InternatIonal Monetary Fund

Middle East and Central Asia Department

Toward New Horizons

Arab Economic Transformation Amid Political Transitions

Prepared by a staff team led by Harald Finger and Daniela Gressani,

comprising Khaled Abdelkader, Khalid AlSaeed, Alberto Behar, Sami Ben Naceur,

Christine Ebrahimzadeh, Asmaa El-Ganainy, Samar Maziad, Aiko Mineshima,

Pritha Mitra, Preya Sharma, Charalambos Tsangarides, and Zeine Zeidane

Toward New Horizons

Arab Economic Transformation Amid Political Transitions

Middle East and Central Asia Department

Prepared by a staff team led by Harald Finger and Daniela Gressani,

comprising Khaled Abdelkader, Khalid AlSaeed, Alberto Behar, Sami Ben Naceur,

Christine Ebrahimzadeh, Asmaa El-Ganainy, Samar Maziad, Aiko Mineshima,

Pritha Mitra, Preya Sharma, Charalambos Tsangarides, and Zeine Zeidane

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

© 2014 International Monetary Fund

Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Joint Bank-Fund Library

Toward new horizons: Arab economic transformation amid political

transitions / prepared by a staff team led by Harald Finger and

Daniela Gressani comprising Khaled Abdelkader [and eleven

others]. – Washington, D.C. : International Monetary Fund, c2014.

“Middle East and Central Asia Department.”

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN 978-48431-146-2

1. Economic development—Arab countries. 2. Arab countries—

Economic policy. 3. Fiscal policy—Arab countries. 4. Monetary

policy—Arab countries. 5. Foreign exchange rates—Arab countries.

I. Finger, Harald. II. Gressani, Daniela, 1956– III. Abdelkader,

Khaled. IV. International Monetary Fund. V. International Monetary

Fund. Middle East and Central Asia Department.

HC498.A73 2014

Disclaimer: The views expressed herein are those of the authors and

should not be reported as or attributed to the International Monetary

Fund, its Executive Board, or the governments of any of its member

countries.

Please send orders to:

International Monetary Fund, Publication Services

P.O. Box 92780, Washington, DC 20090, U.S.A.

Tel.: (202)623-7430 Fax: (202)623-7201

E-mail: [email protected]

Internet: www.imfbookstore.org

iii

Contents

Acknowledgments vii

Preface ix

1. Introduction and Summary 1

2. Tackling Fiscal Challenges 8

3. Monetary and Exchange Rate Policy for Stability, Growth,

and Jobs 29

4. Bolstering Financial Stability and Development 40

5. Reform for Sustainable, Job-Creating, Private Sector–Led Growth 61

6. Managing Economic Change During the Transitions 83

References 97

Boxes

Box 2.1. Mixed Public Views on Cutting Energy Subsidies 16

Box 2.2. Progress on Decentralization 21

Box 2.3. Tax Potential and Revenue Gaps in Non-Oil ACTs 24

Box 6.1. A Stylized Approach to Building Coalitions 89

Box 6.2. Continuing Need for Stepped-Up Donor Support 93

Box 6.3. Lessons from the Arab Transitions for the IMF 94

Figures

Figure 2.1. Fiscal Positions Have Deteriorated 9

Figure 2.2. Subsidies, Transfers, and Wages Were Raised 9

Figure 2.3. Crowding Out of Private Sector Credit, 2010–13 10

Figure 2.4. Government Finances 11

Figure 2.5. A 5 Percent of GDP Increase in Public Investment

Would Signifi cantly Impact Growth and Employment 13

Figure 2.6. High Public Wage Bills 14

Figure 2.7. High Public Wages Tend to Raise Inequality 15

Figure 2.8. Large Variation in the Quality of Public Investment Management

18

CONTENTS

iv

Figure 2.9. Scope for Additional Revenue Collection

22

Figure 2.10. Scope for Raising Property and Excise Tax Rates

28

Figure 3.1. Signifi cant Macroeconomic Impacts from the

Political Transitions

30

Figure 3.2. External Developments

31

Figure 3.3. International Reserves Have Dropped Since the Onset

of the Transition

32

Figure 3.4. Infl ation in Most ACTs Has Remained below the Emerging

Market Average

33

Figure 3.5. Real Effective Exchange Rates Have Appreciated in Some ACTs

Figure 3.6. Real and Nominal Volatility, 2000–12

36

Figure 4.1. Bank Credit is Large in Most ACTs

40

Figure 4.2. Few Firms Use Bank Credit to Finance Investments

41

Figure 4.3. Relatively Few People in the ACTs Maintain Bank Accounts

42

Figure 4.4. Access to Finance is a Major Constraint

42

Figure 4.5. Nonperforming Loans are High

43

Figure 4.6. ACTs Rank Last in Legal Rights

43

Figure 4.7. Bank Concentration is High

44

Figure 4.8. Government Debt Markets Remain Underdeveloped

44

Figure 4.9. Stock Markets are Large in Some ACTs

45

Figure 4.10. Private Institutional Investors are Lacking in Some Countries

46

Figure 4.11. Potential for Developing the Investor Base

51

Figure 4.12. Global Assets of Islamic Finance Have Grown

55

Figure 5.1. Lagging Growth and High Unemployment

62

Figure 5.2. More Investment is Needed to Support Growth

62

Figure 5.3. Large Potential for Higher Exports

64

Figure 5.4. Strong Trade Links with Europe

64

Figure 5.5. Signifi cant Trade Barriers

65

Figure 5.6. Intraregional Share of Exports and Stock of Foreign Direct

Investment

65

Figure 5.7. Improvements from Trade Facilitation in Morocco

67

Figure 5.8. Business Licensing and Permits are Major Constraints

68

Figure 5.9. Governance and Corruption are Increasingly Serious

Concerns

69

Figure 5.10. Doing Business Rankings Improve with Income

70

Figure 5.11. Doing Business Reform Efforts Have Been Set Back

70

Figure 5.12. Excess Labor Regulations and Education Mismatches

72

34

Contents

v

Figure 5.13. Large Total and Youth Unemployment

72

Figure 5.14. The Public Sector is a Large Employer in MENA

74

Figure 5.15. Government is the Preferred Employer for Arab Youth

74

Figure 5.16. Rural Poverty is Signifi cant

77

Figure 5.17. Many People are Vulnerable to Falling into Poverty

77

Figure 5.18. Social Safety Nets are Small

78

Figure 5.19. Social Safety Net Coverage is Limited

79

Figure 5.20. Limited Awareness of Social Safety Nets in the Lowest

Income Quintile

79

Figure 6.1. Political Risk Has Increased

84

Figure 6.2. Perception of Arab Youth about Direction of the Economy

85

Figure 6.3. Rule of Law Ranking Shows Room for Improvement

86

Figure 6.4. Government Effectiveness Has Suffered in Most ACTs

87

Tables

Table 2.1. Room for Improvement in Tax Effort and

VAT Collection Effi ciency

22

Table 2.2. Non-Oil ACTs: Base Broadening Recommendations

26

Table 2.3. Scope for More Income Tax Progressivity

27

Table 3.1. Structural and Exchange Rate Characteristics

33

Table 5.1. Poverty Remains an Important Concern

77

Table 6.1. Strong Use of Social Networks for Political and Community Views

91

This page intentionally left blank

vii

Acknowledgments

The paper is the outcome of an interdepartmental project of the IMF’s

Middle East and Central Asia Department with the Communications, Fiscal

Affairs, Monetary and Capital Markets, Research, and Strategy, Policy, and

Review Departments.

The authors would like to thank Masood Ahmed, Director of the Middle

East and Central Asia Department, for his guidance and comments. They are

also thankful for advice and support in coordination from Prakash Loungani,

David Marston, Marco Pinon, Christoph Rosenberg, and Abdel Senhadji; and

for guidance on political economy issues from Raj Desai.

Thanks are also due to Yasser Abdih, Abdul Malik Al-Jaber, Nabil Ben Ltaifa,

Ralph Chami, Jean-François Dauphin, Shantayanan Devarajan, Ishac Diwan,

Gilda Fernandez, Edward Gemayel, Christopher Jarvis, Juha Kähkönen,

Alfred Kammer, Kristina Kostial, Inutu Lukonga, Amine Mati, Tokhir

Mirzoev, Eric Mottu, Gaelle Pierre, Bjoern Rother, Randa Sab, Nasser Saidi,

Hossein Samiei, Carlo Sdralevich, Gazi Shbaikat, Natalia Tamirisa, Shahid

Yusuf, and Younes Zouhar for providing comments at various stages of

drafting the paper.

Special thanks are due to Gohar Abajyan and Jaime Espinosa-Bowen for their

research assistance, Kia Penso for her editorial contributions, Cecilia Prado

de Guzman for assistance with formatting and document preparation, and

Joanne Johnson and Katy Whipple for editorial guidance and production

support.

This page intentionally left blank

ix

Preface

The transformations in the Arab world that began three years ago had their roots not

only in demands for more voice and participation but also in a growing frustration with

the economic environment where job opportunities were few and connections seemed

to be more important than merit in accessing the gains from economic growth. Since

then, governments in these countries have been pursuing country-specifi c agendas of

political and constitutional reform, but they have also had to grapple with heightened

macroeconomic vulnerabilities, the effect, in part, of a worsening international, regional,

and domestic environment on private sector confi dence and growth. The near-term

economic outlook continues to be challenging and subject to downside risk, and so the

focus on maintaining macroeconomic stability will remain a key priority for the coming year.

However, it is also important for these governments to embark on the bold reform

agendas that will make for more dynamic and inclusive economies, generate more

jobs, and provide equal access to economic opportunity for all segments of society.

Unless strong economic and fi nancial reforms are implemented, a gradual economic

recovery will not be enough to bring a meaningful reduction in the region’s high rates of

unemployment in coming years, particularly among women and youth.

