –

average daily attendance, and then multiplied by its current-year

7California State Auditor Report 2019-101

November 2019

average daily attendance. e State based the amount of gap funding

a district received each year from fiscal year – through –

on the amount of funding provided in the annual Budget Act to

incrementally reduce over time the gap between districts’ funding

floors and the target amounts they would receive when the LCFF

became fully funded.

Figure 1

CDE Calculates Target Supplemental and Concentration Funds for Districts Based on Their Populations of Intended

Student Groups

A district has 100 students

Of those 100 students, 75 of them are in intended student groups (75

%

)

The base amount is $500 per student

100 students

$

500

$50,000

BASE FUNDS

SUPPLEMENTAL FUNDS

CONCENTRATION FUNDS

HYPOTHETICAL

EXAMPLE

A district’s base funding is

determined by its students’ average

daily attendance and grade level.

A district receives an extra 20 percent

of the base funding rate for its

percentage of intended students.

When the intended student groups exceed

55 percent of a district’s total enrollment, it

receives an additional 50 percent of the base

funding rate for its percentage of intended

students above the 55 percent threshold.

BASE FUNDS SUPPLEMENTAL FUNDS CONCENTRATION FUNDS

x

+

$50,000

20

%

75

%

$7,500

$50,000

50

%

(

75

% –

55

%

)

$5,000

x

x

x

x

$62,500

Total

LCFF Funding

$50,000

$7,500

$5,000

Source: Analysis of state law.

From fiscal years – through –, CDE calculated the target

amounts and transition entitlements for each district and reported the

funding amounts on its website multiple times throughout each year—

updating the amounts as it received additional attendanceinformation.

8 California State Auditor Report 2019-101

November 2019

However, although CDE reported base, supplemental,

and concentration proportions of the target amount,

the transition entitlement that districts actually

received did not separately identify these proportions.

Consequently, districts estimated the amounts of

LCFF funding they expected to receive and the

amounts of supplemental and concentration funds to

establish the proportion by which they must increase

or improve services for intended student groups. e

State Board of Education (State Board) adopted

regulations in instructing districts to estimate

their supplemental and concentration funds based

primarily on prior-year spending levels during the

phase-in period. After the end of each year, CDE

reported the total annual funding it had apportioned

to each district. e text box summarizes the basis for

determining supplemental and concentration funds

since LCFF was implemented in fiscal year–.

e three districts we selected to review receive different amounts of

LCFF funding. Figure presents information about the districts’

student populations and identifies the fiscal year – LCFF

funding that the districts had received as of June . Of the three,

Oakland Unified has the highest proportion of students in the

intended student groups and received the highest

proportion of supplemental and concentration

funds. Clovis Unified has the lowest proportion of

students in the intended student groups and

received supplemental funds but no

concentrationfunds.

The State Established Local Control and

Accountability Plans to Enhance Transparency

andAccountability for LCFF Funding

To enhance transparency and accountability for

LCFF funding, state law requires each school district

to develop and update annually—by July —a local

control and accountability plan (LCAP). e LCAP

is a three-year spending plan that describes the

district’s annual goals, services, and expenditures to

support positive student outcomes and to address

state and local priorities. In its LCAP, the district

describes its goals and the particular services

it plans to provide to meet those goals. When

developing its LCAP, each district must adhere to

a template that the State Board approves. As the

textbox describes, the LCAP template primarily

Before Full Implementation of LCFF, Supplemental

and Concentration Funds Were Not Based on

Percentages of Intended Student Groups

FISCAL

YEARS

BASIS FOR DETERMINING

SUPPLEMENTAL AND

CONCENTRATION FUNDS

LCFF Transition

Period

2013–14

through

2018–19

Primarily by prior year

spending amounts

LCFF Full

Implementation

2019–20

forward

Primarily by enrollment

percentages of intended

student groups

Source: Analysis of state law, CDE documents, and district

documents.

Five Primary Sections of the LCAP

• Summary: provides a brief overview of important

elements contained within the LCAP.

• Annual Update: captures the district’s progress toward the

expected outcomes for each goal from the prior year and

estimated actual expenditures.

• Stakeholder Engagement: describes the consultation

process the district had with parents, students, school

personnel, and the community, including how that

engagement contributed to the development of the LCAP.

• Goals, Actions, and Services: focuses on the goals, actions,

expenditures, and progress indicators that the district

hasidentified.

• Demonstration of Increased or Improved Services:

details the district’s use of supplemental and concentration

funds to meet the requirement to increase or improve

services proportionally to the increase in these funds.

This is the single section of the LCAP focused solely on

supplemental and concentration funds.

Source: LCAP template and CCSESA LCAP approval manual.

9California State Auditor Report 2019-101

November 2019

consists of fivesections. In addition to these five sections, the State

Board added to the – LCAP an addendum related to federal

education law and added to the – LCAP a brief, accessible

budget overview for parents that summarizes the LCAP’s important

elements. e State Board is currently considering additional

revisions to the – template.