Realizing the economic potential of the Arab Countries in Transition lies fi rst and

foremost in the hands of countries’ governments. But the international community,

including the IMF, can help. With the benefi t of hindsight, it has become clear that

in past years we paid insuffi cient attention to growing socioeconomic imbalances and

unequal access to economic opportunity. The Arab transitions have thus prompted us

to step back and rethink our approach to economic policy recommendations for the

countries undergoing transition. While we have been actively engaged in all transitioning

countries, with a focus on macroeconomic stabilization and policies in support of

economic development, we have to date not laid out our comprehensive view on

the macroeconomic and structural policies that we see as essential for safeguarding

macroeconomic stability and putting in place the right conditions for high, sustainable,

and inclusive growth. This publication attempts to fi ll that gap and to provide our

intellectual contribution to the ongoing discussion on setting the right policies in the

Arab Countries in Transition.

In this spirit, I hope that this publication will be of use for policymakers and other

stakeholders in the countries undergoing transition, and for the international community

that supports them, in order to enable an economic transformation that will respond to

the hopes and aspirations of their young and dynamic population.

Masood Ahmed

Director, Middle East and Central Asia Department

International Monetary Fund

This page intentionally left blank

1

CHAPTER

Introduction and Summary

The political transitions in the Arab world have created an opportunity

for economic transformation. The political landscape is changing and new

stakeholders have become active, while old vested interests standing in the

way of reform may have been weakened. This setting provides a historic

opportunity to rethink the economic reform agenda and tackle longstanding

economic issues that were previously diffi cult to approach.

Nevertheless, three years after the onset of political transition in the Arab

world, managing the transitions and implementing necessary economic

policies has proven to be challenging. The Arab Countries in Transition

(ACTs), including countries that have undergone regime change (Egypt,

Libya, Tunisia, Yemen) and those that have engaged in transformation under

existing regimes ( Jordan, Morocco), have progressed along their transition

paths. Governments with limited horizons and mandates, institutional

uncertainty, and socioeconomic tensions have been hindering, to varying degrees

across countries, the focus on the economic transformation agenda. At the

same time, challenges in economic management have intensifi ed, as external

and domestic economic conditions have been complex, policy buffers are

running low, and economic growth is insuffi cient to bring down the ACTs’

high unemployment. In this setting, countries are at a critical juncture: prudent

economic management, paired with bold reform efforts to create an enabling

environment for private sector–led growth, will be needed to safeguard the

promise of the Arab transitions for better living conditions, higher and more

inclusive growth, and job creation on a meaningful scale.

The ACTs have been facing a number of longstanding economic challenges.

Well before the beginning of the transitions in 2011 in economic growth

per capita and integration into the world economy they were lagging behind

other emerging market and developing countries (EMDCs), and there was

a perceived lack of competition in domestic markets. Unemployment in the

ACTs was high, running at more than double the average rate of EMDCs,

and youth unemployment was among the highest in the world. There was a

1

TOWARD NEW HORIZONS

2

widespread perception that the benefi ts of growth were chiefl y captured by

the well-connected, while others felt marginalized. Many countries carried

substantial public debt, and some were running high fi scal defi cits. The ACTs’

tendency to limit movements in their exchange rates helped provide an anchor

for infl ation but also constituted an important source of vulnerability.

The private sector has lacked the dynamism needed for sustained job-

creating growth. It has been stifl ed by government intervention: complex

and burdensome business regulation has constrained economic activity

and enabled corruption; state-owned enterprises and public banks have

often been dominant players in their sectors but have tended to operate

ineffi ciently, leading to fi scal slippages and capital misallocation; and lack of

a level playing fi eld between public and private enterprises, as well as among

private enterprises, has limited competition and innovation. Perceptions of

government effectiveness and control of corruption have been deteriorating

over time, and governments have been unable to create the infrastructure

needed to support a dynamic economy. As a consequence, competitiveness

has suffered. Where reforms were initiated, their top-down approach

has often meant that the resulting economic benefi ts went largely to the

well-connected without generating tangible benefi ts for most people—in

particular, without creating formal sector jobs or improving living standards.

Shortcomings in access to fi nance, trade integration, infrastructure

investment, and the labor market and education system have also hampered

private sector–led growth. Access to fi nance by businesses has been among

the lowest in the world, constraining private investment. A lack of trade

integration (and supporting policies) has meant that the region’s exports

have been far below their potential. Inadequate labor regulations have been

disincentives to private sector hiring, while the public sector has often taken

the role of employer of fi rst and last resort—a role that has distorted the

labor market and education system, and one that governments can no longer

afford to play. In addition, ACTs, like other countries in the MENA region

more generally, have maintained large generalized subsidies as their main

vehicle for social protection. These subsidies are ineffi cient—their benefi ts

accrue disproportionately to the wealthy—and they tie up scarce resources

that could be used for much-needed priority expenditure in areas like

infrastructure investment, health, and education.

These problems have become more acute since the onset of transitions in

2011, as popular expectations for better living standards have risen. The

ACTs have been faced with an economic downturn resulting from transition-

related disruptions, regional confl ict, an unclear political outlook, eroding

competitiveness, a challenging external economic environment in the context

of the European crisis, and declining confi dence. This downturn has worsened

the unemployment problem and led to stagnating living standards, and may

have reduced the medium-term growth potential in some countries, putting

Introduction and Summary

3

economic realities squarely at odds with the aspirations of the population

for an economic transformation that would provide quick returns in the form

of job creation and income generation. Demographic pressures suggest that,

under current baseline projections for GDP growth through 2018 of around

4¼ percent in the oil-importing ACTs, unemployment is expected to continue

rising. At the same time, fi scal defi cits and public debt have further increased,

and international reserve buffers have been run down, severely limiting the

policy space for expansionary economic policies in the period ahead.

In this setting, the ACTs risk getting trapped in a vicious circle of economic

stagnation and persistent sociopolitical strife. As economic realities fall behind

populations’ expectations, there is a risk of increased discontent, which could

further complicate the political transitions, impairing governments’ mandates

and planning horizons and, consequently, their ability to implement the

policies necessary to catalyze the much-needed economic improvement.

The political transitions have thus created not only new opportunities for

economic transformation but also the necessity to accelerate economic

reform. Strong economic management, and policies to bolster the business

environment, are needed to avoid a vicious circle and create in its place

a virtuous one where the right policies revive economic confi dence and

generate inclusive economic growth. Better economic conditions can then

help reduce discontent and thereby smooth the political transitions.

The ACTs need a medium-term vision to set policies for their economic

future. Goals will differ among countries, refl ecting their citizens’ aspirations;

but in all countries they need to be framed in an economic model that

provides a more level playing fi eld, allows for greater integration into the

global economy, and creates an environment in which a dynamic private

sector can drive growth and create suffi cient jobs for a growing labor force,

while governments provide adequate infrastructure and regulation, along with

basic services and targeted social protection.

At this critical juncture, three economic policy priorities are essential: enabling

additional job creation in the near term to lessen the risk of a vicious circle;

addressing macroeconomic vulnerabilities to safeguard economic stability; and

setting in motion necessary reforms to generate higher potential growth and

job creation in the coming years.

Near-term policies need to focus on quickly enabling job creation in order

to lessen the adverse impact of the post-Arab-Spring economic downturns.

Delays in the revival of private investment, in the context of impaired

economic confi dence, indicate a need for governments to shore up economic

activity in the near term. Experience from other countries suggests that well-

designed infrastructure projects can create jobs and lay a better foundation for

private sector activity. With little room for further widening of fi scal defi cits

TOWARD NEW HORIZONS

4

in many countries, spending needs to be reoriented toward growth-enhancing

and job-creating public investment that stimulates private sector activity,

while protecting vulnerable groups through well-targeted social assistance.

Expenditure-side reforms should include redirecting social protection from

expensive and ineffi cient generalized subsidies to transfers that better target

the poor and vulnerable. In addition, containing public wage bills would

reduce expenditure rigidities and support fi scal strategies for sustainability and

private sector job creation. Revenue measures should focus on broadening the

tax base and improving the effi ciency of tax collection. Some ACTs also have

room for raising income tax progressivity and increasing excise and property

tax rates. Together, these policies would enhance equity while freeing scarce

resources for priority expenditure in infrastructure investment, health, and

education.

At the same time, near-term policies need to be anchored in medium-term

policy frameworks that maintain and strengthen economic stability. With

concerns about debt sustainability rising and fi scal and external buffers

eroding, countries need to anchor their fi scal policies in medium-term

frameworks that safeguard macroeconomic stability and debt sustainability.

In some cases, there may be room for scaling up defi cits in the near term

when adequate fi nancing is available and in the context of medium-term

adjustment programs. The slower the pace of fi scal adjustment, the larger the

fi nancing needs will be, underscoring the need to anchor policies in credible

medium-term consolidation plans; these will help secure the continued

willingness of creditors to provide the necessary fi nancing.

Countries face trade-offs in monetary and exchange rate policy. Each country

will need to weigh the pros and cons of pegging versus exchange rate

fl exibility on an individual basis. Infl ation will need to be kept contained,

and infl ation expectations well anchored. At the same time, a key near-term

challenge is to safeguard aggregate demand in the face of weak growth and

necessary fi scal consolidation. In addition, capital fl ows must be restored

so as to reverse the decline in reserves. This outcome would come from a

credible monetary and exchange rate policy that reduces the impact of real

shocks, supports measures to increase competitiveness, controls infl ation, and

thus lays out a path for stable and job-creating growth. For countries that opt

for greater exchange rate fl exibility, this would require the establishment of

a new anchor for monetary policy and stepped up technical capacity at the

central bank, while pegging implies the need to align fi scal policy closely with

macroeconomic objectives.

Bolstering fi nancial sector development will be essential to underpin

the recovery and broaden access to fi nance for investment and growth.