Figure 2

Because of Differences in Their Student Populations, Our Selected Districts Received Varying Amounts of LCFF

Funding for Fiscal Year 2018–19

�342.6

MILLION

�29.9

MILLION

�0

�284.8

MILLION

�43.7

MILLION

�31.0

MILLION

�359.5 MILLION

�821.1

MILLION

�101.0

MILLION

�26.8

MILLION

�948.9 MILLION

�

25 MILLION

AVERAGE DAILY

ATTENDANCE

BASE FUNDS

SUPPLEMENTAL

FUNDS

CONCENTRATION

FUNDS

34,270

41,160

98,760

INTENDED

STUDENT GROUPS

77

%

44

%

62

%

Total LCFF

*

Clovis Unified

�372.5 MILLION

Oakland Unified

San Diego Unified

Source: CDE’s 2018–19 principal apportionment data.

* Total LCFF does not include add-on funding that districts received through the Targeted Instructional Improvement Block Grant program, the

Home-to-School Transportation program, and the Small School District Transportation program.

10 California State Auditor Report 2019-101

November 2019

In the last section of the LCAP, each district must identify and report

the amount of supplemental and concentration funds it has estimated

that it will receive for the year, and it must demonstrate how it plans

to meet expenditure requirements for these funds. As we described

previously, each district must use its supplemental and concentration

funds to increase or improve services for intended students groups in

proportion to the amount of supplemental and concentration funds

they receive. ese increases or improvements must be in proportion

to the amount of supplemental and concentration funds that the

district receives based on its population of intended student groups. For

example, if a district’s supplemental and concentration funds for fiscal

year – represent percent of its total LCFF funding, that district

must increase or improve services for its intended student groups

by percent compared to the services provided for the rest of its

students in that year. In the final section of the LCAP, each district must

explain how the services it is providing increase or improve services

for intended student groups. Although the three districts we reviewed

each allocated some portion of its supplemental and concentration

funds directly to schools to spend, they also planned to use the funds

for a significant number of districtwide services and programs, such as

reducing class sizes or providing school nurses, as we discuss later.

As Figure indicates, a number of different state and local entities are

involved in overseeing and making decisions related to LCFF funding.

For example, local stakeholders, such as parents, teachers, and other

interested groups, provide input and oversight to ensure that districts

develop clear and informative LCAPs. Stakeholders review and

provide comments on a district’s draft LCAP. In addition, they can

submit complaints to the district or county office, and appeal to CDE,

if they believe a district has violated state law in completing its LCAP.

In most instances, county offices are responsible

for approving LCAPs for the districts within their

counties.

2

Figure depicts the LCAP development

and approval process. e California County

Superintendents Educational Services Association

(CCSESA) has developed an LCAP approval manual

that county offices can use as a guide during their

reviews. A county office must approve a district’s

LCAP if the LCAP meets the conditions listed in the

text box. If a county office rejects a district’s LCAP, it

must provide assistance to that district that focuses

on revising the LCAP so that the county office can

approve it before October of that year. is date is

the deadline for county offices to approve LCAPs.

2

The exception is when a county has jurisdiction over a single school district; in these circumstances,

CDE approves the district’s LCAP.

LCAP Approval Requirements for County Offices

The county office must approve a district’s LCAP on or

before October 8 if it determines all of the following aretrue:

• The district’s LCAP adheres to the LCAP template.

• The district’s budget includes expenditures sufficient to

implement the services included in the LCAP.

• The district’s LCAP adheres to the expenditure

requirements for supplemental and concentration funds.

Source: State law.

11California State Auditor Report 2019-101

November 2019

Figure 3

LCFF Relies on Local Decision Making and Oversight

58 County Offices

County offices approve districts’ LCAPs and

ensure that the LCAPs adhere to spending

requirements for supplemental and

concentration funds.

Approximately 1,000 Districts

Districts decide how to spend

supplemental and concentration

funds and explain their decisions in

their LCAPs.

Approximately 10,000 School Sites

School sites receive and spend some of

the districts’ supplemental and

concentration funds.

COUNTIES

STATE

DISTRICTS

STAKEHOLDERS

SCHOOLS

The State Board is California’s K-12 policy-making

body that adopts regulations and the LCAP template.

CDE collects and reports certain data from county offices

and districts, manages the dashboard, provides

guidance to county offices and districts, and issues

reports as part of the uniform complaint process.

Districts must consult with stakeholders, including parents and

teachers, in developing their LCAPs. They must hold public

meetings to solicit recommendations from members of the

public regarding the services and expenditures in their LCAPs.

CCESA developed an LCAP approval

manual, which county offices can use as

guidance when approving LCAPs.

STATE BOARD

CDE

Key oversight entity for districts’

spending of supplemental and

concentration funds

37+15=

24+15=

=87

10=99

Source: Analysis of state law, CDE documents, and the CCSESA LCAP Approval Manual.

12 California State Auditor Report 2019-101

November 2019

Figure 4

LCAP Development and Approval Is an Ongoing Process

APRIL • MAY

FEBRUARY • MARCH

AUGUST • SEPTEMBER

JUNE • JULY

OCTOBER • NOVEMBERDECEMBER • JANUARYOCTOBER • NOVEMBER

The school year begins

generally in August.

County offices and local stakeholders, such as parents, are the main safeguards that exist to ensure that

districts develop clear and informative LCAPs. Thus, the quality of the county offices’ review and the

quality of stakeholder engagement can have a significant impact on the LCAPs.

(Usually in December)

CDE releases the California

School Dashboard.

Districts begin developing their LCAPs for the upcoming school year,

and engage stakeholders to gather input and feedback for the LCAP.

OCTOBER 8*

Final day that county

offices may approve LCAPs.