Limited bank competition, a concentration of lending to large, established

companies, a generally poor fi nancial infrastructure, and underdeveloped

capital markets suggest that large benefi ts could be gained from strengthening

Introduction and Summary

5

fi nancial development and access to fi nance, and thereby bolstering

investment, growth, and job creation. Reforms should focus on increasing

competition among banks and strengthening their fi nancial infrastructure,

deepening capital markets and developing their investor base, and making

available alternative fi nancing instruments, Islamic fi nance, and microfi nance.

A bold economic reform agenda will be essential for propelling private sector

activity and fostering a more dynamic, competitive, innovation-driven, and

inclusive economy. To achieve broad-based and sustainable growth, countries

need to move gradually away from state-dominated to private investment, and

from protected and rent-seeking enterprises to export-led growth and value

creation. Policies should aim at strengthening the revival of private sector

confi dence and laying the foundations for higher potential growth. A key

goal will be to engineer a transformation for the public sector, a shift from

providing privileges such as public employment, subsidies, economic rents,

and tax exemptions, to providing basic economic services, adequate social

protection, better governance, a level playing fi eld for all economic actors, and

a competitive environment for the private sector. Countries will begin their

efforts from different starting points and will have different reform objectives,

but there are some common areas that should be covered: these include trade

integration, business regulation and governance, labor market and education

reform, improved access to fi nance, and better social safety nets (SSNs).

Deepening trade integration can offer signifi cant benefi ts. In addition to the

large potential direct gains of boosting exports and attracting productivity-

enhancing FDI, trade integration can serve as catalyst for reforms in other

areas that will help countries compete. Deeper trade integration will require

better access to advanced economy markets. It will also involve carefully

reducing further the ACTs’ tariffs and non-tariff trade barriers, and focusing

on the increasingly important areas of trade facilitation and export promotion .

Complex and burdensome business regulation needs to be tackled to unleash

entrepreneurial activity and private investment. It is essential to improve

the systems of checks and balances in domestic institutions to prevent the

exercise of arbitrary discretion and nontransparent intervention, and to

streamline business regulation with a view to cutting red tape and reducing

informality and corruption. Institutional and regulatory reform should aim at

reducing the scope for discretion, improving transparency, and strengthening

institutional autonomy and accountability.

Labor market and education reforms can provide incentives for hiring and

participation in the formal private sector labor market. Countries should

review labor market regulations with a view to reducing distortions that

discourage hiring and skills-building, while ensuring an adequate level

of social protection. Governments need to revisit their recruitment and

compensation policies to ensure that hiring does not exceed needs and salaries

TOWARD NEW HORIZONS

6

do not bias job-seekers toward the public sector. Education systems should

be improved and reoriented towards skills needed in the private sector. As

these policies take time to yield tangible results, countries should consider

employing active labor market policies to achieve quick improvements in labor

market outcomes.

Countries need to create effi cient SSNs to protect the poor and vulnerable in

cost-effective ways. In transitioning from costly generalized subsidies to

targeted forms of social protection, countries should increase their

spending on existing safety net programs and improve their coverage;

consolidate existing, fragmented SSNs; prioritize interventions such as

conditional cash transfers that strengthen human capital; invest in SSN

infrastructure such as unifi ed registries for benefi ciaries; increase the use

of modern targeting techniques; strengthen governance and accountability

in SSNs; and step up communication to potential benefi ciaries about the

programs available to them.

The complexity of all these tasks requires careful prioritization and

sequencing. Although countries differ in their starting conditions and will

need to tailor their individual reform plans, the scope for macroeconomic

and structural policies to support growth and maintain stability is substantial

in all of them. At the same time, the political transitions are at differing

stages among the ACTs, and in some countries transitional governments with

short horizons and limited mandates have less room to maneuver when

setting in motion the necessary policy reforms. In addition, the administrative

capacity to execute reforms differs among countries and is limited in some

of them. Careful prioritization and sequencing of reforms is thus required

to make effi cient use of political capital and administrative capacity, and the

complexity of the political transitions requires a fl exible approach so that

opportunities for reform can be seized as they arise. It will also be critical to

identify those measures that can be taken quickly to produce strong effects,

such as streamlining business regulation and improving the transparency

of the budget process. Enacting this type of reform quickly would help

strengthen confi dence in the authorities’ commitment to the reform process.

In an evolving sociopolitical environment, careful consideration of political

economy has become crucial. Complex political processes, transition

governments with short horizons, the emergence of new stakeholders,

the growing importance of social media in the political process, increasing

polarization of society, and a diffi cult security environment make for

challenging and uncharted territory. To set in motion a virtuous circle where

political transition and economic transformation reinforce one another to

generate higher confi dence and higher growth, policymakers need to employ a

participatory approach, engaging with different segments of society, creating

a sense of urgency for reform and showcasing its benefi ts, listening to

stakeholders’ views, and building coalitions for reform. Policy plans also

Introduction and Summary

7

need to include effective communication plans. Governments must be able to

explain persuasively the reasoning behind diffi cult decisions if people are to

support them.

Stepped-up support from the international community will also be

critical. Even as countries need to stay in the driver’s seat and plan their

policy programs through wide national consultation, there is a need for

the international community to support the ACTs’ policy efforts along

four dimensions. Bilateral and multilateral partners will need to continue

providing signifi cant fi nancing, increasing the scale in some cases, so that

public spending can support growth and, where necessary, ease the pace of

adjustment. Access for the ACTs’ exports to advanced economies’ markets is

also important, to support the economic recovery and raise potential growth.

The ACTs can also profi t from policy advice from their international partners

in many areas of economic policy. In addition, the international community

can help in capacity-building efforts by providing technical assistance and

training.

The IMF remains closely engaged with the ACTs. IMF staff are engaging

with country authorities and their international partners in the areas of

economic policies, fi nancing, and capacity building. The IMF has committed

about $10 billion in fi nancial arrangements with Jordan, Morocco, Tunisia,

and Yemen. IMF staff are in discussions with Yemen toward a successor

arrangement to the IMF support in 2012, and are supporting Egypt and Libya

through policy dialogue and capacity-building efforts.

This paper lays out key elements of reform in the area of economic policy

for the ACTs. While individual countries will design specifi c reform programs

based on their starting positions and reform goals, a number of reform

areas will be common for them. This paper discusses shared priorities and

lessons. Chapter 2 highlights policies to address the fi scal challenges, while

Chap ter 3 discusses aspects of monetary and exchange rate policies to

support near-term stabilization and stable medium-term growth. Chapter 4

raises issues related to fi nancial sector policies for stability and development,

including improving access to fi nance so as to catalyze inclusive growth.

Chapter 5 emphasizes a broad range of areas where economic reform could

generate higher potential growth and improved job creation in the medium

term. Chapter 6 focuses on important supporting factors that need to fall in

place to enhance the chances of successful policy outcomes. These include

the crucial areas of political economy, communication, and support from the

international community.

8

CHAPTER

Tackling Fiscal Challenges

The ACTs faced signifi cant medium-term fi scal challenges even before the

onset of their transitions. In many cases, fi scal defi cits and debt were higher

than in other emerging market and developing countries, refl ecting, to varying

degrees, generalized food and fuel subsidies, high global commodities prices,

low taxation, and countercyclical fi scal action in the context of the global

fi nancial crisis. Expenditures were dominated by rigid spending on wages and

subsidies, consuming 40 percent or more of most ACTs’ budgets and leaving

too little space for capital expenditures, which in some cases ran at half the

average of emerging and developing economies. Following the global fi nancial

crisis, all ACTs (except Libya) already had high or rising debt levels.

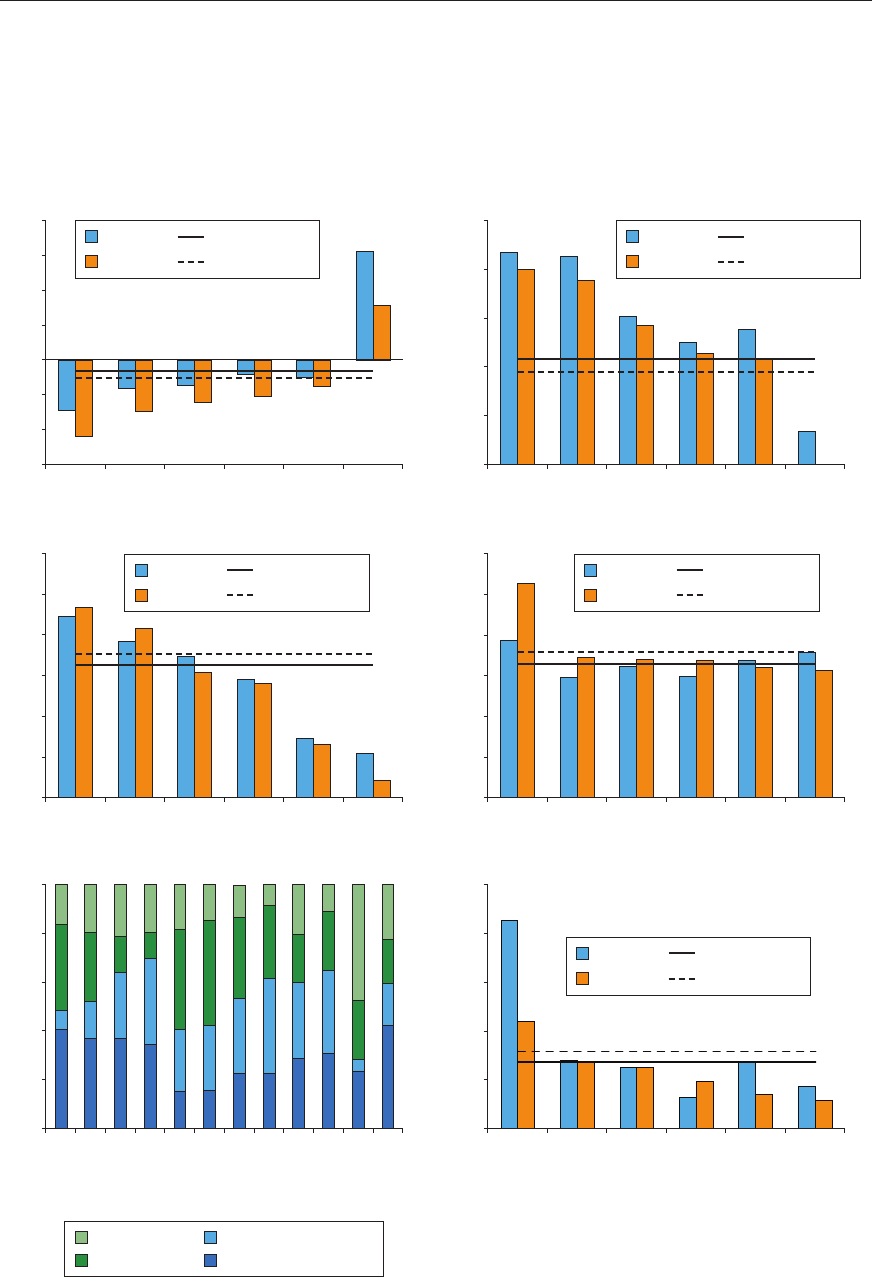

Spending hikes in the aftermath of the Arab Spring further raised fi scal

defi cits and public debt ( Figure 2.1 ). ACT governments attempted to address

pressing social needs and political tensions, and to sustain aggregate demand

by further raising public wage bills and generalized subsidies ( Figure 2.2 ).

1

In Egypt and Jordan, already sizeable defi cits increased sharply, lifting debt

above 80 percent of GDP by 2013. Despite moderate debt ratios in Morocco,

Tunisia, and Yemen, fi scal vulnerabilities were heightened by elevated

defi cits. Libya’s non-oil fi scal defi cit is close to 170 percent of GDP, the fi scal

breakeven oil price is $118 per barrel,

2

and the overall fi scal position returned

to a defi cit in 2013 as a consequence of renewed oil supply disruptions,

despite large oil reserves.

At the same time, these spending hikes failed to provide a lasting stimulus

to private sector activity. Raising generalized subsidies and public sector

wage bills provided a temporary boost to consumption but was ineffective

at stimulating the private investment needed to generate jobs and improve

living standards. Moreover, this new current spending was partially offset by

reductions in already low capital spending, and sometimes, also, by reductions

2

1

In Jordan, fiscal deficits also worsened because of quasi-fiscal activities and shortfalls in gas from Egypt, which

necessitated expensive fuel imports for electricity generation.

2

The fiscal breakeven oil price is the hypothetical price of oil at which an oil-exporting country’s budget would be balanced.

Tackling Fiscal Challenges

9

in maintenance, education, and health spending—all of which are integral to

sustained improvements in private sector activity. While weak demand has also

been a factor in explaining subdued credit growth, fi nancing of the resulting

large fi scal defi cits may be further hampering the recovery, by increasing the

cost of credit available for private sector activities and creating infl ationary

pressures ( Figure 2.3 ).

Figure 2.1 . Fiscal Positions Have Deteriorated

( Gross public debt and overall fiscal balance, average ; percent of GDP)

EGY

JOR

MAR

YMN

TUN

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

90

100

–16 –14 –12 –10 –8 –6 –4 –2 0

Public debt

Fiscal balance

2008–10

2013

Sources: National authorities; and IMF staff estimates.

Figure 2.2 . Subsidies, Transfers, and Wages Were Raised

(Changes in revenue and expenditure, 2010–13; percent of GDP)

–10

–8

–6

–4

–2

0

2

4

6

8

10

12

14

16

18

20

22

Egypt Jordan Libya Morocco Tunisia Yemen

Other expenditures

Capital expenditures

Subsidies and transfers

Wages

Total expenditures

Total revenues

–15

Sources: National authorities; and IMF staff estimates.

TOWARD NEW HORIZONS

10

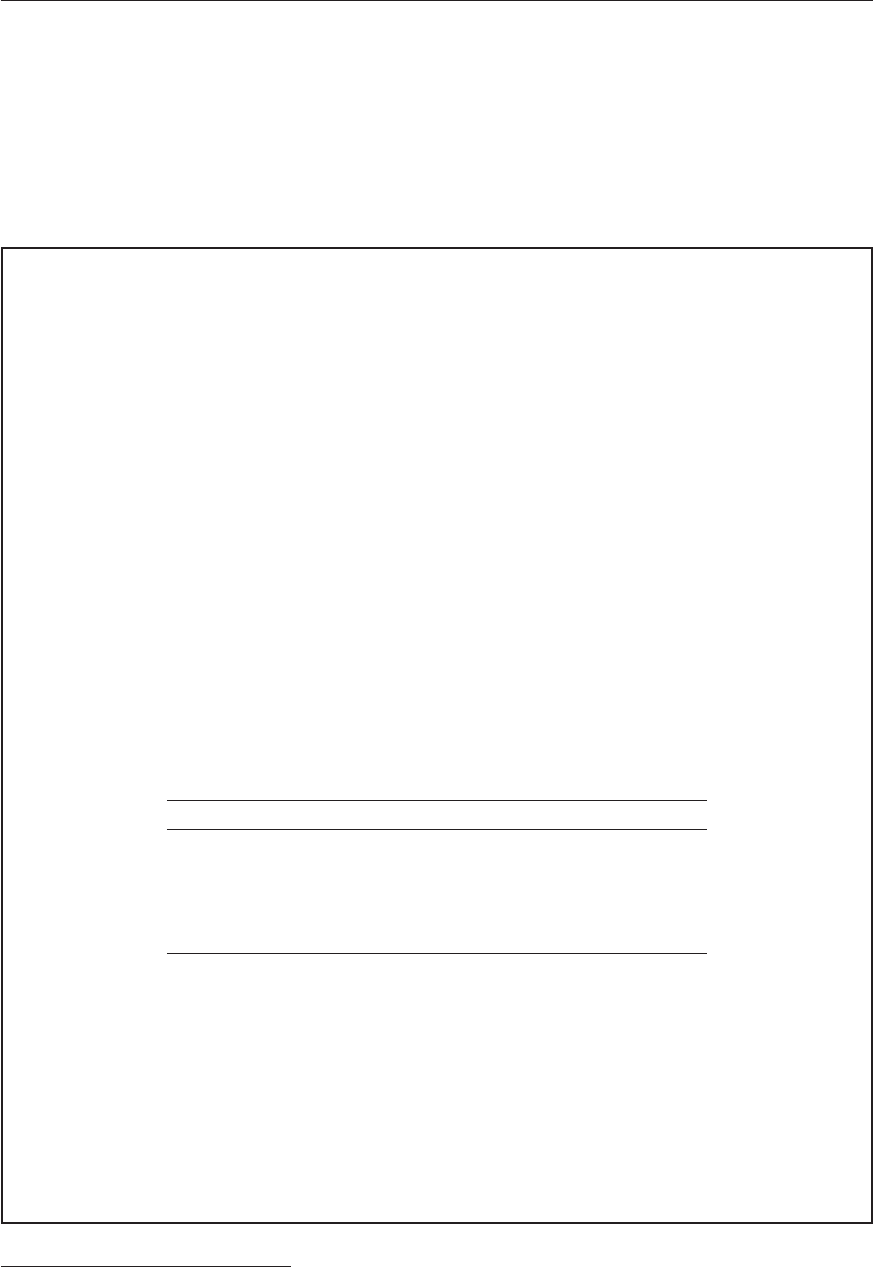

Figure 2.3 . Crowding Out of Private Sector Credit, 2010–13

DJI

EGY

JOR

LBN

MRT

MAR

PAK

SDN

TUN

WBG

–10

–5

0

5

10

15

–5 0 5 10 15 20

Change in credit to government

(Percent of GDP)

Change in credit to private sector

(Percent of GDP)

DJI

EGY

JOR

LBN

MRT

MAR

PAK

SDN

TUN

WBG

0

20

40

60

80

100

120

140

0 20 40 60 80 100 120 140

Growth in bank deposits

(Percent)

Growth in credit to central government

(Percent)

Source: National authorities; and IMF staff estimates.

In this environment, the demands on near- and medium-term fi scal policy are

substantial. Countries need to carefully reorient and sequence their near-term

policies, so that they are aimed at supporting growth and job creation within

binding resource constraints. Medium-term policies need to aim at clearly

anchoring fi scal stability and strengthening effi ciency.

Demands on near-term fi scal policy call for a reorientation of public

spending toward growth-enhancing and job-creating public investment that

stimulates private sector activity, and toward well-targeted social assistance

that protects vulnerable groups. Room for expansionary fi scal policy is

limited, given already high fi scal imbalances and fi nancing limitations

( Figure 2.4 ). Yet, with weak private sector confi dence, governments have to

take a lead role in shoring up economic activity in the near term. Achieving

this objective without raising defi cits and debt to unsustainable levels requires

mobilizing revenues and cutting current spending, which, for most ACTs,

means reducing spending on generalized subsidies and containing public

sector wage bills.

Although this approach is politically diffi cult, the risks to near-term economic

activity appear limited. In emerging and developing countries,

3

including the

ACTs, fi scal multipliers on current spending are smaller than those on capital

spending; cuts to current spending, therefore, pose less risk to near-term

economic activity. The pace of spending cuts should be designed to contain

the negative effects on growth, as these effects are amplifi ed when output

3

Ilzetzki, Mendoza, and Vegh (2011).