County offices conduct LCAP trainings for district staff.

County offices conduct

preliminary reviews of

districts’ LCAPs.

STATE

DISTRICTS

COUNTY OFFICES

Districts work with their county

office to address concerns

related to their LCAPs.

County offices conduct

formal LCAP reviews.

JULY 1

Final day that districts may

submit their LCAPs to the county.

Source: Analysis of state laws, CCSESA manual, and other documents.

* Though LCAP approval is required by October 8, the recommended approval date is September 15 to coincide with budget approval timelines. If a district’s LCAP is not approved by September 15,

aconditional budget approval may be an option, where appropriate.

13California State Auditor Report 2019-101

November 2019

The California School Dashboard and Statewide System of Support

Are the Core of the State’s Accountability System

e State measures how well schools and districts are meeting the

needs of all students through the California School Dashboard

(dashboard). In conjunction with LCFF, state law

requires the State to develop and maintain an

evaluation tool for publicly reporting performance

data for specified student groups. To meet this

requirement and to provide transparency and

accountability, the State introduced the dashboard

in March . e dashboard presents student

performance information at both thedistrict level

and the school-site level. As the textbox shows,

the dashboard displays the results for sevencore

performance indicators across a number of

student subgroups, including the threeintended

student groups. e dashboard generally uses data

that districts submit to CDE. CDE has released

twoyears of results, for and.

A primary function of the dashboard, in addition to

publishing performance data, is to identify districts

that are failing to close achievement gaps and

need additional county or state assistance through

the statewide system of support. e State Board

adopted this system in . As Figure shows, the

system provides threelevels of support: voluntary

technical assistance, differentiated assistance, and

intensive intervention. Because districts choose

to seek technical assistance and CDE’s intensive

intervention is for districts that demonstrate

persistent performance issues over a number

of years, the State currently uses differentiated

assistance as its primary process for ensuring that

districts receive individualized assistance to close

achievement gaps.

A county office must offer differentiated assistance

to a school district if any student group within

that district does not meet performance standards

for two or more performance indicators on

the dashboard. According to data from the

dashboard, more than percent of school

districts statewide were eligible for differentiated

assistance for at least one student group, which

indicates that significant achievement gaps persist

throughout theState.

Dashboard Indicators and Student Groups

State Indicators*

English Language Arts: Based on state testing results

for English language arts (Smarter Balanced Summative

Assessment) for grades three through eight and grade 11.

Mathematics: Based on state testing results for

mathematics (Smarter Balanced Summative Assessment)

for grades three through eight and grade 11.

English Learner Progress: Based on results from the

English Language Proficiency Assessments for California.

College/Career: Based on various measures that evaluate

preparedness for college or career, such as career

technical education pathway completion, A‑G course

completion, and Advanced Placement exams.

Graduation Rate: Based on the number of students who

earn a high school diploma within four years of entering

ninth grade.

Chronic Absenteeism: Based on the number of students

in kindergarten through grade eight who were absent

at least 10 percent or more of the instructional days that

they were enrolled to attend a school.

Suspension Rate: Based on the number of students who

were suspended at least once during the school year.

Student Groups

Intended student groups for supplemental and

concentration funds:

English Learners, Youth in Foster Care, Students from

Households with Low Incomes.

Other student groups: Students Experiencing

Homelessness, Students With Disabilities, African

American, American Indian, Asian, Filipino, Hispanic,

Pacific Islander, White, and Two or MoreRaces.

Source: Analysis of the 2018 dashboard and the 2018 California

School Dashboard Technical Guide.

* The dashboard also reports measures of progress on local

indicators for individual local educational agencies based on

information that they collect locally, such as appropriately

assigned teachers, parent engagement, and school climate.

14 California State Auditor Report 2019-101

November 2019

Figure 5

Differentiated Assistance Is the State’s Primary Process for Addressing Achievement Gaps

Voluntary Technical Assistance

LEVEL 1

State and local agencies provide support

resources and tools that districts may use

to improve student performance.

Differentiated Assistance

LEVEL 2

California’s System of Suppport

County offices* provide individually

designed assistance for districts to address

performance issues, including achievement

gaps among student groups.

Intensive Intervention

LEVEL 3

The state superintendent of public instruction

may require further interventions for districts

with persistent performance issues that do

not improve over a specified time period.

CDE implemented this level in 2019.

CDE releases the dashboard.

County offices identify which districts have

achievement gaps that require differentiated

assistance. A county office must offer

differentiated assistance to a district if any

student group has dashboard indicators at red or

not met for two or more LCFF priorities.

County offices work with these districts to review

dashboard and other local data to determine strengths

and weaknesses and to identify how and why

subgroups are underperforming.

With guidance from county offices,

districts identify effective, evidence-based

programs and practices that will address

their areas of weakness.

County offices send districts a final letter

summarizing the identified programs and

practices.

Districts incorporate into their LCAPs

programs and practices they identified with

their county offices.

December

The following summer and following school year

Toward the end of the school year

1

3

2

4

5

6

Source: Analysis of state law and CDE documents.

* CDE provides differentiated assistance for county-run schools such as juvenile court schools.