Tackling Fiscal Challenges

11

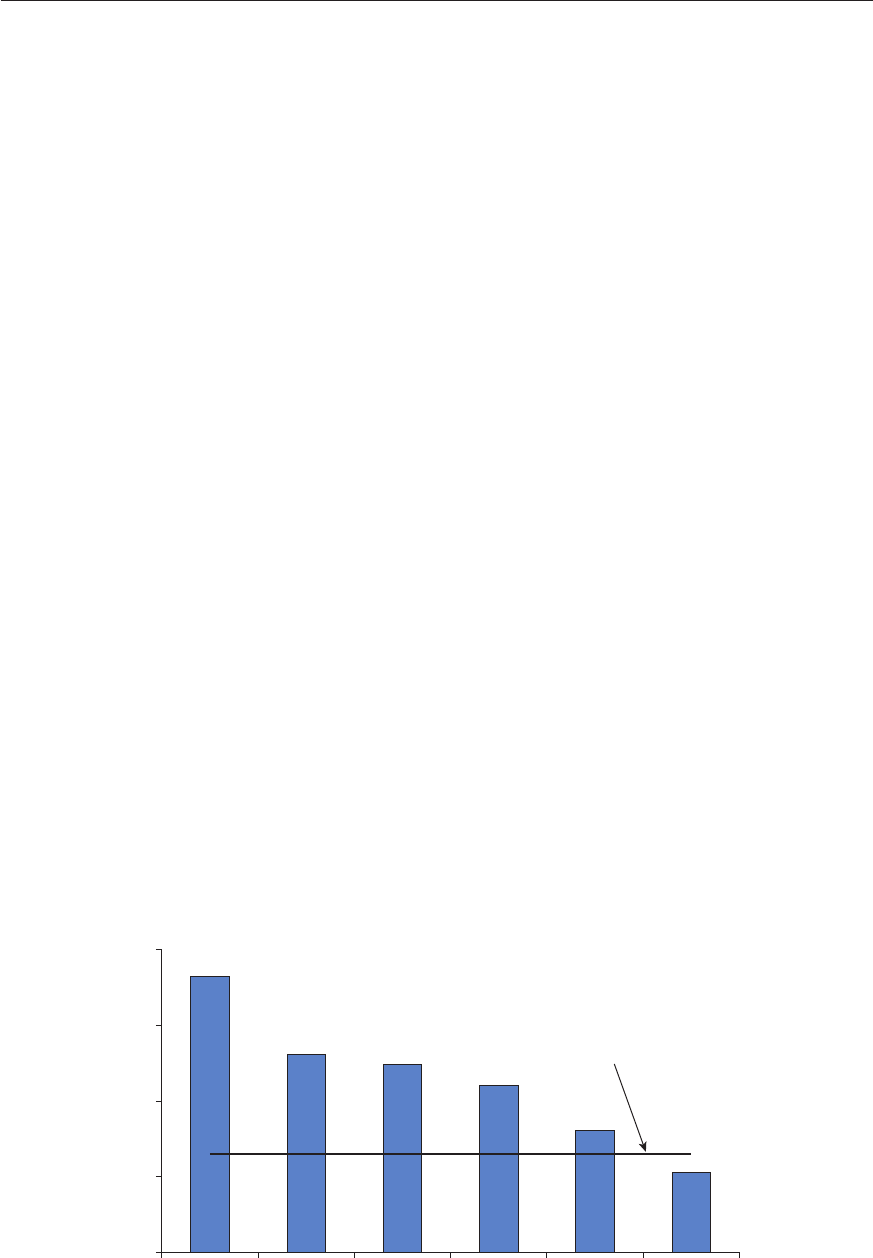

Figure 2.4 . Government Finances

(Percent of GDP)

–15

–10

–5

0

5

10

15

20

EGY JOR MAR YMN TUN LBY

General Government Balance

0

20

40

60

80

100

EGY JOR MAR YMN TUN LBY

General Government Debt

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

MAR TUN JOR EGY YMN LBY

Total Tax Revenue

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

LBY TUN EGY MAR YMN JOR

Total Expenditure

0

20

40

60

80

100

MAR 00–09

MAR 10–13

TUN 00–09

TUN 10–13

JOR 00–09

JOR 10–13

EGY 00–09

EGY 10–13

YMN 00–09

YMN 10–13

LBY 00–09

LBY 10–13

Expenditure Components

0

5

10

15

20

25

LBY JOR TUN MAR YMN EGY

Public Investment

1

2000–09

2010–13

EMDC 2000–09

EMDC 2010–13

2000–09

2010–13

EMDC 2000–09

EMDC 2010–13

2000–09

2010–13

EMDC 2000–09

EMDC 2010–13

2000–09

2010–13

EMDC 2000–09

EMDC 2010–13

2000–09

2010–13

EMDC 2000–09

EMDC 2010–13

Capital

Other Current

Subsidies and Transfers

Wages

Sources: National authorities; and IMF staff estimates.

Note: EMDC = emerging market and developing countries.

TOWARD NEW HORIZONS

12

4

Fiscal multipliers are defined as the ratio of a change in output to an exogenous change in government

spending or tax revenues. Several recent studies, including Auerbach and Gorodnichenko (2012) and Baum,

Poplawski-Ribeiro, and Weber (2012) find that fiscal multipliers are magnified in advanced economies when

output is below potential. This also holds for the ACTs, though revenue multipliers are estimated to be less

sensitive to output gaps.

is below potential (the current cyclical position of the ACTs).

4

In addition,

low tax revenues (relative to GDP) in most ACTs, combined with revenue

multipliers that tend to be lower than expenditure multipliers, support

immediate revenue mobilization. Appropriately chosen near-term revenue

measures—including broadening tax bases, raising income tax progressivity,

and increasing excise and property tax rates—would also improve the

redistributive impact of fi scal policy, which has so far been limited by

weak taxation (see Section B below). This fi scal policy mix would need to

be supported by adequate monetary policy, fi nancial sector policies, and

structural reforms ( Chapters 3 – 5 ) to raise growth.

All ACTs need to anchor their short-term policies in strong and credible

medium-term fi scal consolidation, with the speed of adjustment depending

in part on the availability of fi nancing. Medium-term consolidation will be

needed to support confi dence, turn unsustainable debt dynamics around, and

reduce the susceptibility to shocks. The speed of adjustment will depend,

among other factors, on the size of the fi scal imbalances and the availability

of fi nancing. By way of illustration, delaying subsidy reform in the ACTs by

two years would entail a fi scal cost of $8 billion. Raising public investment

in the ACTs by 5 percent of GDP cumulatively over fi ve years would require

$24 billion in fi nancing, while signifi cantly raising growth and employment

( Figure 2.5 ). Stepped-up support from the international community, especially

on budget support, would thus help smooth the adjustment ( Chapter 6 ).

Fiscal consolidation will require signifi cant effort over the medium term.

While countries are at various stages of planning fi scal adjustment, an

illustrative scenario can shed light on the scale of the challenge: if primary

balances were to remain at their current levels, the public debt ratio would rise

by about 17 percent of GDP on average over the next fi ve years and reach

87 percent of GDP. Restoring debt to sustainable levels (assumed here, for

purposes of illustration, at around 40–60 percent of GDP) over the medium

term will require raising the primary fi scal balance by an average of 8 percent

to 10 percent of GDP. Moreover, current account defi cits and fi nancing needs

are substantial in many ACTs. For countries with low fi scal or external buffers,

delays in consolidation could heighten concerns about the sustainability of

macroeconomic policies, further eroding confi dence and impairing growth.

Even in Libya, fi scal vulnerabilities from high breakeven oil prices (highlighted

by the renewed disruptions to oil output), and insuffi cient savings to support

spending for future generations call for fi scal consolidation.

Tackling Fiscal Challenges

13

Medium-term consolidation plans need to center on lower current spending

and higher revenue mobilization. Strategic spending reorientation should

aim at eliminating generalized subsidies, undertaking comprehensive civil

service reforms, and channeling part of these savings toward enhancing the

coverage and amounts of targeted social assistance and strengthening public

investment. The successful implementation of these reforms will also depend

on improvements in key aspects of the budget process. On the revenue

side, medium-term reforms should aim at improving the tax structure, and

increasingly turn to tax and customs administration reforms, which would

not only raise revenues but also improve governance and the business

environment. These policies would improve equity, create jobs, and enhance

long-term growth prospects by boosting productivity.

The success of such fi scal strategies will depend on getting the political economy

right. Policymakers will need to gauge what reforms are possible and how best to

sequence them under diffi cult sociopolitical circumstances. Success will depend on

listening to all stakeholders’ views when formulating policy agendas, and building

the coalitions needed to implement them. To this end, the recent tax conference

in Morocco and the ongoing national tax consultation process in Tunisia have

been useful in building consensus for tax reforms. It will be important to know

who stands to lose as a result of reform—whether in certain regions or economic

sectors or along demographic or income lines. Such knowledge can help

predict opposition to proposed plans and can inform strategies to address such

opposition. A broad-based communication strategy, emphasizing that this form of

consolidation will contain the negative impact on incomes and jobs while possibly

improving income distribution, will be critical to building political consensus and

gaining the public support needed to sustain the consolidation effort.