15California State Auditor Report 2019-101

November 2019

Audit Results

California’s Approach to Overseeing Supplemental and Concentration

Funds Has Not Always Ensured That Those Funds Benefit Intended

Student Groups

e State’s implementation of LCFF has not yet proven effective at

increasing transparency and accountability for the supplemental and

concentration funds that CDE allocates to districts. Specifically, state

law does not explicitly require districts to use unspent supplemental

and concentration funds in the following year to benefit intended

student groups, nor does it require that they track their spending of

these funds. Furthermore, existing state law has allowed the districts

we reviewed to identify hundreds of millions of dollars in LCFF

funding as base rather than supplemental and concentration funds

during the phase-in period. If the Legislature intends for districts

touse all of the supplemental and concentration funds it allocates to

them to specifically increase or improve services for intended student

groups, it should amend state law to establish this requirement.

Additionally, districts do not always include clear information in their

LCAPs regarding their use of supplemental and concentration funds,

even though LCAPs are a key accountability tool for ensuring that

they budget and spend these funds to increase and improve services

for the intended student groups. e LCAPs’ lack of clarity has

reduced transparency and resulted in some stakeholders submitting

formal complaints and filing lawsuits in court. Until the State ensures

that districts spend all supplemental and concentration funds to

benefit the intended student groups, and that they provide clear,

accessible information regarding that spending in their LCAPs, the

intended student groups may not receive the services necessary to

close the State’s persistent achievement gaps.

The State Has Not Ensured That Districts Spend Supplemental and

Concentration Funds on Services for Intended Student Groups

As we discuss in the Introduction, the State instituted LCFF to

provide districts with supplemental and concentration funds

toimprove the educational outcomes of the intended student groups

and to increase transparency and accountability related to education

funding. However, LCFF has not yet successfully accomplished

these goals. As we discuss later, available data show improvements

in some student outcome measures since the State implemented

LCFF, although achievement gaps persist. In acknowledgment of

the fact that educating the intended student groups is more costly,

the State apportions the additional funds to districts based on their

intended student group populations; as a result, we would have

expected districts to track their spending of these funds. Instead,

a series of impediments hinders stakeholders’ ability to determine

California State Auditor Report 2019-101

November 2019

16

with assurance the amount of supplemental and concentration funds

that districts actually spend for the benefit of the intended student

groups, even though these are the students for whom they receive the

additional funding.

Most significantly, the current requirement districts must meet

when spending supplemental and concentration funds is essentially

meaningless. State law does not explicitly require that districts spend

all their supplemental and concentration funds for intended student

groups; instead, it states that they must use the funds toincrease or

improve services for those students in proportion to theamount of

supplemental and concentration funds they receive. For example,

in its fiscal year – LCAP, Clovis Unified calculated that its

supplemental funds represented an increase of . percent over its

LCFF base funds. Consequently, state law requires Clovis Unified

to increase or improve services for intended student groups by

.percent as compared to all students. However, it is unclear how

a district would demonstrate that it increased or improved services

by a specific percentage. In fact, two of the three districts we visited

stated that measuring objectively whether they have increased or

improved services by a specific percentage for any one student group

in comparison to all students is difficult. Furthermore, neither the

county offices nor CDE is responsible for verifying that districts have

achieved the required proportional increases.

In other words, state law created a mechanism to give additional

funds to districts that have higher proportions of intended student

groups, but it did not explicitly require or provide a means of ensuring

that those districts actually spent their additional funds on the specific

student groups for whom they were allocated. When we discussed this

lack of an explicit requirement with the State Board’s deputy policy

director and assistant counsel, he stated that he believes state law

reflects a recognition that investing to improve the overall education

program at a school site or within a district can be an effective way

to meet the needs of intended student groups. He added that tying a

legal obligation to dollar-to-dollar increases in expenditures would

discourage districts from implementing approaches that would

improve core programs in ways that better meet the needs of intended

students. Although we do not disagree with this premise, LCFF’s

intent and CDE’s own regulations make clear that supplemental and

concentration funds are fundamentally different from base funds—

districts must use them to increase or improve services for intended

student groups.

e second impediment to ensuring that districts use supplemental

and concentration funds for the intended student groups is that

the State does not require districts to track how they spend these

funds. Of the three districts we reviewed, only Clovis Unified

generally tracked its supplemental funds in its accounting system.

State law does not explicitly

require that districts spend all their

supplemental and concentration

funds for intended student groups.

17California State Auditor Report 2019-101

November 2019

e other twodistricts’ accounting systems tracked supplemental and

concentration funds inconsistently. At these districts, we struggled to

locate financial information to determine how much supplemental

and concentration funds they had received and if they had spent that

funding to benefit the intended student groups.

Furthermore, budget and expenditure information for supplemental

and concentration funds that districts include in their LCAPs is not

always transparent. Specifically, although the LCAP template requires

districts to include budgeted expenditures and estimates of actual

expenditures for each service they provide, it does not require them

to present summary-level expenditure information in a manner

that would allow stakeholders to compare districts’ total budgeted

expenditures to their total estimated actual expenditures without

significant effort. Consequently, the LCAPs for the three districts

we visited do not enable stakeholders to easily identify whether the

districts spent all of their supplemental and concentration funds as

planned. In fact, within their LCAPs, districts reported numerous

individual expenditures. Although the LCAP template asks districts

to explain “material differences” between the individual expenditure

amounts they budgeted and the estimated actual amounts they

spent, the template does not include a place for districts to report the

overall total differences between their budgeted and estimated actual

expenditures of supplemental and concentration funds.

State Law Deferred Full Implementation of Supplemental and

Concentration Funds, Resulting in Significantly Lower Amounts Than the

Funding Formulas Would Have Provided

Given the lack of clear information in the accounting systems and

LCAPs of the three districts we reviewed, we used the numerous

expenditures they reported in the LCAPs to manually sum the

amounts of supplemental and concentration funds they had budgeted

and spent. We had two key observations from our calculations of

these expenditures. First, we found that although the formulas in state

law for calculating supplemental and concentration funds are based

on a district’s proportions of intended student groups relative to its

total enrollment, the regulations that the State Board adopted for

local educational agencies to follow during the phase-in period do not

consider these proportions. As we explain in theIntroduction, before

the State fully funded LCFF in fiscal year–, the State adopted

regulations that required districts to annually estimate how much

base, supplemental, and concentration funds they expected to receive.

Districts then used these estimates to describe in their LCAPs the

services they planned to provide to intended student groups. Under

these regulations, districts were to base their estimates on prior-year

spending. Specifically, they were to base their estimates for fiscal

year – on the amounts they spent in fiscal year – on

Budget and expenditure

information for supplemental

and concentration funds that

districts include in their LCAPs is

notalwaystransparent.

California State Auditor Report 2019-101

November 2019

18

services for intended student groups, which must be greater than

or equal tothe amount of Economic Impact Aid they spent in fiscal

year–.

3

In subsequent years, the estimate was based on the

prior-year spending.

Because the regulations did not base the estimated amounts on

districts’ populations of intended student groups, the resulting

amounts of funding districts identified as supplemental and

concentration were significantly less than the amounts we

calculated using the proportions of intended student groups.

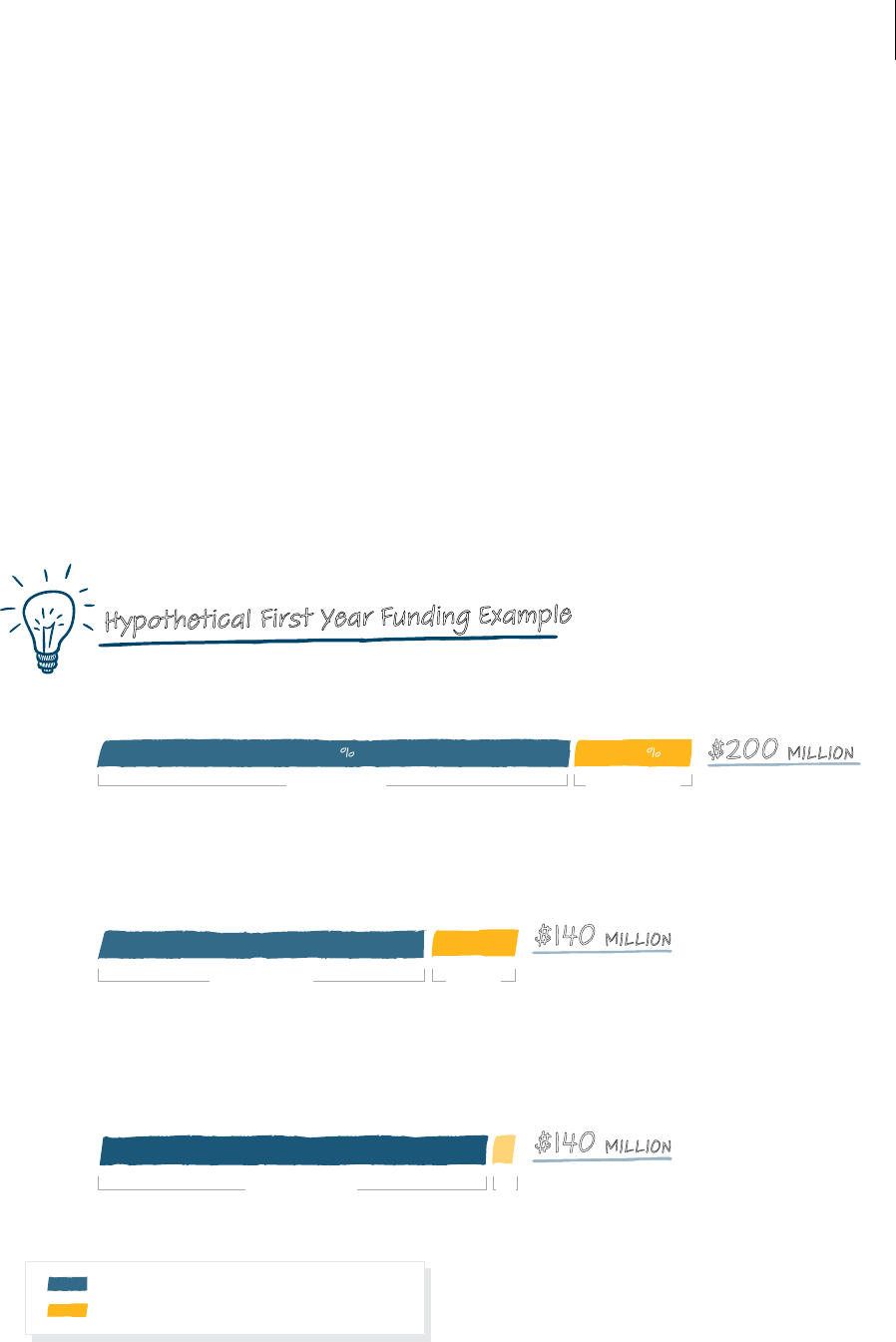

Figure presents a hypothetical example to illustrate the different

approaches for determining how much of the LCFF funding is

supplemental and concentration funds. When we applied the

same proportions of base, supplemental, and concentration funds

that exist in state law to the total LCFF funds the three districts

received, we identified significant amounts of supplemental and

concentration funds that districts otherwise would have included

in their LCAPs, as Figure demonstrates. In fact, since the State

implemented LCFF in fiscal year –, the regulations have led

the three districts to identify approximately . million of LCFF

funding as base rather than supplemental and concentration funds.