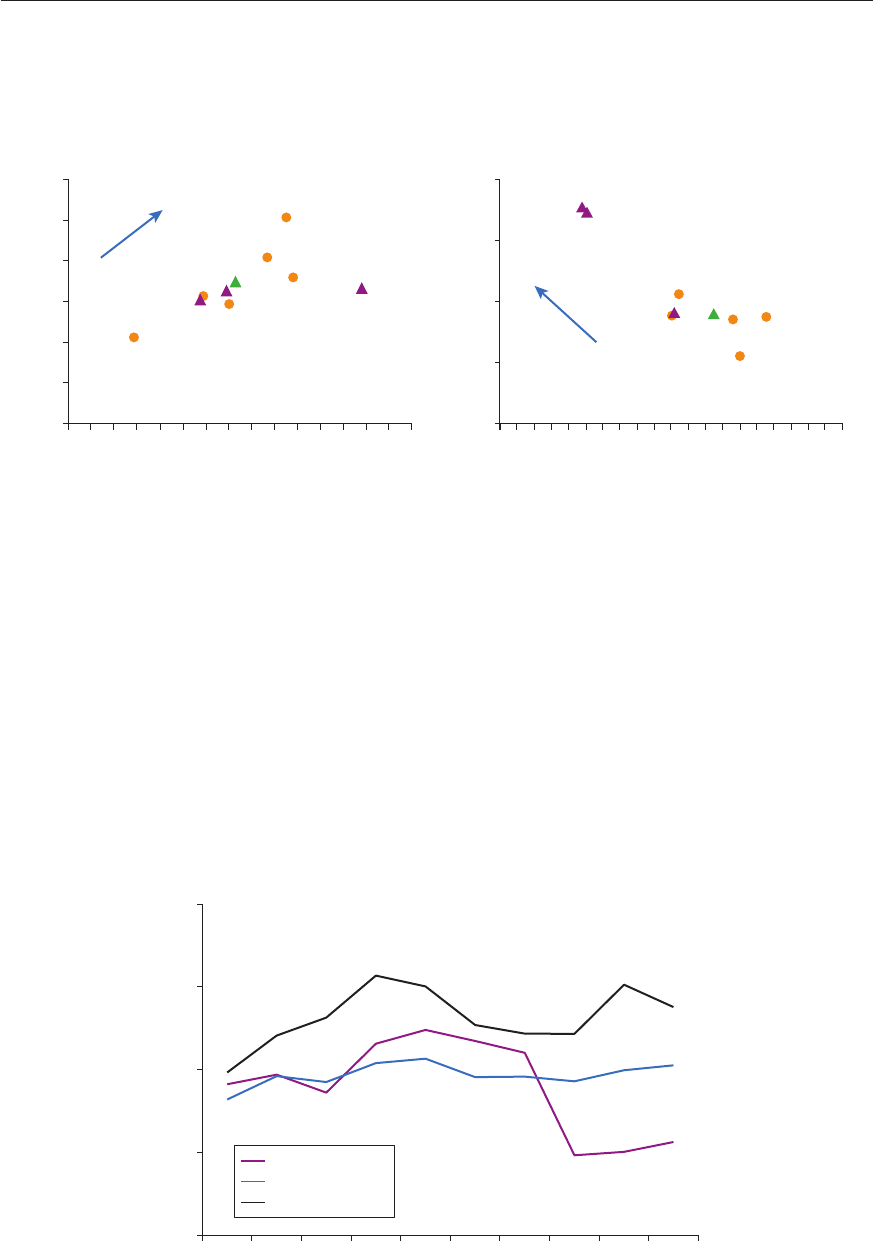

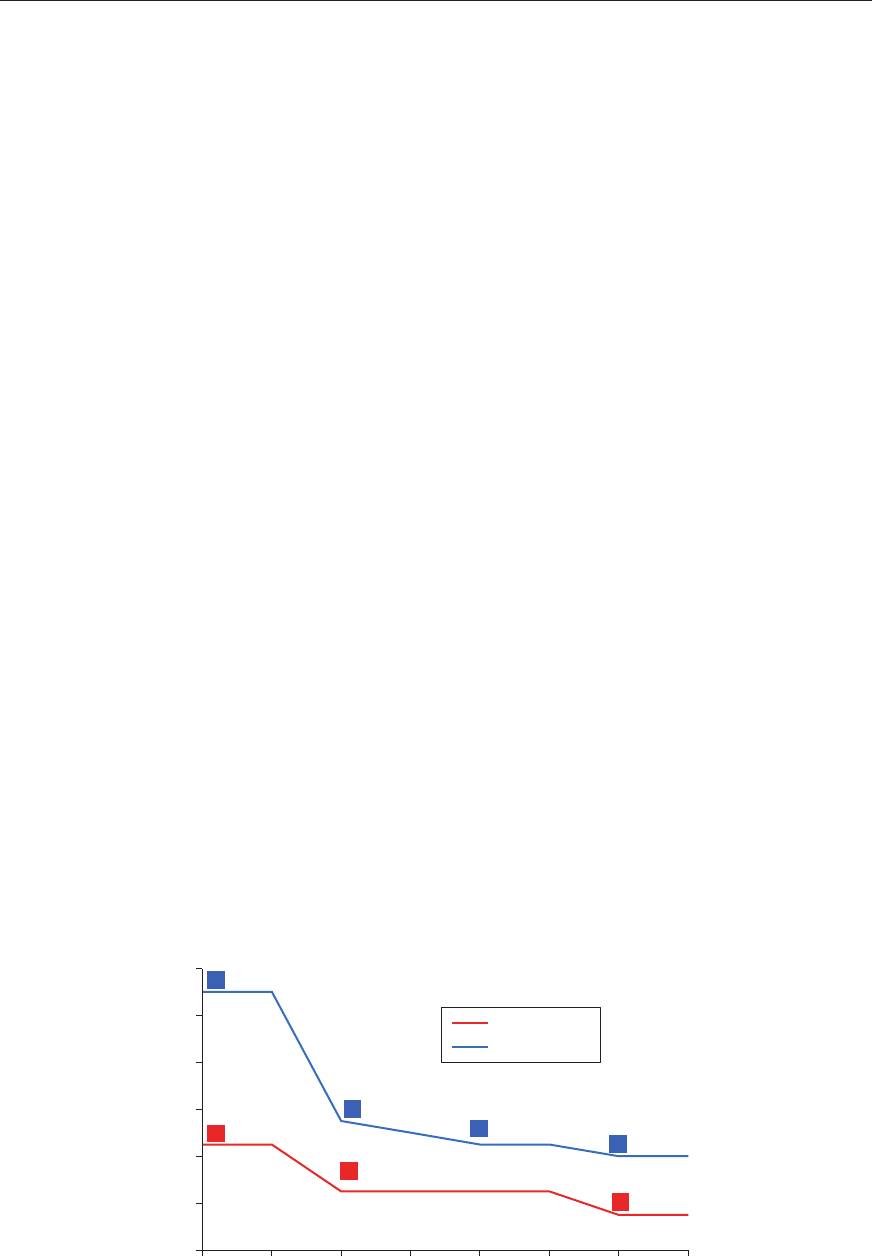

Figure 2.5. A 5 Percent of GDP Increase in Public Investment Would Significantly

Impact Growth and Employment

1

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

2008 09 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20

GDP Growth

(Percent)

5 percent

of GDP

Baseline

Projecon

0.0

0.1

0.2

0.3

0.4

0.5

0.6

0.7

0.8

0.9

1.0

2012 13 14 15 16 17

Job Creaon

2

(Million)

Source: National authorities; and IMF staff estimates.

1

ACTs, excluding Libya.

2

Under various employment elasticities.

TOWARD NEW HORIZONS

14

Reorienting Spending

Increased spending on public wage bills and generalized subsidies, in response

to social pressures, stimulated near-term economic activity, but also widened

external imbalances and worsened inequalities and expenditure rigidities.

Broad-based subsidies, especially for energy, support imports more than they

support demand for domestic goods and services, and they disproportionately

benefi t high-income segments of the population, who consume large

amounts of fuel and electricity. Consequently, the bulk of subsidy increases

was transferred to the wealthy and had limited effect in generating jobs or

improving the living standards of the average household. Hikes in public wage

bills were introduced in a diffi cult sociopolitical context; their continuation is

not a sustainable policy option ( Figure 2.6 ). They also tend to raise inequality

(IMF, 2012c), especially where government employees hold an above-average

position in the income distribution ( Figure 2.7 ). Recognizing the limitations of

cross-country comparisons in this area, among the ACTs, income inequality

is highest in Tunisia and Morocco, where average civil service wages are three

and four times per capita GDP, respectively. Expenditure rigidities stemming

from the public wage bill and generalized subsidies, both above emerging and

developing country averages, create additional challenges for fi scal policy.

Carefully reorienting public spending away from generalized subsidies

towards targeted social safety nets would support poorer households,

reduce inequalities, and free resources for priority expenditure and defi cit

reduction. Stable or declining international energy prices have created

a window of opportunity for reform of energy subsidies. Given the

delicate sociopolitical environment, cuts in subsidies should be gradual and

implemented concurrently with increased targeted social assistance (including

Figure 2.6 . High Public Wage Bills

(Employee compensation, 2012; percent of GDP)

0

5

10

15

20

LBY MAR TUN YEM EGY JOR

Emerging Market and

Developing Countries Average

Sources: National authorities; and IMF staff estimates.

Tackling Fiscal Challenges

15

5

See: IMF, 2013b for more details.

6

Automatic pricing should include price-smoothing measures to avoid potentially large fluctuations in domestic

fuel prices.

Figure 2.7 . High Public Wages Tend to Raise Inequality

DZA

ARM

AZE

DJI

EGY

GEO

IRN

IRQ

JOR

KAZ

KGZ

MRT

MAR

QAT

SDN

SYR

TJK

TUN

TKM

UZB

YEM

25

30

35

40

45

0 1020304050

GINI coefficient, latest available

Public wages (average 2007–12)

in percent of total expenditure

Public Wages and Inequality

Sources: National authorities; World Bank World

Development Indicators; and IMF staff calculations.

Egypt

Jordan

Tunisia

Morocco

Africa

Asia

Europe

Lan America

1.0

2.5

2.8

3.9

1.3

1.4

1.4

1.4

Average Public Administraon Wage

1

(Percent of per capita GDP)

Sources: National authorities; and IMF staff

calculations.

1. Annual average for 2000-08, except for Jordan,

Morocco, and Tunisia, where data are for 2009.

targeted cash transfers or vouchers) to mitigate the effects on poor and

vulnerable households (see Chapter 5 ). To that end, Jordan is gradually raising

electricity tariffs, has eliminated fuel subsidies, introduced a monthly fuel

price adjustment mechanism, and reallocated some of the savings from these

reforms to the bottom 70 percent of households via cash transfers ( going

well beyond compensation for the poor, also strengthening buy-in from the

middle class, though the eligibility criteria are being fi ne-tuned with a view to

better targeting the poor segments of the population). Energy price increases

have also been implemented in Morocco, Tunisia, and Yemen. To a lesser

extent, reforms have also begun in Egypt (IMF 2013d, Box 2.4 provides details).