If all districts statewide estimated supplemental and concentration

funds at rates similar to those of the three districts we reviewed,

the difference between using the approach required by regulations

and basing their estimates on the proportions of intended student

groups would have amounted to billions of dollars since LCFF’s

implementation. According to State Board documents, because

districts had been using various funding sources to provide services

to intended student groups before the adoption of LCFF, the use of

prior-year spending allows a local educational agency to estimate

the actual services provided. In other words, by directing districts

to base their estimates on prior-year spending, districts identified

amounts of supplemental and concentration funds to increase or

improve services for intended student groups that were similar to

amounts they had already been providing before LCFF. erefore,

by deferring LCFF’s full implementation, the State likely also

deferred improvements in performance outcomes for intended

student groups.

Furthermore, the State has not established adequate accountability

controls over these funds. To ensure that districts estimated

accurately all the supplemental and concentration funds they

would receive, we expected that the State would have established a

process to validate the amounts districts identified when following

3

The Economic Impact Aid program was a state categorical program for kindergarten through

grade that provided additional English language acquisition programs, support and services

for students with limited English proficiency, and State Compensatory Education services for

educationally disadvantaged youth.

Since the State implemented LCFF in

fiscal year –, the regulations

have led the threedistricts

to identify approximately

.million of LCFF funding as

base rather than supplemental and

concentration funds.

19California State Auditor Report 2019-101

November 2019

theregulations. However, the State has not established such a

validation process. As a result, the districts’ estimations are the

only method for identifying the amount of supplemental and

concentration funds, and the amounts they included in their LCAPs

are the only source of information about how much of theLCFF

funding the State provided was treated as supplemental and

concentration. In Appendix B, we provide information about each

of the three districts’ LCFF funding for fiscal years – through

–.

Figure 6

Regulations Led to Different Proportions of Base, Supplemental, and Concentration Funds Than Full

Implementation of State Law Would HaveProvided

Target LCFF amount, based on state law related to

intended student groups.

Transition LCFF amount, applying the same proportions

of base, supplemental, and concentration funds.

Transition LCFF amount, based on prior year’s spending as required

by regulations adopted by the State Board.

Base Funds

Supplemental and Concentration Funds

80

%

20

%

95

%

5

%

80

20

$200 MILLION

$112 MILLION

$133 MILLION

$160 MILLION $40 MILLION

$140 MILLION

$140 MILLION

$7

MILLION

Hypothetical First Year Funding Example

$28

MILLION

Source: Analysis of state law, CDE documents, and district documents.

20 California State Auditor Report 2019-101

November 2019

Figure 7

State Regulations Resulted in Less Supplemental and Concentration Funds for the Three Selected Districts

Auditor-Calculated Supplemental and Concentration Funding Amounts Based on Funding Formula in State Law

Districts-Budgeted Supplemental and Concentration Funding Amounts in Accordance with California Regulations

0

50

100

150

200

$250

Dollars in Millions

2014–152013–14 2015–16

Fiscal Year

2016–17 2017–18 2018–19

33.1*

170.3

78.0*

193.0

165.6

218.0

211.3

224.9

222.5

227.2

234.7

232.5

$320.6 million difference

over five fiscal years.

Source: Analysis of state law, CDE’s principal apportionment data, and district LCAPs.

* When a district did not report the amount of supplemental and concentration funds it budgeted in its LCAP, we used the amount of expenditures it

reported, as we show in Appendix B.

e second key observation we identified in our analyses of the LCAPs

of the three districts we reviewed is that even when two of these districts

included supplemental and concentration funds in their LCAP budgets,

they often did not fully spend those funds during the year in question.

For example, in fiscal year –, San Diego Unified underspent by

percent, or . million, and Oakland Unified underspent by percent,

or million. is is problematic because we could find no requirement

under current law for districts to continue using unspent supplemental

and concentration funds in the following year to increase or improve

services for intended student groups—the unspent funds essentially can

be used for any purpose in subsequent years. Although the amounts in

question represent a small percentage of the two districts’ total LCFF

funding, they could have used the funding to provide additional resources

for intended student groups, such as English language support staff or

college counselors. Without direction from the State to do so, SanDiego

identified unspent supplemental and concentration funds from fiscal

year – and included that amount with the funding identified

in its – LCAP to provide services for intendedstudentgroups.

21California State Auditor Report 2019-101

November 2019

However, if districts statewide underspend their fiscal year –

supplemental and concentration funds by just percent each year,

they will not provide about million in services for the intended

studentgroups.

Determining whether or how districts used their unspent

supplemental and concentrations funds in the following year is difficult

because of their inconsistent tracking; however, in the absence of a

requirement to carry over unspent supplemental and concentration

funds for the same purposes, districts can spend them for general

purposes, not specifically for the direct support of intended student

groups. Two of the three county offices we visited acknowledged that

current law allows districts to potentially use unspent supplemental

and concentration funds for more generalpurposes.

Although state law requires county offices to review whether districts’

budget expenditures are sufficient to implement their planned LCAP

services, it does not require the county offices to examine whether

districts budget and spend all of their supplemental and

concentration funds and provides little guidance for their

review. To approve the financial portions of districts’

LCAPs, the three county offices we reviewed use the

CCSESA LCAP approval manual as a guide. e fiscal

year – manual includes guidelines for a

compliance-based review of expenditures that would

confirm, for example, that a district identified expenditure

amounts, sources, and budget references for each service.

e manual does not include steps that county offices

should take to ensure that districts budget and spend all

of their supplemental and concentration funds.

Consequently, the Fresno and San Diego county offices

did not compare districts’ budgeted expenditures with

their estimated actual expenditures to identify potential

underspending. Ultimately, the financial reviews county

offices are required to perform appear to be a compliance

exercise rather than a critical analysis of the expenditures.

Districts Do Not Always Clearly Describe in Their LCAPs How

the Supplemental and Concentration Funds They Spend

Districtwide Principally Benefit Intended Students

Districts may spend supplemental and concentration

funds for districtwide purposes by upgrading the entire

educational program, thereby benefiting more than just

intended student groups. However, districts can spend

districtwide only if they follow the requirements we list

in the text box. Given these requirements, we would

expect districts to sufficiently describe in their LCAPs

Requirements for Spending Supplemental and

Concentration Funds Districtwide

Enrollment of intended student groups that is

55percent or more of total enrollment

A district may spend supplemental and concentration

funds districtwide if the following are true:

• It identifies in its LCAP those services that are

funded and provided on a districtwide basis.

• It describes in its LCAP how such services are

principally directed toward and are effective in

meeting its goals for its intended student groups

in state and local priority areas.

Enrollment of intended student groups that is less

than 55 percent of its total enrollment

A district may spend supplemental and concentration

funds districtwide if:

• It follows the two bulleted items above.

• It describes how those services are the most

effective use of the funds to meet its goals for

its intended student groups in state and local

priority areas. The description must provide the

basis for this determination including but not

limited to, any alternatives the district considered

and any supporting research, experience, or

educationaltheory.

Source: State regulations.

California State Auditor Report 2019-101

November 2019

22

how they had principally directed their districtwide spending of

supplemental and concentration funds toward intended student

groups. e LCAPs for the three districts we visited indicate that the

districts intended to spend supplemental and concentration funds to

pay for varying proportions of districtwide services, such as reducing

class sizes and providing parent and community resource centers.

e proportions of the districts’ services that were districtwide

ranged from to percent. However, the districts did not always

clearly describe in their LCAPs how they principally directed those

funds toward intended student groups. Specifically, for of the

expenditures we reviewed from fiscal years – and –,

the information that the three districts provided in their LCAPs was

not sufficient for us to determine whether the districtwide services

on which they planned to spend supplemental and concentration

funds would principally benefit intended students.

For example, for six of the services we tested from its –

LCAP, Clovis Unified stated that services will be principally directed

without explaining how the district will principally direct them.

In one instance, Clovis Unified wrote in its LCAP that it would

“provide professional development…, train highly qualified teachers,

and develop new curriculum units and assessments… to ensure

all students, principally directed toward [the intended student

groups], achieve at a high level.” When we asked Clovis Unified for

clarification, an assistant superintendent stated that the district

focused these services—including professional development for

teachers—on helping intended student groups. It attributed the lack

of clarity in its LCAP to the vagueness in regulations about how

districts can principally direct services toward intended student

groups. However, when districts fail to clearly explain in their LCAPs

how they plan to use supplemental and concentration funds on

districtwide services to benefit intended student groups, they reduce

transparency and accountability.

In addition, a lack of clarity puts the districts at risk of stakeholders’

submitting complaints or filing lawsuits alleging that they have

inappropriately spent the funds. In fact, CDE’s records indicate

that since August , it has issued reports for complaints

against districts—five from January through April alone—in

which stakeholders raised concerns about districts’ intended use of

supplemental and concentration funds. One of those complaints

resulted in a lawsuit, which the parties involved ultimately settled

with the district agreeing to change how it uses supplemental and

concentration funds in the future.

Districts have not always clearly demonstrated how they planned

to spend supplemental and concentration funds districtwide, likely

in part because the requirements for doing so are vague. e LCFF

regulations, the CCSESA LCAP approval manual, and the LCAP

When districts fail to clearly explain

in their LCAPs how they plan to use

supplemental and concentration

funds to benefit intended student

groups, they reduce transparency

and accountability.

23California State Auditor Report 2019-101

November 2019

template all fail to explain or provide examples of ways a district

can successfully demonstrate how its districtwide spending is

“principally directed” toward intended student groups. Although the

LCFF regulations regarding districtwide spending of supplemental

and concentration funds have been in place since , stakeholder

complaints demonstrate that some districts struggle to successfully

describe how they principally direct those funds toward intended

student groups.