Instituting energy subsidy reform is politically diffi cult, and country

experiences provide key lessons for success.

5

Important elements are a

comprehensive energy sector reform plan that includes consultation with the

main stakeholders; appropriately phased energy price increases; introduction

of automatic pricing mechanisms

6

to depoliticize energy pricing; a plan to

improve the effi ciency of state-owned enterprises and utilities to reduce

producer subsidies; targeted measures to compensate and protect the

poor and vulnerable; and an extensive communications strategy, including

TOWARD NEW HORIZONS

16

publication of the magnitude of existing subsidies and planned use of

prospective fi scal savings. Opinion polls have shown, for example, that

citizens tend to support subsidy reform if they perceive that the proceeds

are used for pro-poor, education, and health spending, and if they can be

satisfi ed that these expenditures are done in an effi cient way ( Box 2.1 ).

Box 2.1. Mixed Public Views on Cutting Energy Subsidies

ACT populations are coming to terms with the need for subsidy reform, in recognition

of rising fi scal pressures. Several ACT governments have recently taken steps toward

cutting back costly generalized subsidies, especially for energy. Generally, populations

have accepted these changes, but they do hold strong opinions on the types of subsidies

that should be cut and where the savings should be allocated. A recent poll of ACT

populations, conducted for the World Bank,

7

provides more insight into their views.

Cuts in fuel subsidies are preferred over cuts to food subsidies (Table 2.1.1). In Tunisia

40 percent of respondents favored cutting energy subsidies. The response was not

as strong in Egypt and Jordan, at 30 percent, but support for the removal of energy

subsidies was several times stronger than for removal of food subsidies. This difference

may refl ect populations’ awareness that fuel subsidies disproportionately benefi t the

wealthy. The poll results also indicate that Tunisians are least likely to oppose large-

scale subsidy reform, while 60 percent of respondents in Egypt and nearly half of

respondents in Jordan were not in favor of subsidy removal.

Distributing savings to poor households and improving social services is favored,

and can improve the public buy-in for reform. At least half the respondents in Egypt

and Tunisia specifi ed that the savings from energy subsidies should be distributed

as cash transfers to the poor and as increased spending on healthcare and education

Table 2.1.1. Subsidy Removal Preferences

(Percent of respondents)

1

Egypt Jordan Tunisia

Energy 31 28 41

Food 6 13 25

None 60 47 27

No response 3 12 7

Source: World Bank MENA Development Report, “Inclusion and

Resilience: The Way Forward for Social Safety Nets in the Middle

East and North Africa.”

1

Response to the question, “If the government had to remove

subsdies, which products would you prefer they target?”

7

A Gallup poll of 4,000 interviews with adults, aged 15 and older, was conducted in Egypt, Jordan, Lebanon,

and Tunisia during September–December 2012.

Tackling Fiscal Challenges

17

(Table 2.1.2). Notably, more than two-thirds of Tunisians and nearly 60 percent

of Egyptians who opposed any subsidy removal when originally asked indicated

subsequently that they would support removing diesel subsidies if the savings were to

be distributed to the poor and to education and healthcare spending.

8

Morocco undertook successful reforms to downsize its public sector in 2005. However, further reforms are

needed to raise the productivity of its civil service. In Yemen, the cabinet recently approved a plan to eliminate

ghost workers and double-dippers in the civil service and military and security forces.

Table 2.1.2. Preferences for Distribution of Savings from Energy Subsidies

(Percent of respondents)

1

Distribute savings to . . . Egypt Jordan Tunisia

Poorest households 32 50 38

All except wealthy households 3 19 6

All households 2 3 1

Healthcare and education as well as poorest households 57 10 50

No response 7 19 4

Source: World Bank MENA Development Report, “Inclusion and Resilience: The Way Forward for Social

Safety Nets in the Middle East and North Africa.”

1

Response to the question, “Where should the government spend the savings from energy subsidies?”

Box 2.1 (concluded)

Containing public wage bills would reduce expenditure rigidities and support

fi scal strategies for sustainability and private sector job creation. Using the

public sector as employer of fi rst and last resort is no longer an option where

fi scal buffers are running low. Moreover, in some cases infl ated public sector

salaries reduce the appeal of private sector jobs for the best workers. To

kick-start reforms and facilitate private sector growth, further public sector

hiring should be strictly limited and real wage growth should be reduced by

restraining the growth of nominal wages and allowances, and by streamlining

bonuses. Near-term consolidation efforts can be complemented by medium-

term plans for comprehensive civil service reforms that review the size and

structure (including regional and functional allocations) of the civil service

to create a skilled and effi cient government work force. This would entail

reviewing existing civil service legislation and regulations to rationalize

compensation policies, improve retention, and to create stronger performance

incentives by tightening the link between pay and performance. At the same

time, strengthening the payroll system would help eliminate ghost workers and

double-dippers, especially in Libya and Yemen.

8

TOWARD NEW HORIZONS

18

9

Empirical literature finds that education is one of the main determinants of cross-country variations in

inequality (De Gregorio and Lee, 2002; IMF, 2007; and Barro, 2008).

Increasing growth-enhancing capital expenditures will be important.

Increasing outlays on effi cient capital projects, healthcare, education, and

training—particularly for low- and middle-income households—would create

jobs and reduce inequalities

9

in the near term, while strengthening long-term

growth prospects.

The quality and effi ciency of all growth-enhancing spending will need to be

monitored, and implementation capacity strengthened ( Figure 2.8 ). Public-

private partnerships (PPPs) in a variety of areas can lessen the burden on public

budgets, but only where the political environment supports them and where

strong PPP legal frameworks and mechanisms can be established to mitigate

the risk of large contingent liabilities. Strengthened reporting and monitoring

mechanisms, as well as procurement systems, are essential for improvements

in this phase, in both government and public enterprises, and would support

a better business environment. Appropriate vetting and prioritization systems

(i.e., choosing projects that relieve infrastructure bottlenecks, complement

private investment, and enhance productivity), timely allocation of recurrent

expenditures, and ex-post evaluations and internal audits would underpin

improvements in the appraisal, selection, and project evaluation stages.

Broad public fi nancial management reforms would bolster implementation

of the plans above and instill confi dence in ACT governments’ commitment

Figure 2.8 . Large Variation in the Quality of Public Investment Management

(Public investment managment index; 0 (lowest) to 4 (highest) )

Source: Dabla-Norris and others (2011).

0

1

2

3

4

TUN JOR EGY YEM LAC EM

Europe

MCD Dev.

Asia

SS

Africa

Appraisal Score

Implementaon Score

Selecon Score

Evaluaon Score

Tackling Fiscal Challenges

19

to fi scal sustainability and good governance. Improvements are needed across

key aspects of the budget process, including, fi rst and foremost, commitment

controls and strengthened systems for budget preparation, as well as

enhancements to budget coverage and audit:

•

Better commitment controls

are essential to limit the possibility

of expenditure overruns, which is especially important for the ACTs in

light of a history of overruns and substantial near- and medium-term

consolidation needs. The fi rst step toward addressing this challenge will

be for all ACTs to move immediately toward exercising expenditure

controls at the point of expenditure commitment rather than at the

payment stage. Implementing effi cient technological platforms such

as Integrated Financial Management Information Systems (IFMIS)

will be an important part of the process of improving cash and debt

management. Allocating an appropriate level of contingency reserves

would also help governments adjust to unexpected revenue declines or

spending needs.

•

Sound budget preparation

is equally important: it enhances policy

prioritization, which is key for the ACTs, given their need to prioritize

spending in the context of limited resources. Approaches vary across

the ACTs, from top-down in Jordan and Yemen to bottom-up in Egypt.

International best practices indicate that all the ACTs would benefi t from

adopting a top-down approach that is complemented by strong ties between

macro-fi scal projections and the budget, a unifi ed budget process (that

is, full integration of recurrent and capital budgets), and a closely linked

medium-term fi scal framework. This approach should be complemented by

bottom-up performance-based budgets at the sectoral level.

•

Comprehensive budget coverage and increased transparency

are

needed to be able to adequately assess the fi scal stance and rein in extra-

budgetary spending. Budget coverage in the ACTs tends to be narrower

than in other regions (see IMF, 2013c, Box 2.5 ). Coverage that includes

public enterprises, social security and pension funds, along with broad

budget reporting that encompasses functional classifi cations, contingent

liabilities, and arrears, would enhance transparency and risk assessment.

This would rein in the use of third-party revenues and unused budget

allocations for extra-budgetary expenditures, support the tracking of

poverty-reducing expenditures, and facilitate the analysis of the allocation

of resources across sectors. A statement of fi scal risks as part of the

budget documents would also strengthen transparency. Disclosure of

budget documents and outcomes would help strengthen accountability.

•

Strong internal and external audit procedures

are essential to

implementing fi nancial controls and risk management, thereby

TOWARD NEW HORIZONS

20

strengthening governance. Morocco has made good progress in this

area, but there is ample scope for strengthening such procedures in other

ACTs. International best practices indicate that the ACTs should strive

for independent auditors with clearly defi ned functional and institutional

roles, suffi cient access to information, and the power to report to the

appropriate authorities.

For ACTs that have embarked on decentralization, potential fi scal risks

should be limited with a sound intergovernmental fi scal relations framework.