Despite the difficulties that some districts have

faced in implementing the spending requirements,

CDE has not fully incorporated into its key guidance

documents the position that it has taken in its

complaint reports regarding satisfying the spending

regulations. On at least eight occasions since

May, CDE has presented a consistent position in

its reports about how districts can comply with the

regulations for districtwide spending. We summarize

CDE’s position in the textbox. Because CDE’s

comments in its complaint reports provide more

specific advice to the districts named in the reports

regarding how they can demonstrate in their LCAPs

their compliance with the spending regulations, we

would have expected it to include this information in

the LCAP template instructions to ensure consistent

understanding among all districts.

Furthermore, based on the complaints and appeals

it receives, CDE could identify common pitfalls

for districts to avoid and best practices for them to

follow and could include this information in key

guidance documents, such as the LCAP template

and its instructions. According to the administrator

of CDE’s Local Agency Systems Support Office,

CDE has provided information regarding principally

directed from relevant complaints in recent

presentations. Nevertheless, of the descriptions

of the districtwide services we reviewed from our

selected districts’ fiscal year– LCAPs were

not in accordance with the guidance in CDE’s

complaintreports.

In addition, districts sometimes did not clearly

demonstrate how districtwide expenditures of

supplemental and concentration funds principally

benefited intended student groups because they used these funds for

base services that they provide to all students. Specifically, all three

districts and all threecounty offices we reviewed indicated that LCFF

base funding amounts do not cover all necessary base costs, which can

Key Information Regarding Complaints About

Districtwide Spending That the LCAP Template

Instructions Do Not Include

• “To provide the required justification for services

provided on a ‘wide’ basis, a district must distinguish

between services directed toward [intended student

groups] based on that status, and services available

to all students without regard to their status [in an

intended student group].”

• “A district should explain in its LCAP how it

considered factors such as the needs, conditions,

or circumstances of its [intended student groups],

and how the service takes these factors into

consideration (such as, by the service’s design,

content, methods, or location).”

• “A district must explain how the service will be

effective in meeting the LCAP goals for its [intended

student groups] by explaining how it believes

the service will help achieve one or more of the

expected outcomes for thegoal.”

• “Conclusory statements that a service will help

achieve an expected outcome for the goal, without

an explicit connection or further explanation as to

how, are notsufficient.”

• “Simply stating that a district has a high enrollment

percentage of [intended student groups] does not

meet this standard [increase or improve services]

because serving students is not the same as

enrolling students.”

Source: Analysis of a selection of CDE’s reports under

its complaint process, including appeals, and the LCAP

templateinstructions.

California State Auditor Report 2019-101

November 2019

24

put pressure on districts to use supplemental and concentration funds

to provide such services. Consequently, we observed that districts used

supplemental and concentration funds to pay for what appear to be

base services. For instance, San Diego Unified budgeted . million in

supplemental and concentration funds for library services at all schools

within the district. It justified the expenditure by mentioning that such

services create equitable access to learning tools, resources, materials,

and technology. According to the district’s LCAP, providing library

services on campus allows intended student groups an equitable

opportunity to succeed educationally through access to computers,

laptops, books, reference materials, and educational software.

Although we recognize the benefits of base services and the dilemma

districts face when they lack the funding necessary to pay for them,

this description fails to sufficiently explain how San Diego Unified

principally directed these services toward intended student groups.

LCAPs Have Not Consistently Provided Transparency or Facilitated

Accountability

e information districts include in their LCAPs is often overly

complex and unclear, resulting in LCAPs that are not consistently

transparent and that do not facilitate accountability. For example,

the LCAP template and instructions prompt districts to connect

their identified needs with goals based on those needs and then to

identify services to meet those goals. However, we rarely found this

logical connection in the LCAPs we reviewed. Likewise, districts

often did not effectively analyze in their LCAPs whether services

that they had already implemented had been successful. e lack of

clear information within the LCAPs raises concerns about the ability

of stakeholders to hold the districts accountable for the services

they provide, even though enabling such accountability is one of the

fundamental purposes that the LCAPs should serve. Weaknesses in

the template and limited reviews requiredof the county offices have

also contributed to the LCAPs’ lack oftransparency.

The LCAPs We Reviewed Did Not Clearly Communicate Whether the

Districts Had Effectively Met Students’ Needs

Guidance for developing quality LCAPs states that an LCAP should

establish a clear understanding of the services that each district will

provide to its students and should offer a simple and complete story

of that district’s needs, goals, services, and investments in positive

outcomes for its students. We believe that to be clear and effective,

an LCAP should logically connect a district’s needs and goals,

include sufficiently detailed descriptions of the related services, and

present understandable content. However, the LCAPs we reviewed

were unclear in a number of ways.

To be clear and effective, an

LCAP should logically connect a

district’s needs and goals, include

sufficiently detailed descriptions

of the related services, and present

understandable content.

25California State Auditor Report 2019-101

November 2019

First, the three districts did not always base the goals and services

in their LCAPs on clearly articulated needs. is approach

limits transparency because stakeholders cannot decipher

which problems the districts intend the goals to address or how

planned services will help the districts achieve those goals. e

primary causes of this misalignment are broad goals and a lack of

articulation about how certain services connect to the overarching

need and goal. In particular, each of the goals we reviewed from

the three districts’ – LCAPs was broad. For example, Clovis

Unified’s first goal is “Maximize achievement for ALL students,”

which does not convey any information about which types of