Efforts in most ACTs to embark on decentralization pre-date the political

transitions that started in 2011, though decentralization endeavors are now

infl uenced and shaped in part by the transitions. Except for Morocco, the

ACTs are still in the early stages of decentralization ( Box 2.2 ). Before moving

forward, it will be important for these countries to strengthen their public

fi nancial management along the lines suggested above: clarify expenditure

assignments, transfer and equalization systems, and build capacity at the

level of sub-national governments. This includes appropriate sequencing

of resources across sub-national governments (e.g., ex ante defi nition of

the resource envelope for sub-nationals) in line with the assignment of

spending responsibilities and limits on sub-national borrowing to avoid

excessive borrowing and ensure fi scal discipline. The pace of decentralization

should depend on the capacity of sub-national governments to carry out

their assigned functions, which in turn relies on the strength of their public

fi nancial management. Finally, development of effective intergovernmental

transfer systems should offset vertical and horizontal imbalances across

various levels of government.

Mobilizing Revenues

Weak tax structures in many ACTs limit tax revenues and foster inequalities.

In these cases, revenues have persistently suffered from weak collection,

largely the result of high tax exemptions and compliance issues, and, in some

countries, low income and corporate tax rates compared to those in other

emerging and developing countries. The tax effort is generally well below

100 percent in the ACTs (except Morocco), implying that the gap between

actual and potential tax revenue collection is substantial ( Table 2.1 ).

10

This

fi nding is robust to various measures of potential revenue: these include

comparing a country’s tax receipts with: (i) the average of its peers, controlling

10

The tax effort is measured as actual tax collection in percent of potential tax revenues, estimated by

comparing a country’s tax receipts with those of peers with similar characteristics.

Tackling Fiscal Challenges

21

Box 2.2. Progress on Decentralization

Jordan is in the initial stages of decentralization. A draft Local Councils

Law, focused on administrative reforms, was prepared in 2010, but budgetary

and financial management aspects of the law are relatively limited. Several

parameters of reform have yet to be clarified: the link between governorates’

and national priorities; mechanisms for deciding the allocation of resources to

each governorate; the link between capital projects in the governorates and the

recurrent expenditures needed to operate the projects (on line ministry budgets);

and the link between new policies and governorates’ development of financial

management capacity.

In Morocco, regions already have some autonomy while also receiving transfers

from the central government; however, resource distribution across regions involves

a cumbersome process that generates regional disparities. In January 2010, to address

these challenges, the King appointed the Consultative Commission for Regionalization

(CCR), an advisory committee, to prepare a roadmap for a new model of

decentralization. The CCR proposed a number of important reforms that are currently

under discussion. Some key elements of the reforms include enhancing governance at

the regional level, strengthening regional involvement in implementing development

projects, and improving capacity at the sub-national level by transferring competencies

from the central government to local councils.

Tunisia is moving toward decentralization; key principles have been enshrined in

the recently approved constitution. Progress in decentralization so far has been slow:

there have been no major changes in expenditure assignments; governorates continue

to exercise tight control of municipalities; and governors (executive heads of the

governorates, appointed by the President) are still reporting to the Ministry of the

Interior. Devolution of public services is more advanced: in the education, health,

and agricultural sectors, a growing share of the budget is implemented by legally

autonomous entities (Etablissements Publics Administratifs). Nevertheless, their operational

autonomy for personnel management and procurement can still be increased.

In Yemen, the Ministry of Local Administration (MOLA) paved the way for

decentralization with amendments to the Decentralization Act and the Decentralization

Strategy; however, progress has been held back by capacity constraints at the

governorates and slow implementation of important public fi nancial management

reforms. The shape of future federal arrangements, including those related to

decentralization issues, is currently under discussion.

for a range of characteristics likely to affect the ability to raise revenue, such

as per capita income (see regression analysis in Box 2.3 ); or (ii) the maximum

that others with similar characteristics have achieved (stochastic frontier

TOWARD NEW HORIZONS

22

Table 2.1 . Room for Improvement in Tax Effort and VAT Collection Efficiency

1

Tax Effort

1

VAT Collection Efficiency

3

Regression Analysis, Box

2

Stochastic Frontier Analysis

2

Jordan 51 64 74

Egypt 73 72 . . .

Morocco 95 93 72

Tunisia 91 . . . 53

Yemen . . . 73 . . .

Sources: National authorities; IMF 2013c; and IMF staff estimates.

1

2012.

2

Based on IMF 2013c, Appendix 2.

3

Average for emerging markets with most comparable characteristics to the ACTs.

Figure 2.9 . Scope for Additional Revenue Collection

(Tax rates and revenue, 2012

1

)

Sources: National authorities; KPMG; Deloitte; and IMF staff calculations.

1

Or latest available data.

Goods and Services

Income

Trade

Other

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

35

40

45

MAR TUN EGY YEM JOR LBY

Top Tier Personal Income Tax Rates

(Percent)

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

35

40

45

MAR TUN EGY YEM LBY JOR

Top Tier Corporate Income Tax Rates

(Percent)

0

20

40

60

80

100

120

JOR MAR EGY YEM TUN LBY EMDC

EMDC Average EMDC Average

Tax Revenue Components

(Percent of Total Revenue)

Tackling Fiscal Challenges

23

analysis). Similarly, the ACTs’ value-added (VAT) collection effi ciency is low

relative to the 80 percent average of emerging and developing economies.

Tax progressivity is also low in most ACTs. In the non-oil ACTs the lack of

progressivity largely refl ects reliance on goods and services taxes and limited

progressive income taxation. Absent change in the tax structure, these revenue

challenges are expected to persist in the medium term in Egypt, Jordan, and

Tunisia. In Yemen and Libya, the risk of declining oil prices underlines the

importance of developing their non-oil sectors to create jobs, diversify growth,

and develop a tax base that can supplement oil-related income over time.

Raising additional revenue is a priority for the ACTs ( Figure 2.9 ). Low tax

revenue intake suggests the potential for additional collection, while revenue

multipliers that are smaller than the multipliers on the expenditure side

imply that revenue generation is a less costly means—in terms of growth

impact—of providing additional fi scal space than expenditure cuts. Collecting

additional revenue can thus generate fi scal resources for priority expenditure

and defi cit reduction, without a high cost in growth and jobs.

Revenue gap analysis suggests country-specifi c areas where revenue measures can

raise yields and support growth, equity, and competitiveness. Revenue gap analysis

is applied to guide the focus of efforts to improve tax yields ( Box 2.3 ). Egypt and

Tunisia, in particular, have scope for measures that would improve yields from

consumption taxes, the main area in which they fall short of their tax potential.

Jordan could substantially raise its revenue potential by focusing on income tax

collection; a draft income tax law, aiming to increase rates for individuals and

corporates, was submitted to Parliament in February 2014. Even Morocco,

with tax revenues close to potential, would benefi t from greater effi ciency in tax

collection. To reduce their reliance on oil revenues, Yemen and Libya need to

build their non-oil revenues across consumption, income, and other taxes. Some

key initial tax policy measures that will help the ACTs raise revenues while meeting

other macroeconomic and equity considerations include broadening the tax base,

introducing greater income tax progressivity, and raising excise and property tax rates.

Broadening the tax base promotes several macroeconomic and equity objectives.

It fosters equity, especially compared to across-the-board rate increases which can

be both regressive (particularly for income and consumption taxes) and politically

challenging to implement. New evidence confi rms that base broadening is also

better for growth—especially for VAT (Acosta-Ormachea and Yoo, 2013)—and

for improving the business environment. Consequently, tax exemptions and

deductions (except those protecting the poor) should be heavily reduced for all

taxes and, whenever possible, multiple VAT rates consolidated into a single rate

while raising registration thresholds ( Table 2.2 ). Some progress has been made

with the introduction of taxes on large agricultural fi rms in Morocco and moves

toward harmonization of onshore and offshore taxation in Tunisia (including a

reduction of the onshore income tax rate). More broadly, reducing tax exemptions

would also reduce tax administration and compliance costs as well as tax evasion.

TOWARD NEW HORIZONS

24

Box 2.3. Tax Potential and Revenue Gaps in Non-Oil ACTs

Revenue gaps, the difference between actual tax revenues and estimates of

their potential, highlight areas where ACTs can garner further tax revenues.

In any country, tax potential depends on characteristics that are likely to affect its

revenue-raising ability—economic (such as its level of development, or revenue from

other sources), political (including constitutional), and even geographical (revenues

can be harder to raise when borders are long and porous). Consequently, tax potential

can be estimated by comparing a country’s tax receipts with the average of its peers,

controlling for economic characteristics (Table 2.3.1). By construction, some countries

will have revenue above this average, and others will have revenue below. Libya and

Yemen are excluded from the analysis because they rely mainly on oil revenues.

The domestic tax potential of non-oil ACTs varies greatly.

11

Applying a novel

dataset of 66 middle-income and emerging economies from Torres (2014), tax potential

is assessed separately for consumption and for other taxes. Controlling for differences in

per capita gross national income, VAT or GST rates, top tier corporate income tax rate,

the redistribution of tax revenues (proxied by social spending and direct subsidies),

12

and the current business cycle position (proxied by the gap between the current GDP

growth rate and its potential), the following fi ndings emerge (Figure 2.3.1):

Table 2.3.1. Determinants of Tax Revenues

(Percent of GDP)

Total domestic tax Consumption tax

1

Per capita GNI 1.75*** 0.82***

VAT rate 0.33* 0.21*

Corporate Income tax rate

0.04

. . .

Social spending 0.70*** 0.22***

Growth gap 0.51*** 0.19*

Constant 8.75** 3.85***

Number of countries 64 66

Adjusted R-squared 0.69 0.42

***, **, *: statistically significant at 1, 5, and 10 percent.

Sources: National authorities; and IMF staff estimates.

1

Includes VAT and excises.

11

Because international trade taxes have experienced a declining trend in the ACTs with the lowering of

international trade barriers, this analysis focuses on domestic taxes—defined as the total collection of taxes less

international trade taxes.

12

Per capita gross national income is highly correlated with the VAT, corporate income tax rates, and social

spending. Consequently, the regression applies these variables after they have been purged of their correlation

with per capita gross national income.

Tackling Fiscal Challenges

25